Introduction

Among the various approaches that can be used to investigate specialized languages, discourse and genre analyses provide interesting insight into the specialization of discourse communities and their practices, taking into account linguistic and extralinguistic features. In his presentation of the chronological and gradual development of written discourse analysis, V. K. Bhatia (2004: 12) identifies three main successive but complementary and overlapping phases that highlight major concerns in discourse analysis: textualization, organization and contextualization. In the 1960s and 1970s, discourse analyses were mainly influenced by formal linguistics and focused on the lexicogrammatical and syntactic features of discourse productions (Barber, 1962; Halliday et al., 1964; Spencer, 1975). In the 1980s and early 1990s, extensive attention was then given to the internal organization of genres, with a specific emphasis on rhetorical structures, patterns and moves within specialized texts (Miller, 1984; Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993). Starting in the 1990s, the third phase extended the analysis beyond the textual dimension and incorporated the disciplinary and social contexts of discourse practices, shedding light on the sociocognitive and pragmatic features of genres (Bhatia, 1993; Bazerman, 1994; Hyland, 2000). These different approaches show that discourse, defined as language in use (Neveu, 2004: 105), is a complex and multifaceted object of study. When studying specialized discursive practices, and especially specialized genres,

[t]he analyst takes on the role of detective, in order to unravel the mysteries of the artifact under consideration and to emphasize the importance of motive as a clue to the nature of that artifact, thus introducing a kind of excitement rarely experienced in other approaches to linguistic analysis (Bhatia, 1993: xiii).

The present paper adopts this perspective in order to investigate discourse practices of British and American police officers, with a specific focus on discourse genres. This article does not aim at adopting a contrastive perspective on the British and American varieties of English for Police Purposes, but rather at drawing on examples from both cultural contexts in order to illustrate discourse interrelations at work in this specialized language.

In the literature exploring English for Police Purposes – and police discourse in particular – studies tend to focus on specialized communication and practices as well as on major police discourse genres. They analyze caution and Miranda warnings (Rock, 2007; Heydon, 2013), police calls (Tracy and Anderson, 1999; Rock, 2018), police reports (Coulthard, 2002), police humor (Holdaway, 1988; Gayadeen and Phillips, 2016; Cartron, 2023b), suspect interviews (Leo, 1996; Magid, 2001; Haworth, 2006; Benneworth, 2009; Cartron, 2023a), victim and witness interviews (Rock, 2001; Milne and Bull, 2006), interactions with professionals of related specialized fields (Johnson, 2003; Charman, 2013), and “policespeak” (Fox, 1993; Johnson et al., 1993; Hall, 2008). In order to investigate interfaces at work in police discourse, this article draws on the results of a detailed analysis of authentic productions from British and American police officers (Cartron, 2022). It also examines several sources, including emergency calls to the police, court case files, police reports and suspect/victim interviews related to various cases (aggravated child abuse, discovery of dead bodies, indecent exposure/bestiality and theft). Qualitative as well as quantitative methods were used to investigate the multiple facets of these specialized genres1. In addition, interviews were conducted with eleven British and five American police officers. Several topics were addressed, including frequently used police discursive genres, conventions regulating discursive practices, language registers, communicative events in which they participate, as well as frequent interlocutors.

English for Police Purposes is a specialized variety of English characterized by various genres, both spoken – such as police interviews, radio communications or court testimonies – and written genres – police reports, manuals or codes of ethics, for instance. Although different in terms of linguistic features, internal organization, context of production or intended audience, these different genres are closely interrelated, as they all serve a common “specialized collective intentionality” (Van der Yeught, 2019: 65) shared by the members of the discourse community. In other words, discourse genres are used by police officers in order to reach and fulfill a set of common professional goals, that can be outlined as follows: maintaining public order, preventing and punishing breaches of the law and protecting individuals and property. Discourse productions are “specialized” because they are produced by law enforcement officers while carrying out their duties in order to serve various specialized purposes. The first section of this paper presents an overview and a typology of police productions, shedding light on the different professional purposes they serve. The article then focuses on another salient characteristic, exploring the network of related texts – both spoken and written – produced by police officers at the different stages of the investigation. Finally, it explores the constellations of communicative events as well as the discourse modelling process and the textual travels that occur at the different and successive steps of the criminal process.

