“I never intended to conduct in public.” This was the candid confession that, in April 1980, John Williams disclosed in one of his first interviews as newly appointed Principal Conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra (Pfeifer 1980). At the time, the Boston Pops—the “light symphonic music” branch of the Boston Symphony Orchestra—was one of the oldest musical ensembles in the US and the first of its kind, having as a mission the popularisation of the symphonic concert-going experience. It was also the most visible, with an intense and best-selling presence in the record market, radio waves, and TV screens—with the regular show Evening at Pops having been aired continuously since 1969, it made the Boston Pops arguably the only orchestra with such wide-audience fame at that time. The confession from the newly appointed conductor about him having never thought about a career as a concert conductor seems rather puzzling and paradoxical. Taking the move from this apparent paradox, in this article I reflect on the importance of John Williams’s other career, as a conductor, building on and reframing my previous research on the topic (Audissino 2012, 2021a, and 2016).

A serendipitous start

In the summer of 1979, the Boston Pops Orchestra was in crisis mode. Arthur Fiedler, the orchestra’s Principal Conductor and, in a way, the second founder of the orchestra, had just died, after a trailblazing tenure of fifty years. The Boston Pops had been created by Henry Lee Higginson in 1885 but it was with the start of Fiedler’s “reign” in 1929 that the ensemble acquired their name, as an entity separate from the mother-orchestra Boston Symphony. It gradually expanded their reputation, to become the widely known “America’s Orchestra” they had become by Fiedler’s death (on the Boston Pops, see Adler 2023). Replacing Arthur Fiedler was a major life-or-death decision for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s management, as the very future of the orchestra was at stake. After a year-long selection process—already set in motion when Fiedler’s health had dramatically declined—amongst the five shortlisted finalists, John Williams was offered the job. Fiedler was a “classical” musician with a penchant for show-business theatrics—famous are the covers of his LP albums, in which he posed in glamorous pictures or in parodies of pop culture icons, for example, his Tony Manero impersonation for his final album Saturday Night Fiedler (Midsong International, MSI 011, 1979). After this flamboyant leader, the BSO management offered the job to an introverted and professorial-looking composer with admittedly no experience in concert conducting. And a film composer—from Hollywood. Williams’s appointment left some people in the business a bit perplexed, on the grounds of his limited experience as a conductor, as well as for inveterate prejudices against film composers, which were still rampant at the time (Audissino 2021a, 4–9), influenced by such Adornian postulates as “no serious composer writes for the motion pictures for any other reason than money” (Adorno and Eisler 2007, 37).

What led to Williams’s appointment as Fiedler’s successor can be examined from two sides: the BSO’s and Williams’s. As to the former, the decision was the result of various factors. Though very different from the Fiedler persona, Williams had strong connections not only in the records market but also in the film and television markets, thus making him able to guarantee the continuation of the Pops’ media visibility. Williams was also attractive for his skills as an arranger, and the Boston Pops is an orchestra that needed to produce new arrangements each season. Williams’s classical conservatory training also made him a tasteful arranger suitable for the symphonic medium—a much sought-after change after Fiedler’s last period, which many observers deemed to have been plagued by “trashy arrangements” (Dyer 1980a) and treatments of music that would make the orchestra players frustrated if not irate (Audissino 2021a, 30). This last point is an important one, given the balance that the Boston Pops—in its programmes that mixed staples from the concert repertoire and symphonic arrangements from the more popular and mass-audience repertoires—was being called to maintain. This balance was always liable to be a precarious one, oscillating between the categories of the so-called “high-brow” (the “art-music” symphonic repertoire) and the “low-brow” (popular music). The Boston Pops has been indeed indicated as an example of “middle-brow” (Adler 2017), those cultural institutions or operations that aim at mediating between the two opposite poles. In its history, the Boston Pops has seen moments where this balance has tipped, in either direction. During Alfredo Casella’s tenure (1927–1929), he would programme too many pieces from the “art-music” repertoire, including some new modernistic music, to the dissatisfaction of the audience members (Audissino 2021a, 18). Fiedler was brought in to rebalance the programming towards the “low-brow” side, bringing in Tin Pan Alley tunes and Broadway musicals in the mix. Yet, in his last decade, Fiedler had perhaps ventured too far in the opposite direction, dishing out symphonic arrangements of the Bee Gees songs (Clip 1) or programming disco-music versions of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (Clip 2)—in this case, to the dissatisfaction (and outrage) of the orchestra members. Williams could once again rebalance the Pops’ programming with more “high-brow” traits. This latter aspect was reflected in the orchestra’s evaluation questionnaires, one important assessment tool that the selecting committee had used to select the new conductor. After their performance, each guest conductor in the 1979 season was ranked by the orchestra according to their responses to a battery of questions, relating to the technical hard skills as well as their individual characteristic soft skills. Williams was ranked first by the orchestra members in such questionnaires (Audissino 2021a, 22). Particularly appreciated were his efficient professionalism (honed by years of experience of the “time-is-money” pressure typical of studio recording sessions), his straight-to-the-point no-nonsense attitude (some concert conductors are raconteurs prone to “waste” rehearsal time with aesthetic or philosophical musings), and his musical taste (at the time, Williams had just single-handedly brought back the symphonic sound to film screens, with Star Wars becoming the best-selling album of symphonic music). All these aspects led to the apparently least experienced of the candidates to be appointed to succeed what, at the time, was perhaps the most popular orchestra conductor in the US. The paradox, though, can be dissipated when all the above criteria are considered. What ensured continuity, though, was the one thing that Williams and Fiedler did have in common: the commitment to bringing the sound of a symphony orchestra to the masses, Williams with his film compositions, Fiedler with his concerts.

From Williams’s side, landing the Boston Pops job—“greatest honor in the profession” (Dyer 1980b)—looks perfectly suited to be called “serendipitous,” the quality of “finding valuable or agreeable things not sought for” (Merriam-Webster). Here we can better understand his apparently paradoxical, and to some perhaps alarming, statement “I never intended to conduct in public.” Though lacking the initial intention, Williams soon demonstrated that he did have the required skills and stage presence to follow in Fiedler’s footsteps: in his very first 1980 season he soon moved from “I never intended to conduct in public” to conducting in front of an audience totalling more than one hundred thousand at the Fourth of July outdoor concert at Boston’s Hatch Shell. Though limited, Williams’s experience as a conductor was not negligible. He had been conducting the recording sessions of his own scores since at least the mid-1960s—“out of self defense” in order to protect his musical ideas from uncaring studio conductors, he explained (Dyer 1980c)—and though such sessions lacked the typical elements of live concerts, at the time of the Pops appointment he had already matured a fifteen-year experience in how to lead an orchestra, and at least a few public appearances.

