A special thanks to Jérémy Michot, Chloé Huvet, and Grégoire Tosser for their organizational and editorial work that led to the creation and publication of this article. I also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers that contributed significantly to the improvement of this work.

During the 1970s trend of synthesized film scores, John Williams’s late-romantic symphonic style in the Star Wars films is often credited as the beginning of a renaissance of classical film scoring. Scholars such as Emilio Audissino (2014), Kathryn Kalinak (1992), Michel Chion (1995), Frank Lehman (2018), and Chloé Huvet (2022) among others, recognize Williams’s scores as being marked by this distinctive neo-romantic orchestration style coupled with memorable melodies, many of which are used as leitmotifs throughout his works. As Lucasfilm Ltd. and The Walt Disney Company continue expanding the Star Wars franchise through the creation of live-action television series, the scoring of this expanding universe is passing from Williams to several composers including Natalie Holt, Nicholas Britell, Kevin Kiner, Michael Abels, Ludwig Göransson, and Joseph Shirley. This article explores the continuation of Williams’s legacy in the scores for the Disney+ Star Wars television series The Mandalorian (2019, produced by Jon Favreau, scored by Göransson) and The Book of Boba Fett (2021, produced by Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, and Robert Rodriguez, scored by Göransson and Shirley).

The following soundtrack analysis builds on the existing body of work on leitmotivic analysis in film music including the work of James Buhler (2000), Justin London (2000), Matthew Bribitzer-Stull (2015), Frank Lehman (2018), and Chloé Huvet (2022). In his monograph Understanding the Leitmotif (2015), Bribitzer-Stull follows the development of the leitmotif from its origins in the musical dramas of Richard Wagner to its modern-day use in popular visual media. After considering existing definitions of leitmotif—the simplest of which is that the leitmotif is a short, recurring musical idea imbued with semantic meaning (Darcy 1993, 45)—Bribitzer-Stull introduces the following three characteristics of leitmotifs.

1. Leitmotifs are bifurcated in nature, comprising both a musical physiognomy and emotional association.

2. Leitmotifs are developmental in nature, evolving to reflect and create new musico-dramatic contexts.

3. Leitmotifs contribute to and function within a larger musical structure (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 10).

Following Bribitzer-Stull and his evolution metaphor, this analysis of the development of leitmotifs for the character Boba Fett includes elements of “mutation” within a theme and “evolution” between themes. Lehman has built on Bribitzer-Stull’s work in his own text Hollywood Harmony (2018) and in his catalog of leitmotifs in Star Wars films (2023). The following examination of leitmotifs in The Book of Boba Fett builds on Lehman’s work as the series includes quotations, mutations, and evolutions of Williams’s original character leitmotifs1.

This article adds not only to the body of scholarship on leitmotivic analysis, but also to the existing work—including other articles included in this journal issue—on Williams’s compositions for the nine films of the Star Wars Skywalker saga2. In this article, I consider 1) evidence of Williams’s legacy in the Star Wars television scores of Göransson and Shirley in the direct quotation and evolution of Williams’s leitmotifs, 2) Göransson and Shirley’s creative mutation of leitmotifs to parallel character development and 3) Göransson and Shirley’s use of multiple leitmotifs for a single character to highlight the non-linear narrative structure of the show.

The Book of Boba Fett is an optimal case study for the continuation of Williams’s legacy in the adaptation of Star Wars for television since it prominently features characters and leitmotifs from the original movie trilogy while also introducing and developing new leitmotifs. While the score for The Book of Boba Fett is the primary focus of this article, elements of the score for The Mandalorian will also be considered briefly due to the recurring appearances of characters and leitmotifs across both series and Göransson’s work on both shows. It is worth noting here that due to the use of the word “Episode” in the titles of the nine films in the Star Wars Skywalker saga, and to remain consistent with the terminology used by Disney+ in The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett, I will use “Chapter” to refer to episodes in both television series.

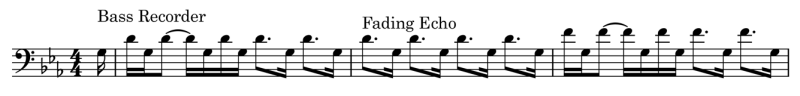

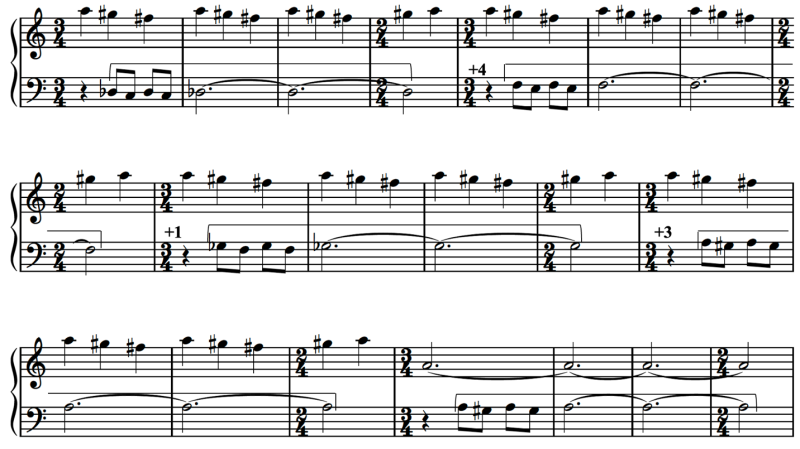

In The Mandalorian, Göransson introduced viewers to a new Star Wars sound that exchanges Williams’s sweeping melodies for more minimalistic character themes that rely heavily on timbral association. Take, for example, the first music heard in the pilot episode of The Mandalorian—the unaccompanied leitmotif associated with title character Din Djarin. This melody, as shown in Figure 1, contains only three distinct pitches played on bass recorder—an unfamiliar timbre to many. While the old and new Star Wars music styles may be initially perceived as contrasting, Göransson’s openness about the scoring process in interviews provides evidence for his deliberate emulation of Williams in certain elements of The Mandalorian score. In an interview with Variety (2020), Göransson specifically mentions the fanfare at the climax of The Mandalorian title track, recording with a 70-piece orchestra, and the use of 1970s Mellotron and Rhodes synthesizers all as ways of honoring Williams and the music of the original Star Wars trilogy.

