“Obviously, no one’s going to write music that is as great as what John Williams did.”

Ludwig Göransson (Grobar 2020).

The Star Wars franchise, created by George Lucas in the 1970s, has become a cultural phenomenon that has spanned generations and captivated audiences on a global scale. Central to its enduring appeal is not only the compelling storytelling and iconic characters but also the memorable and evocative music composed by John Williams. Williams’ contributions to the series cannot be overstated, providing the symphonic soundscape that has defined the fictional universe for over four decades. Such is the strength of the symbiotic relationship between the films and Williams’ music that the trailer was deemed “laughably bad”, with one of the reasons (in hindsight) being that Williams’ as-yet-unwritten musical score did not accompany the “highly generic” shots of “dorky robots” (Guynes and Hassler-Frost 2018, 15). The tone, argues Jenkins, would have been very different had Williams contributed the music to the preview. Williams’ score is now generally considered one of the finest in cinematic history, comprising dozens of leitmotifs, functioning in a straightforward, efficient manner narratively, and recorded by a world-leading ensemble in the London Symphony Orchestra (Audissino 2014, 73). In other words, composed in the tradition of classic cinematic scoring. Williams’ scores have enjoyed extensive, eclectic academic critique in film musicological circles, ranging from approaches such as the neo-classical lens of Kalinak (1992, 184–202) to the discussion of Williams’ music as a signifier of worship and religion (Thornton 2019, 87–100).

However, as the franchise has expanded in the twenty-first century with spin-off series and films, a new question has arisen: what does a galaxy far, far away sound like when John Williams’ iconic musical presence is absent? While John Williams’ scores have become synonymous with the original, prequel, and sequel Star Wars trilogies (Episodes 1–9), recent developments in the franchise have seen the emergence of alternative composers tasked with shaping the musical identity of new Star Wars content, both feature films and anthology series released on the streaming service Disney+. To provide a comprehensive analysis of this evolution, I scrutinize the creative choices made by composers as they navigate the delicate balance between honouring the original scores and forging new musical paths in a franchise known for its iconic, ubiquitous musical themes such as “The Imperial March” and Force theme, among others.

This investigation extends beyond a mere examination of individual compositions. I consider the broader implications of these musical choices on the Star Wars franchise, addressing questions of musical continuity, the role of Williams nostalgia, and the impact on audience engagement. In doing so, I aim to shed light on the dynamic relationship between composers, filmmakers, and the enduring legacy and identity of Star Wars.

Furthermore, this article undertakes a succinct analysis of the fan reception of Star Wars spin-off productions, specifically focusing on online reviews and comments made in online discussions. The examination critically investigates the way the omission of Williams’s musical scores impacts the perception and appraisal of these spin-offs within the fan and critical communities. This article seeks to shed light on the extent to which John Williams’s musical contributions have become integral and critical to the identity and experience of the Star Wars franchise, and how their absence may influence the overall reception and evaluation of derivative works within this cinematic universe.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the departure, or exclusion, of a major composer from a franchise is not a novel occurrence in the realm of cinematic music. Instances such as the Jaws (Steven Spielberg, Jeannot Szwarc, Joe Alves, Joseph Sargent, 1975-1987), Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, Joe Johnston, Colin Trevorrow, J. A. Bayona, Gareth Edwards, 1993-2025), and Harry Potter (Chris Columbus, Alfonso Cuarón, Mike Newell, David Yates, 2001-2011) film series have all witnessed sequels in which John Williams’s musical prowess was either entirely absent from the credits or adapted by different composers to varying degrees. The particular significance of Star Wars and the impetus behind composing this article necessitate examination. One can argue that Star Wars holds a unique position as a cinematic score that reintroduced the neoclassical style of composition and reinstated symphonic music to the science fiction genre. Kathryn Kalinak (2001) aptly characterizes The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) as a blend of “classical meets contemporary” while Emilio Audissino (2014) delves into Star Wars as an oppositional score, countering prevailing trends and carving out a revolutionary path. John Williams’s score for Star Wars was groundbreaking, not necessarily in its musical complexity, as it drew heavily from the late 19th-century symphonic tradition and was occasionally labelled as embracing corny Romanticism. Its groundbreaking nature stemmed from the unparalleled, virtually unbreakable connection it forged between the sonic and visual elements of cinema. Williams’s music became synonymous with Star Wars, and conversely, Star Wars became inexorably intertwined with Williams’s music.

Not too long ago, the idea of a Star Wars production without John Williams was simply unfathomable. Yet, when the much-anticipated film Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Dave Filoni) hit screens in 2008, it didn’t take long for keen-eyed critics and passionate fans to zero in on a conspicuous absence—John Williams. The verdict was not favourable.

One must empathise with Kevin Kiner, the composer tasked with composing The Clone Wars. In a review found on FilmTracks, the name of John Williams makes an astonishing appearance—no less than thirty times, to be exact (“Star Wars: The Clone Wars” 2008). More intriguingly, these mentions are often tinged with a sense of yearning, as if to accentuate the unavoidable fan opinion that Kiner’s music, while commendable, falls short of the iconic John Williams standard. For instance, the review laments that “purists that swear by Williams’s original six scores will be driven nuts by Kiner’s changes” (“Star Wars: The Clone Wars” 2008). Mercifully for Kiner, he returned to score the Disney+ series Ahsoka in 2023, and produced a rich, forward-thinking score that received much more favourable reviews.

Critically, The Clone Wars film found itself languishing in the shadows, often described as a pale shadow of George Lucas’ illustrious franchise1. This sentiment was palpably reflected in its meagre 19% rating on the revered Rotten Tomatoes review website (“Star Wars: The Clone Wars” 2023). Arriving on the scene a mere three years after the divisive prequel trilogy, it appeared as though the future and reputation of the Star Wars galaxy teetered on the edge of uncertainty. The fanbase, critics, and even actors from the original films, long disenchanted with what they perceived as a dip in the franchise’s quality during the prequel era, had openly revolted, resulting in nearly a decade of simmering unrest within the community (Child 2013). In 2015, the eagerly anticipated Episode VII – The Force Awakens (J. J. Abrams) made its debut, marking a perceived welcome return to form for the Star Wars franchise. A musical paradigm shift occurred with the release of a film just a year later, with the introduction of the first major Star Wars motion picture without John Williams at the musical helm.

Rogue One (2016)

In 2016, the inaugural instalment of the much-discussed Star Wars anthology film series arrived on the scene—Rogue One (Gareth Edwards). As Gerry Canavan highlights in a chapter on the so-called “New Star Wars”, speculation in the fandom was rife, and music was one of the primary discussion points. Questions were asked about whether the film would use music from the original trilogy, or whether it would even use a Williams style orchestral score at all (Canavan 2018, 281).

Michael Giacchino’s original score for Rogue One served as an homage to the stylistic musical heritage of the Star Wars cinematic universe. Within the context of the film, Giacchino incorporated allusions to Williams’s Skywalker Saga compositions, encompassing both subtle and overt manifestations of leitmotifs from the original Star Wars films. This judicious integration of established motifs contributed to an enhanced sense of resonance and nostalgia within the Rogue One soundtrack, facilitating a seamless convergence of the standalone narrative with the broader Star Wars cinematic corpus. However, there were also many musical departures from Williams’s style.

