Despite being known primarily for the brilliance of his orchestral scores, John Williams’s career has actually featured quite a lot of piano. From the early jazz recordings of the mid-1950s that display his virtuosic skills all the way up to his piano-filled score for Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans (2022), the instrument remained a familiar presence. We could also consider the many statements about his habit of composing from the piano multiple hours per day, or the several photos and videos showing him at his instrument, as further evidence of the piano’s prominence in his work.1 These aspects of his career all deserve attention in their own right. This article, however, will address yet another aspect of symphonism that has long been sidelined in scholarship, despite its ubiquity throughout John Williams’s career: the piano arrangements of his film and concert works.

During the nineteenth century, and until the early twentieth century, the vast majority of orchestral, vocal, and chamber music in all genres was published in piano arrangements. The works of Haydn, Beethoven, Mahler, Debussy, even Stravinsky, along with hundreds of others, found their way to the pianos of amateur musicians who would play them in a domestic setting, either for their private enjoyment or for their friends and family. Professional pianists also introduced arrangements in their public concerts. Sources show, for instance, that Franz Liszt performed Beethoven’s symphonies at the piano far more often than his actual piano sonatas (Christensen 1999, 289).

A century later, John Williams did not escape this enduring practice. Even if, strictly speaking, he only composed a single work for solo piano, Conversations (2013, still unpublished at the time of this writing), piano arrangements of his music have appeared regularly since his early screen work in the 1960s, making him by far the most published and widely available film composer of any generation. While John Williams’s name alone is a major selling point in today’s sheet music market, there is a lot more at stake in these arrangements than mere opportunism from music publishers to sell easy and popular pieces to young piano students. The release in recent years of several albums of his music performed by talented pianists has shown that there is real interest in bringing such arrangements out of the domestic sphere of amateur music-making.2 At the very least, they provoke a different kind of response to his music, and to film music in general.

In this article, I examine the piano arrangements of John Williams’s music in order to explain their types and significance, how they relate to the symphonic tradition, and how they can be used by musicians and scholars. I focus exclusively on arrangements published and distributed by major companies, usually marketed at the general public shortly after a film’s release. The vast majority of these arrangements are not credited, and while publishers will occasionally advertise them as “approved by John Williams,” the composer’s involvement remains uncertain (with two exceptions discussed below)3. I thus leave aside for instance the work of musicians and fans who create their own arrangements and perform them on digital platforms like YouTube. Starting with a very brief history of film music arrangements for piano, I situate John Williams as a publishing artist in the context of a longer tradition of domestic music-making, drawing comparisons with prior forms of symphonic arrangements while assessing the distinct issues raised by the film music repertoire. Although I refer to studies of nineteenth-century arrangements as a way to gain insight into the functions, techniques, and reception of this longstanding practice, I refrain from discussing the work of specific arrangers of the past, mostly because I look at Williams as arranged (by others, who usually remain anonymous) rather than as arranger (of others)—an important distinction to be made with studies of Liszt, for instance (see Kregor 2010; Kim 2019). I then approach these piano arrangements from two different angles to examine their suitability as musical texts for study, and their qualities as pieces for private and public audition. This double function of the repertoire of film music arrangements, wavering between scholarship and performance, underlines much of the dispute over its value. I follow Hyun Joo Kim’s argument about Liszt’s reworkings that “the two aspects [of fidelity and creativity] are actually complementary and mutually motivating, and interact in a dynamic way” (2019, 3).

A very brief history of film music arrangements for piano, from 1900 to John Williams

The publication of piano arrangements of film music can be seen as an extension of the market for arrangements of orchestral music, which was at its most lucrative in the second half of the nineteenth century. As Thomas Christensen put it: “no other medium was arguably so important to nineteenth-century musicians [than piano transcriptions] for the dissemination and iterability of concert repertory” (1999, 256). Numerous arrangements were sold for every genre—from the symphony to the opera, from the chamber sonata to the choral hymn—and by every major or minor composer. Four-hand piano arrangements were the primary medium through which people heard symphonic music, especially in cities where orchestral concerts did not happen regularly, if ever at all. Playing these arrangements at home blended musical education, sociability, and entertainment.