Figure 1

The Mandalorian, Din Djarin’s leitmotif.

In addition to the elements Göransson specifically mentions as a deliberate nod to the symphonic style of Williams, Göransson and Shirley also pay homage to Williams through the quotation and evolution of Williams’s original leitmotifs. After a brief overview of the plot of The Book of Boba Fett, this article will consider Göransson and Shirley’s quotation and repurposing of Williams’s motifs and their presentation and development of new leitmotifs to highlight character growth in each of two main timelines.

Leitmotivic Quotation and Transformation in The Book of Boba Fett

The Book of Boba Fett is a 7-chapter Star Wars miniseries that debuted on Disney+ in 2021. The series follows Star Wars’ original Mandalorian armor wearing bounty hunter. Boba Fett is introduced as a live-action minor character in the original trilogy of Skywalker saga films in Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back. Fett is a masked Mandalorian bounty hunter working for the empire and Darth Vader. This iconic character favors actions over words as evidenced in his speaking of only four lines of dialogue and appearing on screen for a mere six-and-a-half minutes across two full-length feature films (Episode V and Episode VI) (Baruh and Kwan 2021). In Episode VI – Return of the Jedi, Fett falls into the jaws of the monstrous Sarlacc pit where he presumably died a slow and painful death. Boba Fett miraculously returned for a few chapters of Season 2 of The Mandalorian to set up the impending release of Fett’s own television series.

The Book of Boba Fett follows a non-linear narrative that consistently follows the title character in two timelines—each of which has a distinct musical profile as considered in the second main section of this article. The first timeline tracks Fett’s present rise to power as the new crime lord of Mos Espa, Tatooine, while the second consists of flashbacks to explain Fett’s miraculous escape from the Sarlacc pit and his personal development first as a slave and then a member of a Tuscan Raider tribe. The original soundtrack for the show credits Ludwig Göransson for writing the themes and Joseph Shirley for composing and orchestrating the remainder of the score. The following section considers Shirley’s employment of Williams’s original character themes in the latter-episodes of the series.

Direct Quotation of Williams’s Leitmotifs

In Chapters 5–7 of The Book of Boba Fett, The Mandalorian characters Din Djarin and his foundling child Grogu—a force-sensitive youngling resembling Yoda—are given a significant amount of screen time including interactions with original trilogy characters Luke Skywalker and R2-D2. During these scenes, Shirley references Williams’s scores through the quotation of the “Yoda” and “Force” leitmotifs3. Shirley’s quotation of Yoda’s motif occurs in Chapter 6 at 12:07 when Luke Skywalker—the main character of the original Star Wars trilogy scored by Williams—is walking with Grogu, reminiscing about Master Yoda. A few minutes later (at timestamp 21:17), Shirley states the force motif during the training montage as Luke is telling Grogu about the ways of the force. The force motif (see Lehman 2023, 6) is present in all nine films of the Skywalker saga and is introduced by Williams in Episode IV – A New Hope4. These leitmotivic quotations coupled with the visual appearances of original trilogy characters—albeit in CGI form—are used not only to acknowledge Williams’s work on the original trilogy, but also in an attempt to strengthen viewers’ emotional connection to the show by visually and aurally appealing to the nostalgia associated with the characters and music of the original trilogy.

Boba Fett Leitmotifs

Rounding out this section on quotation and transformation is an examination of the leitmotifs that have been associated with the character Boba Fett in his various visual media incarnations, beginning with Williams’s original Boba Fett character theme, seen in Figure 2. According to the design team who worked on the original Fett character for The Empire Strikes Back, Fett is intended to emulate an old west gun slinger, complete with jingling spurs in the sound design as he walks—even though no spurs are visually present (Baruh and Kwan 2021). Perhaps it is because of this nuanced sound design detail or because of his position as a minor character that Fett’s theme is only heard only three times, is present only in The Empire Strikes Back (Lehman 2023), and does not initially seem to be present in The Book of Boba Fett series.

Figure 2

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, John Williams’s Boba Fett Theme (modeled after Lehman 2023, 13).

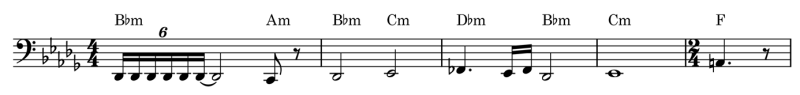

Young Boba Fett appears in the prequel trilogy films; however, his full theme is not present in these films, and he does not receive a new theme from Williams. Due to the Williams’s limited use of the original theme coupled with its absence in prequel trilogy scenes involving Fett as a child, viewers are not likely to remember this theme or associate it leitmotivically with Fett’s character. Besides the Star Wars music scholar community and perhaps a few fans, after so little exposure to this music in the Skywalker saga, it is unlikely that the general viewer would be able to recall Fett’s theme or feel the nostalgic association so commonly held with other Star Wars melodies. The underuse of this leitmotif left room for composers to generate new motifs for the character. Kevin Kiner was the first to generate a new motif for young Boba Fett in the animated series The Clone Wars, produced by Lucasfilm and Dave Filoni (2008–2020), as shown in Figure 3. However, the D-Dorian melody bears little resemblance to Williams’s original theme for the character. Perhaps the emphasis on the raised sixth scale degree rather than the dissonant lowered fifth scale degree of Williams’s Fett motif reflects Fett’s youthful innocence before fully committing himself to a life of crime as a bounty hunter working for the empire. Or, since Fett’s face is shown often in The Clone Wars, this melody could be heard as a “revealed” leitmotif associated not with the masked man of mystery introduced in The Empire Strikes Back, but with the person behind the mask5.

Figure 3

The Clone Wars, Young Boba Fett Theme.