1. Overview and typology of police discursive practices

In order to present an overview of police discursive productions, this section describes the different types of intended audience and the stakeholders with whom police officers interact while on duty (Subsection 1.1) and then it highlights the main specialized purposes they serve (1.2).

1.1. Interactions with multiple stakeholders

Several authors have underlined the necessity to analyze discourse by taking into account the target audience and purpose (Resche, 2011: 120) as well as the difference between internal discursive flows and discourse directed outwards from the community (Beacco and Moirand, 1995: 50). When they carry out their duties, police officers constantly interact with multiple actors: police peers, scientific experts, legal professionals (lawyers, prosecutors, judges…) and members of the general public. Four main types of intended audience and specialized discursive practices can be identified: internal communications (police ↔ police), productions intended for judicial bodies (police → judicial bodies), interactions with one or more members of the public (police ↔ member(s) of the public), and productions intended for the general public (police → general public). Table 1 presents various examples of discourse produced for each type of intended audience.

Table 1: Typology of police discursive productions

| Type of discourse (intended audience) | Examples of corresponding discursive productions |

| police ↔ police | intranet articles; pocket notebooks (UK); Codes of ethics; radio communications; emails; custody records; letters; manuals, guides, directives…; force journals/magazines; roll calls (US); call logs, arrest logs, event/incident logs, evidence logs, missing person inquiry logs |

| police → judicial bodies | emails; meetings; letters; police reports; court testimonies |

| police ↔ member(s) of the public | emergency calls; interviews/interrogations; diverse exchanges during patrols, traffic stops, demonstrations, searches, seizures, etc.; arrests; cautions (UK) and Miranda warnings/rights (US) |

| police → general public | autobiographies; crime prevention campaigns; press releases and press conferences; booklets, flyers; specialized dictionaries, glossaries and encyclopedias; memoirs; podcasts; annual reports; force official websites and social media; personal websites and social media |

Most of the discursive productions listed above are discourse genres. As defined by Swales (1990: 45‑57), a genre is a class of communicative events, which implies a shared set of communicative purposes. Genres vary in their prototypicality and their production is shaped by constraints in terms of content, positioning and form. Finally, genres provide insights into the specialized discourse community. However, an in-depth study of each type of discourse would be necessary to scientifically validate this status. Moreover, these four categories are permeable, as discursive productions initially intended for a particular audience (or type of interlocutor) can be made accessible to other stakeholders. For instance, British police officers carry on pocket notebooks (PNB) at all times when on duty and an entry is made every day to record evidence relating to an offense or an investigation. Specific rules and discourse conventions need to be followed, regarding the type of information recorded (date, place, presence of other police officers, type of incident, information on the person being interviewed, actions carried out by the police officer…), as well as the diverse contexts in which the police officer may use the PNB, the color of the ink, erasures and the compulsory use of direct speech (Hampshire Constabulary, 2015; West Mercia Police, 2021). Police officers consult these notes when writing police reports at a later stage (police → police), but PNBs also provide support when conducting an interview (police → member of the public) or when testifying in court (police → judicial bodies), either to refresh memory or to quote verbatim evidence of conversation and statement.

1.2. Various specialized purposes

Police discourse practices serve various interrelated specialized purposes and five main categories can be distinguished: (1) communicating in order to guarantee operational efficiency; (2) collecting elements that are useful for the investigation and the judicial process; (3) recording, documenting and reporting on facts and operational activities; (4) supervising and regulating specialized practices; and (5) carrying out prevention operations.