Arrangements of large-scale symphonic music fell in popularity in the early 1900s, as did piano sales and domestic music-making as an activity. The radio and phonograph recordings gave unprecedented access to musical performances in their original form, reducing the need to rely on arrangements to hear the concert repertoire. Yet, as Peter Szendy argued, the function of the arrangement was not merely to replace the original as a means of transmission, but rather to be complementary to it, to foster a “critical, active relationship with works” ([2001] 2008, 39).4 And therefore, the advent of recordings did not render arrangements entirely useless. As we will see, their commercial viability became increasingly tied to the promotion of audio (or audiovisual) products, while the arrangers could now better assume their distinct yet complementary functions. Publications of arrangements of popular music, especially of songs, which had long coexisted with the concert music repertoire, continued to thrive, eventually largely replacing the latter. In the United States, publishers based around New York’s so-called Tin Pan Alley now relied heavily on Broadway musicals, and eventually on the cinema, to provide them with a continuous flow of new hits to sell as sheet music (Garofalo 1999).

A decade before the advent of synchronized film sound, publications of music to accompany specific films or inspired by them were already part of publishers’ catalogues. The music that was sold may not even have been heard by moviegoers, but that was beside the point since they both served to promote one another. As the status and presence of music in film increased in the 1930s, so did sheet music publications (Smith 1998, 31). Interest resided mostly in songs taken either from movie musicals or adapted from movie themes with added lyrics. Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) was among the earliest movies for which several piano solo selections were published together in a folio, the term given to such collections.5 In the 1950s, as movies reached epic scales and soundtrack albums became more frequent, so too did piano folios, which ranged from 20 pages of music to over 50 pages—as in the case of Miklós Rózsa’s Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy, 1951)—even as the overall sales of sheet music were declining. By the 1990s, Donald Stubblebine’s imposing catalogue of Cinema Sheet Music listed publications for a staggering 6200 films (1991, 10).

While sheet music publications had largely turned toward popular songs, arrangements of non-vocal film music for piano revived and preserved an older tradition of symphonic music made available for domestic music-making—and this despite the availability of soundtrack recordings. During the 1960s (John Williams’s first decade as a film composer), a regular stream of piano folios presented generous excerpts of film scores including, among several others, such classics as Alex North’s Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz and Rouben Mamoulian, 1963), Henry Mancini’s The Pink Panther (Blake Edwards, 1963), and Maurice Jarre’s Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965). Although the context of their production and reception differed markedly from nineteenth-century piano arrangements of symphonic music, they both, each in their own ways, encouraged the circulation of orchestral scores outside of their original settings and promoted the participation of amateur musicians in the recreation of orchestral sounds at the piano.

It is in this context that arrangements of John Williams’s music were initially published. His first 25 or so publications fit squarely in the sheet music format established in previous decades for either title songs or movie themes: most pieces are brief enough to be printed on a single sheet of folded paper, and they serve to promote both the movie and its soundtrack. The sheet music for Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) can serve to illustrate how these three products—film, soundtrack, and sheet music—were interconnected. The front cover reproduced the movie poster, including the small print listing the co-stars, director, screenplay writer, producer, and composer (at the end of the second line, after the name of the novel’s author). It also showed information about the availability of the original soundtrack on MCA Records & Tapes. Only the words “Theme from” before the title, and “Piano Solo” after it, marked the cover as sheet music. Likewise, listings of the record, such as those found in the Billboard Hot 100 charts, included information about the sheet music supplier (in this case, MCA Music).6 This example shows that sheet music was—and largely remains—enmeshed in a larger market of promotional items, tie-ins, and merchandise. The ephemeral nature of this kind of movie memorabilia also means that these publications are not generally reprinted after their initial run, turning them into rare collectible items, and consequently leaving a lot of music inaccessible to new generations of musicians, collectors, and movie fans. Although the format of single sheet music did not change much after the early 1900s, its sales declined sharply after the 1950s (Smith 1998, 32). Its use for the publication of film music, however, practically disappeared in the early 2000s as it was gradually replaced by digital sheet music services, which left the folio as the only printed manifestation of most of John Williams’s scores on piano.7

After almost two decades of songs and themes printed as sheet music, John Williams’s first movie folio was published in 1977. According to Stephen Wright, Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) marked “a resurgence of film music publication” (2003, v). We have seen that film music publication was in no such need of a resurgence in 1977, and as we will see below, the Star Wars folio did not provide the generous musical content that was common in the 1960s.8 Nonetheless, the impact this movie had on soundtrack album sales, and Hollywood music in general, helped guarantee that John Williams’s following scores would almost all be published in piano arrangements. Since Star Wars, only 10 of his 66 scores have not received dedicated piano arrangements.9 In total, there are over 80 films and TV shows scored by John Williams for which music has been published, including 34 folios, far more than any other composer (for a complete listing, see Paré-Morin 2023).