The debut in public conducting, as far as I know, took place with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on Saturday, October 30, 1976, in London at the 7th edition of the FilmHarmonic “Festival of Film and T.V. Music,” at the Royal Albert Hall.1 Williams presented a programme of his own film music as well as a selection of Bernard Herrmann’s, as the composer had passed away the previous December:

-

The Cowboys (Mark Rydell, 1972), arguably what is now known as “The Cowboy Overture.”

-

A Suite called “The Romantic Themes” that included music from Heidi (Delbert Mann, 1968); The Paper Chase (James Bridges, 1973), with a solo piano listed in the programme; The Eiger Sanction (Clint Eastwood, 1975), with a solo trumpet listed in the programme; “Dream Away” from The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing (Richard C. Sarafian, 1973), with a solo mouth organ listed in the programme; Cinderella Liberty (Mark Rydell, 1973); “Make Me Rainbow” from Fitzwilly Strikes Back [sic] (Delbert Mann, 1967); The Reivers (Mark Rydell, 1969); Jane Eyre (Delbert Mann, 1970).

-

“A Tribute to the Music of Bernard Herrmann,” including “The Death Hunt” from On Dangerous Ground (Nicholas Ray and Ida Lupino, 1951) and a selection from Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941).

-

The “Overture” and “Cadenza and Variations for Violin” from Fiddler on the Roof (Norman Jewison, 1971), Williams’s own cinematic adaptation of the Jerry Bock musical, for which Williams had won the 1971 Oscar for Best Musical Direction and Adaptation.

-

“Suite – The Disasters,” devoted to excerpts from the Williams scores to such “disaster movies” as The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 1972); The Towering Inferno (John Guillermin, 1974); Earthquake (Mark Robson, 1974); Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975).

The programme is of additional interest because it shows the pre-Star Wars John Williams, the film having been a massive watershed that changed Williams’s status radically. Interestingly, the film is passingly mentioned in the programme notes of this concert, before anyone could fathom the degree of importance it would have in the history of film music: “At present he is working on a new British-made film, Star Wars.”2

This Albert Hall appearance was an exception, and in some mail correspondence afterwards he confirmed that concert-conducting was not his job: “I don’t concertize, it’s just not part of what I do professionally, whereas Mancini and Elmer Bernstein and Michel Legrand and some of these other chaps do that as a way of earning money” (Caps 1982, 4). Yet, after Star Wars (then retitled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, George Lucas, 1977) invitations to guest conduct increased in number. Ernest Fleischmann, General Manager of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, asked Williams to compile a suite from the film score for space-themed concerts at the historic Hollywood Bowl, a spacious outdoor concert venue on the Hollywood hills. Williams the composer obliged, but Williams the conductor was not ready to step onto the podium: “I just said to Ernest, ‘You have one of the world’s great conductors in Zubin Mehta. It would be better if he did it, and I’ll come as a guest’” (Burlingame 1998). Mehta, then Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, did the honours, on November 20, 1977, in front of a sold-out 17 000-seat venue. Fleischmann, undaunted, kept offering guest conducting gigs to Williams, who kept politely declining the invitations (Burlingame 1998). In the meantime, on March 26, 1978, Williams appeared as a guest—alongside the revered veteran Miklós Rózsa—on the TV show Previn and the Pittsburgh (Clips 3 and 4) on PBS (the US Public Broadcasting Service), in an episode entirely devoted to film music, where the Music Director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn, also “conducted” conversations with Williams and Rózsa. On the show, Williams conducted the “March from Superman” (from the film Superman: The Movie, Richard Donner, 1978), a suite from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977)—similar to the Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind currently distributed in print by Hal Leonard—and two pieces from Star Wars (“Princess Leia” and “Throne Room and Finale”). In the summer of the same year, Williams finally gave in to Fleischmann’s courting and accepted to cover as a last-minute replacement in a couple of Hollywood Bowl concerts: “So finally in ‘78 I went in and conducted a weekend, or possibly two. […] Ernest called me to do those concerts […] mostly, I thought, because all of the practicing conductors would have been booked during the busy summer season. I was working in the studios, and he assumed, rightly, that I would have been free on those weekends” (Burlingame 1998). The conductor who had to be replaced at the very last moment was Arthur Fiedler himself. Williams further reminisces, “Then he wanted to have me there [at the Hollywood Bowl] every year; so, really, without Fleischmann I don’t think I would have ever stepped in front of the public to conduct. I certainly never had any intention of doing so” (Beek 2021). The Hollywood Bowl debut on July 28, 1978 marked for Williams both the beginning of forty-five years of regular appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic—the most recent was in July 2023, Williams being 91 years old—and the beginning of the similarly long association between Williams and the Boston Symphony Orchestra family—at the time of writing, Williams still holds the title of Boston Pops Laureate Conductor.

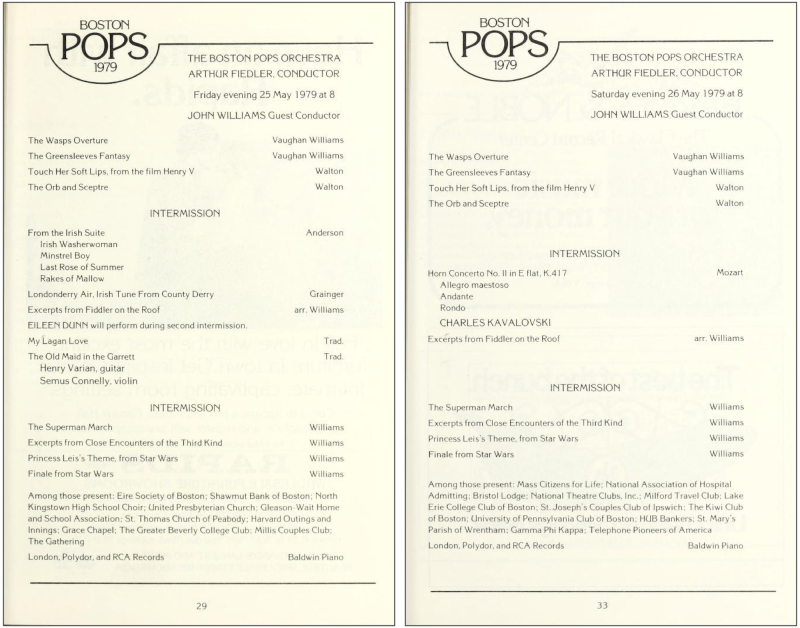

As an effect of the combination of the Star Wars success, his TV appearance with the Pittsburgh Symphony, and his “Pops at the Bowl” weekend of concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the following year Williams was invited to guest conduct the Boston Pops at Boston’s Symphony Hall, in two concerts on May 25 and 26 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Concert programs from the Boston Pops Orchestra, May 25 and 26, 1978.