1.2.1. Communicating in order to guarantee operational efficiency

Several discursive genres serve specialized aims by contributing to internal communication within the institution and to the effectiveness of field operations. For instance, radio communications are used daily by police officers on patrol and during interventions to communicate with dispatch and with the control room. Exchanges and turn taking are highly scripted, formatted and standardized (Johnson et al., 1993: 6) as brevity and efficiency are key. Specific procedures codify these spoken exchanges, such as the use of call signs (to quickly identify participants), the NATO phonetic alphabet (Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, etc., to simplify spelling) or “procedure words” (also called “prowords”) like “Copy” or “Roger” (to notify your interlocutor that you understood the message). Another example would be the “ten codes” (“ten one”, “ten two”, “ten three”, etc.) used by officers during radio transmissions in the United States and the “state codes” (“state one”, “state two”, “state three”, etc.) in the United Kingdom. Each code refers to a specific and longer utterance. For example, to indicate that a police officer is in danger, a member of the New York Police Department uses “10-13” in their radio transmission and a British officer uses “state zero”. Moreover, other police discourse productions also serve the shared professional intentionality by ensuring the circulation of information within the institution. Articles published on the intranet, letters, emails and force journals and magazines2 are some examples. These discursive practices contribute to the spreading of specialized instructions and knowledge across the profession.

1.2.2. Collecting elements that are useful for the investigation and the judicial process

One of the central aspects of police work is the gathering of elements that will be useful for the investigation and in the subsequent judicial process. In order to serve this specialized purpose, officers on duty carry on various professional acts: interviews, identity checks, roadside checks, management of police informers, undercover operations, arrets, patrols, searches, seizures, emergency calls… During these exchanges, specialized purposes are of the utmost importance. For example, in the case of emergency telephone calls (999 in the United Kingdom and 911 in the United States), exchanges are controlled and oriented in order to obtain all the essential pieces of information needed to ensure the necessity, specificities and urgency of the required intervention (Garner and Johnson, 2013: 35; College of Policing, 2020b). Besides, in the event of a field intervention, information gathered during the call is invaluable to police officers, contributing to their safety and efficiency in the field (Rock, 2018: 7). Similarly, the police interview – also referred to as “police interrogation” in the United States – is a particularly useful tool for gathering information and evidence that will be useful and exploitable in the subsequent judicial process (Baldwin, 1993: 325; Magid, 2001: 1182; Milne and Bull, 2006: 8). This stage is an essential step in the police sequence (Vlamynck, 2011: 58), and this discursive genre is at the service of police intentionality (Walton, 2003: 1772), as the elements gathered during the interviews can be decisive in the progression – or even solving – of a case. Hence, various linguistic, discursive and rhetorical strategies are used by police officers to collect evidence when conducting victim, witness and suspect interviews (Cartron, 2023a).

1.2.3. Recording, documenting and reporting on facts and operational activities

Police officers are frequently required to report their activities and findings to their superiors, relevant judicial authorities or the general public. This specialization is at work in several discursive productions of British and American police, including press releases, press conferences, interviews with decision-making authorities (to obtain a warrant, for example), pocket notebooks, police reports, annual reports, court testimony and logs. In both countries, police accountability is closely linked to issues of transparency and to the legitimacy of policing activities and powers (Reiner, 2000: 183). The police institution must be able to trace and justify the actions and decisions of its officers, which is why they regularly record, document and account for their activities. For instance, police reports are essential and central discursive genres in the unfolding of the police sequence and judicial handling of a case and they must meet a set of specific criteria in order to serve their specialized purpose. They must be: precise, clear, concise, factual, objective, impartial, free of personal opinions and written in correct English, in terms of spelling, grammar and punctuation (Torregrosa and Sánchez-Reyes, 2018: 116). An American Police Sergeant, interviewed in June 2020, explained that this genre is characterized by discourse conventions, in terms of linguistic features and content, and stated:

When it comes to police officers or Detectives writing reports, sure, it’s a definite style. It’s very mechanical. There isn’t a lot of fluff. It usually starts out on day, date and time. So, “On Thursday, May 4th, at about eleven ten a.m., myself, Sergeant [states his first name and surname], on Squad 21 15 observed…”, then you go into whatever the story is. Or “I was dispatched to a call with a man with a gun. Upon arrival, I observed” or “I spoke with”. […] The writing style and how they write the reports are pretty uniform. It all starts out with “On day, date and time, I was dispatched to”, “I respond to”, “I observed”, blah blah blah. You’re always gonna cover the who, what, when, why.