Throughout the years, however, the criteria of this “resurgence” and the priorities of publishers evolved and did not always go together with the needs of pianists. We can trace the evolution of the publication format, style, and content of film music folios since the 1970s by comparing the first folio in each of the three Star Wars trilogies (1977, 1999, and 2015).

The original Star Wars folio contained only two arrangements for solo piano: the “Main Title” and “Princess Leia’s Theme”, totaling a mere four pages of music. 24 pages were dedicated to pictures, credits, and descriptions of all major characters from the movie. The remaining 36 pages were sketch scores of two cues reduced on four staves: the complete “Main Title” as it appears in the movie, and “Cantina Band” (I will return to these in the next section). Far from being a “resurgence of film music publication”, this folio did not mark a return to the format of the 1950s and ‘60s. In fact, whereas Miklós Rózsa’s folios, for instance, were clearly titled “Musical Highlights from…”, and Henry Mancini’s folios boasted the labeling of “Complete Score”, the purpose of the first Star Wars folio is rather ambiguous. The book’s heading suggested that this was much more (or much else) than just a piano music book: this was a “Deluxe Souvenir Folio of Music Selections, Photos and Stories.” The two brief piano solo arrangements here seem secondary. The oversimplified “Main Title” is immensely disappointing when the tantalizing orchestral reduction in sketch score appears just a few pages later. With so many pages of photos and texts, this folio certainly looks more like a souvenir product than an actual music book, something that could be collected along with the other toys, posters, books, and objects of all types that flooded the stores in the months following the movie’s release. Even more so than sheet music, folios thus acted, at least in part, as memorabilia since their illustrations and texts allowed the reader to revisit key scenes from the movie that they might otherwise be unable to rewatch.

Even in the Internet age, when pictures and videos from movies are just a click away, promotional material regularly includes references to the inclusion of “full-color artwork from the film” as a selling point (for example: on the Hal Leonard website or in the monthly Hal Leonard Herald). However, these pages make up for a much smaller portion of the more recent publications (see Table 1). On the other hand, the significant increase of music pages over the course of the three trilogies clearly indicates that publishers have gradually responded to a growing interest in film music and a rising demand for its piano arrangements. Furthermore, as the current digital market for sheet music splits folios into pieces that can be purchased separately, the former collectability of these publications matters far less, and their function as music rather than memorabilia is reinforced.

Table 1

| Star Wars (1977) | The Phantom Menace (George Lucas, 1999) | The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015) | |

| Piano solo pieces | 2 | 7 | 12 |

| Transcriptions of complete album tracks | 0 | 1 (+3 full cues within longer tracks) | 8 |

| Approx. duration | 4 min. | 13 min. | 34 min. |

| Non-music pages | 24 (37.5 %) | 13 (32.5 %) | 13 (18 %) |

Comparison of the folio contents of the first film of each Star Wars trilogy.

Studying film music through arrangements

The inclusion of sketch scores in the original Star Wars folio indicates that the publishers considered a variety of functions when publishing film music arrangements, with playability at the keyboard just one among others. What was referred to as sketch scores were faithful reductions of cues as heard in the film (or on the soundtrack album) on three to six staves of music, with occasional indications of instrumentation. The format originated in the early 1970s in some folios of rock albums, enabling amateur bands to perform covers more easily than by relying on a standard piano/vocal layout.10 The editorial decision to include “Cantina Band” from Star Wars as a sketch score rather than as a piano arrangement follows the same principle. However, the presentation of the film’s “Main Title” as a sketch score can hardly be played with any combination of instrument. Instead, it could serve to study the composition and to discover details in the orchestration that would otherwise be lost in a piano arrangement.

Only five sketch scores by John Williams were published between Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981) four years later (see Table 2).11 Their value cannot be underestimated, especially at a time when orchestral scores of these movies were not available to the public. To this day, the sketch score included in the folio of The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) constitutes the only available publication of the entire six-minute-long end credits suite. This score contains the only published arrangement of “The Imperial March” that preserves its original rhythmic ostinato, as opposed to the bland quarter-note accompaniment available in all other piano arrangements ever since.

Table 2

| Star Wars (1977) | ||

| • | “Main Title”: 4-staves transcription of the entire first cue, 98 bars | |

| • | “Cantina Band”: 4-staves transcription, 100 bars | |

| Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977) | ||

| • | “The Mother Ship and the Mountain (Resolution and End Title)”: 5- to 6-staves transcription of the first 52 bars of the end titles cue | |

| The Empire Strikes Back (1980) | ||

| • | “Finale”: 3- to 4-staves transcription of the entire finale and end credits cues, 156 bars | |

| Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) | ||

| • | “Raiders March”: 3-staves transcription, 71 bars | |

Complete list of John Williams sketch scores published in folios.