Giacchino discussed his compositional approach to the film as being one of freedom, claiming that it gave him a chance to “play in a world” that he loved, but also that he did not feel compelled to use any music that had come before; namely Williams’s (Brooks 2017). The composer continued that he wanted it to ‘feel’ like a Star Wars movie, and tried to take what he described as the Williams DNA of the original films into Rogue One (Brooks 2017). Playfully, Giacchino admitted that he wanted to stay relatively close to the Skywalker Saga sound, remarking that he did not want to say “Hey, I’m going to do a whole new thing with this and now it’s going to sound like heavy metal!”, but rather that he had audience, brand, and familiarity in mind (Brooks 2017).

Rogue One’s first notable departure from Star Wars tradition was apparent from its opening moments. Absent was the iconic opening crawl, accompanied by John Williams’s famous fanfare. Instead, the film greeted its audience with a singular chord, followed by a woodwind interlude that bore a discernible resemblance to Williams’s Star Wars back catalogue as the camera ascended. A more striking deviation from Williams emerged when the Empire, a central, sinister presence in the Star Wars narrative, did not enter to the familiar strains of the “Imperial March”, one of the franchise’s—and cinema’s—most renowned leitmotifs. While the harmonies hinted at the “Imperial March”’s influence, Frank Lehman’s meticulous Star Wars thematic catalogue confirms that Rogue One introduced not one, but two new themes for the “Imperials” (Figures 1 and 2).

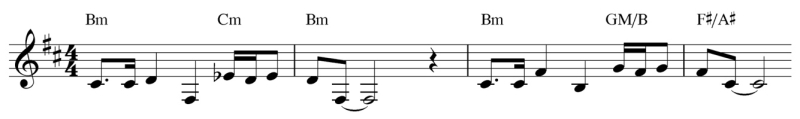

Figure 1

Rogue One, “Imperials 1”, a sinister theme representing the Empire, introduced early in the film (00:58) (Lehman 2023).

Figure 2

Rogue One, “Imperials 2”, the second, more powerful, theme for the Empire (22:23) (Lehman 2023).

Although the initial scenes of the film don’t feature any of John Williams’s music verbatim, his influence can be unmistakably felt. This influence becomes immediately apparent during the aforementioned woodwind interlude in space, followed by the title sequence after a long, suspense.ul cold open to the film. Much like the renowned “STAR WARS” title reveal, the film’s title is revealed with a sudden cut to “ROGUE ONE” in large, prominent font against a background of space. Within this moment, Giacchino reveals the ‘Hope’ leitmotif (Figure 3), which itself commences with a rising fifth—the same musical interval that opens the iconic Star Wars main theme. This musical choice is noteworthy and establishes stylistic conformity, as it is one of the intervals frequently utilized by Williams in some of his most revered compositions such as the main themes for Superman (Richard Donner, 1978), E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982), the Indiana Jones franchise (Steven Spielberg, James Mangold, 1981-2023), and Jurassic Park.

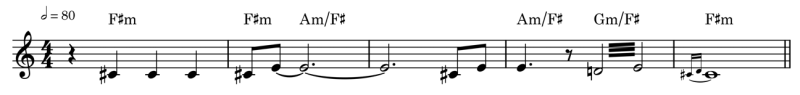

Figure 3

Rogue One, “Hope”, a rising theme of fifths and sixths that offers hope to the protagonists (07:30) (Lehman 2023).

There are several prominent Williams cues that appear in Rogue One. The first of these is the rebel fanfare. This short, two-bar brass cue appears when references to the original Skywalker Saga films are made, or when the rebels are amassing or fighting in a particularly heroic fashion in the narrative. One noteworthy occasion where this happens is when Yavin IV is visited for the first time. This jungle covered moon was a prominent location in Star Wars (1977) as the base for the Rebel Alliance, and with Rogue One being an immediate chronological prequel to the first film in the original trilogy, the use of the visual setting and Williams’s music ensures that it is Rogue One that commences the exposition of Yavin IV as a key geographical focus point in the grand narrative of the Star Wars universe.

The Force theme makes several appearances in Rogue One, although not always in the expected contexts. The first unexpected instance occurs on Yavin IV as Jyn Erso, Cassian Andor, and K-2SO depart for Jedha. While the Jyn motif is initially heard as their ship departs, the music then undergoes a transformation into a slightly more contemplative yet dramatic rendition of the Force theme. This is intriguing, as there are no Force-sensitive characters in this sequence, and there are no references to Jedi before, during, or after this scene. A visually similar sequence occurs in the broader Star Wars narrative when the Rebel fleet departs the Rebel Alliance base to attack the Death Star. However, in this case, the Force theme is absent, even though Luke Skywalker is piloting one of the ships. In the films utilising the music of John Williams, leitmotifs are typically incorporated either explicitly or with strong implicit connotations. The inclusion of the Force theme in Rogue One momentarily disrupts the typically stringent connection between visual and musical elements found elsewhere in the original Star Wars films. Other instances of the Force theme’s use in the film are more straightforward, with the music alluding to off-screen characters. For example, as Mon Mothma speaks to Bail Organa, referring to “your friend, the Jedi”, the Force theme softly underscores the dialogue. The Jedi in question is Obi-Wan Kenobi, who is currently in hiding on Tatooine before Luke’s eventual discovery of him in Episode IV: A New Hope. Organa then indicates his need for assistance in finding Obi-Wan, to which he responds that he will bring someone he trusts with his life, referring to his adopted daughter, Leia. At this point, the Force theme underscores both Obi-Wan and Leia as Force users, and whilst neither character is named in Rogue One, the music offers a sonic clue as to their identity.

The final instance of the Force theme in the film occurs at the conclusion when the Death Star plans are handed to a CGI recreation of Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia, setting the stage for the opening of A New Hope. In a film that does not primarily focus on Jedi or the Force to a significant extent, the inclusion of the Force theme serves as a compelling link to John Williams’s scores for the original narratives. It anchors viewers in the Star Wars universe, even when surrounded by ostensibly unfamiliar characters.

Arguably the two most renowned themes from the Skywalker Saga, the main theme and the “Imperial March”, are teased at points in Rogue One, and both make short but effective appearances at key narrative moments. The main Star Wars theme makes a fleeting appearance two thirds of the way through the film, when C3PO and R2D2 are foregrounded for ten seconds. C3P0 remarks incredulously “Scarif?! They’re going to Scarif?! Why does nobody ever tell me anything, R2?” Underneath this dialogue, a frivolous woodwind rendition of the main theme is heard. This is a rare instance in a spin-off production of two Williams themes appearing concurrently, as it is immediately prefaced by the Force theme.

The second instance of the main theme serves to maintain consistency across the Star Wars film anthology: the final credits. The familiar blue text against a starry backdrop is accompanied by the same arrangement of the main theme that Williams used in all nine Skywalker Saga films. This sonic embrace reassures the audience that, despite the absence of Williams and the incorporation of a new musical direction in the film, Rogue One is undeniably a Star Wars instalment.