Police reports feature a number of linguistic and discursive specificities, including the frequent use of adverbial phrases of time and place, passive voice, specialized legal terms, formal register and first and third person singular (Fox, 1993; Johnson et al., 1993; Hall, 2008). Besides, the communicative aim of police reports is to present a series of facts but also to model discourse in order to provide usable content for the judicial process (Cartron, 2023c). A transition is operated “from witness[/suspect]-speak into something that the legal process can use” (Rock, 2001: 67). When it does not comply with these generic conventions, a police report fails to fulfill its function and to serve specialized purposes, jeopardizing the credibility of the facts recorded and, to a certain extent, the entire case.

1.2.4. Supervising and regulating specialized practices

Several discursive practices also serve specialized purposes by helping to regulate and supervise specialized practices. For instance, in the United States, operational police officers take part in a daily meeting called “roll call”. Lasting around twenty minutes before the start of each shift, these briefings serve a dual purpose: informative and operational. The superior in charge of the meeting – usually a police sergeant – forms the different squads, allocates vehicles, assigns the various tasks and cases, distributes mail (summonses, reports returned for correction…) and presents the new regulations that have come into force (O’Donnell, 2019: 164). The degree of formality and the modes of address vary depending on the superior chairing the meeting. Specialization is reflected not only in language, but also in clothing as all officers must wear their uniforms and equipment. Furthermore, the practices of the specialized discourse community are also framed and regulated by manuals, guides and codes of ethics. These documents specify the rules, values and principles that should dictate the police personnel’s actions and govern their behavior in order to best serve specialized goals. Finally, professional practices are also governed by the law, and certain discursive productions have the primary aim of placing the officers’ actions within a legal framework. For instance, when a suspect is taken into police custody to be interviewed, police officers in the UK and the US are required by law to notify them of their rights. This formal notification of rights (“caution” in the UK and “Miranda warning” in the United States) is highly scripted and formulaic, as displayed in numerous movies and TV series: “given the global reach of the American entertainment industry and its cops-and-robbers movies and television dramas, the Miranda warning, beginning with the phrase, ‘You have the right to remain silent’, may be the most well-known criminal law tenet in the world” (Ainsworth, 2012: 287‑288). In practice, any change in the phrasing would invalidate information obtained during the interview and prevent the use of these elements in court.

1.2.5. Carrying out prevention operations

Finally, other types of discourse produced by the police institution are related to prevention operations, as prevention is one of the essential aspects of specialized police intentionality. They include, among others, brochures, leaflets, flyers, official police force websites and social networks, as well as campaigns in educational establishments (in primary schools and high schools, for instance). These initiatives contribute to the creation of a communicative interface with members of the general public and to the sharing of diverse information.

As discussed above, each police discursive production is characterized by its own specific linguistic and rhetorical features; nevertheless, all these types of specialized discourse directly serve professional purposes. They are complementary, as well as closely interrelated and interweaving as cases, investigations and the judicial process unfold.

2. Discourse networks and interrelations between genres in English for Police Purposes

2.1. The police sequence, a network of discourse productions

As Hyland (2013: 107) points out, genres form “constellations” with neighboring genres or “genre sets” when “spoken and written texts cluster together in a given social activity”. Several researchers in the field of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) have investigated these interrelations (Paltridge and Starfield, 2013: 348), using the notions of “systems of genres”, “genre networks”, “genre chains”, “genre sets” and “repertoires of genres” to describe relations between genres (Bazerman, 1994; Tardy, 2003; Devitt, 2004; Swales, 2004). Police discourse is characterized by a series of interconnected communicative events involving multiple actors and multiple means of communication over an extended period of time (Garner and Johnson, 2013: 39). Most of the discourse produced to serve the professional purposes of the police form a network of interrelated discourse productions that can be called the “police sequence”. This linear sequence (Hyland, 2002: 123) is made up of an ordered network of successive discursive elements vectored according to a pattern < beginning → end >, triggered by the commission of an offense and, ideally, ending with the solving of the case and its transfer to the competent judicial authorities. The main stages of the police sequence are: the triggering event (emergency call, complaint, flagrante delicto3, for instance), collection of evidence (physical evidence at the crime scene, victim or witness interviews, searches…), suspect identification and management (notification of rights, police custody, interview…) and then transfer of the case to judicial bodies. Each stage requires specific police acts as well as different types of discursive practices, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Network of related discourse productions throughout the police sequence