Although sketch scores were dropped after 1981, the gradual increase in pages dedicated to piano solo arrangements in the following decades means that a greater amount of music per film is now available in print and can be studied. Comparing again the first folio of each Star Wars trilogy is revealing. The number of piano pieces has gone up from two to seven to twelve by the time of The Force Awakens, eight of which present arrangements of complete album tracks (see Table 1). The folio for that movie provides the transcription of almost half of the album, or roughly 34 minutes of music, significantly more than the 13 minutes of music printed in The Phantom Menace folio, or the mere 4 minutes of piano arrangements in the original Star Wars folio. These arrangements provide the film music scholar as well as the fans an unprecedented access to John Williams’s music for study, all the more important since film scores are otherwise very rarely published. Thus, even though piano arrangements cannot replace a full orchestral score, they can provide more than a helpful guide to the study of these scores, and can serve as the basis for thematic, formal, and harmonic analysis.

Beyond John Williams’s film and TV work, thirteen of his celebration fanfares have been published as sheet music or in piano anthologies, including a handful of pieces from the late 1980s that have never been available on recordings: Celebration Fanfare (1986), We’re Lookin’ Good (1987), Fanfare for Ten Year Olds (1987), and Fanfare for Michael Dukakis (1988). For scholars or musicians interested in this aspect of the composer’s career, these long-out-of-print publications offer a rare opportunity to study or learn this music.

All this considered, one could be quite enthusiastic at the amount of printed material that can be used to study John Williams’s music. On The John Williams Piano Collection website, I have catalogued about 300 distinct pieces (Paré-Morin 2023), which is almost three times as much as published in full orchestral scores by Hal Leonard in their John Williams Signature Edition.

Unfortunately, several problems hinder the reliability of these arrangements as study material. Since the arrangements do not aim to provide a faithful recreation of the orchestral originals, many details are lost, such as contrapuntal lines, complex rhythmic figures, articulations, dynamics, and even melody notes. These arrangements are very far from the nineteenth-century ideals of music transcriptions that aimed to provide more or less accurate reductions of symphonic works. This is why Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl, a pianist who recorded several albums of his own virtuosic arrangements of John Williams’s music, writes:

These arrangements, conceived for amateur pianists, sever the pieces dramatically and simplify them to the point that one barely recognizes the original score. This horribly weak adaptation destroys the work’s genuine character and reduces it to the slight minimum—the main theme and a primitive accompaniment! A work of nine minutes for orchestra is accordingly compressed into a one-minute piece of two piano pages—just for the pleasure of the amateur performer claiming that he is capable of playing the “E.T. theme.”12

Recent publications have tended to avoid the excesses that Lühl complains about by including longer excerpts of film cues or full album tracks that preserve, as much as possible, the “genuine character” of the music. In the three folios of the Star Wars sequel trilogy, half of the pieces present full album tracks, including all major themes. Nonetheless, among the 37 arrangements published in these folios, about one third are shorter than two minutes. It is worth asking, however, whether this is the fault of the arrangers or of the fragmented nature of film cues. Regardless of length, it is undeniable that no single piano arrangement can come anywhere close to the textural and contrapuntal complexity of the symphonic scores. However, as I argue below, I believe that this is beside the point.

The most significant obstacle to the use of arrangements as study material is arguably the errors that permeate these publications and that often blur the line between technical simplification for the amateur pianists and misreading of the actual music. There is not much exaggeration in stating that there are musical errors in every single folio, severely limiting their usefulness as study scores.

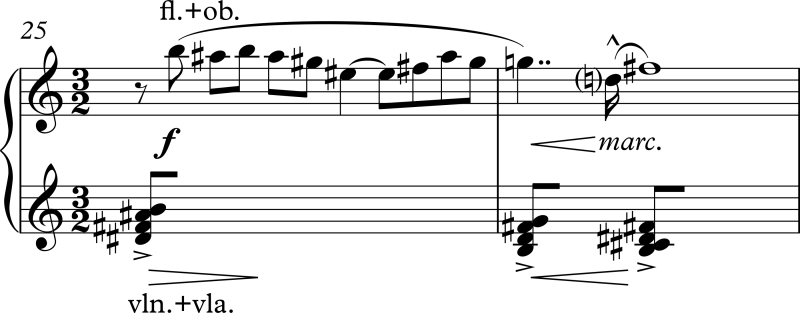

Since Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl highlights the “E.T. Theme” (also known as the “Flying Theme”) from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982) in his criticism cited above, let’s have a closer look at a two-measure excerpt as a striking example of the kind of misreading found in film music arrangements. After the grand opening statement of the main theme, a secondary theme in a much leaner texture is introduced in measures 25–26. The three flutes and two oboes play the melody in unison while the violins and violas provide a pulsating accompaniment on major 7th chords. A faithful transcription of this passage—one that renders the full orchestral score as closely as possible—should look like this (Figure 1):