The “Imperial March” assumes a prominent role in the movie, making its presence felt on three distinct occasions. The first appearance, albeit fleeting, stands out as arguably the most innovative. A defected Imperial pilot stands before Saw Gerrera, a Rebel extremist, who is now in a state of frail health due to severe lung and leg injuries, relies on a respirator and a life-preserving pressure suit. When Gerrera speaks to the former Imperial pilot through his respirator, a moment of palpable tension ensues. The ex-Imperial pilot’s terror is briefly underscored by a timpani melody, accentuating the first few notes of the “Imperial March”. Here, Vader’s enduring influence on the pilot and the prevailing sense of fear in the Star Wars universe are symbolized by the artificial, assisted breathing sound. The solitary timpani, lurking in the audio mix, offers a sinister sonic reference to a character lightyear away but whose signature sound invokes terror within the diegetic world and, via the timpani, in the non-diegetic realm.

The second appearance of the “Imperial March” unfolds during a pivotal showdown between Director Krennic and Darth Vader within the impenetrable confines of a fortress tower. Commencing with the “Imperial 6a” motif, as identified by Lehman (2023), the composition seamlessly transitions into a slow, brooding rendition of the “Imperial March” (Figure 4).

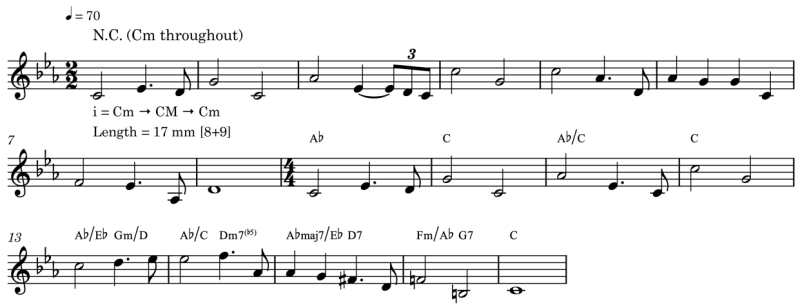

Figure 4

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, “Imperials 6a”, the main antagonist theme prior to The “Imperial March” being composed for the next film (05:42) (Lehman 2023).

This transformation is marked by the lower brass taking the melody, lending an air of sinister gravity to the scene. The final four bars of this theme return as Vader purposefully departs while Director Krennic barely hangs on to his life, having been ensnared by the menacing grip of a force choke by Vader.

The third and final appearance of the “Imperial March” occurs when Darth Vader ruthlessly engages a group of Rebel forces aboard a spacecraft, who are valiantly striving to deliver the Death Star plans to Princess Leia. Vader’s imposing presence and murderous actions are underscored by a slowed down harmonic hint at the “Imperial March”, with dramatic, climactic choral chords accompanying a terrifying vision of Vader at his most furious and aggressive. The plans, a crucial narrative element, slip from his grasp and are concealed within an escaping shuttle. A solitary bar of the “Imperial March” plays at this pivotal moment, before being briefly replaced by an unrelated fanfare as Vader looks out into space in anger.

In terms of overall style, a noteworthy departure from John Williams’s signature lies in the film’s romanticization or sentimentalisation of the Empire as it nears its conclusion. This shift does not, however, diminish the Empire’s sense of malevolence and authority. Instead, it introduces a striking departure from the visual and sonic aesthetics typically associated with Lucas and Williams. As Cassian Andor and Jyn Erso transmit the Death Star plans from the surface of Scarif, a four-minute musical composition titled “Your Father Would Be Proud” takes centre stage. This musical cue accompanies significant moments of dramatic climax in the film: the Death Star’s arrival in orbit, the Empire’s decision to fire upon the surface, the successful transmission of the Death Star plans, and the tragic demise of Andor and Erso. In a John Williams score, one might expect the “Imperial March” to underscore the menace of this weapon of mass destruction, combined with a Wagnerian approach utilizing leitmotifs and dramatic elements to build suspense and characterization. However, Michael Giacchino’s composition follows a different path, running consistently throughout these moments and delivering an unexpected touch of poignancy. This is particularly evident when the Death Star makes its appearance, marked by a tender and delicate woodwind passage that descends from a diminished fifth to a major third. The juxtaposition of this soft, sensitive, small-scale woodwind ensemble with a colossal, destructive weapon of unimaginable scale is striking in its emotional impact, effect, and its divergence from the stylistic elements traditionally associated with Williams.

The challenge of establishing a familiar connection with a Star Wars film, particularly the inaugural feature-length spin-off, was amplified by the presence of a new director, a different musical score, and the introduction of new characters. In this initial evaluation, the absence of the customary musical and thematic elements may have engendered a sense of musical estrangement among the audience. The YouTube comments section serves as a compelling resource for gauging public and fan responses to media, including films and music. On the official DisneyMusicVEVO video featuring the cue “Your Father Would Be Proud”, there are over 6,000 comments as of 9 February 2024, accompanied by nearly 7 million views2. Among these comments, 66 make mention of John Williams, while 104 acknowledge the actual composer, Michael Giacchino. User David Andrés Rojas succinctly encapsulates the core issue surrounding fan reception to the new sonic elements of Star Wars with the statement, “Not John Williams, but still amazing”. These six words effectively elucidate the central theme of this article to such an extent that they could easily serve as its title or epigraph.

This apparent reluctance to disassociate from John Williams is also conspicuous in web reviews of the score. In one review, Williams is mentioned ten times, whereas Giacchino’s name appears slightly over 40 times (Heidkamp 2017). For every four occurrences of the actual composer’s name in the review, Williams’s name surfaces, despite his lack of direct involvement in the film. Furthermore, the language used in these reviews conveys a desire to retain the stylistic and aesthetic elements associated with Williams. The review suggests that Giacchino faced “immense” pressure and goes on to claim that “the style is unmistakably Williams”, the score is “clearly imbued with the spirit of Williams”, and that Giacchino “relies on” and “faithfully adheres to Williams” (Heidkamp 2017). This review is not an isolated example of this trend, as another one mentions Williams 23 times, with eight instances occurring in just two brief paragraphs. Again, the focus is on the pressure of new composers to be “respectful” to Williams, be “influenced” by Williams, and to employ “Williams-esque” or “Williams-style” orchestration (Broxton 2016).

However, as this article will elucidate with subsequent examples, a reassessment over time reveals a gradual shift in perspective amongst the Star Wars fanbase, eventually dispelling the initial shock of musical disconnect, and ultimately acknowledging and growing fond of a new, exciting musical identity and period for Star Wars screen productions.

Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018)

The acquisition of the Star Wars rights by Disney+ represented a significant milestone in the media and entertainment industry. In 2012, The Walt Disney Company, under the leadership of CEO Bob Iger, purchased Lucasfilm Ltd. for approximately $4.05 billion, a move that included the rights to the Star Wars franchise. This acquisition marked a strategic decision by Disney to expand its content portfolio and capitalize on the enduring appeal of the Star Wars universe. By securing these rights, Disney+ gained the ability to leverage the vast Star Wars catalogue, encompassing both the original Skywalker saga of nine films and an array of spin-off series and films. Subsequently, Disney+ became the exclusive streaming platform for Star Wars content, offering subscribers access to a rich and ever-expanding galaxy of storytelling, and positioning itself as a key player in the streaming wars.