For instance, in order to collect evidence (second phase of the police sequence), police officers can carry out various professional acts that comprise the gathering of physical evidence on the scene, searches, seizures, victim and/or witness interviews or interrogations. Several discourse practices are related to this stage, including logs (such as evidence log or missing person inquiry logs), police reports (crime reports, incident reports, investigation reports, traffic accident reports), victim/witness interviews and statements. The use of one genre is related to and influenced by a number of other interrelated genres and they form together systems of genres (Bazerman, 1994) that organize and orchestrate the profession (Hyland, 2002: 124). For example, the spoken exchanges that take place during the witness/victim interview influence the content of the written witness/victim statement elaborated by the police officer afterwards.

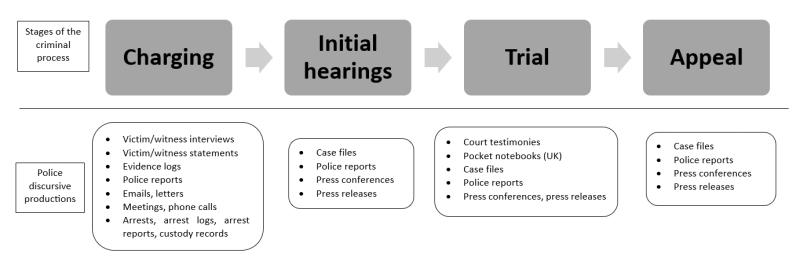

Multiple police genres, produced during investigations to record, document and report facts and operational activities, are ultimately compiled to form the court case files. For example, in February 2024, when Ruby Franke, a former parenting influencer on YouTube, was sentenced to prison for aggravated child abuse, the Washington County Attorney’s Office released court case files.4 They included numerous police productions, such as audio and video recordings (bodycam footage, interview recordings, …), photos as well as written documents (such as witness statements, press releases and detailed incident reports). The police sequence can thus also be integrated in the broader sequence of the legal and judicial process. The police investigation is followed by – or very often intertwined with – the different steps and discourse productions of the criminal process. These different steps are presented in Figure 2 in a very simplified way, as there are multiple variations depending on the country under study or the type of case, for example. The major phases include: charging, initial hearings, trial and appeal. Similarly, each of these steps requires specific discourse productions and genres.

Figure 2: Network of related discourse productions throughout the criminal process

2.2. Potential variations

The police sequence is subject to potential variations. On the one hand, some stages presented in Figure 1 might not be necessary. For instance, a case may be closed without prosecution for a number of reasons, including the use of alternative measures such as a reminder of the law or the payment of a fine, or when there is insufficient evidence. As a result, not all cases handled by the police lead to prosecution or the transfer of the case to judicial bodies (prosecutor, courts…). Besides, more stages could be added to the police sequence, such as the collection of additional evidence after the defendant has been heard or the gathering of intelligence, through surveillance, telephone tapping, undercover work or the management of police informers. Moreover, the order of the different stages of the police sequence and the police actions carried out may vary depending on the information available to the investigators at the outset of the case:

Every investigation is different and may require a different route through the process, e.g., in some cases the identity of the offender is known from the outset and the investigation quickly enters the suspect management phase. In others, the identity of the offender may never be known or is discovered only after further investigation. (College of Policing, 2020b)

Likewise, the nature of the triggering event and the classification of the offense determine the necessary professional acts and corresponding discourse practices. The categorization occurs very early in the police sequence, for example, as soon as the emergency call is received, as evidenced by call logs classifying reported events in specific categories of criminal offenses. It can evolve during the course of the investigation, as new evidence is discovered, and it determines the department to which the case is assigned, the type of evidence that needs to be collected, the acts carried out by the police and the corresponding spoken and written discourse practices. Besides, the cultural specificities of the legal context also need to be taken into account, as they impact the different steps of the police sequence.