Figure 1

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, transcription of “Flying Theme” (mm. 25–26) based on the published orchestral score. I am using a shorthand for the pulsating chords only for clarity.

The first piano arrangement published in the original folio made two important changes: it removed the major 7th from the chords and replaced the energetic pulsation of the strings with sustained chords (Figure 2):

Figure 2

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, arrangement of “Flying Theme” (mm. 25–26) as published in the original piano folio.13

Both changes might have been made to provide pianists with a simpler version, but a more accurate arrangement (as seen in Figure 1) would not have been much more difficult to perform and would still have been easier than several other passages in this folio. Consequently, the published arrangement is less rich harmonically and less active rhythmically than the original. Furthermore, the accompaniment is transposed down by an octave, which—along with the other changes—replaces the lightness of the orchestral strings by a slightly heavier and fuller sound. Finally, notice how the change from E-sharp to F-natural as the sixth note of the melody, perhaps again to simplify the readability, muddles the note’s function as a lower neighbour tone to the F-sharp. Together, all these minor changes—while far from the “horrible” and “primitive” adaptation described by Lühl—greatly affect the tone of the arrangement and, more crucially for us here, its usability for study.

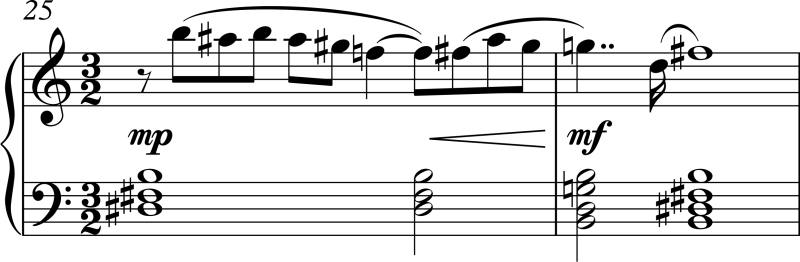

But the story of the “Flying Theme” does not stop here. The original folio arrangement has quietly been replaced in the latest anthologies and in digital stores by a slightly different version (Figure 3):

Figure 3

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, arrangement of “Flying Theme” (mm. 25–26) as published in current anthologies and digital stores.

The changes are highly questionable. In the first measure, the last four notes of the melody are now unjustifiably read in the unrelated key of G-flat, while the left hand, instead of playing a B-major chord, is distorted into a diminished chord on F-natural! Whatever the reasons behind this “horrible” misreading,14 it departs so much from the score as written by John Williams that it fails to represent his music accurately, and for reasons that seem completely independent from the often-challenging process of arranging orchestral music for piano. In this case, we are lucky that the published orchestral score can be used for comparison and study, but for the vast majority of piano arrangements—for which orchestral scores have never been published—we can only rely on our ears to fix the errors, or else blindly trust the (usually uncredited) arrangers.

So, in short, as material for study, these publications provide an incredible amount of music that remains unavailable in any other form, and even a few pieces that have never been properly recorded. They should be highly valued as such. As Stephen Wright put it: “These published arrangements are significant because, in most cases, they are the only readily available printed manifestation of the score, thus the only published notation of what the composer wrote” (2003, vi). But the simplification and unreliability must be taken into account if they are to be used for study, especially for musical analysis.

Playing arrangements at home and in concert

For these reasons it is perhaps best to view piano arrangements of film music primarily as pieces to be played, either for private enjoyment or in recitals, rather than scores to be studied. Unlike nineteenth-century arrangements published as a means to hear large-scale works that would otherwise be impossible to hear, film music arrangements do not need to stand as substitutes for the orchestral sounds, allowing for much more deviation from the compositions as heard on screen. For Mike Matessino, the reason to value such arrangements is because they grant direct contact with the music: “Playing Star Wars music on [piano] is, in fact, a close encounter with the composer who created this indelible, galaxy-spanning odyssey, unfathomable in both its scope and in its rewards to performer and listener alike” (2023). Performing film music on piano allows the musician to develop a new relation to the composer, one that is almost intimate, and therefore personal or individual15. This is the experience that some listeners have shared with regards to the performance of John Williams’s music on piano, as I discuss at the end of this article. For the moment, it is essential to stress that piano arrangements as repertoire must be valued on their own, and not for how well they approximate the orchestra.

