Steven Spielberg’s 2001 film A.I. Artificial Intelligence is a futuristic reworking of the Pinocchio story that substitutes a robot boy (David) for the wooden puppet as the protagonist1. David is given advanced artificial intelligence that enables him to love, but this causes him endless conflict in a human world. While the conflict is present from his very first appearance, the “Hide and Seek” scene is an important turning point as it shows the first suggestion that his adopted mother Monica is starting to accept him. The film overall addresses complex themes about humanity, love, and creation, and the conflicts these themes create between orga (humans) and mecha (lifelike, human-created robots), and one of the most important factors in this exploration is the score composed by John Williams. A comprehensive analysis, focused on harmony, rhythm, orchestration, and leitmotifs, of his score to the “Hide and Seek” scene reveals this exploration in the interplay between the “Curiosity” theme and the “Bonding” theme. The usage of electronics along with ever-growing acoustic accompaniments further demonstrate Monica’s orga acceptance of the mecha David. However, the subtle complexities and various interruptions scattered throughout the cue indicate Monica’s uncertainty.

Signifier Dichotomy

Because the score explores the dichotomy of orga and mecha elements in the film, this paper uses a methodology that differentiates between musical representations of orga and mecha. The following table (Table 1) shows the main signifiers and their counterparts that I have explored in my research for the entire A.I. film, with orga signifiers relating to a general “Late-Romantic style,” while mecha signifiers exhibit an avoidance of that Romantic style. One finds the usage of lyrical melody with long, sustained phrases for orga subjects, while its mecha counterpart overtly uses repetition, including minimalism. Acoustic instrumentation often signifies orga subjects, while electronic instrumentation is reserved for mecha subjects. The usage of Khachaturian’s “Adagio” and Ligeti’s micropolyphony will not be discussed in this paper because they play no role in the specific scene to be discussed later, but is prominent throughout the rest of the score, therefore is worth including in the table.

Table 1

|

Orga Signifiers Late-Romantic style |

Mecha Signifiers Avoidance of Romanticism |

| Lyrical melody with long, sustained phrases | Overt use of repetition, including minimalism |

| Khachaturian’s “Adagio” (from Spartacus [Спартак]) | Ligeti’s micropolyphony |

| Acoustic instrumentation | Electronic instrumentation |

Signifier Dichotomy in A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

The late-Romantic style associated with Wagner and Strauss has been a primary influence on film music composers since Golden Age Hollywood, despite the style’s being “several decades out of date in the concert hall” (Cooke 2008, 78). Several reasons for this association have been offered including the immigration of European composers at that time (Cooke 2008, 78), the studios’ assumption that “the public would refuse to tolerate any music more modern-sounding than a Liszt symphonic poem” (Palmer 1990, 25), and film scoring’s connection to opera. Prendergast writes, “When confronted with the kind of dramatic problems films presented to them, Steiner, Korngold, and Newman merely looked […] to those composers who had, for the most part, solved almost identical problems in their operas” (Prendergast [1977] 1992, 39). Christopher Palmer presents the connection as a product of musical escapism, with the marriage of such anachronistic music to modern story-telling stemming from Hollywood functioning as a “dream factory” and Romanticism being the music of fantasy, dream, and illusion (Palmer 2008, 23).

Caryl Flinn suggests the tradition of using Romantic styles in film music has to do with a “utopian function,” or “an impression of perfection and integrity in an otherwise imperfect, unintegrated world,” and that “has been assigned to […] film music of the 1930s and 1940s in particular” (1992, 9). This music supplies something missing as “a result of a fundamental ontological deficiency of the cinema” (Flinn 1992, 44), or as Herrmann suggests, “a piece of film, by its nature, lacks a certain ability to convey emotional overtones” (Herrmann, quoted in Manvel 1957, 244). Susan McClary critiques this relationship, stating, “Romanticism also offered spectators a means of escape into a mythologized and culturally elite past” (2007, 50).