From one step of the police sequence to another, discourse practices are interrelated and each genre is part of a constellation with neighboring genres, clustering together to serve specialized purposes. Discourse productions are interweaving and complementary as the investigation is carried out and the case is prepared for the subsequent judicial process. At the different steps of the criminal process, evidence collected and information gathered transition from original raw material to elements that can be used in court, thus implying discourse modelling and textual travels.

3. Discourse modeling and textual travels in English for Police Purposes

The role of the police officer is to collect, sort and select information throughout the investigative process in order to “‘set the scene’ for the court and jury” (College of Policing, 2020a). As a result, during the police sequence, each stage models the narrative of the facts according to both the specialized professional intentionality it serves and the requirements of the next phase. In order to illustrate this process of discourse modelling, three examples are explored below: emergency calls to the police (3.1), suspect/victim/witness interviews (3.2) and police reports (3.3).

3.1. Emergency calls to the police

When an emergency call is received by the police, so from the very beginning of the police sequence, the account of the incident initially given by a member of the public is modelled so that it can be used in the rest of the policing sequence:

The call from a member of the public is not an isolated, fixed communicative entity; it is rather the initial construction of a dynamic and fluid text as it enters the police domain, and it is reconstructed and re-entextualized as it passes through a range of organizational, operational contexts and technological mediation. (Garner and Johnson, 2013: 37)

For instance, in February 2025, the Santa Fe County Sheriff’s Office released audio from the 911 call related to the discovery of the bodies of actor Gene Hackman and his wife at their home in Santa Fe (New Mexico).5 In the following extract, the 911 operator is methodically collecting information that will then be transmitted to dispatch and to officers on duty:

911 operator (hereafter O): Santa Fe 911, what is your emergency?

Caller (hereafter C): Hello, my name is [name6]. I’m the caretaker for Santa Fe Summit […]. I think we just found two or one deceased person inside the house. […]

O: OK. What’s gonna be the address?

C: [address]

O: How old is the patient?

C: I have no idea.

O: You don’t know? OK, that’s fine. Is the patient a male or a female?

C: A female and a male probably. […]

O: Are they awake?

C: I have no idea.

O: Are they breathing?

C: I have no idea. I’m not inside the house. It’s locked. I can’t go in. But I see them. I see them laying down on the floor from the window. […]

O: OK. My units are on their way. […] Is there any way you can open the house?

Raw information obtained during a call is then filtered through the prism of specialisedness during various communication events involving multiple actors. Garner and Johnson (2013: 37‑51) describe this process as “textual travels” and identify six communicative events. At each of the six stages, illustrated by Figure 3, a reformulation and a modelling of discourse content are carried out: (1) initial text (i.e. communication between a member of the public and the call handler); (2) text entered in the computer by the call handler (for dispatch) and summarizing the information; (3) communication between dispatch and the officer; (4) exchanges between the officer and stakeholders on the scene; (5) brief report made to dispatch; and (6) report on the event written later by the officer.

Figure 3: Communicative events and textual travels related to emergency calls to the police

Additional texts are also related, such as officers’ pocket notebooks or logs for example. These interconnected communicative events are characterized by a process of discourse modelling that occurs at each stage: information collected during the initial exchange is filtered and reformulated in order to guarantee operational efficiency. Textual, and especially lexical, transformations that occur between the initial emergency call and the police report can sometimes be traced back, as in the following extract from a report written in 2018 by an officer of Rogers County Sheriff’s Office:

On 08/01/2018 at approximately 0844 hours, Deputies were assigned to investigate a report of a man having sex with a pony at the intersection of [address]. [Person 1] was leaving for work and observed a white male full nude standing in the field having sex with a pony. [Person 1] called her neighbor [Person 2] and asked her to go check it out and call the police. When [Person 2] and her daughter [Person 3] arrived, they also witnessed a white male standing behind the pony full nude, and what looked like he was having sex with the animal. [Person 2] said when her daughter started to video, he stopped what he was doing and started walking towards them. Video evidence is attached to the report, the suspect was identified as [Person 4] DOB [date of birth], he was arrested for Indecent Exposure and Bestiality.