Despite the substantial differences between the production context of film music and that of symphonic music of previous centuries, I would argue that the criteria for a good piano arrangement do not differ much between them. Here is how Thomas Christensen discussed the quality of nineteenth-century arrangements: “The key to a successful piano transcription […] was knowing what to leave out as much as what to put in. The most effective ones were naturally those that were sensitive to the sounds of the piano and the idiom of keyboard realization. Finding appropriate substitutions for orchestral sonorities and textures […] taxed the most inventive of arrangers” (Christensen 1999, 270). On the one hand, arrangements that follow too closely the orchestral versions will be either difficult or clumsy to play. This is why, for example, the ostinato of “The Imperial March” must be simplified at the piano. But on the other hand, arrangements that oversimplify the orchestral texture will present little interest for both the pianist and the listener.

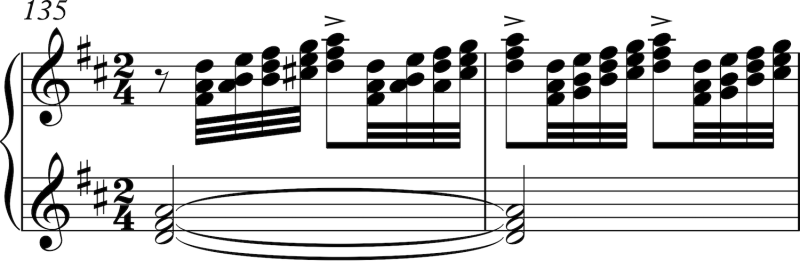

Most arrangements, especially in recent folios and anthologies, fall neatly somewhere in between these two extremes. But this has not always been the case with John Williams’s music. Over the years, many challenging or even technically unplayable arrangements were published. One of the most fiendishly difficult pieces is “The Devil’s Dance” from The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987), which contains some sections that are among the most exciting and rewarding to play alongside others that require virtuosic skills, such as frequent large jumps, fast octatonic scales, and alternating thirds (Figure 4). This example departs from mass-market arrangements of moderate difficulty and veers closer to Liszt’s concert approach, which, according to Jonathan Kregor, “privileges the foreign over the common, meaning that, say, typical left-hand accompanimental patterns or comfortable hand positions should not be expected” (2010, 30). It is perhaps because of its unusual length and demanding technique that this arrangement has never been reprinted despite the popularity of the piece itself.

Figure 4

The Witches of Eastwick, excerpt from the published piano arrangement of “The Devil’s Dance.”16

A recurring problem is the transcription of Williams’s characteristic rapid brass figures in his more ecstatic passages, especially in his celebration fanfares. For example, the following excerpt (Figure 5) taken from the end of the Liberty Fanfare (1986) shows the rendition of brilliant trumpet flourishes even though they are practically impossible to play on piano at the regular speed. Musicians (especially amateurs) who want to play these recurring figures will quickly realize that a more adequate alternative would be to perform only the top note of each chord as a quick scale in order to preserve the flow of the music.

Figure 5

Liberty Fanfare, excerpt from the published arrangement.17

There are even rare instances where a published piano piece includes a sort of ossia line, or third staff of music, which cannot be played simultaneously, yet cannot be used as a substitute for any other line. Such is the case of the most non-idiomatic arrangement of all, the season 2 main title of Land of the Giants (ABC, 1969–1970), arguably a sketch score more than an actual piano arrangement (despite being published in a piano anthology). In the Fanfare for Michael Dukakis, the entire middle section expands the piano score to three staves, giving us a glimpse of the exciting countermelody of this unrecorded miniature masterpiece (Figure 6). We could read such passages as instances of what Peter Szendy identified in Liszt’s versions of Beethoven’s symphonies as “the inscription of the absence of or desire for the original in the hollow of the transcription,” which “create[s] longing […] for its many instruments” ([2001] 2008, 57), or else as what Jonathan Kregor more succinctly refers to as a “multi-perspectival reading of the piece” that “remains an open work” (2010, 33).

Figure 6

Fanfare for Michael Dukakis, excerpt from the published arrangement.