Williams’s connection to this Romantic style is deeply rooted in his own work. His main model for the music to Star Wars, the score that ushered in a “Modern” Hollywood Style, was the prominent Golden Age composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold (Audissino 2014, 72). Using Palmer’s, Flinn’s, and McClary’s critiques of this association, this paper examines the usage of Romantic influences in this score as critical signifiers of “human” concepts, ranging from emotions to failures and shortcomings to the “utopian” function of David’s need to be loved.

The usage of leitmotif in film comes from the same late-Romantic operatic tradition of Wagner and Strauss that Prendergast discussed before. Adorno critiques the early usage of leitmotif in film music when he says the sole function “is to announce heroes and situations so as to help the audience to orient itself more easily” (Adorno 1989, 36). In Buhler’s article “Star Wars, Music, and Myth,” he counters Adorno’s notion with John Williams’s use of leitmotifs in the original Star Wars trilogy “com[ing] as close as any film music to the tone of Wagner” (2000, 44), whose primary purpose “is the production of myth not signification” (2000, 43). This is important when looking at the usage of themes as leitmotifs in A.I. because themes are sometimes brought back in situations in which the obvious signification makes little sense.

Another signifier for orga subjects in this score is Williams’s use of lyrical melodies with long, sustained phrases. As demonstrated by Stefani, melody is a difficult term to define, but he proposes “‘melody’ is a notion belonging essentially to everyday culture, to popular culture” (1987, 21). In other words, its recognition stems from a gathered human experience. Stefani often uses the word “singable” in his exploration for a definition of melody. According to Rowell, Wagner viewed melody as being able to “articulate expressions of inarticulate human feeling” (2004, 28). One of the many elements Williams utilizes in the score to A.I. is lyrical melody with long, sustained phrases, an approach to melody often associated with Romantic music (Szabolcsi 1970, 278). These are in direct contrast with the other elements such as minimalism and repetitive phrasing that feature so prominently in the score. Furthermore, the melodies are mostly associated with situations in the film relating to Monica, an orga subject.

Acoustic instrumentation, more specifically the usage of traditional orchestral elements, being a signifier of orga has roots in the overall history of film scoring, as well as in Williams’s previous scores. From the earliest days of film scoring, the symphony orchestra played an integral role. Much of the music came from the late-romantic tradition, and the predominant medium of expression was the orchestra. Kalinak notes that over the decades numerous challenges to the classical orchestra in film music developed, such as jazz, rock, pop, synthesizers, etc. (1992, 185–188). Despite these challenges, the traditional orchestra continued “to function in Hollywood as a primary determinant on the construction of the film score” (Kalinak 1992, 188). In his score for Star Wars: Episode V – Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980), Williams used the orchestra because “music should have a familiar emotional ring so that as you looked at these strange robots and other unearthly creatures, at sights hitherto unseen, the music would be rooted in familiar traditions” (Williams, quoted in Arnold 1980, 265). Similarly, in the case of A.I., Williams is able to focus the audience on orga elements through the usage of the familiar sounds of the traditional, acoustic orchestra.

If late-Romantic associations signify orga elements, then the conspicuous use of styles and techniques not related to those found in late-Romantic music signifies mecha elements. Rebecca Eaton notes that the use of minimalism to signify the mechanical is common, and this association can be traced back to early reviews of minimalist works in the 70s (2014, 5). She lists dozens of examples of multimedia works that all use minimalism in conjunction with machines or technology, including Glass’ score to Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982), an Audi commercial whose music was so close to Glass stylistically that a lawsuit ensued (1996), and Williams’s score to A.I. Her reasoning for this connection is that minimalism “features a regular, steady pulse. It is not melodically based, but repetition-based. It typically displays limited dynamic contrast. All of these musical attributes are also characteristics of the working of machines, be they manifested in sound, visually observed motion, or internal process” (Eaton 2014, 5). This is in direct contrast with the Romantic idiom signifying human emotion. For instance, in cues dominated by minimalism, the emotion from the scene is controlled by Romantic procedures such as varying the dynamic range, expanding the range of the instruments, and frequent harmonic shifts, as is the case with the “Abandoned in the Woods” cue. This paper, in line with Eaton’s analysis, concludes that the usage of minimalism is customarily a signifier of the mecha.