This extract warrants attention for two main reasons. Firstly, in this final report (Step 6), several prior communicative events can be identified. The initial call to the police (Step 1), is mentioned: “[Person 1] […] asked her to go check it out and call the police”. This triggering event then led to a radio communication between dispatch and officers (Step 3): “Deputies were assigned to investigate a report of a man having sex with a pony at the intersection of [address]”. When they arrived on scene, officers conducted witness interviews (Step 4) and information provided by the witnesses during these interviews are referred to using mostly the preterit tense (“observed”, “called”, “asked”, “arrived”, “witnessed”) as well as reported speech (“[Person 2] said”). Thus, this extract illustrates the interconnection of communicative events throughout the different steps of the police sequence. Secondly, it exemplifies the travelling of a single piece of information from one communicative event to another, being modelled to best serve professional purposes. One striking example is the lexical transition from “man having sex with a pony” to “Indecent Exposure and Bestiality”. The former is the first reference to the offense in the report and it mirrors the wording used by the lay witness when they called the police and then transmitted as such by dispatch; whereas the latter is the formal and specialized term used in legal texts to refer to this type of offense. A transition was operated from a non-specialized phrasing to specific legal terminology, in order to insert the facts into the wider context of the legal system.

3.2. Suspect/witness/victim interviews

Throughout the police sequence, officers gather information and drive the case in the direction of one or more common law precedents: “legislators codify offences ex ante,7 and […] police and prosecutors confine their collective attention to the catalogue of what has already been defined as criminal” (Bowers, 2014: 997). Hence, the legal framework determines the exchanges as well as the selection of information. For instance, while investigating Ruby Franke’s aggravated child abuse case mentioned earlier (Section 2.1), the police interviewed her ex-husband, Kevin Franke.8 The aim of this interview was to determine if he was aware of the neglect and abuse inflicted upon his children, as explicitely stated by the detective: “My job is to find out about your knowledge of the treatment of these […] children”. According to Utah’s state legislature (specifically, Utah Code Section 76-5-109):

An actor commits child abuse if the actor:

(a) inflicts upon a child physical injury; or

(b) having the care or custody of such child, causes or permits another to inflict physical injury upon a child. (le.utah.gov.)

This legal framework guided the exchanges as several questions were asked to Kevin Franke to determine if he knew about such practices: “When was the last time you physically saw [your children]?”, “Did you ever try to reach out to the kids?”, “Are you aware of how [your wife] handles the kids’ behavioral issues?”, and “Are you aware of the physical condition of your children?”.

Moreover, the exchanges that take place during interviews of suspects, witnesses and victims are then subject to textual travels and are mentioned in numerous discourse productions and genres. As illustrated by Figure 4, the content of these interviews are quoted in suspect/witness/victim statements but also in other documents throughout the investigation and criminal process, including various police reports, case files, pocket notebooks, meetings with legal professionals, press conferences and releases. Such elements are also quoted, sometimes verbatim, as evidence in court during trials.

Figure 4: Police interviews and related discourse productions

In the case files released by the Washington County Attorney’s Office, Kevin Franke’s interview is mentioned several times, illustrating this process of textual travels. For instance, in the detail incident report (DIR), a one-page description summarizes the 30-minute interview, focusing exclusively on elements that will be useful in the upcoming steps of the judicial procedure. The officer then concludes “I believe that Mr Franke did not have involvment in the abuse and neglect of Child 2 and Child 1” (DIR, 09/13/2023, 19).

Finally, the legal framework determines how information is selected but also how it is transformed. In order to be consistent with the description of the offense in the legislation, textual elements are reformulated, to the point that the initial dialogue or words used by the victim, witness or suspect during the interview are modified. For instance, in her discourse analysis of police interviews with suspected pedophiles, Benneworth (2009: 561-562) quotes a police officer conducting a suspect interview as follows: “she says you were masturbating yourself […] you would be watching pornographic videos […] and she says you’d make no attempt to try and hide it and your erect penis was clearly visible” (our italics). The police officer uses reported speech (with the utterance “she says…”), supposedly quoting the words of the victim previously interviewed. However, it is highly probable that the terms in italics were not used verbatim by the 12-year-old-girl and that these specific terms were included to fit the vocabulary used in legal descriptions of the offense. Such a process of discourse modelling also occurs – and is even more visible – when officers write police reports intended for judicial bodies and legal professionals.

