Introduction

In addition to its notoriously heterogeneous membership (Quirk et al., 1985: 438; Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 563), the English adverb class poses a further difficulty in that it traditionally includes words that have the same form as some adjectives. Hard, for instance, is analyzed either as an adjective, as in (1), or an adverb, as in (2), depending on the context in which it appears.

| (1) | I was raised to believe that the American dream was built on rewarding hard work. (COCA, 1992, SPOK: CBS_Special) |

| (2) | They come in, and they work hard every day. And they get it done for their team. (COCA, 2018, NEWS: Omaha World-Herald) |

These adverbs, sometimes called flat adverbs, have not been the subject of major reconsideration, whereas some authors have not hesitated to question the boundaries between certain English word classes (see for instance the boundary between prepositions, adverbs and conjunctions, or between determinatives and pronouns, in Huddleston and Pullum, 2002). Words such as hard, early or long are far from isolated cases, as more and more adjectives can be used in contexts typically taken by adverbs, especially in informal English, as can be seen in (3).

| (3) | “Not everybody can bust out of the gate and play great baseball every year,” Thompson said. “We haven’t played great, but we haven’t played terrible, either.” (COCA, 1994, NEWS: Denver Post) |

In this example, the words great and terrible are used as manner adjuncts of the verb played, a function which is not possible for adjectives in traditional accounts of English grammar. As a consequence, these words are automatically classified as adverbs. Although informal – and sometimes even considered nonstandard –, the use of what looks like adjectives instead of their adverb counterparts is becoming more frequent. This raises the issue of the metalinguistic categorization of these words and of the relevance of the term flat adverb.

The article will begin by reviewing the complementarity between adjective and adverb in English and the difficulties involved in categorizing flat adverbs (Section 1). It will then outline a hierarchical classification method (Section 2) whose results will then be discussed (Section 3).

1. Adjectives and adverbs in English

1.1. Complementarity

In English, adjectives and adverbs are two established word classes that are systematically described together in major reference grammar books (Quirk et al., 1985: 399‑474; Biber et al., 2002: 184‑220; Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 525‑595; Carter and McCarthy, 2006: 236‑249). This systematic pairing is not random, since most members of those two categories exhibit a formal and distributional link.

Among the 200 most frequent adjective lemmas in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), 83,5% can form a derived adjective in ‑ly. On the other hand, there is a non-negligible number of adverbs that are morphologically simple (e.g. as, even, just, so, still, too, yet among the most frequent), and these tend to be more frequent in every type of text except academic prose (Biber et al., 2002: 194‑195). However, most English adverbial lexemes are complex and derived from existing adjectives through the suffix ‑ly.

These two word classes are also characterized by their complementary syntactic distribution. Indeed, adjectives and adverbs characteristically modify heads of different natures.

| (4) | As a result of rapid / *rapidly growth, little more than half the population is of working age. (COCA, 2012, WEB: oecdobserver.org) |

| (5) | According to Colonel Kim, the crowd grew rapidly / *rapid to about 1,500 people, mostly youths. (COCA, 1990, NEWS: CSMonitor) |

As shown in (4) and (5), nouns (such as growth) cannot be modified by adverbs, and verbs (such as grow, here in the preterite form) cannot be modified by adjectives. Members of either class only modify words from specific classes and are barred from modifying each other’s head types. The main distinction lies therefore “between adjectives, which modify only nouns, and adverbs, which modify all the other categories – verbs, adjectives, prepositions, determinatives, and other adverbs” (Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 526). It would therefore seem that the situation is simple: adverbs, even those which are not derived from adjectives, occur in syntactic functions in which adjectives cannot appear.

1.2. Properties of English adjectives and adverbs

Apart from the fact that they are syntactically complementary, the classes of adjectives and adverbs are also defined by their own distinctive properties.

According to Quirk et al. (1985: 472‑473), there are four properties that are characteristic of adjectives:

- They can occur freely in attributive function (a hungry child).

- They can occur freely in predictive function (the child is hungry).

- They can be modified by the degree adverb very.

- They can have comparative and superlative forms, either inflectional or through the use of modifiers more and most (I am hungrier than ever).