I further this notion to include several examples of conspicuous repetition on larger structural levels. For instance, while minimalism generally features a repeated pattern of just a few notes or measures, A.I. features examples of phrase and structural repetitions that are sometimes separated by several dozen measures. Arved Ashby discusses how the mechanical repetition in the context of recorded music changes the way we form musical memories since the listener is able to hear an exact replica of a given piece of music countless times (Ashby 2010, 62). While not as immediately obvious as repetitions of specific phrases/gestures (e.g. a four-note chordal arpeggio repeated twenty times in a row), these higher-level repetitions are still easily recognizable, and in the case of A.I. usually come in conflict with orga music such as lyrical melodies.

One obvious way music can evoke artificiality is through the use of electronics or synthesizers. Williams is mainly known for his orchestral scores, however, he himself has used synthesizers on several notable occasions, including a pivotal moment in Empire Strikes Back when Luke Skywalker ventures off to the Magic Tree to face his greatest fears, along with films depicting such inhuman acts as murder and rape, such as Presumed Innocent (Alan J. Pakula, 1990), Sleepers (Barry Levinson, 1996), and Munich (Steven Spielberg, 2005). Interestingly, the example that best matches his usage of electronics in A.I. actually comes from the lesser-known film Heartbeeps (Allan Arkush, 1981) in which Williams uses a plethora of electronic sounds, in combination with the usual orchestra, to underscore the love story between two robots.

Because these signifiers are not always black and white in the score and often blend into each other, making a definitive statement is sometimes difficult. For instance, in the “Escape from Rouge City” cue, a pervasive minimalist style runs throughout, however it is scored with a large, Romantic-sized orchestra with little to no electronics. I will explore these issues and how their very existence augments Williams’s musical exploration of the orga vs. the mecha.

The link between the music and the content of A.I. is paramount, therefore my analyses and reductions/transcriptions are based on the soundtrack found on the 2002 Dreamworks Video DVD release. For his soundtracks, Williams records separate cues specifically written for the album and “tries to arrange the tracks in a more interesting way than just in the order they are heard in the film” (Kenneth Wannberg, quoted in Thaxton n.d.). Because of this rearranging, soundtracks often differ from the material found in the final cut of the film. Even the cues written for the film are sometimes edited and rearranged after recording so the written score does not coincide with the music as heard in the finished film. Any discrepancies between the music as presented in this paper and the music found on the original soundtrack album or the final versions of the scores as prepared by Conrad Pope and John Neufeld will be due to changes made during the post-recording editing process. Because film music is a collaborative effort between the filmmaker and the composer, it is important to analyze the music in its final form.

“Hide and Seek”

The “Hide and Seek” scene is an important turning point in the film because it shows the first time Monica bonds with David. However, it never eschews the conflict between the two characters and within Monica herself. In order for her to imprint him, she needs to bond with him and accept him as part of the family. Up to this point in the film, the only interactions between them are 1) her introduction to him, a confusing moment that ultimately led to a small argument with her husband Henry, and 2) her awkward response to him asking her to dress him, abruptly leaving him alone in the room with Henry. This scene shows the beginnings of Monica’s acceptance of David, albeit minimal and still surrounded by doubt and discomfort. Williams’s music for the scene shows this gradual bond with his mixing of two primary themes, “Curiosity” and “Bonding,” along with the mixing of both mecha and orga signifiers, while also suggesting the underlying conflicts.