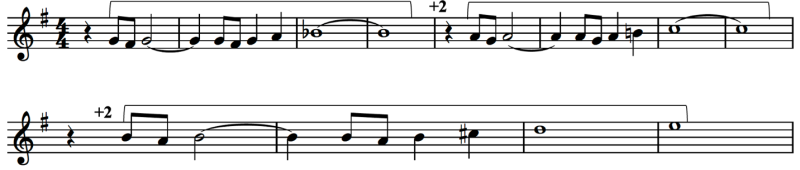

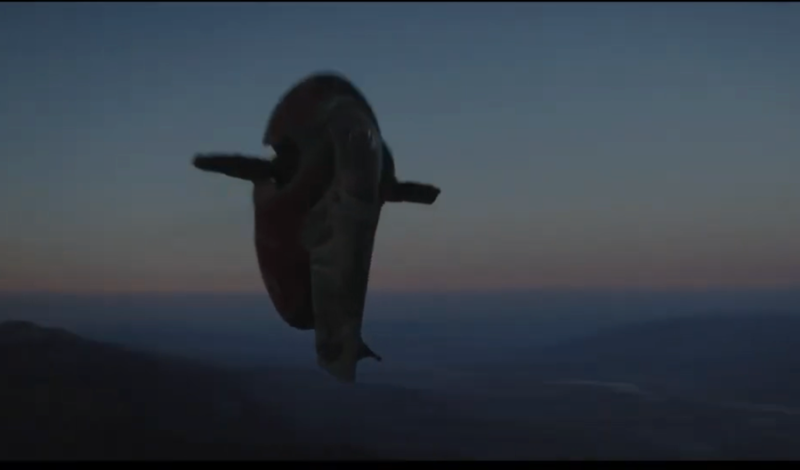

Göransson introduced another new theme for Boba Fett’s reintroduction into the Star Wars universe in The Mandalorian. This theme first occurs in Season 2, Chapter 14 and can be seen in Figure 4b. The theme is heard numerous times throughout The Mandalorian Season 2 and The Book of Boba Fett and is characterized by the dotted rhythms on beats 2 and 4, the downward arpeggiation of a diminished triad that implies a Locrian mode, and the two minor second upper-neighbor figures that close out the theme. The theme occurs in its entirety in the post-credits scene that follows the final chapter of The Mandalorian Season 2. In this scene, Fett and his right-hand, Fennec Shand assassinate Mos Espa ruler Bib Fortuna and claim the throne, establishing Fett’s reign as the new crime lord of the city. This theme recurs 30 times throughout The Book of Boba Fett as a leitmotif that—as we will see in the second section of this article—is directly tied to Fett’s character development in the present timeline. However, it is not used as the main title cue for the show.

Figure 4a

The Mandalorian, Season 2, end credits scene, Shand and Fett on the Mos Espa Throne.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Figure 4b

The Mandalorian, Göransson’s Boba Fett Theme as it appears in the Season 2 end credits throne scene.

Form in “The Book of Boba Fett”

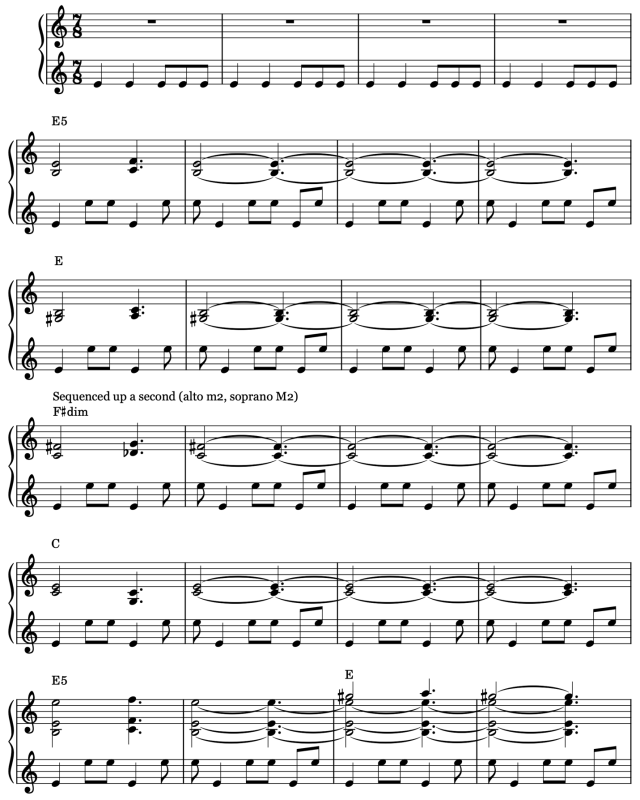

Surprisingly, none of the existing themes are used as the title cue for The Book of Boba Fett. Instead, Göransson composed an entirely new cue that melds together numerous short themes that are unique in their melodic contour, and often their timbre, yet part of a unified whole that serves as the music for a single title character. Following a long history of television themes emulating popular music forms, this cue follows a modified verse-chorus form6. The G-minor title cue has six unique sections, five of which serve as recurring themes associated with Fett’s character throughout the series and two of which are used as leitmotifs specifically associated with Fett’s character development in the past timeline. While the theme can be analyzed using pop-music form terminology, the individual sections are often presented separate from each other and are no longer serving as a “verse” or “chorus” functionally. For this reason, I have elected to identify the individual themes by labels that identify the meter of the theme and an upper-case letter to differentiate between themes of the same meter. A formal summary of the cue can be found in Table 1, and the full title cue “The Book of Boba Fett” can be heard in Clip 1.

Table 1

|

Section |

Thematic Title |

Starting Timestamp |

|

Intro |

11A |

00:00 |

|

Verse |

3A |

00:21 |

|

Intro |

11A |

00:31 |

|

Verse |

3A |

00:41 |

|

Pre-Chorus A |

3B |

00:56 |

|

Pre-Chorus B |

3C |

01:10 |

|

Chorus |

3D |

01:15 |

|

Bridge |

11B |

01:49 |

|

Outro (Intro) |

11A |

02:28 |

Form in “The Book of Boba Fett,” The Book of Boba Fett: Vol 1 (Soundcue Album), Göransson.