Even if these technical (and conceptual) difficulties are not the norm, they happen frequently enough to disprove the kind of oft-repeated generalization that arrangements reduce the work “to the slight minimum” (as quoted above). They also attest to the varying approaches that arrangers have adopted throughout the years. As a result, navigating this repertoire to find an adequate arrangement can be challenging for both intermediate and advanced pianists. But a lack of standard quality or difficulty should not prompt musicians to dismiss the entire repertoire as trivial. At best, piano arrangements are artfully made, and can be exciting pieces to perform. However, like many nineteenth-century arrangements of orchestral works, their suitability for public performance is not unambiguous, and the distinction between music destined for private enjoyment or for the concert hall remains a disputed matter.

The performance of film music in concert has attracted some scholarly attention lately, but articles on the topic always assume that the music is performed by orchestral forces. If piano arrangements are mentioned at all, it is to exclude them (see, for instance, Lehman 2018, 21).18 Otherwise, the assumed limited purpose of piano arrangements in the musical landscape is clearly stated. When Emilio Audissino introduces the three “main manifestations of the external life of film music,” he opposes “piano reductions for home performance” from “adaptations for concert performance” (the third type being “disc records”). He thus clearly delineates the divide between private and public settings that nineteenth-century musicians were familiar with, as well as the distinction between the somewhat diminutive term of reduction versus the more proper adaptation (Audissino 2021, 10). Yet, scholars are not to blame for dismissing a type of concert that remains extremely rare, in large part due to the limited availability of adequate and reliable material for solo performance, as I have shown above. There is no denying that, despite some noteworthy exceptions, the difficulty level of most available publications is not high enough for professional musicians. Thus, apart from a few student recitals and YouTube videos, professional musicians have ignored these arrangements, preferring instead to create and record their own versions. The recordings mentioned in this article’s introduction all include new and unique arrangements, except for about half of the album by Simone Pedroni, to which I will return below.

Over the years, only one piano publication explicitly attempted to bring John Williams’s music to the concert stage. The Star Wars: Suite for Piano, arranged by Tony Esposito, was the second volume in the Classic Film Scores series from Warner Brothers Publications, which issued fifteen suites between 1986 and 1990, two-thirds of which were for scores by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, and John Williams.19 In a foreword, Jeff Sultanof, one of the series’ arrangers, explained the double purpose of this series: “We felt that if there was a large public that loved to hear film scores, then there must be many musicians who want to play and study them. […] We are finding that, in addition to learning these arrangements, pianists are programming them for recitals” (Sultanof 1989). The back cover of each volume reiterated that it was “perfect for study and concert performances.” On the front cover, a facsimile of the first page of the orchestral score unified the series with a more serious and refined design, which seemed to promise that each book offered a faithful rendition of the music, indeed suitable for both study and concert, and thus at a safe distance from movie memorabilia.

The Star Wars: Suite for Piano comprises five of the seven movements included in the Symphonic Suite originally published by Fox Fanfare Music in the months following the film’s release. The first three movements are faithful transcriptions of the original album’s “Main Title” (similar to the standard concert version that includes the end credit material and incorporates “Princess Leia’s Theme”), “Princess Leia’s Theme,” and “Cantina Band.” The music is technically difficult, but highly rewarding to perform. The fourth movement, “The Battle,” adopts a different strategy. Instead of presenting a full album track, it attempts to merge together snippets of several action cues in order to retell the movie’s third act inside the Death Star, from the tense “Inner City” all the way to the pounding and victorious finale of the “Battle of Yavin.”20 The result is both musically and technically awkward: contrasts of tempos, registers, and textures abound without building up musical tension, the famous “Here They Come” section is absent, and a long passage is made up of repetitive étude-like chromatic scales that may work in the film’s context, but not in a piano solo version (Figure 7). This movement alone supports Christensen’s statement that “not even the most creative arrangers could make some compositions sound good on the keyboard” (1999, 272). The last movement, “The Throne Room and End Title,” is more satisfactory but relies too heavily on wide chords in the left hand (spanning up to two octaves!) that disrupt the flow of the march.

Figure 7

Excerpt from the “The Battle”, the fourth movement of Tony Esposito’s Star Wars: Suite for Piano. This pattern spans a total of 33 measures, more than two full pages.