Quirk et al. (1985: 473) nevertheless recognize that there are adjectives that are more typical than others. While the adjective hungry has all the properties listed above, utter only has one (attributive function), which makes it a marginal member of this word class.

Adverbs are often harder to define because of their residual status. Some linguists (e.g. Quirk et al., 1985: 441; Biber et al., 2002: 193) only define adverbs through the fact that they can function as modifiers of diverse words or phrases (adjectives, adverbs, verbs, prepositions, noun phrases). Carter and McCarthy (2006: 242) add that among adverbs, many are gradable and many are derived from adjectives by adding the suffix ‑ly.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 563), who notoriously reduced the extension of the adverb class, also believe that the most important property to define adverbs is the fact that they can be used to modify all categories except nouns. The other characteristic that the authors put forward is that the class includes all the words that can have the same syntactic function as those that are derived from adjectives through the suffix ‑ly (e.g. often → regularly, very → extremely, maybe → possibly, moreover → additionally). Apart from that, adverbs are mostly distinguished from other word classes by their negative properties, i.e. by what they cannot do (for instance, they cannot function as a subject or a predicative complement).

There are other properties which are exhibited by adjectives, but which are not necessarily highlighted by linguists because they do not deem them to be defining or distinctive enough. For instance, many adjectives can be prefixed with un‑ (e.g. unable, uneasy, unimportant, untrue) to denote their scalar opposite, but this property does not seem to be salient enough to be used in grammatical descriptions. As a result, it will not be mentioned when considering typically adjectival properties in the rest of this article.

1.3. The issue of flat adverbs

Despite this division of labor between adjectives and adverbs, some linguists (Quirk et al., 1985: 405‑406; Biber et al., 2002: 195‑196; Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 567‑568) identify a subcategory of adverbs which have the same form as an existing adjective. These are sometimes called flat adverbs (Earle, 1871: 361; Gregori and García Pastor, 2008: 125; O’Conner and Kellerman, 2009: 30), as opposed to adverbs which are formed by derivation, especially through the suffix ‑ly. Flat adverbs are therefore adverbs which are homonymous with adjectives.

Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 567‑568) make a distinction between three subcategories of flat adverbs. The first category comprises adverbs whose use is stylistically neutral: they are standard and can be used in any register. Among this category, the authors make a distinction between adjectives that do not have an adverb equivalent in ‑ly with the same meaning (e.g. early, fast, hard, long) and those that do but whose form in ‑ly cannot be used in the same contexts (e.g. deep, loud, mighty, slow).

| (6) | It’s characterized by strong protections against firing workers and generous early retirement plans. (COCA, 2005, NEWS: CSMonitor) | |

| (7) | Me and my partner of 20 years have always planned on retiring early and do something we love. (COCA, 2012, WEB: http://videocafe.crooksandliars.com/heather/you-want-raise-retirement-age-walk-mile-ou) | |

Although the two instances of early in (6) and (7) are identical in form, the former is identified as an adjective based on its occurrence as a pre-head modifier of a noun, while the other is an adverb because it functions as the time adjunct of a verb.

The second category is constituted by flat adverbs which can be used in standard but informal contexts, and which could always be replaced by their version in ‑ly. The only example the authors give is the word real, which when used as an adverb – as illustrated in (8) – could always be replaced by the form really.

| (8) | Can I ask you a question real quick? (COCA, 2016, SPOK: NBC Today Show) |

Finally, Huddleston and Pullum put forward a third category of flat adverbs which can only be used in nonstandard speech. In these contexts, the authors consider that the overlap between adjectives and flat adverbs is greater. Indeed, examples of flat adverbs from this category can be found in transcripts of spoken conversations, movie scripts, and blog posts – contexts in which informal nonstandard language can be often encountered. The word quick in (8) is an example, as is the word serious in (9) or the words great and terrible in (3) – in these examples taken from spoken sources, both are used as manner adjuncts, a function traditionally filled by adverbs.

| (9) | This is about messaging. Which is really consistent with his approach here which is he is not unfortunately, he is really not taking serious the idea of running a country. (COCA, 2017, SPOK: CNN Tonight) |

It seems that in those informal contexts, an increasing number of adjectives are used in syntactic functions in which adverbs are expected, especially the adjunct function. Since these are typically adverbial contexts, linguists assume that those words are indeed adverbs. But given that this is a growing phenomenon, and that in a nonstandard linguistic context we can expect any semantically compatible adjective to be used as an adverb, the boundary between the two categories is becoming increasingly porous.