This scene also marks the beginning of an important musical transition from Monica’s point-of-view to David’s. Up to this point in the film, the score has supported Monica’s emotional state. The melancholy strings of the Khachaturian-esque “Cryogenics” theme capture the loneliness and sorrow of Monica as she futilely reads to her frozen biological son. When Monica is first introduced to David, the music moves through several distinct moods from the eerie, high electronics when she’s unsure of him at their first meeting, to the warmer, but harmonically unsettled strings for Monica and Henry’s argument, to the lyrical English horn solo when she starts to reconsider. These shifting musical moods match Monica’s own emotional uncertainty.

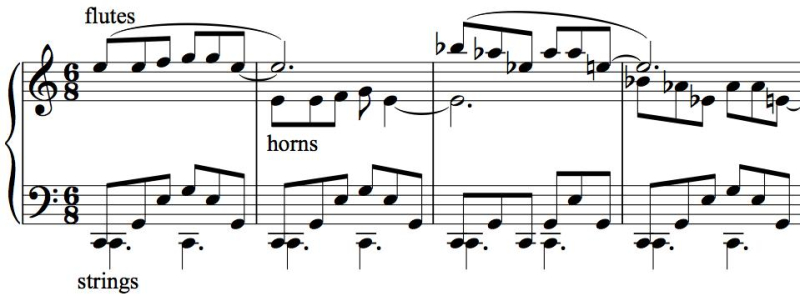

The “Hide and Seek” scene is the first time the score offers hints at David’s perspective. The scene starts with a shot of David peeking over the edge of the table, making him look almost alien-like (15:34). He stares intently at the pouring of the coffee. Right from the beginning, Williams establishes two of the most important stylistic components of the whole cue: a persistent dotted quarter C drone in the pizzicato strings, and a repetitive figure in the harp consisting of wide leaps both ascending and descending, a precursor to the “Curiosity” theme (Figure 1). These are important because the C drone sets up what will ultimately be the near-constant devotion to the tonality of C, effectively devoid of any modulation over the course of three minutes.2 With this the persistent harp figure introduces the idea of repetition that is so prominent throughout. While Monica is present, for the first time in the film, the music supports David’s experience.

Figure 1

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Curiosity” theme precursor.

All musical reductions were created by Stefan Swanson from music as presented in the 2002 DreamWorks Home Entertainment DVD release of the film.

The music does not however leave Monica’s perspective for long. After four repetitions of the harp figure, the “Curiosity” theme is stated in a bell-like electronic sound with a tinny, artificial attack that contrasts greatly with the softer, warmer sustained notes of the surrounding acoustic instruments (Figure 2). The first two notes of the motive, C and D, coincide with the established C tonic. The next five notes, F♯, G♯, B, G♯ and D♯, break from that and suggest the key of E major, B major, or even A Lydian, creating what Royal Brown refers to as a “mildly unsettling bitonality” in his analysis of this scene (Brown 2001, 330). Underneath the repeating motive, the strings never waver from their Lydian infused C Major chord. Already two seemingly clashing ideas, a “standing one’s ground” tonic in C and an unrelated key with at least four accidentals, are simultaneously evident in the music. This might be David’s first major experience, as presented in the film, but Monica has not warmed to him and his presence is noticeably clashing with her sensibilities.

Figure 2

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Curiosity” theme.

The “Curiosity” theme throughout the film is notable for its lack of evolution. The first statement is in the Introduction to David when Monica and Henry are discussing David. Despite her obvious reservations about the situation, Monica is somewhat taken by David’s realism. Henry notes that although he seems real, David is in fact a mecha child (12:22) and the “Curiosity” theme is heard repeated three times as the camera lingers on Monica’s confused face. The music serves the dual purpose of reminding the audience that David is artificial and hinting that Monica herself is curious about the potential of adopting David. After the “Hide and Seek” scene, the only other instance of the theme is in the Perfume scene, when David first notices Monica’s favorite, and scarce, perfume (25:08). When he sees this is her favorite fragrance, he puts the rest of the bottle on himself, erroneously thinking this will make her happy. The theme’s usage here reinforces David’s inability to fit in with the humans, despite his best efforts. What is notable about all of these instances, including those in the “Hide and Seek” scene, is the similarity between them. The theme never grows or develops. Each statement is voiced in the same bell-like electronic sound in the same register and always repeats at least once, matching David’s lack of “human” understanding.