The use of a multi-part character theme and its division into more than one leitmotif is not uncommon in the Star Wars universe. In an interview with Craig Byrd, Williams states that “the Luke Skywalker music has several themes within it” (Byrd 2011). Frank Lehman has also observed this pattern and catalogs the “Main Title” (what Williams considers “Luke’s music”) into distinct parts—A and B. Each of these two parts are often presented individually, disconnected from the other half of the theme. After being heard in the Main Title, Main Title A is first presented when the character Luke Skywalker is introduced 17:16 into Episode IV – A New Hope. Main Title B is perhaps most often associated with the iconic throne room scene 01:59:40 into A New Hope7. Because they wrote multiple character themes, Görranson and Shirley are able to add musical depth to Boba Fett’s character by using different themes as leitmotifs specifically associated not only with different timelines and geographic locations, but also with the distinct influences and events that shape the main character’s identity. While it is not uncommon for television shows to present one or more main characters across multiple timelines or geographic locations, Shirley’s deployment of two sets of leitmotifs—one in each timeline—is an innovative and uncommon approach to scoring a non-linear television show8.

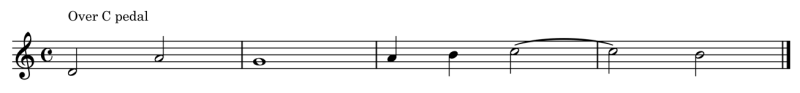

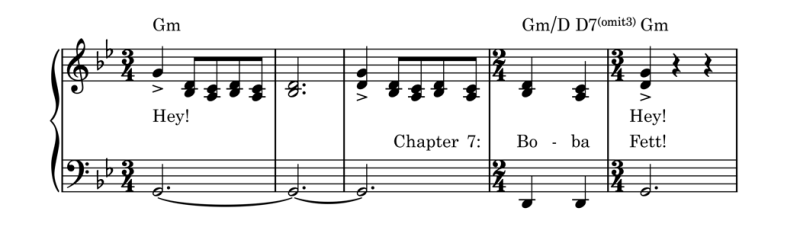

The first theme in “The Book of Boba Fett,” shown in Figure 5, is introduced on strings and alternates between the 5̂ – 5̂ – 1̂ bass line, with a “hey” shout on the downbeat tonic arrivals, and a melody constructed primarily of alternations between scale degrees 5̂ and 4̂. I refer to this theme as “11A” since it is the first theme to appear over a recurring 3+3+3+2 11-beat metric pattern9. Given the two-part nature of this theme, the bass line is often quoted without the accompanying melody and is adapted in the final chapter of the series to include the lyrics “Bo-ba Fett.”10 This theme is used as a leitmotif 12 times over the course of the series—occurring only in the past timeline of the non-linear narrative—and has become so strongly associated with the character that it has also been featured as Fett’s leitmotif in the Disney+ Lego Star Wars Short “Summer Vacation,” produced by David Shayne, James Waugh, Josh Rimes, Jacqui Lopez, Jill Wilfert, Jason Cosler, Keith Malone, and Jennifer Twiner McCarron and scored by Michael Kramer in 2022.

Figure 5

The Book of Boba Fett, Theme 11A.

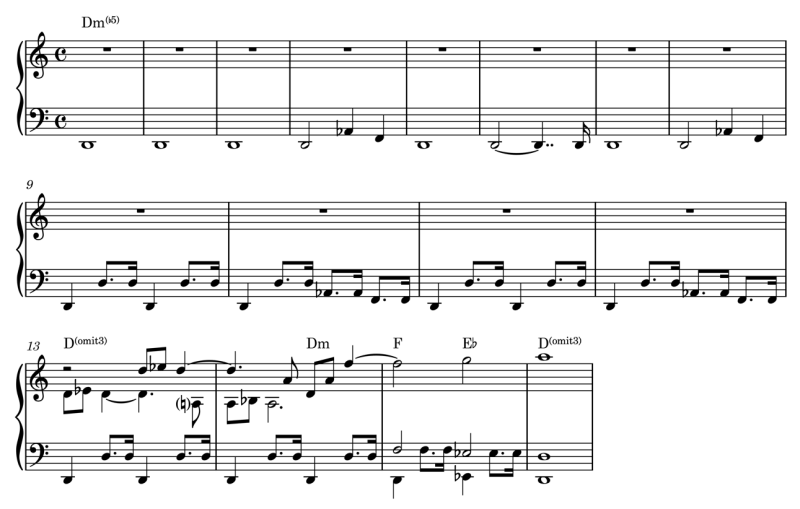

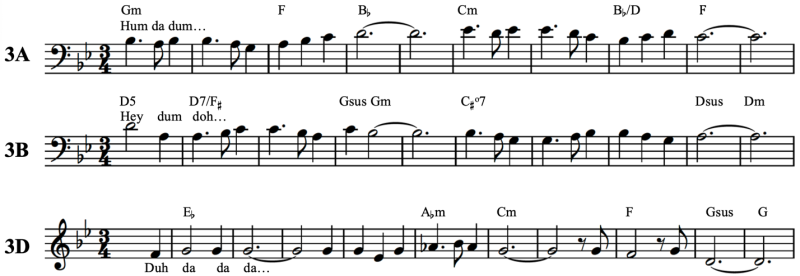

The next four Boba Fett themes in the title cue all feature male chorus and occur in a consistent 3/4 meter. Because of this metric orientation, I will refer to these themes as “the 3 themes,” shown in Table 1 and Figure 6 as 3A, 3B, 3C, and the climax of the track, 3D. Theme 3A, the verse of the track, begins with a dotted lower-neighbor figure and then traces a stepwise minor pentachord pattern from tonic to dominant. The second half of the theme parallels the first by also beginning with the dotted lower-neighbor motif transposed diatonically up a perfect fourth. Theme 3B descends a perfect fourth from the dominant before bringing back the dotted rhythm and applying it to ascending and descending stepwise patterns filling in the thirds from supertonic to subdominant and from mediant to tonic. Theme 3C serves as a short pre-chorus section that only occurs once in the entire series. Since it is not repeated or developed throughout the series, its transcription is not included in Figure 6. Following 3C, 3D serves as the climax or chorus of the cue and marks a harmonic shift in the piece through mode mixture to end on a GM harmony instead of Gm. In addition to the unique rhythm and pitch profile of each of these 3 themes, each is also differentiated by the vocables paired with it.

