Writing at the turn of the century, Michael Cronin (2003) observes that translation has long been instrumentalized to support “the unchecked spread of market-ideologies, the global economic and political influence of transnational corporations, the emergence of international tourism, the dominance of Western scientific and technical paradigms, and the global spread of Western popular culture” (p. 72). The globalization of the economy, i.e., the swift and smooth flow of goods and finances across most countries, rests upon an equally swift and smooth flow of information. This Babelian dream has only recently been made possible. The invention of the web, the development of digital messaging, and now the advent of generative AI are all less than twenty-five years old.

Although the internet and various technologies of translation have helped to some extent to fulfil the “desire for mutual, instantaneous intelligibility between human beings speaking, writing and reading different languages” (Cronin, 2003, p. 59), they have had a number of serious drawbacks. English as a global lingua franca continues to dominate the internet and remains the pivot language in most language technologies, despite various initiatives that have sought to empower and extend the reach of other languages.1 The dominance of English and a small number of European languages whose global reach is a consequence of their colonial history continues to perpetuate linguistic imperialism and contributes to cultural homogenization and the persistence of inequalities in global communication. Online data inherits these linguistic, cultural, and epistemological asymmetries in a self-perpetuating spiral and exacerbates them by feeding them into translation machines (Mariani, 2012; Boéri, 2018).

Scholarly on- and offline knowledge production does not escape this self-perpetuating spiral, as research quality assessment is increasingly driven by metrics rather than the informed judgement of peers and the wider public, an issue outlined and critiqued in detail in the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA, 2012).2 Consumed by the race for a higher position in the global rankings, many higher education and research institutions uncritically rely on research metrics that devalue locally relevant research, particularly when it is produced in languages other than English. For instance, principle 3 of the Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics states that “The impact factor is calculated for journals indexed in the US-based and still mostly English-language Web of Science. These biases are particularly problematic in the social sciences and humanities, in which research is more regionally and nationally engaged. Many other fields have a national or regional dimension—for instance, HIV epidemiology in sub-Saharan Africa” (Hicks et al., 2015, p. 430). Reliance on “black-box evaluation machines”, as the Leiden Manifesto calls them, has nurtured an unhealthy culture of publish or perish and led to an explosion in the number of papers published in the last decade, in turn inflating journal impact factors (Hanson et al., 2024) and perpetuating their linguistic, cultural, and epistemic biases. This profit- and ranking-driven infrastructure is unsustainable and highly damaging, as “paper productivity” ultimately undercuts “scientific productivity” (Boulton & Koley, 2024). That is, data overrides knowledge to the point of saturation for the scientific community and the wider public alike. The exponential growth in the number of papers published in English is also a strain on non-English speaking scholars, who have to carry the logistical and financial burden of translation.

Given the scale of the problem and the pressure on academic labour, AI and machine translation may come across as a bargain: they can deliver large quantities of research data in multiple languages almost instantaneously, and at low cost compared to human labour. But this technological solutionism fails to question the research publishing infrastructure that created it and continues to support it. It also turns a blind eye to the multiple asymmetries in the way AI extracts, exploits and delivers data—and their ethical and physical ramifications.

The dominance of English in scientific publishing on- and offline continues to disadvantage speakers of other languages and “disproportionately benefits native or fluent English speakers”, as detailed in a recent editorial of Nature Human Behaviour (“Scientific publishing has a language problem”, 2023, p. 1019). Despite a number of genuine attempts on the part of various journals and editors to remedy this situation, including journals in the field of translation, the overall picture remains largely the same. The problem, as the Nature Human Behaviour editorial puts it, is that “piecemeal efforts are unlikely to solve systemic problems”, in part because “publishing a translation currently requires additional resources and editorial oversight, which means extra labour and costs”. To make things worse, moreover, “[a]s in other steps taken to foster inclusion, the costs are borne by members of the population they seek to include” (“Scientific publishing has a language problem”, 2023, p. 1019).3 Encounters in Translation attempts to overcome some of these problems more systematically, through long-term and sustainable solutions rather than erratically and piecemeal.