Solo: A Star Wars Story (Ron Howard, 2018) serves as a prequel to the original trilogy, offering a deeper exploration of the origins and early adventures of the roguish character, Han Solo (played by Harrison Ford in the Skywalker Saga). The narrative revolves around the young Han Solo, played by Alden Ehrenreich, as he encounters canonical characters such as Chewbacca and Lando Calrissian, as well as his experiences with criminal syndicates, including the infamous Crimson Dawn. These adventures provide insights into the development of Han’s character, his moral compass, and the friendships and rivalries that would shape his Skywalker Saga character.

John Powell was selected to compose the music for Solo, with the understanding that John Williams would contribute the main theme. Consistent with the prevailing theme in this article, which revolves around the notion of composer anxiety and pressure, Powell humorously referred to his initial encounter and collaboration with Williams as a “mixture of humbling and frightening.” He likened their working relationship to that of a master and apprentice, drawing on Star Wars tropes, and described the experience as akin to being back in college (Baver 2018). Whether this was jovial self-deprecation or a genuine sense of being overwhelmed, Powell’s interviews suggest a profound reverence for Williams. He characterized Williams as possessing a level of mastery that “simply doesn’t exist anymore” and drew comparisons to iconic composers like Brahms, Sibelius, and Tchaikovsky (Baver 2018). Additionally, Powell articulated his personal criteria for success on Solo, expressing his desire to “simply come up with something as exceptional as John Williams” (Star Wars News Net 2021). While he acknowledged a tendency to draw inspiration from Williams throughout his career, admitting that he “probably stole from John” consistently and even when he wasn’t consciously doing so, Powell was steadfast in emphasizing the importance of differentiating his work from the original music (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). Despite his self-deprecating confession that at times he felt like he was “being me, but doing an impression of John” during the scoring of Solo (The Resistance Broadcast 2021), Powell explained that he naturally incorporates his own distinct style into his work. He stated, “I can’t help but be a bit different”, and clarified that, even though he is “forever influenced by John Williams”, he’s not inclined to sound exactly like John. Powell acknowledged, “I have my own peculiar methods of doing things, and they infuse everything with my unique touch” (The Resistance Broadcast 2021).

Adding another layer of complexity to the situation, Powell mentioned having full access to Williams’s original Star Wars compositional sketches, which he described as “hellish”. He reiterated that he felt a sense of “I am not worthy” while collaborating with Williams (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). In the early stages of the process, Williams and Powell had a meeting during which Williams played two nascent themes for Han on the piano. Powell noted that once Williams had completed these themes, he felt more confident in progressing with the remainder of the score. Powell likened this phase to “figuring out the puzzle” of what Solo’s musical identity would entail (Baver 2018). The score for Solo thus follows a similar path to Rogue One, as it combines an "in the style of Williams" approach with innovative musical directions that introduce fresh elements to the Star Wars universe. In Powell’s own words, his aim was to “honour” Williams’s style while crafting a score that offered compelling and unique interpretations for various musical situations, both within the story’s universe and in its broader context (Baver 2018).

Set 10–13 years BBY (before the Battle of Yavin), Solo’s timeline coincided with the Empire’s ascent to its initial power, where Emperor Palpatine and the newly appointed Darth Vader held sway over the galaxy with an iron grip3. Arguably, the use of the “Imperial March” in Solo stands out as one of the most innovative among all the spin-off films and series. Not only do we encounter a ground-breaking diegetic rendition of the leitmotif, but when it appears in its original form elsewhere, it departs from glorifying the Empire’s might to offer a grittier depiction. A thirty-second sequence near the beginning of Solo ignited a stir of both positive and negative reactions within the fan community. As Han searches for an escape from Corellia, he realizes that his only option at the spaceport is to hastily enlist in the Empire as a pilot. Bluntly informed that he’s better suited for the infantry, he officially becomes an Imperial recruit. However, it’s a piece of diegetic music that sparks this decision for Han. While cowering behind some boxes in the spaceport, Han looks up and observes a propaganda recruitment video playing on a large billboard screen. The voiceover emphatically declares, “Be a part of something; join the Empire! Explore new worlds. Learn valuable skills. Bring order and unity to the galaxy. Be a part of something; join the Empire!” Powell undertook a remarkable initiative in this scene, one that upended the established musical canon of Star Wars by embedding the “Imperial March” into the diegesis, integrating it into the Star Wars universe for the first time in live-action media4.

In this instance, the “Imperial March” is arranged in a major key, a departure that evokes the orchestration and stylistic elements of Edward Elgar. This choice was deliberate on Powell’s part. He revealed that the use of this iconic leitmotif was a “last-minute gag” that drew inspiration from Elgar’s Proms favourite, Land of Hope and Glory. Powell explained that he used this music “to make an anti-British Empire joke”, recognizing that Williams is a notable admirer of Elgar. Powell even remarked to his orchestrator, “We can really make this [cue sound like] Elgar, can’t we?” (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). Interestingly, when Williams initially heard the major key, playful arrangement on the soundtrack, he wasn’t a fan. However, upon experiencing it in the film’s context, he grew to appreciate it (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). The inclusion of the “Imperial March” within the diegesis introduces a layer of complexity to its reception and signifies the first musical tribute from spin-off composers that bridges the gap, transitioning from the non-diegetic realm to an integral component of the musical culture within the Star Wars universe.

Non-diegetic applications of the “Imperial March” in the spin-off series are consistently intriguing. In Solo, a non-diegetic, orchestral rendition follows just moments after the quasi-Elgar diegetic propaganda soundtrack. The narrative visual transitions to a scene evocative of World War II films, marked by a time jump that reads “Three Years Later”. Here, we find Han amidst a chaotic battle as part of the Imperial infantry. The setting is bleak, shrouded in darkness, smoke, mud, and disorder, starkly devoid of the dark glamour and efficiency typically associated with the Empire. Death and destruction surround them, with one soldier objecting, “this ain’t a quick job—it’s a war!” The “Imperial March” is briefly heard but remains subdued and is abruptly cut short. This aesthetic shift, as later embraced by the spin-off series Andor on Disney+, presents the Empire in a raw, unfiltered light. The pristine, imposing pragmatism of Vader and Palpatine from the Skywalker Saga seems distant, and the stark reality emerges of how the Empire expanded its dominion across the galaxy: through invasion, death, and despair. In this particular scene, much like the inspired use of the leitmotif during Vader’s death in Return of the Jedi, the “Imperial March” serves as an elegy or lament, rather than a display of power. The march melody is employed judiciously in Solo, but various other Imperial motifs make their presence felt. This includes the aforementioned 6a motif and the sinister four-note Death Star motif, which appear at different junctures in the film. From a continuity standpoint, this musical choice aligns with the pre-A New Hope timeline, as the “Imperial March” was notably absent from A New Hope having not yet been composed (Lehman 2023).