While the traditional view is that flat adverbs have just been converted, i.e. zero-derived, from adjectives, an alternative point of view is that these words remain adjectives, but that their use was extended to certain typically adverbial contexts. Because in many languages some words can have functions typically occupied by adjectives and adverbs in English (which Hallonsten Halling, 2018, calls general modifiers1), it is not unreasonable to consider that in English there is only one lexeme serious, real or quick which can be used to modify words from all categories. Cross-linguistics observations and the progressive systematicity of such a phenomenon in English could therefore make it unnecessary to posit the existence of two separate lexemes which would be specialized in modifying certain types of words to the exclusion of other words.

2. Method and results

2.1. Choice of the words analyzed

In order to see where flat adverbs lie on the gradient between adjectives and adverbs, only 37 flat adverbs recognized as such by Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 568) were taken into account, including real. These adverbs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: List of studied flat adverbs

|

alike alone clean clear daily dear deep direct |

early fast fine first flat free fucking hard |

high last late light likely long loud |

low mighty next outright plain real right |

scarce sharp slow strong sure tight wrong |

The view taken here is precategorial (Haspelmath, 2023) – the words listed are not considered to be inherently part of either category or to belong to two distinct categories depending on the context. Indeed, a word such as slow always has the same semantic content, whether it is used in typically adjectival or adverbial contexts. The only aspect that would play a role in positing two different lexemes for each form would not be morphology or potential modification, but syntactic distribution.

There are cases in English where syntactic distribution strongly correlates with morphology. Some forms can clearly belong to two or three different classes (noun, verb, adjective). The word round, for instance, will have different morphological possibilities depending on the syntactic context where it occurs:

- In verbal contexts, i.e. as the head of a clause, its possible forms are {round, rounds, rounded, rounding}.

- In nominal contexts, i.e. as the head of a noun phrase functioning as subject, object, predicative complement or complement of a preposition, its possible forms are {round, rounds}.

- In adjectival contexts, i.e. in attributive or predictive function, its possible forms are {round, rounder, roundest}.

In other words, a single form can safely be assigned to several word classes if a difference in syntactic distribution also corresponds to potential differences in morphological marking. It is not unreasonable to posit at least three2 distinct lexemes round, which therefore exhibit heterosemy (Lichtenberk, 1991), based on the morphological possibilities triggered by the syntactic distribution of the form. On the other hand, whereas a form such as early can occur in very diverse functions which would be considered either typically adjectival (e.g. pre-head noun modifier, predicative complement) or adverbial (e.g. time adjunct, complement of until), it can inflect for grade in all those contexts.

| (10) | I also want to ask about the title of your book; it’s also the title of one of your earlier poems. (COCA, 2019, MAG: Mother Jones) [pre-head modifier of poems] |

| (11) | Vicente was earlier than usual that evening. (COCA 2000 FIC: Feminist Studies) [subject-oriented predicative complement of was] |

| (12) | “That’s the same thing I saw earlier,” he said. (COCA 2016 FIC: Cabin, clearing, forest) [time adjunct of saw] |

| (13) | I actually didn’t even know that was the number until earlier in the year when somebody brought it up. (COCA, 2012, SPOK: CNN Piers Morgan Tonight) [complement of until] |

As can be seen from examples (10)‑(13), the typical context of use (adjectival or adverbial) has no effect on the possibility to use the comparative form or not. The morphology of the word cannot help decide whether these contexts require two different lexemes or not, and there is therefore no reason why early cannot be considered a single lexeme in all those contexts.

Rather, the analysis of the properties of the words listed in Table 1 will help establish whether each of them is closer to adjectives or adverbs in their current usage. As a baseline, words firmly established as adjectives and adverbs in a previous study of word classes (Delhem, forthcoming), and listed in Table 2, were added.