Boston Pops. May–July 1979. Arthur Fiedler Conductor. Boston: Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1979, 29 and 33.

Those appearances demonstrated the solid symphonic substance of his film compositions, the tastefulness and musical inventiveness of his arranger’s skills, and his good handling of the concert repertoire as a conductor (Mozart, Vaughan Williams, and Walton were the “higher-brow” elements in the programme).3 The guest appearances, as we have seen, happened to take place in the year in which Fiedler’s successor was being recruited—the ailing Pops conductor would die on July 11, 1979—and Williams thus found himself amongst the “papable” names: at the time of the search, the election of the new Pops conductor was comparatively given in Boston the same gravitas as the pontifical election in Rome (Swan et al. 1980, 85). Williams accepted the job on January 9, 1980 and the announcement was given at a press conference in London, where Williams was currently recording the score to Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980).

BSO Manager Tom Morris came to London […] and asked me if I’d like to be the director of the Boston Pops. It was the most flattering thing one could think of—to be offered the directorship of an American institution as venerable, prominent, and successful as the Pops. So, naturally, I found it hard to resist, though I didn’t agree immediately. I told Morris that I had very little experience conducting in public. He said, “I think you can do it, and André Previn has convinced us you can do it, and the players committee has elected you as the person of their choice.” So I promised to think about it. I spoke to my wife and my friends, to André Previn, and they all said, “You really should do this. It’s a very important thing because, although it couldn’t be more different than Hollywood, it’s bound to enrich your life.” So with some trepidation and a lot of excitement, I rang him up and said, “I’ll try it.” (Burlingame 2000, 20)

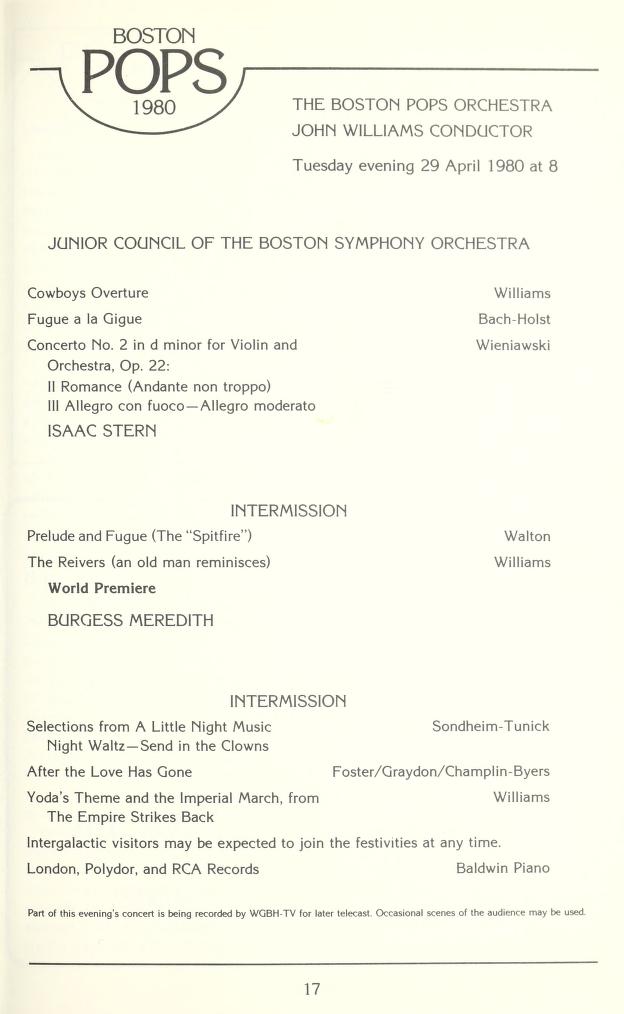

His debut concert as newly-appointed Pops conductor was at New York’s Carnegie Hall, for a special concert on January 22: the programme included Williams’s “Cowboys Overture,” Gabriel Fauré’s Pavane, Op. 50, Camille Saint-Saëns’s Concerto No. 3 in B minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 61, a selection from the musical Gigi (music by Frederick Loewe), and four Williams pieces, “Superman March,” Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, “Princess Leia” and “Finale [Throne Room and Finale]” from Star Wars. The debut in the orchestra’s home-town took place on April 29, 1980 (Figure 2)—in front of the cameras taping the first Williams episode of Evening at Pops. Besides featuring world-renowned violinist Isaac Stern performing the Concerto no. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 by Henryk Wieniawski, it should be remembered as the world premiere of “The Imperial March,” the concert version of Williams’s “Darth Vader’s Theme” from Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back. Williams, the reluctant conductor, thus reminisced about his arrival in Boston:

I knew that he [Arthur Fiedler] had built and maintained an extraordinary musical institution, but I had no conception of the enormity of what he did until I was invited to conduct in Boston. When I arrived there, I learned that the Pops played not two times each week, as I had thought, but performed six concerts a week, each week, for the duration of the Pops season. Considering that Arthur Fiedler maintained this pace for fifty seasons, this is a staggering achievement. […] One was instantly aware that this was a man of extraordinary energy, who possessed a breadth of knowledge in the field of light music repertoire that was unique. And his success was truly unique. As far as I know, he was the only person in the history of music who held a major conducting post for fifty years. Not even Johann Strauss, the waltz king, in his great days in Vienna, could have claimed to have had a greater success with his concerts, both musically and as a social event, than Arthur Fiedler had in Boston. […] Bearing all of this in mind, you can imagine the trepidation with which I arrived in Boston to start my first series of concerts as successor to this great man. I was the “new boy in town,” being scrutinized by Arthur Fiedler’s loving audience. I needn’t have worried—everyone, the orchestra, management, and the Boston public made me feel instantly welcome. One could immediately sense the overriding sentiment of all present. There was an undying affection for the institution that he served so well and so long. Added to this were the wishes of everyone for the brightest possible future of the Pops. (Williams 1981, 172–173)

Figure 2

Concert program from the Boston Pops Orchestra, April 29, 1978.

Boston Pops. May–July 1980. John Williams Conductor. Boston: Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1980, 17.