The AI (translation) bargain: What lies behind the rhetoric of equity

One challenge that Encounters seeks to address is that the value attributed to the immediacy of transactions has gradually cast translation as an expensive source of delays in the production chain (Cronin, 2003, p. 60). AI-powered automated translation and content generation appear to solve the problem, with many chatbots offering instant, free, and multilingual solutions. In July 2024 alone, Google Translate added support for a further 110 languages, a quarter of which were African languages and five of which were languages from the Philippines (Barreiro, 2024). On the face of it, automated translation of scientific content appears to offer a perfect solution to the problem of language access. The editors of Nature Human Behaviour are “optimistic that AI-powered translation has the potential to create more equitable access to science” (“Scientific publishing has a language problem”, 2023, p. 1019) and are actively exploring the possibility of using this technology to generate translations of their journal articles.

Behind the rhetoric of equity and diversity and the attendant freemium interfaces presented to the public and the scientific community, however, lies an unethical and extractive model of translation and authorship that has unprecedented environmental, labour, and cultural costs. The high-speed processing of large quantities of data is an energy and water guzzler (Dhar, 2020; Ren, 2023). A recent Goldman Sachs report (2024) predicts that as the “AI revolution gathers steam […] data center power demand will grow 160% by 2030” and “carbon dioxide emissions of data centers may more than double between 2022 and 2030”. Importantly, these consumption and pollution levels are not equally distributed across the globe, and not even within Europe, meaning that the Global North exports its digital waste to the Global South, exposing the latter’s populations to serious health and climate threats. The power demands of a small number of North European countries attempting to cope with the AI revolution are expected to rise by 50-60% by 2033, and their power needs “will match the total current consumption of Portugal, Greece, and the Netherlands combined” (Goldman Sachs, 2024).

Increased reliance on generative AI further demands the recruitment of a precarious workforce— mostly people of colour, and mostly located in the Global South—to service the new system under difficult conditions (Rowe, 2023). Kwet’s (2024) detailed account of the downside of the global digital economy unveils a modern-day slavery system where data workers annotate reams of data, train artificial intelligence models, clean social media networks of their disturbing content for American Big Techs, and extract rare metals in Chinese-owned supply chains. The processing of reams of data, including “visual data obtained from surveillance drones and satellite imagery”, into “actionable intelligence” further serves to improve predictive power for the police and military and enhance “warfighting speed and lethality” (Kwet, 2024, p. 157). To halt the gender, racial, class, environmental, and military violence of the colonial and capitalist tech economy, Kwet proposes digital degrowth as a paradigm that can harness the social and climate justice struggles of our time and reconfigure tech politics.

AI training practices are also secretive and fundamentally non-consensual (Reisner, 2023). AI and machine-(aided) translation technologies appropriate the work of human translators without crediting or remunerating them. In a typical and now widespread practice, for instance, Microsoft’s Swahili translation tool, launched in 2015 and integrated into various commercial products since, relied for its development on the work of unpaid, volunteer translators recruited by Translators Without Borders (Piróth & Baker, 2021, p. 417).

AI training practices do not just appropriate the work of translators, they also appropriate and devalue the work of authors. The Atlantic revealed in September 2023 that 183,000 ebooks had been used by Meta to train LLaMA, their generative AI system. This was done without the knowledge or consent of authors (Reisner, 2023). In a recent development that shocked many in the scholarly community, Informa (the parent company of Taylor & Francis) sold access to all Routledge books to Microsoft to train their AI systems. They did so without the knowledge or consent of authors, and without offering authors any remuneration, despite Informa earning £8 million from the deal in the first year alone, followed by recurrent payments of unspecified amounts in the following three years (Potter, 2024). The Bookseller further revealed on 25 July 2024 that the company was set to sign a second deal worth £58 ($75) million. Rather than use the additional revenue to raise wages or royalties, or pay for some of the unremunerated labour that allows the publishing industry to function (editors, reviewers, etc.), the company intends to “reinvest a third of its AI-related profit into ‘accelerated technology, open research and AI product development’” (Battersby, 2024) that will no doubt further entrench and normalize the practice of relying on a precarious and under-remunerated workforce in the publishing industry.

Translation is firmly embedded in this extractivist digital economy (Kenny, 2017, p. 13). There is a need to refocus on the craft and the labour of translation, but digital degrowth should not be taken to mean a humanist return to a pre-tech utopian past. Digital degrowth can reconfigure translators’ relationship to the machine (Cronin, 2020; Moorkens & Rocchi, 2021; Talbot, 2022) and reconceptualize data as a common good (Moorkens & Lewis, 2019). Against the growing, unquestioning faith in AI-powered automated translation in scientific circles, it can challenge the emphasis on extensive and humanly unchecked dissemination of research results across languages by promoting critical reflection on the cultural, epistemological, and political complexities of knowledge mediation and circulation, without which there can be no sustainability.