The musical references to pre-existing Skywalker Saga cues also extend to other non-diegetic uses of John Williams’s music, and nowhere is this better illustrated than in the journey into the Maelstrom aboard the Millennium Falcon, where Han famously (and truthfully) completed the Kessel run in under twelve parsecs. In this scene, Powell’s extensive musical composition combines original pieces with what he aptly describes as “lots of references to other movies”, essentially integrating past musical material (Baver 2018). One such example of incorporating existing material is the popular “Asteroid Field” cue from The Empire Strikes Back, a revered cue within the Skywalker Saga. Powell also skilfully weaves in the Rebel Fanfare, the TIE Fighter attack, Chewbacca’s theme, the main Star Wars theme, and Han’s new motif from Solo into this exhilarating musical collage of cues. The striking similarities in visuals and narrative result in a deliberate sonic callback to the original trilogy. The musical build-up in this scene is so frenetic that Powell jokingly remarked on the challenges the orchestra faced while performing it (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). At the climax of this sequence, a new creature is introduced: the immense summa-verminoth. This kilometers-long tentacled beast is accompanied by an entirely new instrument in the Star Wars universe, the vuvuzela. Powell drew inspiration from the riotous noise made by these instruments at the 2010 South Africa football World Cup and characterized their sound as “a very unpleasant raucous noise”. He humorously added that he took great delight in providing “incredibly skilled players, who possess instruments worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, with a $3 big tube” (Baver 2018). This embrace of unconventional, non-symphonic instruments perhaps signifies a deliberate departure from the symphonic sounds synonymous with Williams, while still paying homage to, and quoting, Williams’s compositions throughout the original score.

Ultimately, the utilization of pre-existing Star Wars music in Solo can be attributed to the thematic underpinning of destiny. Powell confirms this notion, suggesting that, as a composer, he had to make a choice about whether to approach the score within the context of the film or within the broader context of the franchise as a whole. He noted that as an audience, “[w]e know where [Han] is going, so there’s lots of games you can play with the audience” musically (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). The theme of destiny served as a framework that helped Powell reconcile having Williams on board. Once he acknowledged that Williams’s themes could be an integral part of the film, he saw the original cues as a kind of musical DNA from which he could build outward (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). Moreover, in the context of destiny, Powell made a conscious decision not to create any significant new music related to destiny, as he recognized that Williams’s original cues could effectively convey the characters’ future on screen. A notable example of this approach is evident in the first appearance of the Millennium Falcon. In this moment, a slowed-down, majestic orchestral and choral rendition of the main Star Wars theme provides an evocative, foreshadowing sonic link to the original films, explicitly indicating the ship’s destiny. As Powell remarked, at this stage in the chronological narrative, “there is no significance to that machine other than the destiny of it”, perfectly encapsulating the role of music in this sequence (The Resistance Broadcast 2021). Interestingly, the prequel trilogy, which precedes Solo chronologically, is only sparingly referenced in the film, with a solitary nod to “Duel of the Fates” occurring as Darth Maul appears in hologram form towards the film’s conclusion. Little else from outside the original trilogy is featured in terms of Williams’s cues.

When it came to original music, Powell ventured into uncharted territory, going beyond the use of vuvuzelas. For the exhilarating train scene and the arrival of Enfys Nest, a notorious marauder and pirate, he decided to employ a choir of Bulgarian women, describing their voices as “aggressive”. Powell’s rationale for this unconventional choice was that the choir produces a non-vibrato, “powerful female sound”, reminiscent of Williams’s choral scoring in The Phantom Menace. However, it also embodies fierceness and imparts a sense of trepidation to the audience, and consequently, to the protagonists under attack by Nest in the scene (Baver 2018).

Shortly after this sequence, Powell introduces what might be one of the most surreal track names in the Star Wars anthology: “Chicken in the Pot”. This is a diegetic song performed by a duet, one of whom—Luleo Primoc—is portrayed as a disembodied head in a jar. Powell, upon seeing early concept art, humorously likened this character’s visual appearance to a cooked chicken, which inspired the title of the cue. While the translation of the lyrics is still an ongoing process due to the Huttese language’s lack of a comprehensive, official lexicon, Lucasfilm employee Leland Chee confirmed that the song includes references to culinary words like hamburger, cucumber, Bolognese, and mayonnaise, along with mentions of hunger5. There has been some debate regarding whether the chorus holds connotations of hunger or potentially carries a sexual subtext, as one line alludes to someone being “good enough to eat” (Star Wars Music Minute 2022). However, Powell leans towards the more innocent interpretation, emphasizing the chicken-in-a-pot analogy or the visual similarity to create whimsical lyrics revolving around consuming various food items (Baver 2018). Initially, the song was in a language that Powell found online, but it had to be later translated into Huttese to align with intellectual property rights (The Resistance Broadcast 2021)6.

In summary, Solo: A Star Wars Story’s musical journey under John Powell’s direction is a testament to the depth and creativity that the Star Wars universe continued to inspire after Rogue One a few years earlier. The film’s use of Williams’s pre-existing themes and motifs, the integration of new leitmotifs and instrumental sounds, and the innovative diegetic placement of the “Imperial March” were all contributing to a new, rich and diverse musical landscape that would be continued in the Disney+ spin-off series in future years.

The Disney+ live-action series

The Mandalorian (2019– )

The Mandalorian, as the inaugural Star Wars television series exclusively available on the Disney+ streaming platform, signified a pivotal juncture in the convergence of the Star Wars franchise with the burgeoning realm of digital content distribution. Premiering in November 2019, this episodic venture helmed by creator Jon Favreau and executive producer Dave Filoni represented Disney’s ambitious foray into the realm of live-action serialised storytelling within the Star Wars universe. Set in the universe’s outer reaches, the series introduces audiences to the enigmatic and initially unnamed Mandalorian, a lone bounty hunter, as he navigates the lawless post-Empire galaxy in the aftermath of the fall of the Galactic Empire. The episodic narrative unfolds as a series of interconnected adventures, often reminiscent of the spaghetti western genre, as the Mandalorian takes on various bounties while seeking to fulfill a mysterious mission. This mission centres around the Mandalorian’s evolving relationship with “The Child”, colloquially known as “Baby Yoda” and later named Grogu, a Force-sensitive creature of great interest to both allies and adversaries. The episodic nature of the show also allows for a broader exploration of the Star Wars universe, delving into the lives of inhabitants beyond the core of the Skywalker saga. The Mandalorian adeptly pays further homage to the Western genre, drawing inspiration from classic films and television series while infusing them with a distinct Star Wars flair.

Ludwig Göransson, a highly acclaimed composer and multi-instrumentalist, undertook the pivotal role of composing the musical score for The Mandalorian. Known for his innovative approach to composition, Göransson brought his distinctive style to the show, enriching the storytelling experience with a fresh sonic dimension that could not be more dissimilar to the sound of Williams. His work on The Mandalorian marked an astonishing departure from the symphonic tradition associated with previous Star Wars instalments, but not without paying homage to Williams with some of the harmonic language used throughout. Like Powell and Giacchino, Göransson acknowledges the impact Williams had on the Star Wars universe, claiming “what John Williams created… was probably the best film music out there” (Grobar 2020). However, nowhere is Göransson’s departure from Williams’s symphonic style more evident than in the very opening sequence to the first episode.