Figure 6

The Book of Boba Fett, themes in 3/4 from “The Book of Boba Fett”.

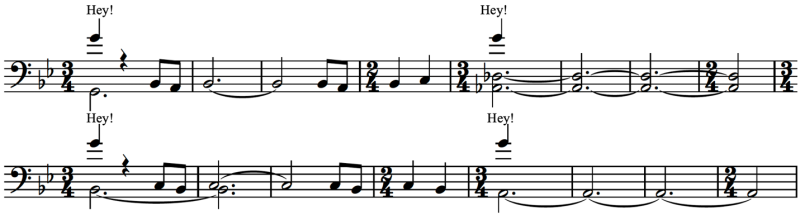

Following the climactic chorus of the cue, a bridge section introduces new melodic material that returns to the 3+3+3+2 metric structure (see Figure 7). After the fuller orchestration and forte dynamic of the chorus (3D), the 11B theme draws back to a much quieter dynamic level and is stripped back to just the melodic neighbor motive and shouts of “hey” over a bass line that is often in unison with the melody. Even though this theme, which I refer to as 11B, occurs only once in the title track, it is the part of the cue that recurs most often as one of Fett’s leitmotifs. Comparing the Tables 1 and 2, one can observe that the 3/4 material comprises the majority of the title cue; however, the 11 material accounts for the majority of the thematic quotation and development over the course of the series. Since the 3/4 themes do not recur often enough to be imbued with emotional significance and do not undergo significant thematic development, I do not consider them leitmotifs. It is the 11 themes that are more strongly associated with the title character through their use as a leitmotif associated specifically with the character’s past timeline. The following section will explore the structure of leitmotif 11B—which recurs 20 times through the show—in greater detail and compare it to Williams’s Fett theme as a prototype.

Figure 7

“The Book of Boba Fett”, Theme 11B.

Table 2

|

Theme |

Number of Occurrences in |

|

Boba Fett from The Mandalorian |

30 |

|

11A |

12 |

|

11B |

20 |

|

3A |

4 |

|

3B |

2 |

|

3C |

1 |

|

3D |

2 |

Theme Quotations in The Book of Boba Fett.

Evolution of Theme 11B

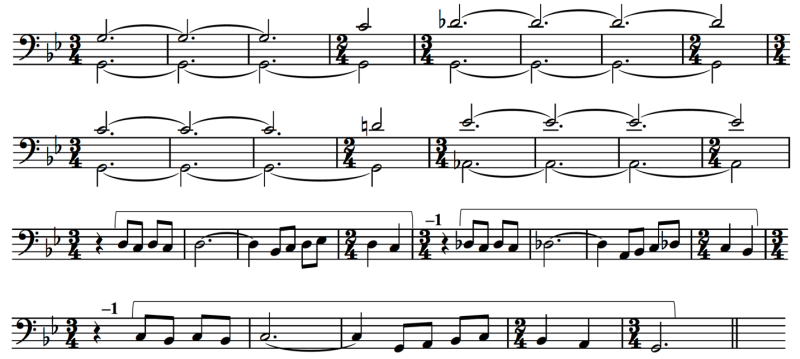

Returning to the idea of thematic quotation and evolution as a means of honoring Williams, this section considers the 11B leitmotif as an evolution of Williams’s Fett leitmotif. Figure 8a shows Williams’s theme divided into three shorter melodic motives. The first, labeled as x in Figure 8, is the descending semi-tone lower-neighbor figure D♭–C–D♭ heard at the opening, 3̂ – 2̂ – 3̂ in the key of B♭m. The second motive, y, elides with x by starting on the concluding D♭ and filling in the minor third up to F♭. A second iteration of x is then presented transposed up a minor third to start on the F♭ that ended y. With the return of D♭, one might assume the pattern would continue with a second ascending stepwise pattern to fill in a minor third. However, the pattern breaks off at E♭ when it is interrupted by an ascending augmented fourth from E♭–A, 4̂ – 7̂ in the B♭ harmonic minor scale.

In the 11B leitmotif, the contour and pitch motivic content from Williams’s original Fett leitmotif feature prominently. Ordered pitch intervals (OPIs) reveal this underlying similarity. The OPIs labeled on Figure 8 indicate the number of half steps between each melodic pitch with + or − to indicate the direction of motion—ascending or descending, respectively. The OPIs indicated in bold are identical between themes. Additionally, both themes begin on 3̂ in a minor key, revealing a similarity not only in OPIs, but also the harmonic context in which they are situated. To start the theme, Göransson replaces the repeated note with the repetition of the entire lower-neighbor figure. While the second half of the Göransson’s 11B motif deviates from the Williams in OPIs, the similarity between motifs continues if we take a pitch-motivic approach. The lower-neighbor idea (x) that occurs twice in Williams’s motif also occurs twice in Göransson’s 11B motif. The ascending minor third (y) almost repeats in the Williams but is interrupted by the tritone (z!). In contrast, Göransson presents the uninterrupted y motive twice, but the second occurrence is notably a transposition of the retrograde variant of y. Finally, the culminating tritone of Williams’s motif is presented not melodically, but harmonically by Göransson at the half-way point of the motif. The climactic D♭ is the highest pitch in the melody and is also a tritone below the downbeat tonic shout of “Hey” that initiates each eleven-beat pattern.

Figure 8

a. Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, analysis of Williams’s Boba Fett Theme.

b. “The Book of Boba Fett,” analysis of Göransson’s 11B Boba Fett Theme.