Encounters in translation: Promoting humane translation and knowledge production

In an attempt to contribute to a richer and more humane alternative in scholarly communication, Encounters adopts a model of collaborative, multilingual, community-based translation. Our long-term objective is to produce a fully bilingual English-French journal, including all content on the site, using primarily human translators. This is a compromise dictated by the sources of support currently available to the journal, and our own linguistic skills, rather than a deliberate policy of promoting English and French as scholarly lingua francas. At the same time, and as an important step in the direction of creating a more multilingual publishing environment, Encounters has committed to producing ‘short formats’ (titles, keywords, short abstracts, and 1000-word synopses of all articles) in as many languages as possible. At the moment, this endeavour is dependent on the availability of volunteer, mostly unpaid translators, the majority of whom are graduate students of translation and interpreting in a variety of institutions and geographical locations. A Memorandum of Understanding with the Edwin C. Gentzler Translation Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst covers the cost of some paid freelance translators employed by the Center; these paid translators provide a limited number of translations for Encounters. Authors may also draw on their own resources to commission translations of their papers or synopses.

This is in no way an attempt to exploit or devalue the labour of translators. All translators are credited, and the journal editors themselves are not remunerated financially. Likewise, the platform hosting the journal, Prairial, reaps no financial benefit from this publication. No one in this project benefits financially,4 although we acknowledge that editing a journal, like publishing a journal article, does offer some indirect rewards for academics. Naming and crediting translators of all abstracts and synopses is a way of ensuring that some of these indirect rewards are also enjoyed by them. Last but not least, translated content is treated as an academic production in its own right, with every translated paper and synopsis assigned a DOI, meaning that translator details are registered in the metadata, and that their work for Encounters can be included in and enhance their academic portfolio.

Languages covered so far have included Arabic, Bengali, Catalan, Chinese, Flemish, German, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Malagasy, Mapudungun, Norwegian, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Quechua, Spanish, Tajiki, and Turkish—in addition to French and English. The long synopses are designed to provide a sufficiently robust understanding of the main argument to allow readers to decide whether they wish to contribute to the journal’s language coverage by volunteering a full translation of the article into their respective languages. They are also important for enhancing the visibility of authors, whose work can become better known and sufficiently accessible for other scholarly communities to engage with. Finally, expanding beyond the usual languages of scientific communication and translation contributes to language equity and justice without which science cannot benefit society as a whole. Since all articles are published in open access format, readers are free to translate them in full and publish them in other venues, subject to the restrictions of the CC BY-SA 4.0 licence (specifically that any reproduction or remix must credit the journal and author). We encourage colleagues in various parts of the world to make use of the open access content of the site in this manner and are open to making translations of full articles (and/or additional translations of synopses) available on the Encounters site.5

This alternative relies on a specific open access model, called Diamond open access. Unlike Gold open access, which requires the payment of often prohibitive Article Processing Charges (APCs) that are beyond the means of colleagues with limited institutional or personal financial resources, Diamond open access is not only free for readers but also for authors. Its economic model depends on institutional support (financial or otherwise). In the case of Encounters, the support is provided predominantly by research centres and universities that are duly credited on the journal website, and by Prairial, a pépinière de revues (journal incubator) located at the University of Lyon (France), which provides editorial, legal, and technological support free of charge. Strongly committed to a humane academic publishing ecosystem, and supported by a large institutional public network that promotes open science,6 Prairial professionals use state-of-the-art technologies and know-how to make open access publishing a sustainable and rigorous alternative to the publishing oligopolies.