The “Hide and Seek” cue initially focuses on the discord between Monica and David, but the music eventually offers hints at Monica’s gradual acceptance of him. While other material is introduced and developed (most notably the “Bonding” theme, which will be discussed shortly), the “Curiosity” theme constantly reappears in two to four literal repetitions, never varying or developing. Each time the “Curiosity” theme is presented, the orchestral accompaniment rises in prominence, as if the music is following Monica’s orga approval of the mecha David. As the table shows, what starts out as a simple quiet string tremolo accompaniment of the first statement, gradually adds instruments, reaching its zenith by the fourth statement with a fuller complement of winds, harp, and piano along with more active string figures. While the fifth statement reduces down to a similar level as the first statement, this is only a temporary pause in the pattern to set up the dramatic sixth and final statement that reaches a similar height as the fourth statement. Because the “Curiosity” theme is always voiced in the same electronic sound, the constantly changing and growing accompaniment grab the attention and mirror Monica’s drama unfolding on the screen. The scene starts with the unsettling appearance of David while she drinks coffee and progresses to them actually playing a game together.

Table 2

|

Statement |

Accompaniment |

| 1 |

– quiet violin, viola, cello tremolo chords – light bass pizzicato |

| 2 |

– quiet violin, viola, cello tremolo chords – more prominent bass pizzicato – harp accents |

| 3* |

– violin, viola tremolo chords – arpeggiated cello line – bass pizzicato drone – horns play a new melody |

| 4 |

– active violin flourishes – arpeggiated cello line – arco bass drone – harp accents – piano accents – bassoon drones |

| 5 |

– quiet violin tremolo chords – viola pizzicato figure (doubled with harp) – clarinet flourish |

| 6 |

– active violin flourishes – arpeggiated cello line – arco bass drone – harp glissandi – piano accents |

Changing orchestration.

* “Curiosity” theme becomes a counter theme to the “Bonding” theme.

Along with the changing orchestration, Monica’s bonding with David is also expressed through Williams’s usage of the “Bonding” theme, however this theme suggests the bonding is more complicated than her simply progressing from “not accepting” to “accepting.” The theme itself starts firmly in C major but soon hints at bitonality with the B♭, A♭, and E♭ in the third measure (also the A♭ and B♭ in the fifth measure) over the continuing C major accompaniment, eventually settling back into C major. While the orchestration of flute and horn melody over C major triads in strings is warm and comforting, the deviations from C major in the theme show the underlying complexity of Monica’s feelings toward this interaction with David.

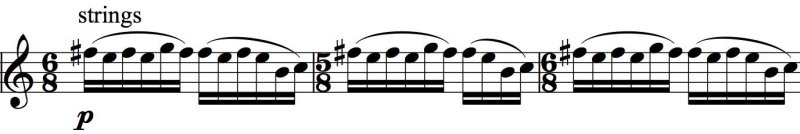

Even the music that often leads into the “Bonding” theme, acting as its “precursor,” has a mix of elements that similarly suggest Monica’s internal conflict. Played entirely on piano, it contains a simple, tonal melody that is firmly entrenched in C major, accompanied by a repeated middle C drone (Figure 3). While the melodic rhythm is comprised of only eighth notes, it dances between 6/8 and 5/8 meters, giving a subtly disjointed feel to the rhythm. Also of note is how the intervallic size gradually increases as the melody moves forward. The music is simultaneously grounded and disjointed.

Figure 3

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Curiosity” theme precursor.

Similarly to the development of the accompaniment to the “Curiosity” theme, the development of the “Bonding” theme over the course of the cue shows the growth of Monica’s acceptance to David. Its first statement occurs when David appears while Monica is making the bed (16:34). Although she is mildly surprised, David is wearing a bright smile. This is also the first time the “Curiosity” theme is interwoven into the “Bonding” theme as a counter theme (Figure 4), showing how Monica’s orga world and David’s mecha world are starting to come together.