Table 2: List of words used for comparison

|

Established adjectives |

Established adverbs |

||||

|

able available beautiful big different difficult easy economic financial foreign |

full global great happy huge important large new nice old |

political possible recent serious significant similar simple small true |

actually again almost already also always certainly especially exactly |

finally here how maybe nearly never now often perhaps |

probably really recently simply sometimes soon then usually why |

2.2. Properties analyzed

From a metalinguistic point of view, word classes emerge because some words are believed to have enough grammatical properties in common to be brought together under a single label that will facilitate linguistic description (Crystal, 1966: 25). It is therefore paramount to take into account as many grammatical properties as possible when deciding how words cluster together into a common word class.

Each of the words listed in Table 1 and Table 2 was therefore analyzed according to 100 distinctive phonological, morphological, and syntactic properties. The properties include those that are generally used to define and distinguish adjectives and adverbs (see Section 1.2), but also properties that can be used to make distinctions between other word classes of English. They can be grouped as follows:

- Number of syllables.

- Stress pattern.

- Internal morphological structure (e.g. has the form ‹X‑ly›).

- Possible inflectional suffixes (comparative and superlative forms).

- Possible derivational prefixes (dis‑, in‑, un‑) and suffixes (‑dom, ‑hood, ‑ish, ‑ity, ‑ize, ‑ly).

- Possible complements (preposition phrases, clauses).

- Possible modifiers (comparative structure; noun phrase; adverbs enough, right, very; definite article; relative clause).

- Syntactic distribution as a complement of a verb (subject of be, subject of a lexical verb; postverbal complement of be, become, behave, give, go, last, need) or a preposition (specified preposition such as think about; until).

- Syntactic distribution as a modifier (adjunct of a verb in front, central, end position; modifier of a plain adjective, a comparative adjective, an adverb, a preposition; pre-head and post-head modifier of a noun).

- Agreement with the verb if in subject function.

- Possible coreferentiality with a personal pronoun.

- Status as a positively-oriented polarity-sensitive item (Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 829).

- Possibility to coordinate similar constituents.

Since word classification may be done by speakers over an unknown number of (mainly unconscious) criteria, none of these properties were weighted in order to make sure that no bias was applied to the study.

2.3. Hierarchical clustering

Once the properties of the selected words were transcribed in a spreadsheet, the dist function on R was used to determine the distance that each word had with the others. This distance should not be understood in the physical sense – it is rather a measurement of the degree of (dis)similarity between each of these units. Two words that behave in the exact same way will have a mutual distance of zero, and important differences in the morphosyntactic behavior of two words will translate to a higher distance between them.

Once the distance between each unit was determined, they were clustered in increasingly larger groups with the hclust function on R (Ward linkage). Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (forming increasingly larger groups) was chosen over divisive hierarchical clustering (breaking down big groups into increasingly smaller ones). This reflects the view that each word initially constitutes its own category, and words are then grouped with other words in larger classes if they share enough common properties. When clustering words together, the algorithm prioritizes words or existing clusters with the lowest mutual distance, until all words are part of a single cluster.

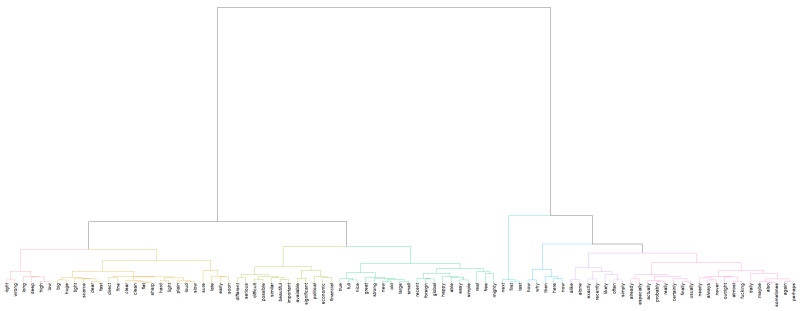

This kind of clustering method ensures that a word will belong to only one class in the end. It therefore yields clear results, with coherent resulting clusters comprising members that have at least some kind of family resemblance. The results of a clustering algorithm are generally shown in the form of a dendrogram, as can be seen for our units in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Agglomerative hierarchical clustering of English adjectives and adverbs