The episode (and series) begins in a barren and windswept desert landscape on the remote planet of Arvala-7, setting the scene with visual aesthetics of desolation and isolation. The unfolding sequence is marked by silence, as the camera gradually reveals the distinctive helmet and armor-clad silhouette of the Mandalorian, who moves purposefully across the desolate terrain. There is a noticeable absence of dialogue and music. As the Mandalorian, whose name is later revealed as Din Djarin, enters a remote cantina, he is confronted by a group of unruly patrons, sparking a tense confrontation that hints at Djarin’s reputation as a formidable and skilled bounty hunter. The ensuing scuffle provides a glimpse into Djarin’s combat prowess. When he leaves the cantina, we finally hear the first rendition of Göransson’s opening ostinato (Figure 5).

Figure 5

The Mandalorian, the main theme ostinato performed on bass recorder (S1E01, 00:00:43) (personal transcription).

Göransson employs a bass recorder motif, bearing a resemblance to Ennio Morricone’s iconic spaghetti Western scores. This motif is designed to “evoke a quintessential Western whistle or the tension-filled musical theme of a cowboy standoff” (Eberl and Decker 2023). The motif itself is straightforward, featuring alternating two-tone notes that undergo modulation upon their return. This musical choice effectively captures the solitary existence of the show’s central character, conjuring vivid imagery and sounds reminiscent of the wild west. This is particularly evident in the opening scene of the season, where “Mando” trudges through a windswept desert.

In contrast to the traditional Star Wars cinematic formula, every episode of The Mandalorian opens without the customary introductory crawl. Nevertheless, it immediately establishes a distinctive atmosphere marked by a palpable sense of grittiness and authenticity. The absence of John Williams’s symphonic scores, which traditionally evoke the spirit of swashbuckling adventure reminiscent of the Golden Age of Hollywood, underscores the departure from the conventional tone of Star Wars feature films, continuing and building on the trend started in Rogue One and Solo. The bass recorder sound heralds a narrative departure, signalling The Mandalorian as a realm of storytelling that eschews the traditional family-friendly, action-adventure tropes, embracing a more mature and unflinching narrative approach.

The series distinguishes itself through its deliberate aesthetic choices, featuring dimly lit environments, weathered and dilapidated sets, and a cast of morally complex characters, encompassing both protagonists and antagonists. These visual and narrative elements converge to create an atmosphere that departs from the polished veneer typically associated with the Star Wars cinematic franchise, and that includes the symphonic sounds of Williams. Instead, it beckons viewers into a world that conveys a sense of realism and maturity, dwelling in the fringes and shadows of the overarching film narratives. This tonal shift invites audiences to explore a more nuanced and less idealised facet of the Star Wars universe, one where moral ambiguity thrives and where the dichotomy between light and dark becomes blurred, offering a narrative perspective distinct from the traditional cinematic storytelling. The indecisive, ponderous recorder sounds of Göransson that introduce us to the musical world of The Mandalorian reinforces all of this.

The Star Wars spin-off series, despite their limited or absent involvement of John Williams, periodically draw upon his symphonic musical legacy. Like Rogue One and Solo, this occurs through explicit utilisation of original leitmotifs from the film series or more subtly, via the employment of rich and Romantic orchestration reminiscent of Williams’s overarching compositional style within the nine films that he scored. In The Mandalorian, these instances are relatively sparse, but their impact is profound. For instance, in the climactic scene of the second season’s final episode, as Djarin bids a poignant farewell to Grogu while the digitally rendered likeness of Luke Skywalker whisks the young Force-sensitive being away for Jedi training, the evocative Williams Force theme naturally emerges. The music elegantly underscores Skywalker’s revelation, while in Djarin’s quiet yet emotionally charged act of removing his helmet to allow Grogu to witness his face, a more restrained emotional cue plays. This compositional choice subtly accentuates the nuanced essence of Grogu’s character and underscores the significance of this pivotal narrative moment within the context of the series.

In a stark departure from Göransson’s sparse, mysterious sound world for the series, a noteworthy musical transformation unfolds as Grogu embarks on his journey with Luke Skywalker. This moment can be characterized as a unique instance within The Mandalorian, evoking the expansive orchestral scoring of the late nineteenth century. Here, the orchestration takes on a richly romantic quality, featuring the inclusion of Wagnerian horns and swelling strings. Remarkably, this composition deftly incorporates The Mandalorian’s principal theme, adapting it to achieve a depth of emotion and sentimental resonance that aligns with Williams’s own neo-Romantic approach to scoring the galaxy. This singular instance serves as a testament to the series’ capacity to skilfully integrate and simultaneously evolve the musical identity of the Star Wars franchise.

The Book of Boba Fett (2021–2022)

The Book of Boba Fett follows the legendary bounty hunter Boba Fett and his trusted partner, Fennec Shand. The series, released in 2021 and 2022 on Disney+, takes place after the events of The Mandalorian and explores Fett’s journey as he steps into a new role as the crime lord of Tatooine’s underworld. After surviving the treacherous sands of the Sarlacc pit, Boba Fett sets his sights on the criminal enterprises that control Tatooine’s criminal underworld. With Fennec Shand by his side, Boba Fett aims to establish his authority and consolidate power in the lawless desert planet. The episodes delve into Boba Fett’s complex past, offering glimpses of his experiences and the events that have shaped him into the feared bounty hunter he has become. As he navigates the intricacies of Tatooine’s criminal organizations, he encounters various factions, adversaries, and allies, each with their own agendas and ambitions. Throughout the series, Boba Fett and Fennec Shand face numerous challenges, including rival crime syndicates, power struggles, and vendettas from their past.

The music to The Book of Boba Fett was composed by Joseph Shirley, with the main theme contributed by Ludwig Göransson on the back of his success with The Mandalorian. The Book of Boba Fett has a memorable main theme, incorporating prominent use of vocals and driving percussion. Göransson, of Swedish descent, has never admitted to having seen the film Ronia: The Robber’s Daughter (Ronja Rövardotter, Tage Danielsson, 1984), but the cue from that film entitled “Mattis & Borka-sången!” is extraordinarily similar to the main theme for The Book of Boba Fett, and it is improbable that direct inspiration was not taken from this film, coincidentally released in the year of his birth. Regardless of this anecdotal curiosity, the theme is certainly a departure from the Star Wars musical identity that Williams had created and nurtured in the nine Skywalker Saga films. The epigraph that opened this chapter, which is repeated here, suggests a degree of self-deprecation or anxiety around scoring Star Wars spinoffs. He claimed “[o]bviously, no one’s going to write music that is as great as what John Williams did.” (Grobar 2020) The outcome of this concern is that Göransson did not try to emulate or live up to Williams, but rather compose music that is unquestionably Star Wars, but more importantly unquestionably new. In The Mandalorian, the recorders formed the crux of the musical departure from Williams’s symphonic style, whereas in The Book of Boba Fett, it was his voice. Joseph Shirley, composer of the in-episode music, reinforced Göransson’s thoughts regarding following on from Williams in an interview podcast. The host of the podcast remarked that “[w]e all love John Williams, but it doesn’t sound like John Williams”, to which Shirley replied “[n]o-one can write like John Williams. John Williams writes like John Williams” (Score: The Podcast 2022).