Figure 4

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Curiosity” theme with “Bonding” theme.

The second statement occurs just before David playfully blocks Monica’s way in an attempt to initiate a game with her. The accompanying string C major triad figures return, but the theme is now featured in flutes with a repeated response in horns (Figure 5), removing the “Curiosity” theme interruption. The “Bonding” theme has now nearly rid itself of the mecha elements, the electronics and the bitonality of the “Curiosity” theme, although the B♭, A♭, and E♭ still occur in the theme itself, perhaps suggesting the “artificiality” never fully disappears.

Figure 5

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Bonding” theme alone.

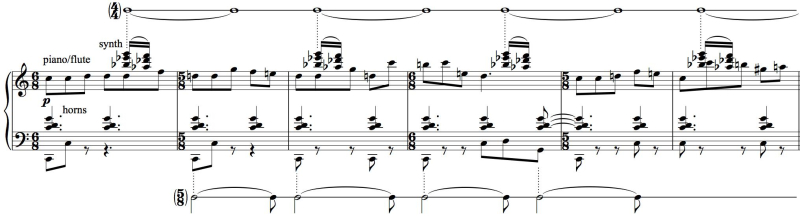

The final statement of the “Bonding” theme is similar to the last statement, but now with full woodwinds, including bassoons, carrying the melody while the horns answer imitatively again (Figure 6). Monica is now watching David in his room (17:55). Although she walks away and seems annoyed at her own inability to decide whether she has fully accepted David, the music, with its minimizing of electronic elements and fullest acoustic orchestration yet, suggests this is the warmest she has felt about him so far.

Figure 6

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Bonding” theme final statement.

The playfulness, the optimism, and the gradual phasing out of the mecha musical elements certainly suggest Monica’s developing acceptance, but the final sequence in the scene punctuates it with uncertainty. The violins play a steady sixteenth note pattern on the close up of the door handle turning (18:10; Figure 7). The repetitiveness of the pattern clues the audience into who is opening the door. Indeed it turns out to be David, surprising Monica as she sits on the toilet, and with a noticeably cold smile he says, “I found you,” (18:17). Although the music does not take a conspicuously dark turn, it devolves into simple eighth note C’s repeated in the vibraphone (Figure 8).

Figure 7

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, string flourish (18:10).

Figure 8

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, repeated Cs (18:17).

Interruptions play a significant role in this scene both on the screen and in the music. David’s robotic nature has little regard or understanding for human habits and etiquette. The scene includes five instances of David interrupting Monica and although the score plays most of them, it also offers its own interruptions, sometimes unrelated to the visual. In the first instance of the piano “precursor” figure to the “Bonding” theme (see Figure 1), the piano plays what sounds like the consequent phrase but is abruptly cut off by the “Curiosity” theme before it can finish. This accompanies David’s sudden appearance to Monica when she’s drinking her coffee (16:09).

Williams even employs a recurring motive that acts as a musical “reset button” to stop a certain passage in its tracks and allow for an often unrelated passage to take over. The first instance of this can be found when David studies Monica’s cup of coffee. The “precursor” to the “Bonding” theme plays two uninterrupted phrases, but just as it is about to conclude itself it breaks down harmonically and is interrupted by this “reset” motive (Figure 9), allowing the “Curiosity” theme to take over. This motive, that explicitly occurs four times, is yet another way the music shows the robotic essence of David by breaking down and never resolving as he never actually figures out the meaning of the coffee.

Figure 9

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Reset” motive.

A subtler interruption can be found just before the first statement of the “Bonding” theme. Up to that point, there have been two occurrences of the “Curiosity” theme and each time the theme is stated four times. In this third occurrence, the theme is only stated twice before it is interrupted by the “reset” motive and followed by the “Bonding” theme. Interestingly, the “missing” two instances of the “Curiosity” theme are found just a few measures later as the counter theme to the “Bonding” theme. Despite Monica’s warming attitude, David is still an awkward interruption in her life at this point.