Despite some surprisingly effective arrangements in its earlier movements, this suite—like all others in the Classic Film Scores series—failed to attract professional performers. It simply became another instance of domestic music-making, albeit a more advanced one. Nonetheless, it was a laudable attempt at creating a concert suite of a high pianistic level that could be as faithful to the orchestral score as possible.21

Concerns about the public performance of arrangements—even those of the highest quality—were already vividly highlighted by Robert Schumann in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik of April 10, 1840, when he reacted to a performance of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony by Liszt:

When performed at home in an intimate atmosphere, it is possible to forget the otherwise masterly and conscientiously made transcription from the orchestra. But in a large concert hall, in the same place where we have so often heard the symphony played perfectly by an orchestra, the lack of instrumentation stands out perceptibly, all the more so when the transcription vainly attempts to convey the orchestral mass in its full strength. A simpler arrangement, a mere intimation, would perhaps have far greater effect. (translated by Christensen 1999, 289)

In short, Schumann suggests that it is not the most accurate, faithful, or technically difficult arrangements that work best in concert, since they remind us of the orchestra’s absence. This idea is echoed by some contemporary pianists who renounce trying to match the orchestral score, like Dan Redfeld, who explains: “It’s difficult to translate [John Williams’s] counterpoint on the piano and also capture all that color on one instrument. So it’s distilling it down to the basic melody we hear as an audience, and then filling in to get some approximation of the counter-line or harmonies.” (quoted in Larson 2016)22

A good example of this simpler approach is found in the folios for Lincoln (Steven Spielberg, 2012) and The Book Thief (Brian Percival, 2013), coincidentally the only folios with arrangements credited to John Williams himself. The music does not attempt to precisely match the album tracks: it is reduced to its essential components and is idiomatic of Williams’s late piano writing, which also occupies a prominent place in these scores. Simone Pedroni compares them to Prokofiev’s piano version of Romeo and Juliet, saying: “It’s an essential, almost austere writing, like a pencil drawing that however reveals the essential truth on which the orchestral version is based” (Caschetto 2018, 412). Pedroni’s album, John Williams: Themes and Transcriptions for Piano, includes recordings of these two folios mostly as published. It was a revelation for many reviewers, one of whom wrote that “these familiar scores performed by solo piano reveal a clarity and simple purity often lost in a full orchestral reading” (Siegel 2017).23 I believe a case could be made to consider these two folios as actual “works” by John Williams rather than as “mere” arrangements (after all, Prokofiev gave separate opus numbers to his transcriptions of pieces from Romeo and Juliet and Cinderella).24 They further challenge the view that piano arrangements of film music must be both technically difficult and faithful to the orchestral brilliance to have any merit in concert—and hence they confirm Schumann’s advice. If we are willing to be “amazed”, like pianist Dan Redfeld, by the simplicity of John Williams’s own piano writing, perhaps we can reconsider how we approach and evaluate other piano arrangements of his music.

Conclusion

In this article, I signalled multiple reasons that could deter scholars, professionals, and even amateur musicians from taking these publications seriously, despite the popularity of film music concerts and piano arrangements of film music. The regular inclusion of several pages of illustrations can very well attract movie fans but might as well deter other pianists used to the sober design of classical music publications, which usually ensures quality, regardless of level. The frequent errors reveal a lack of attention to detail, corners cut short to meet tight release schedules. Older or less familiar titles have long been out of print (and remain unavailable even on digital platforms), drastically reducing the diversity of music one can hope to perform or study. To avoid these shortcomings, pianists—in concerts, but especially online—usually perform their own rewritings of their favorite film themes, largely independently from the print and digital markets for sheet music. Hence, there is a noticeable gap between the material that musicians perform (or find worthy of performance) and the material that is available publicly to those who do not necessarily have the skills or the time to create their own arrangements of John Williams’s music.

To respond to these various issues, we must start by reassessing the value and functions of piano arrangements of film music. After all, they have been part of publishers’ catalogues for over a hundred years. The sheer number of publications is evidence of their lasting impact on musicians in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and confirms the need for scholars to look at recent and current repertoires in their examinations of this practice. In her study of the arrangements of Beethoven’s symphonies, Nancy November wrote that “chamber arrangements of large-scale works were so prevalent in the nineteenth century that to ignore them, as has often been done, is to miss an essential part of the reception or ‘life history’ of the works in question” (November 2021, 3). The same could be said of John Williams’s works. For the past sixty years, countless people have engaged with his music outside of the movies, soundtrack albums, or orchestral concerts. Despite their shortcomings, piano arrangements have allowed musicians to appreciate film music with a hands-on approach and to get to explore the works from the inside, or else to simply hear new takes on familiar themes. These alternate ways of engaging with John Williams’s music, despite all their intricacies and complexities, deserve to be taken into account when studying the broader reception of his work.