Williams’s successor, Keith Lockhart, acutely noted an aspect that should be taken into consideration when considering John Williams’s appointment at the Pops:

For John this job must have been a huge challenge and a huge responsibility, because parts of this job that I [as a trained conductor] don’t have to think about are the symphonic warhorses. When we have violinists coming and they’re doing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, or pianists coming and they’re doing the last movement of the “Rach 2”, this is my bread and butter, this is the stuff I have been studying since I was twenty-one. By the time I came here I had fifteen years of that sort of work under my belt. The reason I can concentrate on all the new things, the commissions and things like that, is because I already know all that standard repertoire. But imagine if that stuff had been new to learn, which was the case with John! All John had conducted was his own work in the studio, basically. Like a lot of the studio composers, he conducted his own recording sessions. But it’s a different thing when you have to start interpreting everybody else’s work too. So, my hat’s off to him. I’m sure he was a very busy boy! And at the same time composing film scores… (Audissino and Lehman 2018, 407–408)

Being appointed Principal Conductor not only entailed conducting the majority of the concerts and designing the season’s programmes, but also setting the agenda, artistic policies, and objectives for the longer term. In the first press conferences, Williams tackled his plans for the Pops. The first point was the renewal of the repertoire:

The most noticeable changes will be in the third part; we’ve got to try to update the Pops library to add some new pieces. […] The first part of the program, too, will see some changes. In May we will be playing more than 60 numbers in the first part of the evening, and of them approximately 35 percent are things the orchestra hasn’t seen before, at least in this context. That’s good, I think: it keeps the interest of the players up, piques the interest of the audience. (Dyer 1980c)

In Williams’s debut season, one third of the circa sixty pieces presented consisted of new material that had never been performed by the Pops before (Pfeifer 1980). As regards the “trashy arrangements” of rock and disco music, Williams clearly sided against those:

There are some things that shouldn’t be tried. A symphony orchestra is never going to swing the way a jazz band does, it is never going to rock the way a rock band does. In arranging music for the Pops it is important not to ask musicians to do something they shouldn’t do, and that they cannot do. (Dyer 1980c)

Another goal was the recovery of the “Great American Songbook”:

Some of our greatest composers were songwriters who were not orchestrators in the way that the great classical composers were. Their work has come to us through the work of an outside orchestrator. Some of these composers were very lucky: I think of Richard Rodgers, who had Robert Russell Bennett working for him throughout most of his career. […] But most of our songwriters were not as lucky as that, and most of their work is in very poor shape. Gershwin is in pretty good shape, because Ferde Grofé was around, but most of the work of his contemporaries is in unspeakable condition. In the period between the First World War and about 1950 there was an explosion of creativity, but there are no definitive orchestral versions of the work of Porter, of Irving Berlin, of Harold Arlen, […] of Harry Warren, of Jimmy McHugh, of Jerome Kern, who may have been the greatest of them all. One of the things I would like to see done for future generations not only of Americans but of everyone would be to have this treasure of ours put into shape for orchestra. […] The Pops is supposed to be the custodian of American popular music, and this is part of its job. (Dyer 1980c)

Finally, film music could be an essential ingredient of these innovations that Williams wanted to bring in:

It is possible that I can bring prestige to the best film music by presenting it in a concert format. Only one half of one percent of the music written in the 19th century is anything we ever hear today; surely there must be at least that percentage of good music written for films. (Dyer 1980d)

Fiedler had already programmed film music, and in order to give film music a better recognition, the mere presence of this repertoire in the concert programmes was not enough. The key operation was to increase the qualitative consideration of film music, not so much the quantitative presence. The original format of the Boston Pops programmes, discontinued in 2010, used to be a tripartite one. The first section was devoted to a selection of the “war horses” from the symphonic repertoire: opera overtures, selections from ballets, single movements of famous symphonies—Fiedler’s favourites were Gioachino Rossini’s Overture to William Tell, Franz von Suppe’s “Light Cavalry Overture,” or Aram Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance” from the Gayane ballet suite.4 After an intermission, the second section would have a soloist in the spotlight, either from the “classical” or the “popular” arenas—examples are the pianist Earl Wild playing George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue or Ella Fitzgerald singing selections from Broadway showtunes. After another intermission, the closing section would provide the audience with the lighter treats in the programmes, what Fiedler called “gumdrops” (AAVV 2000, 36), in the form of symphonic arrangements of the most popular tunes, or symphonic marches, or humorous symphonic miniatures. It was in this third section that film music would be accommodated, and Fiedler used to choose film music in a pop language, something akin to the pop-song repertoire.

A survey of the list of film-music pieces programmed by Fiedler during his tenure (Audissino 2016, 149–151) reveals the criteria at the base of his selections. Fiedler would choose new releases that had been hits in the easy-listening record charts—for example, “Lara’s Theme” from Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965, music by Maurice Jarre), the theme from Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970, music by Francis Lai), “Gonna Fly Now” from Rocky (John G. Avildsen, 1976, music by Bill Conti), the sirtaki from Zorba the Greek (Michael Cacoyannis, 1964, music by Mikis Theodorakis)—or songs that had been featured in prominent recent films—“Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head” from Butch Cassidy (George Roy Hill, 1969, music by Burt Bacharach), for example. Fiedler did not consider film music as a potential new source to renovate the symphonic repertoire in the first part of the programmes—the Overture to Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939, music by Max Steiner) instead of Rossini’s Overture to The Barber of Seville, for example—but as a type of popular music akin to showtunes. Williams’s innovative approach to the film-music repertoire consisted in a different qualitative consideration of film music. Since the performing medium was a symphony orchestra, Williams would choose film music written in a symphonic idiom and treat it as “classical music,” with the same philological respect due to any other symphonic piece. Fiedler, on the contrary, when featuring symphonic film music that had reached the hit status in the charts, would commission arrangements to make it sound “pop.” Examples include the “Main Title” from Exodus (Otto Preminger, 1960, music by Ernest Gold), which in the Fiedler version (Clip 5) sounds more “pop” than Gold’s original version (Clip 6), or the Jack Mason’s medley from Fiddler on the Roof (Clip 7) from the Fiedler era compared to Williams’s own “Excerpts for Violin and Orchestra” (Clip 8). Despite the wide availability of the original score for concert performances (Wessel 1983), Fiedler also had the “Main Title” from Star Wars turned into a less symphonic work, and a comparison between Williams’s original (Clip 9) and Newton Wayland and Richard Hayman’s arrangement, retitled “Theme and Dance from Star Wars” (Clip 10), is enlightening as to the widely divergent consideration that the two conductors had for film music.5