Discussing the vocal main theme, Shirley explains that Göransson sat down with him and decided to use “a lot of vocals” to provide Fett’s character with a “tribal, primal, muscular, stoic, confident, strong” musical theme that reinforced his mythical status in the Star Wars universe (Score: The Podcast 2022). Through the use of nine baritone singers who provided the main theme’s wordless chorus but also grunts and chants elsewhere in the series, Shirley referenced Temuera Morrison’s Māori heritage as an inspiration point, describing the musical style as Tahitian or Polynesian; somewhat of an unintentional geographical misnomer, given Morrison’s New Zealand heritage (Score: The Podcast 2022). Furthermore, inspiration was taken from across the Tasman Sea, with didgeridoo sounds and “horn calls”, as well as “lots of styles of percussion” representing Fett throughout the series (Score: The Podcast 2022). The general consensus in the discussion with Shirley on the podcast is a set of new rules; new rules for what Star Wars sounds like. The host even remarked that many studio executives would have been scared away by the different sounds compared to Williams, but ultimately the music of the two composers is continuing to build up the brand and sound of the spin-off universe (Score: The Podcast 2022).

John Williams is not totally absent, though. The nods to Williams’s iconic Skywalker Saga scores within The Book of Boba Fett are infrequent but significant, with one such reference occurring as early as the midpoint of the first episode. As Boba Fett and Fennec Shand step into a bustling Mos Espa cantina, they encounter a familiar sight to fans of the Skywalker Saga: Max Rebo, a character from Jabba the Hutt’s palace in Return of the Jedi, performing music alongside a Bith character. The Biths were the original members of the Cantina Band featured in the original trilogy. This convergence of two diegetic musical elements is accentuated by their rendition of a remixed version of the “Cantina Band” theme from the original film series. This particular piece of music has transcended the Star Wars universe to become one of the most universally recognized musical cues throughout the entire Star Wars anthology.

Towards the conclusion of episode four, a noteworthy musical reference occurs, marking one of the first instances where the collective spin-off series begins to carve their own musical identity distinct from John Williams’s iconic compositions. During a conversation between Fennec and Fett about the impending war, Fennec suggests that Boba could acquire military support with money, asserting that “Credits can buy muscle, if you know where to look”. As this dialogue exchange wraps up, an unmistakable shift in the musical landscape takes place. Ludwig Göransson’s recorder takes centre stage, accompanied by the familiar bass ostinato that also forms part of The Mandalorian’s main theme. This musical shift seamlessly transitions into the main theme for Boba Fett, which underscores the final moments of the episode as the credits roll. This moment is noteworthy as it underscores the spin-off series’ ability to establish its own unique musical identity and canon, separate from the influence of John Williams. It signifies the series’ growing independence and creative evolution.

Obi-Wan Kenobi (2022)

Obi-Wan Kenobi, the highly anticipated six-episode mini-series released in 2022, marked the return of Ewan McGregor as the titular character, a role he hadn’t reprised on-screen since 2005, although he did make voice cameos in the sequel trilogy. The composition of the series’ score added an intriguing layer of complexity to the Star Wars musical anthology. Initially, British film composer Natalie Holt created an original theme for the show and the character of Obi-Wan. However, when John Williams joined the project, the dynamics shifted. Natalie Holt ceded control of the main theme, allowing Williams to take charge of the opening titles. Williams’s long-time collaborator, William Ross, also became part of the musical journey and contributed as a third composer, adapting Williams’s iconic Obi-Wan theme and incorporating other familiar film leitmotifs into the series. Despite Natalie Holt’s burgeoning back catalogue of successful music for screen, evident from her previous work, including Marvel’s Loki, she found herself as just one part of this particularly intricate Star Wars musical puzzle rather than the sole composer on the project. The division of composition duties remained somewhat ambiguous, and the arrival of John Williams, while undoubtedly welcomed by all, introduced a certain complexity to the series’ music, and perhaps prompted a level of anxiety felt by Powell during the Solo compositional process.

John Williams’s main theme subtly draws inspiration from the iconic Force theme while also bearing a striking resemblance to Siegfried’s leitmotif from Wagner’s Ring Cycle. In the hands of William Ross, who adapts Williams’s themes, the series adheres to the leitmotivic style that characterized the original films. These adaptations, though often subtle, manifest in variations in instrumentation or harmony, effectively conveying different facets of the characters. An exemplary illustration from the original film trilogy is the “Imperial March”, where the versatility of the orchestra is notably showcased during Darth Vader’s poignant aforementioned death scene. Here, the once menacing and sinister melody undergoes a transformative journey, passing through high strings, French horn, flute, and finally, the delicate notes of a harp. In Obi-Wan Kenobi, this same technique persists, albeit in a more nuanced manner. A noteworthy instance lies in a subtle tonal shift within Obi-Wan’s main theme. This shift towards a major tonality occurs as the lead character reveals a kinder and gentler side, symbolized, for instance, by his act of feeding a hungry animal on Tatooine. Figure 6 showcases the main theme, composed by Williams, with the kindness adaptation highlighted in Figure 7:

Figure 6

Obi-Wan Kenobi, main theme composed by John Williams (S01E01, 06:00) (Lehman 2023).

Figure 7

Obi-Wan Kenobi, “kindness” variation as Obi-Wan feeds a hungry animal on Tatooine (S01E01, 14:32) (personal transcription).

Obi-Wan Kenobi, as a series, tantalizes us with glimpses of John Williams’s musical style but only truly embraces it in the closing episodes. The Empire, and even the fearsome Darth Vader, march to the beat of an original score distinct from Williams’s iconic compositions. In a sequence where Vader unleashes terror upon a hapless village, indiscriminately taking lives, the initial tense soundscape, the haunting foregrounding of his ominous breathing, the strategic use of silence, and the chilling cries of the terrified villagers arguably paint him as a more formidable and menacing presence than even the renowned “Imperial March” could achieve. Nevertheless, it’s understandable how some critics may have found the score to be somewhat “generic” as Vader embarks on his merciless rampage (Zanobard 2022)7. Drawing upon Wagner not for the first time in this article, the sense of relief experienced when we finally hear some of Williams’s renowned leitmotifs is akin to the resolution of the Tristan chord after nearly four hours of Tristan und Isolde. The “Imperial March” makes its presence felt a bit earlier in the series, yet it’s when Obi-Wan bids farewell to Leia following a successful rescue mission that the magic truly happens. The melodies of Leia and the Force, composed by Williams, are heard briefly, with the original compositions of Holt or Ross seamlessly interwoven between them. The sheer number of reaction videos on YouTube featuring jubilant fans celebrating the emergence of these themes speaks volumes about their impact.