3. Discussion

The dendrogram in Figure 1 shows two clearly distinct clusters. One of them (cluster A) includes all words that are indisputably adjectives (e.g. available, difficult, financial, old), while the other (cluster B) includes all words that are indisputably adverbs (e.g. again, exactly, perhaps, sometimes). This shows that it is indeed possible to make a clear distinction between those two classes in English. The cluster in which the flat adverbs under study lie will therefore indicate the members of which word class each of them are closer to in terms of grammatical properties.

A quick look at the dendrogram shows that most flat adverbs under study belong to cluster A. Only 9 of the 37 units analyzed are rather part of cluster B. This means that when one examines all the different grammatical properties of English units, words classified as flat adverbs have more properties in common with words belonging to the class of adjectives than with those belonging to the class of adverbs.

Table 3 below compares the properties that are exhibited by a majority of established adjectives and adverbs, which can therefore be considered typical adjectival or adverbial properties, as well as the proportion of words belonging to cluster A which are traditionally classified as flat adverbs and which exhibit those properties.

Table 3: Proportion of words satisfying a given criterion according to its group

|

Property |

Established adjectives |

Established adverbs |

“Flat adverbs” in cluster A |

| Complex morphological form |

17% |

63% |

4% |

| Possible suffixation with ‑ly |

90% |

4% |

93% |

| Occurrence in as ~ as possible |

76% |

19% |

100% |

| Occurrence in more ~ than |

76% |

22% |

68% |

| Modifiable by very |

97% |

26% |

100% |

| Modifiable by enough |

90% |

15% |

100% |

| Modifiable by the |

72% |

0% |

36% |

| Subject of be |

72% |

22% |

21% |

| Complement of be |

100% |

22% |

100% |

| Complement of become |

90% |

0% |

96% |

| Adjunct in front position |

0% |

74% |

11% |

| Adjunct in central position |

0% |

81% |

11% |

| Adjunct in end position |

0% |

70% |

75% |

| Adjunct in detached end position |

0% |

74% |

18% |

| Modifier of good |

0% |

74% |

14% |

| Pre-head modifier of noun |

100% |

0% |

100% |

| Post-head modifier of something |

100% |

0% |

93% |

When comparing most flat adverbs with typical adjectival and adverbial properties, their clustering with adjectives becomes less surprising. This classification is indeed mainly due to the fact that they have most adjectival properties:

- They can be suffixed with ‑ly to create an adverb.

- They are gradable, which means that they can occur in comparative constructions and be modified by degree adverbs.

- They can occur in attributive and predicative functions.

On the other hand, those words have only one adverbial property: three quarters of them can function as adjunct of a verb in final, non-detached position. This is somewhat in agreement with Huddleston and Pullum’s (2002: 537) remark that nonstandard usage of flat adverbs is restricted to cases where they follow the head, i.e. the verb. Note, however, that this single property is logically not enough to move them over to the adverb class.

As mentioned above, only nine of those “flat adverbs” actually cluster with adverbs.

The three words first, last and next constitute a very coherent subcluster. They have a certain number of typically adjectival properties (attributive and predicative function, ability to function as head of a noun phrase) but lack other central properties that are characteristic of this class according to Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 528), namely gradability (*first enough, *as last as possible) and the ability to be in postpositive function (*someone next). In addition, what could have led the algorithm to cluster them with adverbs3 is their positional flexibility: they can function as adjuncts in all positions (front, central and end).