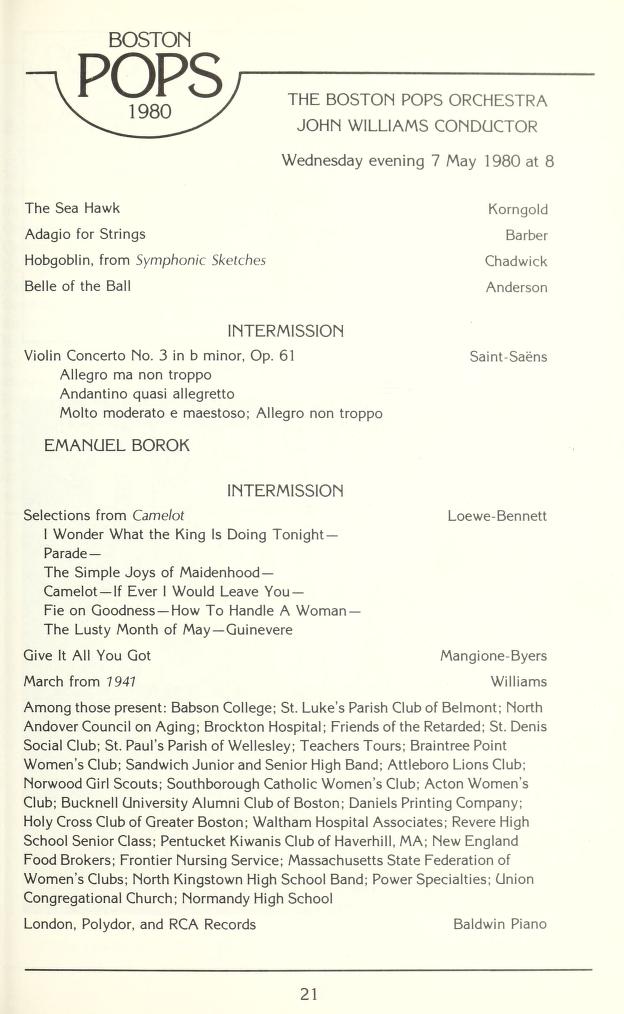

Williams also broke barriers in the concert programmes. The tripartite format used to relegate film music in the third part (the “pop” hits), while Williams began to include film-music pieces in the first part too, traditionally reserved for art-music classics popular with the wider audience. In one of his first concerts as the new Pops conductor (May 7, 1980; Figure 3), Williams opened the programme with Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s overture from the film The Sea Hawk (Michael Curtiz, 1940), an honour position usually reserved for traditional overtures from operas. I have already mentioned Williams’s attention for philological presentations and his commissions of faithful reconstruction in case the originals were inaccessible:

He [Williams] has also commissioned new orchestrations of Broadway tunes and hewed to a generally higher standard than prevailed in the last Fiedler years—Williams likes to have older music, and current music, orchestrated in the style of its own period rather than gussied up into an omnipresent and rootless “Pops” style. (Dyer 1983, 43)

Figure 3

Concert program from the Boston Pops Orchestra, May 7, 1978.

Boston Pops. May–July 1980. John Williams Conductor. Boston: Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1980, 21.

Some of such reconstructed arrangements included “Singin’ in the Rain” (Nacho Herb Brown, Arthur Freed, Conrad Salinger) from Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952) and “The Trolley Song” by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blaine from Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincente Minnelli, 1944, music adapted by Roger Edens) both based on Conrad Salinger’s original orchestrations.

The better quality and philological care of the arrangements were central ingredients in Williams’s success in rebalancing the Pops to the centrum of the low-brow/high-brow spectrum. This rebalancing was a subtle adjustment that introduced inner changes, not a drastic change liable to upset the tradition and the time-honed exterior format—in Williams’ words, “We have to reinvent the Pops, but think about it in terms of change that is evolutionary and not revolutionary, because we have a responsibility to our enormous audience as well” (“Williams Returns to the Pops with His Evolutionary Plans” 1984).6

What was expected by many observers in 1980 to be just a temporary and short-lived occupation for the Hollywood composer (Pfeifer 1982), on the contrary, ended up lasting for a fourteen-season tenure. At the time of Williams’s retirement in 1993, the Boston Globe music critic Richard Dyer described the conductor’s overall contribution in these terms:

Williams succeeded because it simply didn’t occur to him to try to imitate Arthur Fiedler, any more than it occurred to him to remake the Pops in his own image. […] He brought his own missionary zeal to the cause of film music, and not just his own. […] His ear told him when an arrangement was dated and needed to be replaced; he and his team were as alert as Fiedler was to what was going on around him and what the Pops could use. He could also clean an arrangement up in less time than it would take someone else just to rehearse. He believed that serious composers should be encouraged to write light music, so the Pops commissioned new pieces nearly every year. […] Williams conducts Pops music because he honestly believes in its value and its role in American life. […] John Williams once said that he has spent his life as a working musician, and he has. It has been a life that has made a difference, that still makes a difference, because everything he does is always just a little bit better than it needs to be. That’s just the way John Williams is. (Dyer 1993a, 33–37)

The Boston Symphony Orchestra music historian Steven Ledbetter also stressed Williams’s success in increasing the international visibility of the Boston Pops:

In addition to leading the Pops at home and on a lengthy series of best-selling recordings, John Williams has brought Boston to the world, both on widely televised appearances such as the Statue of Liberty Centennial in 1986 and on extraordinarily successful tours with the Boston Pops Orchestra and the Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra, including appearances in Japan in 1987 and 1990. The orchestra celebrated its centennial in 1985, with various activities led by Mr. Williams to affirm its position as the preeminent ensemble for pops repertory. (Ledbetter 1993, 30–31)

Williams’s achievements at the end of his tenure have been summarised as follows:

13 seasons [14, actually], more than 300 concerts, six national or international tours, 24 premieres and commissions, 28 CDs and nearly 50 television shows. Along the way, Williams has brought some of the leading artists of several musical worlds to the Pops […] Williams took from Fiedler what worked: the shape of the program, the mix of music, putting the spotlight not only on celebrities but on members of the orchestra and young musicians. Williams improved discipline and morale and raised the standard of performance. (Dyer 1993b)7