Translation in the open science movement

The increased reliance on extensive and humanly unchecked dissemination of data, and the commodified and individualized relation to knowledge that characterize the current era are both at odds with the spirit and ethos of science, and especially the open science movement. Scarcely studied by philosophers and historians of science (David, 2004), the open science movement is mostly advocated by public institutions—at national, regional, and international levels. Examples of these public institutions include the CNRS (French National Centre for Scientific Research), the European Union, and the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).7

Conceived as a transnational, transdisciplinary, and critical framework, the open science movement seeks to harness the potential of open information technology tools to break down the barriers that hinder fair and equitable production, dissemination, and access to knowledge. As defined by the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science (2021), open science is

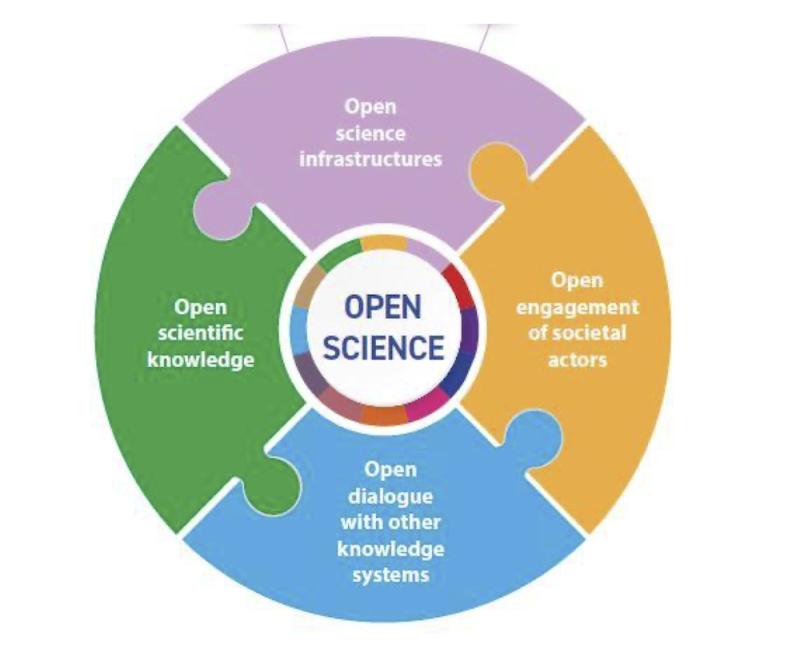

an inclusive construct that combines various movements and practices aiming to make multilingual scientific knowledge openly available, accessible and reusable for everyone, to increase scientific collaborations and sharing of information for the benefits of science and society, and to open the processes of scientific knowledge creation, evaluation and communication to societal actors beyond the traditional scientific community. It comprises all scientific disciplines and aspects of scholarly practices, including basic and applied sciences, natural and social sciences and the humanities, and it builds on the following key pillars: open scientific knowledge, open science infrastructures, science communication, open engagement of societal actors and open dialogue with other knowledge systems. (p. 7)

In making explicit reference to “multilingual scientific knowledge” and “open dialogue with other knowledge systems”, this first attempt to provide an international definition of open science clearly signals that languages, cultures, and epistemologies are the cornerstones of an inclusive scientific ecosystem, sustained and transformed by multiple players positioned in and outside academia, and across disciplines and fields of practice. A brief review of some of the key pillars of open science listed in the definition above highlights the practical and theoretical significance of translation in the open science movement.

Being contemporary to the development of artificial intelligence, open science has elaborated a critical approach to technological “open science infrastructures” which requires adhering to two sets of principles: FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) and CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics). These principles require open science infrastructures to be public, internationally interconnected and interoperable, free, and non-commercial. They must support societal relevance, knowledge preservation, access, reuse, and control by the community. Within this framework, the UNESCO (2021) recommendations make explicit reference to the “potential risks and ethical issues that may arise from the development and use of those tools using artificial intelligence technologies”, while acknowledging that the process of generating and sharing knowledge can be boosted by information technology tools that “automate the process of searching and analysing linked publications and data” (p. 25). There are therefore “technical requirements specific to every digital object of significance for science, whether a datum, a dataset, metadata, code or publication”.

The UNESCO recommendations recognize knowledge holders and producers as rights holders within open infrastructures and stress the need to “promote the inclusion of knowledge from traditionally marginalized scholars” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 15). Open access to all knowledge, produced and shared within the framework of CARE and FAIR principles, is the defining feature of the idea of “open scientific knowledge” (p 9). The recommendations therefore require all knowledge to be

available in the public domain or under copyright and licensed under an open licence that allows access, re-use, repurpose, adaptation and distribution under specific conditions, provided to all actors immediately or as quickly as possible regardless of location, nationality, race, age, gender, income, socio-economic circumstances, career stage, discipline, language, religion, disability, ethnicity or migratory status or any other grounds, and free of charge. (UNESCO, 2021, p. 9)

Intersectional access to knowledge as a product goes hand in hand with a participatory process of knowledge production, in the form of open research methodologies and evaluation processes. The recommendations emphasize the importance of “open engagement of societal actors”, including scholars, civil society, public institutions, and state and inter-state actors whose collaboration and critical engagement with knowledge production and circulation are a cornerstone of open science (UNESCO, 2021, p. 13–14).