The other six words belonging to cluster B are alike, alone, daily, fucking, likely, and outright. The typical adjectival and adverbial properties (or lack thereof) are indicated in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Properties of flat adverbs belonging to cluster B

|

Property |

alike |

alone |

daily |

fucking |

likely |

outright |

| Complex morphological form |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Possible suffixation with ‑ly |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

| Occurrence in as ~ as |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Occurrence in more ~ than |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Modifiable by very |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Modifiable by enough |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Modifiable by the |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

| Subject of be |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

| Complement of be |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Complement of become |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Adjunct in front position |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Adjunct in central position |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Adjunct in end position |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

| Adjunct in detached end position |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

| Modifier of good |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

| Pre-head modifier of noun |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Post-head modifier of something |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

What is important to note in this table is not the number of adjectival or adverbial properties. The word alone, for instance, exhibits more adjectival (5) than adverbial (4) properties. This is not necessarily surprising, since in this table there are more properties that are typical of adjectives (11) than there are that are typical of adverbs (6). While this may seem unbalanced, the situation calls for two remarks:

- In English, adjectives have more positive properties than do adverbs, which are often defined negatively, hence the frequent status of the adverb class as a residual category.

- The total number of typical properties considered and the total number of typical properties exhibited by a certain word has no incident on its classification, since alone was clustered with adverbs despite its higher number of adjectival properties.

In the end, this classification shows that what counts is not the number of properties, but rather what properties those words have that other words do not, and vice versa.

The reason why those six words cluster with adverbs is because they characteristically lack one or several of the typical adjectival properties that were listed above: gradability (daily, fucking, outright), attributive function (alike, alone), or predicative function (fucking, outright). Moreover, none of them can form a derived adverb in ‑ly. Fucking is unique among those words in that it does not have many positive properties, and only one of them is adjectival (attributive function). Another complementary explanation is that these words have typically adverbial properties that are not necessarily shared with other “flat adverbs”: all of them are morphologically complex, most can function as adjuncts in several positions (notably the central position, which is uncharacteristic of other flat adverbs), and two of them can even be used as degree elements within adjective phrases.

Conclusion

If one considers that, for each of the words studied in this article, there is only one lexeme, the situation can be viewed in two different ways.

It is first possible to consider, as in this article, that the categorization of a given lexeme emerges from the set of morphosyntactic contexts in which it can enter into. In this case, each lexeme will belong to a single category (despite results that may appear counter-intuitive), although it can be considered an unprototypical, or even marginal, member of that category. For example, the adverb alone has a number of adverbial features, but not all of them, as well as a number of features that can be considered adjectival, which will not be the case for the other members of its class.

The other possibility is to consider that words have no inherent category – their categorization emerges in discourse depending on the morphosyntactic context in which they appear. In that case, the word alone will have adjectival or adverbial uses depending on its syntactic distribution in a given specific context. However, this solution implies determining a limited number of categories beforehand (which would include adjectival and adverbial uses, among others) and deciding arbitrarily that a given syntactic distribution corresponds to a predetermined category or use. This solution has not been preferred in this article, because it implies deciding arbitrarily on the reserved domain of a given class, usually using labels inherited from ancient grammatical traditions.

It is therefore safe to think, in light of the data presented and the emerging uses of some adjectives described earlier, that most words that resemble adjectives but function as adjuncts in final position are indeed adjectives and not adverbs. This way of categorizing “flat adverbs” allows for considering that there is an ongoing evolution among some adjectives of contemporary English. Under this view, a new possible syntactic function (adjunct of a verb in end position) is being progressively opened to a larger number of adjectives without systematically and artificially positing a conversion from adjective to adverb. Besides, not systematically considering words in adjunct function as adverbs also makes it possible to preserve the relative orthogonality of the notions of word class and syntactic function (Huddleston and Pullum, 2002: 355).

The issue studied in this article also raises the more general question of polycategoriality in English. Some English word unambiguously belong to one class (e.g. government is a noun, become is a verb, beautiful is an adjective) while others are more flexible (e.g. as, round, that, work). Given the fact that words can easily undergo conversion in English and that word classes are not necessarily real outside their function in grammatical description, systematically positing heterosemy is not necessarily the most parsimonious explanation. It is hard to decide, however, if word classes are becoming increasingly fuzzy (e.g. the words work or love show that the boundary between verbs and nouns is porous in English) or if it is better to work with smaller classes of morphosyntactically flexible words (e.g. work and love are neither nouns nor verbs but part of a distinct class of words that can occur in more diverse morphosyntactic contexts). How the word-class system of English actually works is therefore a bit more unclear and there might not be a definitive answer to provide.