The critical reception of the score of Obi-Wan Kenobi is mixed. There is little to critique when viewed as a collection of individual musical cues. However, within the context of the series, critics believe it falls somewhat short, primarily due to what can be considered questionable decision-making. Unlike the other case studies in this article, Obi-Wan Kenobi is accused of being too much of a Williams “sound-a-like” compilation, without the stretching of the musical identity found in other spin-offs:

Throughout the score there were numerous scenes that screamed for a statement of the Imperial March, the Force theme, Princess Leia’s theme, or even a reprise of “Battle of the Heroes” from Revenge of the Sith. However, instead, Holt was made to essentially create ‘almost but not quite’ replicas of these iconic musical motifs, which robbed the show of some potentially powerful moments of emotional and dramatic catharsis, as well as removing much of the internal musical continuity and leitmotivic consistency. It’s just another bad decision among a series of bad decisions that left the show failing to live up to its potential, and it’s very surprising that John Williams may be somewhat to blame. (Broxton 2022)

Andor (2022– )

In 2022, the 12-part series Andor made its debut, serving as an origin story for the Rogue One rebel protagonist, Cassian Andor. Its release seemed understated, and the fanbase appeared intrigued, yet it lacked the typical frenzy associated with a Star Wars launch. What followed, however, was a classic case of under-promising and over-delivering. The series emerged as a revelation, despite its character ensemble mostly unfamiliar to casual Star Wars filmgoers, an absence of mentions of the Force, Jedi, or the Sith, and no cameo appearances from the A-List cast. Astonishingly, Andor consistently secured the top spot in ranking lists of Star Wars series, surpassing Obi-Wan Kenobi, The Mandalorian, and The Book of Boba Fett.

If The Mandalorian revealed a grittier, darker facet of the Star Wars universe, Andor cranked it up to the maximum. Across its 12 episodes, we witnessed the protagonist commit cold-blooded murder of a fellow rebel, another rebel protagonist off-screen murdering an entire Imperial family, including children. There was a former security officer desperately seeking attention and stalking a female Imperial supervisor, a senator trapped in a loveless marriage while deceiving her husband and essentially bartering her child into an arranged marriage, an entire prison floor subjected to electrocution, and the protagonist’s mother dying in solitude. This is the same Star Wars universe that introduced us to the likes of Jar Jar Binks, reinforcing how far removed the spin-off series are from the family-friendly narratives of the Skywalker Saga.

Within this rendition of the Star Wars universe, the classical musical style synonymous with John Williams may appear somewhat out of sync. It’s crucial to acknowledge Williams’s remarkable versatility as a composer—recall that he crafted both Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park in the same year. However, the unrelenting and harsh reality portrayed in this particular segment of the Star Wars galaxy doesn’t naturally harmonize with the neoclassical, Golden Age-inspired symphonic compositions that define his signature style.

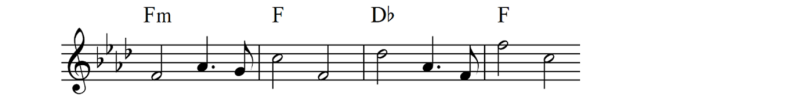

Opening title themes in film musicology are frequently overlooked, but Nicholas Britell introduces a captivating twist with Andor. Each opening theme shares a fundamental core, yet it undergoes a fascinating evolution, departing from its orchestral origins to mirror the upcoming episodes’ content. This approach stands in contrast to what Williams typically achieves in the films. In the Star Wars saga, consistency reigns supreme, as evidenced by the nine iconic opening crawls and their accompanying fanfare. While Williams masterfully wields the transformative potential of the leitmotif, Britell takes an innovative stride by incorporating the opening title theme into this compositional approach. The flexibility and fluidity of the opening credits foreshadowing the impending episode, this subtle yet impactful technique elevates the significance of the non-diegetic underscore, infusing it with purpose. In fact, one could argue that it imbues the score with more meaning than Williams’s opening fanfare, which, apart from serving as a leitmotif for Luke Skywalker, primarily accompanies the scrolling introductory text. Britell’s score is already providing hints about what is to unfold in the upcoming episode, with nuanced alterations that explicitly connect the main theme with the content of the forthcoming narrative.

There is a significant, pivotal diegetic musical moment in Andor. At Cassian’s mother Maarva’s funeral, a marching band assembles and delivers a poignant yet stirring funeral march. What makes this scene particularly intriguing is the fact that the instrumentalists on screen are genuinely playing their instruments, adding to the enjoyment as viewers try to discern the sci-fi modifications concealed beneath each instrument. This scene employs a time-honoured cinematic technique, the slow-building musical crescendo leading to a climactic event. Diegetic music possesses a hypnotic potency for heightening tension and suspense, especially when certain characters on screen hold knowledge that others do not. In the examples mentioned earlier, acts of violence were often at the centre of the crescendo, whether thwarted or realized. However, in the funeral sequence of Andor, the music culminates in a different form—a posthumous speech by Maarva, rallying the masses against the Empire8. These scenes represent a genuine departure from the utilization of diegetic music in the Star Wars feature-length films, where John Williams’s non-diegetic underscore typically propels the narrative. In Andor, music takes centre stage and is presented to us as a vital, living component of the Star Wars universe, contributing to raw realism and narrative development. It is worth noting that the somewhat unrefined and unpolished sound of the band contributes to the authenticity of the scene. The portrayal of instrumentalists who likely don’t rehearse together frequently, gathering to pay tribute to a beloved local resident, inevitably results in a somewhat rustic performance. This natural imperfection enhances the genuine mood of the moment.

Conclusion

Star Wars and John Williams is one of cinemas great partnerships, akin to Williams’s personal and professional relationship with director Steven Spielberg. They work so effectively and efficiently together, and it may be jarring to tear them apart. However, change can indeed be a positive force, even for the most dedicated fans of John Williams and the Star Wars universe. Personally, I found a deeper connection with The Mandalorian and Andor than with the three most recent Star Wars films, and I attribute this resonance largely to the music. Perhaps John Williams’s musical legacy is akin to a comforting security blanket that a child clings to for as long as possible. Yet, for growth to occur, one must eventually let go. To extend the analogy of children maturing, the introduction of composers like Natalie Holt, Nicholas Britell, John Powell, and Ludwig Göransson may symbolise Star Wars entering its transformative teenage years, characterized by experimentation, mood swings, and, upon reflection, a newfound appreciation for the evolution it has undergone. Film music is built on stereotypes, both stylistic and generic, and whilst Williams’s music will be the sound of Star Wars forever, this need only apply to the films for which he composed the music. It is limiting and unfair to suggest that the music that comes after Williams’s reign is inferior or need live up to Williams, and Williams himself, in his typically self-deprecatory and humble manner, would heartily agree. His music for the nine films is but one part of the Star Wars universe across a range of media, and we now enter a post-Williams age whereby stylistic homages and entirely new sounds can come to the fore and take the fictional universe in new directions sonically.

So, to quote Göransson one final time and to respectfully disagree with him, it is perhaps a fallacy to claim that “no-one’s going to write music as great as what John Williams did”. Greatness is subjective, whilst progress and evolution are essential, and the Star Wars galaxy far, far away no longer needs to rely on Williams’s music written a long time ago…