A notable interruption in the rhythm/meter/key occurs after Monica opens the closet door to let David out (17:34). The music starts with the ‘precursor’ to the “Bonding” theme but is soon interfered with by a recurring, two sixteenth note figure in electronics with almost no relation to the underlying music. Harmonically this figure, an E♭ triad to D♭ triad in quick succession, has no relation to C major. It also occurs in a register not occupied by any other voice. Finally, this figure, rhythmically speaking, operates on a separate Roederian pulse stream from the rest of the music (Figure 10) (Roeder 2004, 45). The 6/8 to 5/8 back and forth along with the unexpected accents (the melodic peaks and the horn attacks) give the music an unsteady pulse. However, the figure in electronics operates on a regular pulse stream that has no relation to meter or pulse of the rest of the music. All of these aspects draw a great deal of attention to this little figure, emphasizing that once again David’s artificiality is still on Monica’s mind.

Figure 10

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Roederian pulse stream (17:34).

Conclusion

The film A.I. Artificial Intelligence is filled with complex ideas such as love, human connection, and the ethical implications of actions taken against artificial beings, that are not always answered or resolved. The ending exemplifies this as “David’s Oedipal fixation remains utterly static throughout two thousand years, in spite of the fact that no human being—including his mother—ever shows him any reciprocal affection. The fact that his devotion is fixed, helpless, and arbitrary ultimately makes his heroism empty and the happy ending hollow” (Kreider 2002, 33–34). Even the fate of Gigolo Joe, who was last seen being slowly drawn away from David towards the police aircraft, is never revealed to the audience, despite his being David’s closest companion throughout the film.

Williams’s score helps drive this as the music draws from a wide variety of influences and styles, from the Khachaturian “Adagio,” to Ligeti’s micropolyphony, to minimalism, even to a techno/rock hybrid. All of these various styles help explore the subjects of orga and mecha in the film, and moreover how those subjects separate from each other and come together. From these subjects come the musical signifiers this paper uses to explore each theme and scene.

Right from the beginning of the film, the music evokes orga with the loneliness of the Khachaturian-esque “Cryogenics” theme. As the film progresses this theme absorbs the Ligeti-esque influences in the “Other Davids / Suicide” scene and transforms into a mix of signifiers that sets up the ambiguity of the final act. Other scenes such as “Hide and Seek” also combine the signifiers but in more humorously jarring ways to show the development of the orga Monica’s acceptance of the mecha David. Even melody, designated as one of the orga signifiers, is blended with more subtle mecha signifiers such as large-scale repetition. Just as further exploration of the film itself can reveal deeper meanings that sometimes break from the initial interpretation, so too does Williams’s score.

Over the course of the entire “Hide and Seek” cue, there seems to be a battle between the “Curiosity” and “Bonding” themes. At times the two themes try to connect with each other, but they always remain in conflict. Even the form itself, a mix of elements of a Rondo with blocked sections, suggests that although Monica is beginning to see David in a new light, she is still constantly wavering back and forth. In just a few minutes of music, this cue has outlined the growth of Monica’s feelings toward David from near revulsion to genuine interest, along with showing how his artificiality is still both present and potentially detrimental to their relationship.

Ultimately, Monica’s curiosity gets the best of her. Despite the “Curiosity” theme being associated with David’s mecha curiosity, it is hers that starts them both on a path leading to her imprinting David and eventually abandoning him in the woods. Williams’s score gives the audience the appropriate warmth on the surface but never allows the listener to forget the underlying conflict present in the drama. The use of leitmotifs in this cue goes deeper than Adorno’s notion that the main purpose of the Hollywood leitmotif is to “help the audience to orient itself more easily” (Adorno 1989, 36). If anything the usage here disorients the audience as the deeper relationships between the characters are slowly revealed. This scene is the turning point in Monica and David’s relationship and Williams’s intricately planned cue lets the audience in on its darker secrets.