Williams’s other career as a conductor did not end when he resigned from his Boston post, because he was given the title of “Boston Pops Laureate Conductor” and has continued to be an active part of the Boston Symphony family—for example, with his annual presence at the Tanglewood Music Festival, the BSO’s summer headquarters, as “Artist in Residence”—and to give concerts with the orchestra regularly, in what became the much-awaited “John Williams Film Night” concerts. Nor was his conductor’s career limited to the Boston Pops. Once he accepted the Pops conductorship, Williams received a mounting number of invitations as guest conductor from other orchestras, which included such top institutions as the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the National Symphony Orchestra. He made further appearances at the Royal Albert Hall for those FilmHarmonic concerts that had seen him debuting as a concert conductor (for example, in 1980 with the National Philharmonic Orchestra). He also gave concerts with the Star Wars orchestra, the London Symphony, starting in 1978. Williams guest-conducted in the US, in Japan, and in the UK, while he had never given concerts in continental Europe, until his nineties. After a two-year delay due to health issues, he debuted with the Wiener Philharmoniker, perhaps the epitome of European art-music protectionism, on January 18, 2020, at the age of 87. This was a concert of truly historic significance, because the Wiener Philharmoniker had never given an entire film-music concert before, led by a Hollywood composer, in their prestigious Musikverein hall in Vienna. The presence of the world-renowned classical violin virtuoso Anne-Sophie Mutter as the concert’s soloist added further lustre to the event, an ulterior attestation of acceptance of the film-music repertoire from the “classical” circles. The Vienna concert was followed by two other historic debuts for Williams and for Hollywood film music: the Berlin concerts with the Berliner Philharmoniker in October 2021 and Williams’s debut, at 90, with the Filarmonica de La Scala in Milan, in December 2022, in the temple of Italian opera, La Scala theatre. On that occasion, Italian reviewers praised the orchestra for having invited the veteran composer and lauded the event, which managed to finally bring into the venerable theatre younger and more vital patrons than those who typically are to be seen at La Scala (Giacomotti 2022). The recent European concerts were yet another step in that mission of bringing symphonic music to the masses that Williams had started with his film-composer work and had continued with his job at the Pops, and then as an indefatigable guest conductor—in September 2023, at 91, he travelled to Japan for two concerts with the Saito Kinen Orchestra.

Composer as a conductor / conductor as a composer

From the above survey, it is clear that Williams’s activity as a conductor cannot simply be considered a part-time sporadic diversion. His conductor’s career was so substantial and continuative as to prompt one to consider it parallel, not secondary, to his much more studied composer’s career. The two career paths can be seen not only as parallel but also as integrated and interdependent, at least from Star Wars onwards, when Williams’s “neoclassical” (Audissino 2021b, 135–147) revival of symphonic film music had been successfully established. Around that time, Williams was increasingly showing a remarkable preoccupation for the concert adaptation of his film scores, the first instances being identifiable in the concert adaptations of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind encouraged by the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1977. The Star Wars suite published by Warner Bros. Music—running approximately thirty minutes and featuring, as written on the score’s table of contents, the “Main Title,” “The Little People,” “Here They Come,” “Princess Leia’s Theme,” “The Cantina Band” (optional, scored for a small jazz combo), “The Battle;” “The Throne Room and End Titles”—enjoyed a wide success and, between 1977 and 1979, the rental numbers tallied around 400 performances (Livingstone 1980, 76). Williams’s film music was gradually entering the symphonic repertoire, at least that of Pops orchestras—like the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra—or of Pops programmes, like those with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Williams’s appointment at the Boston Pops provided a timely and compellingly visible rostrum from which to showcase film music’s viability as a concert repertoire.

It can be said that Williams acted as an advocate for the legitimacy and viability of the film-music repertoire as a source for new concert pieces. Though, similarly to the statement about not having intended to conduct in public, Williams has also been characteristically anticlimactic in his downplaying of the matter of concert adaptations of his film score:

If I can take the music out of the soundtrack and have it almost resemble music, this is a minor miracle, and a double asset. […] If I write a 100-minute score, there may be 20 minutes that could be extracted and played. The other 80 minutes is functional accompaniment that could never stand on its own and was never intended to. (Stearns 1993, 22)

The statement, though, can be contrasted with Jack Sullivan’s correct annotation that “Williams envisions his projects as cinematic concerts” (Sullivan 2017, 186). Indeed, even before the Star Wars concert presentations and at least since Jaws—which featured the “Preparing the Cage” fugato and the “One Barrel Chase” Korngoldian symphonic scherzo—Williams had clearly shown an awareness of the concert-performance potentials of his film scores. Three attitudes betray such undeniable interest in the future concert life of selections—often many selections—from his film scores.

First, we have the use of classical forms from the art-music practice, an aspect that challenges the general opinion that film music’s fragmentary nature makes it necessarily refractory to traditional musical forms (Prendergast 1977, 215–233). Williams often mobilises musical forms that are akin to those of art music: mentioning only a few examples, the scherzo in Jane Eyre, in Dracula (John Badham, 1979), in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (Steven Spielberg, 1989), in Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (J. J. Abrams, 2015); the fugato in Jaws, in Black Sunday (John Frankenheimer, 1977), in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Alfonso Cuaron, 2004); stand-alone pieces for chorus and orchestra, like the carols in Home Alone (Chris Columbus, 1990), the “Gloria” in Monsignor (Frank Perry, 1982), “Exsultate Justi” in Empire of the Sun (Steven Spielberg, 1987), and “Hymn to the Fallen” in Saving Private Ryan (Steven Spielberg, 1998); action scenes scored like ballet numbers, for example in Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993) or in Hook (Steven Spielberg, 1991). Williams employs traditional forms in some cues in his film scores that are almost ready as they are for a concert presentation: if a coda is added to close a passage left open in the film score, we have “The Asteroid Field” concert piece from Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back or “The Lost Boys Ballet” from Hook. From the finale cues for E.T. The Extraterrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982) Williams adapted—with the mere deletion of a few central measures—what is known in concert programmes as Adventures on Earth. The musicologist Sergio Miceli—characteristically stern in his judgement of Hollywood music—singled out the merits of this concert version: “Thanks to its thematic concatenations, the piece alludes convincingly to the musical macro-forms of the Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries […] showing a musical legitimacy rarely to be found in film-music adaptations” (Miceli 2009, 249–250).