While the rhythms, harmonies, and timbre differ significantly between Williams and Göransson’s themes, one can consider both melodies as evolving from the same unheard prototype: the alternation between two lower-neighbor figures (x) and two stepwise patterns filling a minor third (y) with a punctuating tritone (z). The transformational relationship between these two leitmotifs reflects Williams’s own developmental practice of which he states, “a theme that appeared in film two that wasn’t in film one [Episodes IV and V] was probably a very close intervallic, which is say note-by-note, relative to a theme that we’d had” (Byrd 2011). Additionally, it aligns with Bribitzer-Stull’s suggestion of evolution—a new theme growing from an existing leitmotif. Continuing the evolution analogy, these three elements—x, y, and z—serve as the “genetic material” for both themes. Both composers adhere strictly to the prototype on the first iteration of the lower-neighbor and passing-tone motives and then allow for development of these two motives when they occur a second time—Williams’s interruption of y and Göransson’s major second x and retrograde of y. In both leitmotifs, the low register and dissonant intervals such as the minor second and the tritone highlight the dark, mysterious bounty hunter’s associations with the empire and the crime syndicates of Mos Espa. Additionally, the construction of the motifs as collections of shorter melodic ideas allows the composers to use not only the full leitmotif, but also shorter derived motifs (see Lehman 2023, 13).

Leitmotivic Mutation in The Book of Boba Fett

As demonstrated in the previous section, Göransson composed multiple themes for Boba Fett’s character and divided the show’s title cue “The Book of Boba Fett” into six short themes, two of which recur as leitmotifs for Boba Fett’s character throughout the show (see Tabs. 1–2 and Figs. 5–8). As noted earlier, the themes in 3/4 are used rather sparingly throughout the show and are not presented or developed enough to be established as leitmotifs. Table 3 shows the nine total occurrences of the 3 themes, four of which—shown in bold—occur in the cue “A Town at Peace” which accompanies the final scene of the series. In this track, the majority of the title cue is played on recorder as Fett walks the streets of Mos Espa after the final battle has been won. It is themes 11A, 11B, and the Boba Fett theme introduced in The Mandalorian that are used as leitmotifs and make up a large portion of the score. As seen in Table 2, the 11 themes together (A and B) occur 32 times over the course of the series while The Mandalorian Boba Fett theme is presented 30 times. These three themes are used throughout the series to serve as specific leitmotifs associated with the title character in each of the timelines. Additionally, each of these leitmotifs undergo significant melodic development that parallels the character’s personal development throughout the series. In alignment with Bribitzer-Stull’s three qualifications for leitmotifs, it is the mutation of themes—specifically the association of ascending sequential presentations of the themes with moments of triumph and character growth—that qualify each of the three themes as leitmotifs rather than themes or Idée Fixe. The following sections will consider the context and development of the two “past” leitmotifs (11A and 11B) and the “present” leitmotif (introduced in The Mandalorian).

Table 3

|

Theme |

Scene/Track |

|

3A |

“Stop that Train” |

|

“Aliit Ori’shya Tal’din” |

|

|

“Final Showdown” |

|

|

“A Town at Peace” |

|

|

3B |

“Aliit Ori’shya Tal’din” |

|

“A Town at Peace” |

|

|

3C |

“A Town at Peace” |

|

3D |

“The Ultimate Boon” |

|

“A Town at Peace” |

Appearances of Three Themes in The Book of Boba Fett.

Mutation of 11 Themes in Flashbacks

Not only can the 11B motif from Göransson’s “The Book of Boba Fett” be heard as an evolution of Williams’s original Boba Fett leitmotif, both 11B and 11A undergo significant mutation throughout the series in Shirley’s orchestration. All statements of 11A and 11B and their associated transformations are cataloged in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The remainder of this section will focus specifically on thematic statements developed through melodic sequence.

Table 4

|

Chapter; Timestamp |

Scene |

Transformation |

|

1; 3:07 |

Sarlacc Escape |

Melodic – Sequence |

|

1; 25:24 |

Desert Walk |

Timbral, Tempo 120, Harmonic |

|

1; 27:33 |

Desert Digging |

Bass only |

|

1; 28:52 |

Desert Digging |

Timbral, Tempo 120, Harmonic |

|

1; 32:35 |

Sand Beast |

Melodic – Sequence, Harmonic |

|

2; 19:38 |

Tracking Bike Gang |

Bass only |

|

2; 22:14 |

Post Fight |

Bass only, Tempo 138 |

|

3; 11:29 |

Bantha in Mos Espa |

Bass only |

|

4; 2:24 |

Bantha Ride |

Melodic, Timbral, Tempo, Extra measure |

|

4; 3:29 |

Bantha Ride |

Timbral |

|

4; 5:51 |

Bantha w/ Shand |

Bass only |

|

4; 12:55 |

Partners w/ Shand |

Tempo 96, Missing measure, Bass only, Timbral |

Appearances of Theme 11A in The Book of Boba Fett.

The 11A theme is the first theme heard in Chapter 1 of The Book of Boba Fett in association with Fett’s character. Rather than using the prototype of this theme heard in the title cue, Shirley chooses a descending sequential presentation of the 11A theme to accompany the first scene of the series (see Figure 9). In Fett’s first healing bacta-tank-induced “dream,” Fett emerges from the Sarlacc Pitt that he fell into during Episode VI – The Return of the Jedi. After almost forty years of viewers assuming that Fett was dead, the character punches through the sand to the triumphant melodic sequence that descends by half step and marks Fett’s victory and the start of the next chapter of his story.

Table 5

|

Chapter; Timestamp |

Scene |

Transformation |

|

1; 02:43 |

Sarlacc Escape |

Melodic – Sequence, Timbral |

|

1; 05:00 |

Tuscans Take Fett |

Harmonic |

|

1; 25:24 |

|

Timbral, Tempo 120 |

|

1; 28:56 |

Desert Digging |

Timbral, Harmonic, Tempo 110 |

|

1; 33:12 |

Sand Beast |

Melodic, Harmonic |

|

1; 33:40 |

Celebration |

Timbral, Melodic, Tempo 138 |

|

2; 14:18 |

Staff Training |

Tempo 118 |

|

2; 18:03 |

Tuscan Funeral |

Timbral, Tempo 82, Harmony |

|

2; 30:40 |

Train Heist |

Melodic – Sequence, Tempo 138, Meter |

|

2; 32:35 |

Train Heist |

Tempo – Augmented |

|

2; 33:45 |

|

Melodic – Sequence, Tempo 144 |

|

2; 36:07 |

Pike Negotiations |

Tempo 108, Harmonic |

|

2; 39:46 |

Lizard Dream |

Melodic – Sequence, Harmonic, Tempo 124 – Augmented |

|

2; 41:46 |

Post Lizard Dream |

Timbral, Tempo 82 |

|

2; 44:18 |

Tuscan Staff |

Timbral, Harmony, Tempo – Augmented |

|

4; 11:15 |

Shand Introduction |

Tempo 110 |

|

4; 16:22 |

Shand Introduction |

Tempo 82 |

|

4; 24:31 |

Slave 1 Reunion |

Harmonic, Tempo 152 |

|

7; 13:10 |

Tuscan Truth |

Tempo 100, Harmonic |

|

7; 45:47 |

Cad Bane Showdown |

Tempo 140 |

Appearances of Theme 11B in The Book of Boba Fett.