3.3. Police reports

The legal framework heavily influences discourse conventions, especially in terms of report writing. A police report (or record of suspect interview) exclusively focuses on elements that will be useful and exploitable in the next steps of the judicial process and the interviewee’s words are modelled to meet this professional goal. The following sentences are extracted from a short descriptive note (SDN) written by a Detective Constable of the Kent Police in 2004 (our italics):

The defendant admitted entering the shop with the intention of stealing food.

The defendant knew it was wrong to steal and agreed that her actions were dishonest.

The defendant stated she had every intention of eating the food items she stole.

Firstly, it is rather obvious that these statements do not quote the suspect word by word but are rather the result of a dialogue. We can read between the lines that the suspect answered affirmatively to questions such as “Did you have the intention of stealing and eating the food?” or “Do you know that this behavior is against the law?”. The words of the suspect and those of the police officer are strongly intertwined and information initially suggested by the police officer sometimes becomes an integral part of the suspect’s speech. Besides, the suspect’s statement is modelled in order to fit into the legal framework and to tally with the description of the offense of “theft” in British legislation. The SDN can be compared with the following extract from the UK 1968 Theft Act:

(1) A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it; and “thief” and “steal” shall be construed accordingly. (legislation.gov.uk, our italics)

Striking similarities can be identified between the SDN and the legal text and were underlined in italics. The sentence “The defendant admitted entering the shop with the intention of stealing food” (SDN) establishes – without doubt – that the defendant intended to commit an offense. In criminal law, the intent to commit a crime is a foundational element, as it differentiates intentional criminal behavior and innocent mistakes or accidents. A parallel can be drawn between “she had every intention of eating the food” (SDN) and “with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it” (Theft Act). In addition, the SDN also explicitly refers to the criminal offense category of “theft”, when the law specifies that “‘thief’ and ‘steal’ shall be construed accordingly”. Finally, “the defendant […] agreed that her actions were dishonest” (SND) undeniably echoes “dishonestly” (Theft Act). These findings echo Coulthard and Johnson (2007: 59)’s analysis of an interview with a woman suspected of stealing money. They shed light on the hybridity and intertextuality of police discourse, emphasizing the lexical similarities between the Theft Act defining the offense and the closing stages of the interview:

A comparison of the two reveals the inbuilt generic hybridity present in many of the legal genres. On the surface, the talk […] appears to be summing up and closing the questioning phase of the interview, but it subtly incorporates the legislative genre […] within it […]. The effect is to produce a complex and powerful set of communicative actions that create interpretative challenges for the lay participant in the talk and also for observers and analysts.

As a result, police discourse and genres are not communicative events that occur in isolation but rather need to be considered as intrinsic parts of a wider process (Haworth, 2006: 741).

Conclusion

To conclude, English for Police Purposes is an interesting, multifaceted and complex object of study. Investigating this specialized variety of English through a discourse perspective allows for shedding light on the linguistic, generic and rhetorical characteristics of police English and to show that it is composed of multiple discursive productions that are closely linked with other communicative events and genres, distributed throughout the police sequence. There is a constellation or network of discourses and genres that are related together to serve the purposes of the specialized domain, i.e. to gather and then present elements that will be exploitable in the subsequent judicial process. In order to understand specialized practices and discourse conventions, it is thus necessary to place English for Police Purposes in the broader context of the judicial and criminal process. This multidimensional approach relates texts and discourse genres (intratextual perspective) to professional and cultural practices (extratextual and contextual dimensions) of specialized environments. Such a holistic approach offers ESP researchers the possibility to thoroughly investigate their objects of study and to shed light on the diversity, complexity and interrelations at work within specialized languages.