A second sign of Williams’s concern for the stand-alone life of his film works is the simultaneous composition of the film score and a set of expanded or reworked cues that are recorded specifically for the related LP albums, a practice in which Henry Mancini excelled (although in his case this applied to the creation of easy-listening pop albums). With Williams, the results are sorts of suites of adapted cues from the film score, as in the case of the Jaws or the Star Wars albums, or symphonic poems, as is the case for the E.T. The Extraterrestrial album. A significant example is The Fury (Brian De Palma, 1978): the film music track (23 cues and 55 minutes of music) was recorded with a studio orchestra in Los Angeles, while for the album Williams decided to record the nine entries of the forty-minute suite with the London Symphony Orchestra in the UK. Selections from the film score would be expressly expanded and re-arranged for the albums, in order to provide a better musical solidity and closure; but the track list would also be re-arranged in a different order than the cues’ appearance in the film, to pursue criteria of musical variety and balance aimed at an autonomous music experience. The LP album of Star Wars constitutes a good illustration: the “The Little People Work” track follows “Ben’s Death and TIE Fighter Attack,” in reverse order than they appear in the film; The “Main Title” in the album is the combination of the cue that opens the film, over the crawling titles, with the cue that plays over the end credits—Williams explained, in the album’s liner notes: “I combined part of the end title with the opening music to give the beginning of the record the feeling of an overture” (Williams 1977). A comparison of the 1982 LP album of E.T. The Extraterrestrial (MCA Records 1982, CD, MCLD 19021) with the cues written for the film provides some examples of such adaptation procedures. The film cue for the Halloween sequence and the following bicycle flight over the moon (“The Magic of Halloween”) lasts 02:53, while the album track titled “E.T.’s Halloween” lasts 04:07. The album version expands the opening staccato march for oboes, bassoons, and muted trumpets by lengthening the trumpets phrase and repeating the comically faltering opening motif for oboes and bassoons, now backed by Prokofievian staccato strings; then the majestic horns motif heard as the bicycle runs through the forest is enriched with a counterpoint by the flutes that anticipates the motivic material of the next section, unlike in the film cue; the crescendo section that leads to the flying theme is coloured by a more foregrounded piano part; the music for the flying scene is expanded through a double statement of the flying theme, and closed by a prolonged finale by the flutes that leads to a gradual deflation to the piece, unlike the more abrupt closure of the film track, in which the flying theme is interrupted as the bicycle hits the ground.

The third indicator of Williams’s concern for film music’s concert potentials is the recurrent presence of world-class “classical” soloists invited to record the film scores and albums. Their presence entails the inclusion in the film compositions of parts that are musically interesting and challenging enough to cater to the virtuosic and interpretive skills of the guest soloists. Examples of such esteemed musicians are the violinist Isaac Stern for Fiddler on the Roof; the percussionist Stomu Yamash’ta for Images (Robert Altman, 1972); the harmonicist Toots Thielemans for The Sugarland Express (Steven Spielberg, 1974); the trumpeter Tim Morrison for Born on the Fourth of July (Oliver Stone, 1989) and JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991); the violinist Itzhak Perlman for Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg, 1994) and Memoirs of a Geisha (Rob Marshall, 2005); the cellist Yo-Yo Ma for Seven Years in Tibet (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1997) and Memoirs of a Geisha; the guitarist Christopher Parkening for Stepmom (Chris Columbus, 1998); the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—in their first, and so far only, foray into film scoring—for Lincoln (Steven Spielberg, 2012); the star conductor Gustavo Dudamel as a guest-conductor for selected cues in Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens; the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (James Mangold, 2023). The involvement of these illustrious performers has generated a wealth of film-music pieces for solo and orchestra which are ready to become concert pieces for soloist and orchestra—Williams’s eight-minute-long Elegy, a concert piece for cello and orchestra, originated from the one-minute cue “Regaining a Son” from Seven Years in Tibet, which had the cellist Yo-Yo Ma as guest soloist.8

From his appointment as Boston Pops conductor, we can say that Williams has further developed such attention to the concert viability of his film scores: being a composer was still his principal occupation and preoccupation, but he would make sure that the film score should serve the film’s need while at the same time provide substantial musical materials, and in the proper formal coherence, as to offer suitable excerpts for concert presentations. The vast majority of the scores that Williams composed since 1980 originated some concert piece that was premiered with the Boston Pops, from single pieces—for example, “Theme” from The Accidental Tourist (Lawrence Kasdan, 1988) or “Dry Your Tears, Afrika” from Amistad (Steven Spielberg, 1997)—to suites of various length, for example, one from The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987) that includes “The Tennis Game,” “Balloon Sequence,” “Devil’s Dance,”9 or the one from Hook, consisting of “The Flight to Neverland,” “The Face of Pan,” “Smee’s Plan,” “The Banquet Scene”), and one from Schindler’s List (“Theme,” “Jewish Town (Krakow Ghetto – Winter ‘41),” “Remembrances”).

Williams has retained this attention to the extrafilmic life of film music up to the present day, despite the current dominant film-music style. After the year 2000, Hollywood saw radical changes in its workflow, moving from the old-school analogue and linear post-production processes to digital and non-linear ones, and such changes impacted on the post-2000 style of film music, as I have examined elsewhere (Audissino 2022). Post-production executed on Avid Media Composer, or similar editing software, and Digital Audio Workstations had the effect of requiring film music to be more compatible with the resulting thicker sound design and more flexible for the more hectic editing pace. This meant that music has been increasingly less melodic and polyphonic, and more percussion-based and visceral. The frequent re-editing of the film and the changes that could now happen until the very last moment necessitate a type of music that can also be as easily and swiftly modified at the last moment: a more modular and non-structured type of composition, eschewing longer patterns, developments, or forms (Audissino 2022). One of Williams’s characteristic compositional techniques is the “gradual disclosure of the main theme” (Audissino 2021b, 145–147, 293), a way in which a musical theme is at first presented fragmentarily and then in increasingly larger chunks—so as to make the audience familiar with it across the film—and finally presented in its entirety during some emotionally strong moment in the film. The “pleasure of recognition” (Meyer 1996, 210, n.185) of finally hearing the entire theme that had previously been only foreshadowed triggers a satisfying reaction that is liable to boost the emotional moment in the film. A textbook example is the “Flying Theme” in E.T. The Extraterrestrial, which is presented in its full form during the flying-over-the-moon sequence (Audissino 2017a, 206–207). Such extended design of the film score—the “teleological genesis” (Schneller 2014, 99) that makes Williams’s film scores singular in their formal cohesiveness—requires the composer to watch the film in its entirety, so as to be able to map such extended thematic revelation across the narrative, and it also requires the film’s cut to remain relatively unchanged from the moment in which the composer “spots” the rough cut to write down the timings, to when the score is recorded, to when the recorded music is dubbed onto the final cut of the film. This completeness and stability of the working cut is no longer the case in contemporary Hollywood cinema.