Figure 9a

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 1, Boba Fett’s Emergence from the Sarlacc Pit.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Figure 9b

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 1, Theme 11A as heard in Sarlacc Pit Escape Flashback.

After emerging from the pit, Fett is stripped of his armor by scavenging creatures called Jawas and taken as a prisoner by a nomadic desert tribe of Tuscan Raiders. The second moment marked by sequence is the moment that Fett begins shifting his position in the tribe from captivity to community. In this scene, Fett and another prisoner are chained to each other and are digging for water filled “black melons” under the watch of a young Tuscan and his Massiff—a fictional animal serving as a guard dog. As they dig, they are attacked by a sand beast which Fett kills to protect himself and the young Tuscan. It is this victorious moment where the 11A theme is presented as a looser melodic sequence that ascends a major third, a minor second, and an augmented second (see Figure 10). While Fett certainly proved in this scene that he could have killed the boy and fled, he chose to return to camp with the boy and the head of the beast. His decision to stay, after a few prior escape attempts, shows a shift in his attitude toward the Tuscans. Due to Fett’s protection of the young Tuscan, the tribe begins to change their view of Fett as well, trusting him enough to remove his chains and begin training him in their way of life.

The third shift in Fett’s Tuscan development is the move from tribe membership to leadership. A train running through the Tuscans’ home continues to terrorize the tribe, shooting down Tuscans and the Banthas they ride every time it crosses the “dune sea.” In defense of his new family, Fett organizes and leads a successful attack on the train. Fett is no longer staying with the Tuscans to survive, he has become a teacher, leader, and defender of the tribe. The mission to stop the train is the first that we see Fett in this leadership role and his victory is underscored by the sequential presentation of the 11B theme, first when Fett is running on top of the train at the height of the train heist scene, and again as Fett uses his new Tuscan staff to stop the train. Figure 11 shows the melodic sequence that underscores the train heist scene. This sequence ascends a whole step between each of the three iterations of the theme.

Figure 10a

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 1, Fett’s triumph over the Sand Beast.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Figure 10b

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 1, Theme 11A as heard in Fett’s Victory over the Sand Beast.

Figure 11a

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 2, Boba Fett Leading the Train Heist.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Figure 11b

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 2, Theme 11B as heard in the Train Heist.

Mutation of The Mandalorian Fett Theme in the Present Timeline

All three sequential statements of the 11 themes mentioned in the previous section, and in fact 31 of the 32 statements of the 11 themes, occur during flashback scenes and are thus leitmotifs for Fett’s past. While the 11 themes are developed and used as leitmotifs for Fett in flashbacks to signify significant moments of character development in his Tuscan Raider story, The Boba Fett leitmotif from The Mandalorian is used almost exclusively—29 of 30 statements—in the present-day timeline. All statements and transformations of this theme can be seen in Table 6. This section examines a significant sequential mutation of this theme in the Mos Espa present-day timeline.

Table 6

|

Chapter; Timestamp |

Scene |

Transformation |

|

1; 00:54 |

Fett in Bacta Tank |

Melody only, Tempo 98 |

|

1; 17:32 |

Walking the Streets |

Tempo 118 |

|

1; 22:35 |

Street Fight |

Harmonic, Tempo 115 |

|

2; 04:16 |

Trip to the Mayor |

Timbral, Tempo 100 |

|

2; 12:18 |

Twin Visit |

Tempo 100, 3/4 |

|

2; 13:36 |

Twin Visit |

Timbral, Tempo 100, 3/4 |

|

3; 05:48 |

Recruiting Family |

Tempo 130, Harmonic, Timbre |

|

3; 08:33 |

Recruiting Family |

Tempo 98, Harmonic, Bass only |

|

3; 20:14 |

Rancor Gift |

Melodic, Tempo 130 |

|

3; 22:05 |

Rancor Gift |

Tempo 126 |

|

3; 23:11 |

Rancor Gift |

Tempo 128 |

|

3; 27:00 |

Rancor Gift |

Harmonic (Bass Sequence) |

|

3; 32:01 |

Major-Domo Chase |

Tempo 140, Bass only |

|

3; 33:19 |

Declaring War |

Tempo 140, Melody only |

|

4; 20:57 |

Saving Slave 1 |

Bass only, Timbral |

|

4; 24:31 |

Saving Slave 1 |

Harmonic, Tempo 152 |

|

4; 25:38 |

Biker Revenge |

Tempo 130, Melodic |

|

4; 32:27 |

Talk with Shand |

Tempo 96 |

|

4; 32:51 |

Flash to Throne |

|

|

4; 38:21 |

Recruiting |

Tempo 140, Bass only |

|

4; 39:35 |

Recruiting |

Melody only, Melodic |

|

4; 42:27 |

Recruiting |

Tempo 152, Melodic, Harmonic |

|

5; 46:51 |

Mando Hired by Fett |

Tempo 158, Melodic only |

|

6; 26:47 |

Mando Arrives |

Melodic, Harmonic, Tempo 124 |

|

7; 9:40 |

Plan of Attack |

Tempo 136, Melody, only, Harmonic |

|

7; 23:39 |

Pike Shootout |

Tempo 136, Melodic, Timbral |

|

7; 27:40 |

Wookiee Save |

Tempo 136, Bass only |

|

7; 36:04 |

Riding Rancor |

Tempo 130, Timbral, Melodic, Harmonic |

|

7; 37:06 |

Riding Rancor |

Tempo 130, Bass with Mando theme, Harmonic |

|

7; 42:20 |

Riding Rancor |

Tempo 144, 7/8, Melodic, Timbral, Harmonic |

Appearances of Boba Fett Theme from The Mandalorian in The Book of Boba Fett.

In the final chapter of the series (Chapter 7), the timelines have caught up to one another and Boba Fett fights alongside his new crime family and Din Djarin to reclaim the city from the mayor and the Pyke Syndicate. Fett discovers that the Pykes are responsible for the murder of his Tuscan tribe which adds an undertone of avenging to his mission to retake the city. In the final battle for Mos Espa, Fett rides his pet Rancor for the first time through the city to defeat the droids that are attacking. The action sequences leading up to Fett’s Rancor ride are in a quick 7/8 which leads to the rhythmic modification of the 4/4 theme to fit into a non-isochronous meter. Figure 12 shows this mutation of Fett’s present-day theme. The main idea begins a repetition up a step (a major second in the melody and a minor second in the harmony below) but is modified to have a different ending. In this moment, Fett’s riding of the Rancor— a feat that the previous leaders of the city never accomplished—serves as a declaration of authority over all of Mos Espa and the culmination of the character arc that brought him to the throne in the first place. Through each of the key moments in Fett’s story—his survival, his shift from captivity to community, his rise to Tuscan leadership, and his successful claiming of the Mos Espa crime syndicate—we hear themes developed through melodic sequence, often ascending to parallel Fett’s own personal rise to power.

Figure 12a

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 7, Boba Fett Riding his Rancor.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Figure 12b

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 7, Fett’s “Present-Day” Theme.

Timeline Exceptions and New Motivic Associations

With two exceptions, every Boba Fett theme from The Mandalorian occurs in the present-day timeline and as previously noted, every 11A or 11B theme is situated in a flashback scene. This section considers both exceptions, the significance of these scenes, and the new layer of meaning they imbue into Fett’s leitmotifs. The first exception occurs in Chapter 6 when, during a flashback, Fett and Shand retrieve Fett’s ship—the Slave 1. Even though this is a flashback, since the Slave 1 is a part of Fett’s current life as a Crime Lord in Mos Espa, this scene involving the ship is scored with both an 11 theme—a nod to the flashback—and the present-day theme upper-neighbor motive—a recognition that the ship is part of Fett’s present timeline and perhaps also an indication that the timelines are catching up to each other.

Figure 13

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 6, Fett and Shand Reclaim the Slave 1.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

The second notable exception occurs in the season finale. In Chapter 7, Boba Fett has two primary triumphant moments, both in present day. The first is his riding of the Rancor mentioned in the previous section. The second is his duel with a rival gun for hire—Cad Bane. Bane is working for the Pykes and is the one to deliver the news that it was the Pykes who slaughtered Fett’s Tuscan family and then staged a cover up. Fett and Bane’s duel is not just for the city of Mos Espa in whose streets they fight, it is also the culmination of Fett’s Tuscan story line—justice for his tribe is finally in reach. While this scene is in the present-day timeline, Fett does not rely on his Mandalorian armor or modern weapons to win the battle. Instead, he uses his Tuscan training in hand-to-hand combat and his Tuscan-made staff—the same staff he used to lead the Tuscans to victory in the train heist—to emerge victorious over Bane. It is Fett’s past that equipped him for this moment and allowed him to tie up the final loose end in his past timeline. Because of this, the scene uses not the present-day theme introduced in The Mandalorian, but the 11A theme associated with Fett’s past and his Tuscan tribe.

Figure 14

The Book of Boba Fett, Chapter 6, Fett Triumphs over Cad Bane.

© Fairview Entertainment; Golem Creations; Lucasfilm; Walt Disney Studios

Because of the two notable exceptions detailed in this section, I propose that the present-day theme is better identified as the “Crime Lord” theme and that the 11A and 11B themes are not “flashback” or “past” themes, but “Tuscan” themes. Throughout the series, Shirley effectively develops three different leitmotifs for Boba Fett. Two—11A and 11B—that are musical representations of Fett’s dreams and reminiscences of his past personal growth and his familial connection with the Tuscan Raider tribe, and one that signifies Fett’s present-day conquest of Mos Espa and his development of a new crime family.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Göransson and Shirley’s musical addition to the Star Wars universe can be heard as both a reference to the past and a path into the future of the franchise. Their work in The Book of Boba Fett honors Williams and the original Star Wars trilogy through the quotation and evolution of pre-existing leitmotifs that invoke viewer nostalgia. However, the full score for the show is far from derivative and contains much more than these recycled materials. The addition of new leitmotifs for the leading character and the innovative deployment of these motifs throughout the show demonstrate how Göransson and Shirley are stepping away from tradition into a new era of Star Wars music. The first display of this progress is the sequential development of leitmotifs throughout all seven chapters to parallel the main character’s own personal development as he overcomes obstacles, forges relationships, and rises to power. The second and more significant innovation is Göransson and Shirley’s choice to use two different sets of Boba Fett leitmotifs. These two sets of aurally distinct cues represent not only the complexity of the character and his unfolding backstory, but also aurally reinforce the non-linear narrative of each chapter of the show. This differentiated musical representation of the character in each timeline not only stands apart from other content in the Star Wars franchise it also represents a departure from the typical scoring practices of non-linear science fiction and fantasy television shows.

As mentioned at the start of this article, Göransson and Shirley are but two of many composers adding their voices to the music of the Star Wars franchise alongside Williams. This study is far from exhaustive in scope and encourages the future exploration of scoring practices among the new generation of Star Wars composers. Star Wars is far from the only franchise adapting existing content and/or developing new content for various audio-visual media formats, nor are they the only franchise passing the baton to new writers, directors, and composers. This opens yet another door for future study of such adaptations, considering both their acknowledgement of the music from the source materials and their unique additions and innovations in the new composers’ voices. For each such franchise, reaching a new generation of fandom requires change, including the addition of new voices to the scoring process. This inevitable evolution of scores and scoring practices should be studied and celebrated since, as Shmi Skywalker so eloquently stated, “You can’t stop change any more than you can stop the suns from setting.”11