Williams had already modified his idiom in the second Star Wars trilogy to better fit the music within the now thicker sound-effects stems, making the music more percussive and with an emphasis on the high and low range, instead of the more melodic and middle-range writing of the first trilogy (Audissino 2017b). With the third trilogy, it is clear that Williams also had to discard his “gradual disclosure of the main theme” approach, not only because with such thick sound design it would be pointless to write extended melodies as in the first trilogy, but more importantly because Williams never got to see an entire cut of the whole film, as he was compelled to work only on disconnected chunks of the films. Fragmentariness has come in hand with unstableness, as these films have typically also been liable to be recut and changed dramatically, also involving reshoots of the ending—as happened also with Indiana Jones and The Dial of Destiny, an information that was disclosed by Williams himself during his concert at La Scala in Milan (December 12, 2022). If the composer lacks a complete view of the film, and if the film is highly unstable and liable to change until the very last minute, it is inevitable that the film score cannot be designed in a developmental and extended-design manner, as happened before.

A consequence of this forced adaptation to the new more fluid workflow, Williams has increased the amount of “recycled” materials in the third Star Wars trilogy and the fifth Indiana Jones instalment—for example, the cue “Auction at Hotel L’Atlantique” in Indiana Jones V sounds as if repurposing parts of the cue “The Duel” from The Adventures of Tintin (Steven Spielberg, 2011). This might be interpreted as a way to, resignedly, face the new demands of the industry, a sort of autopilot coping mechanism. Yet, to counter this interpretation, Williams has kept producing concert pieces out of these latest scores, perhaps redirecting, under such novel working conditions, the bulk of his attention from the music as featured in the film to the music as playable on the concert stage. An entire new suite was derived from Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens, also including an intricate fugato march (“The March of the Resistance”) and a virtuoso showcase for the brass (“Scherzo for X Wings”). For Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017) he created a theme for Rose, a secondary character, on which is built a five-minute-long concert piece titled “The Rebellion Is Reborn.” His collaboration with John Powell for the Star Wars spin-off Solo: A Star Wars Story (Ron Howard, 2018) produced the Han Solo theme at the basis of the concert work “The Adventures of Han,” another virtuoso action scherzo. If the score to Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is not as rich as the previous instalments in thematic material, it is nevertheless dominated by “Helena’s Theme,” a richly “old-school” romantic piece which Williams conceived at the same time as a concert piece written expressly for Anne-Sophie Mutter, showcased over the end credits. Some of the aforementioned pieces were brought to Europe in Williams’s tour of some of the top continental orchestras. “The Rebellion Is Reborn” was featured in the Vienna and Milan concerts; “The Adventures of Han” in the Berlin and Milan concerts; “Helena’s Theme” was played at La Scala, in Milan. Despite the changed working conditions for film composers in Hollywood and the adaptation of his own work routines to adjust to the new demands, Williams has managed to sustain his interest in the concert performability of film music and to carry on with the fruitful integration and interaction of his parallel careers. Williams the composer wrote a theme for the film and at the same time Williams the conductor saw the potential, or made sure there was the potential, for a concert piece in some part of the score.

Conclusions

Williams the conductor had begun his tenure at the Pops with personal hesitation and with some people’s concern about his lack of concert-conducting experience, something which some critics had questioned, if not openly and vitriolically condemned (Audissino 2014, 141–142). Yet, the final assessment of the reluctant conductor who had never intended to conduct in public was positive. A 1984 review of a Williams concert in Los Angeles already noted:

The orchestra offered […] a program of four traditional Russian works played about as splendidly as one could hope to hear them. Clearly John Willams, the much-maligned composer-conductor, deserves a hefty portion of the credit. He led the whole program with musical assurance, rhythmic incision and a welcome absence of indulgence. Indeed, Williams is much underrated as a serious conductor. He may or may not have revelatory insights into Beethoven, but he is certainly a solid musician who can keep an orchestra not only together, but also in the service of his soundly musical ideas. (Moss 1984)

Later on, in 1991, more praise was added:

When he conducted the current concertmaster Tamara Smirnova-Sajfar in the Tchaikovsky Concerto a few years back, he did a better job than some Boston Symphony guest conductors who come to mind, and there’s more than one celebrity recording of a popular concerto that would have been better if John Williams had conducted it. (Dyer 1991b)

The entirely positive review of Williams’s début in 1993 as guest conductor of the Boston Symphony in a programme of “serious” music pointed out: “Of course he could have had a career as a symphonic conductor if he had wanted it” (Dyer 1993c).

More importantly, Williams’s second career, one that blossomed serendipitously and unintendedly in the 1980s, proved to be the apt extension of what Williams had already been doing in the 1970s in his film works: the revival of symphonic film music and the presentation to the large audience of how engrossing and exciting the sound of an acoustic symphony orchestra can be. The conductorship of the Boston Pops allowed Williams to extend this mission from the film theatres to America’s most visible concert hall, Boston’s Symphony Hall. From the privileged Boston Pops podium, Williams was able to demonstrate the potentials of the film-music repertoire as a lively repository from which symphonic programmes could be freshened up.

It is amply evident that Williams’s conductorship of the Boston Pops had a seminal impact on the legitimisation of film music as concert music (Audissino 2021a, 58–65), and the latest stamps of approval have been the invitation to conduct top orchestras such as the Wiener Philharmoniker, the Berliner Philharmoniker, or the Filarmonica de La Scala, which only a few years ago would have not even touched this repertoire. The Vienna concert was particularly meaningful and symbolic. If Erich Wolfgang Korngold had brought European art music “From Vienna to Hollywood” (Taruskin 2005, 549), and then that late-Romantic idiom was discarded because it had become antiquated to the ears of the dominant Darmstadt modernists, Williams brought back “Hollywood to Vienna” in return. This, through Williams’s conducting activities, has given the almost century-old history of Hollywood music a neat sense of closure and circularity. Once vilified and disdained, film music has now come to be (more) accepted in the temples of art music. Within the tension between high-brow and low-brow, Williams has managed to achieve a rare balance, if not to contribute to discarding such passé categories altogether: “Williams’ importance is that he has constantly reminded us that lasting popular success is not incompatible with high artistic standards” (Dyer 1991b).

Consistent academic study on John Williams has started only too recently (Audissino 2018) and has tended to focus on John Williams the composer. More study is needed of the other facet of his artistic life, John Williams the conductor, a facet that should be neither ignored nor underestimated if one wishes to understand and appreciate his work to the fullest extent. The synergy between the composer and the conductor is demonstrably an essential drive of Williams’s artistry.