The open science movement thus strives for sustainability and equity in the production, sharing, and dissemination of knowledge. Collaboration requires scientific knowledge to circulate across disciplines, spaces of decision making, and among the public at large, and this cannot be achieved without various processes of mediation. Given the geographic, linguistic, and cultural situatedness of knowledge, one would expect translation to be central to this endeavour. Surprisingly, however, the UNESCO recommendations identify key scientific sites of mediation, including “scientific journalism and media, popularization of science, open lectures and various social media communications” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 27), but make no mention of scientific translation. This is at odds with the practical and theoretical significance of translation for the linguistic, cultural, and epistemological inclusiveness that open science seeks to develop on the basis of its four main pillars (Figure 1):

Figure 1: The four pillars of open science, adapted from UNESCO (2021, p. 13)

The lack of engagement with translation in the UNESCO recommendations is certainly not new in the ecosystem of science. Indeed, human translation has received little support in the area of research and academic publishing, despite several alarm bells being sounded in relatively recent years. In France alone, these include the report État des lieux d’une urgence :circulation des idées en Europe (Taking stock of an emergency: circulation of ideas in Europe), produced in 2009 by scholars, publishers, and readers in the humanities and social sciences. The report highlights and critiques the compartmentalization of knowledge in these areas. The Manifeste pour une édition en sciences humaines réellement européenne (For truly Europe-wide publications in the humanities manifesto, 2009) that emerged in its wake explicitly calls for supporting translation in the academic publishing industry.

Consequently, independent scholars and editors have continued to develop small-scale initiatives to translate academic knowledge for wider dissemination, relying on limited public resources and/or volunteer labour. This is evident in the translation efforts of several journals hosted by OpenEdition, an open access digital publishing infrastructure in the humanities and social sciences which collaborates with Prairial. Hosting some 600 journals across different countries and disciplines, the infrastructure of OpenEdition does not include translation, but many of the journals it hosts individually endeavour to include translations of at least some of their content. Translation is generally undertaken on a volunteer basis (as in the journal Tracés; see Calafat & Monnet, 2015). However, some journals have succeeded in raising funds to recruit translators: a case in point is Symbolic Goods, which delivers fully bilingual English and French content. These public- and volunteer-supported translation efforts may well be more pervasive in various parts of the world than we are currently aware of, but they remain relatively invisible, limited in scope, and slow to spread as practices, compared to the fast-changing, increasingly AI-dependent landscape of the scientific publishing world.

It is only recently, and in the wake of the Helsinki Initiative on Multilingualism in Scholarly Communication (Helsinki Initiative, 2019) to support international and locally relevant research in multiple languages, that the question of embedding translation in open access scientific publishing infrastructures was placed on the open science agenda. Of particular interest is “Translations and Open Science”, funded by the French National Fund for Open Science (FNSO) and led by OPERAS, a European research institution which aims to develop a sustainable research infrastructure, specifically for the Humanities and Social Sciences. The Translations and Open Science project envisions the creation of a “demonstrator” (prototype) to prefigure a large-scale process of multilingual and collaborative translation on a dedicated platform (Fiorini et al., 2020). Relying on using machine- and computer-assisted translation to produce multilingual translations of scientific content in all languages, the project was envisioned around three main phases: (a) compiling discipline-specific parallel corpora to extract terminology; (2) testing/evaluating the output of machine translation engines; and finally, (3) integrating translation technologies, translation workflows and guides into a dedicated platform for collaborative use by all players in the publishing ecosystem: editors, publishers, platforms, authors, translators, readers, etc.

This ambitious project is in line with various other large-scale, open source, interoperable, and publicly funded initiatives—OpenEdition and Prairial being good examples—that have yielded excellent tools and spaces for the research community to extricate itself from profit-driven and Anglocentric publishing infrastructures. However, language processing and engine training may run counter to the ideals of sustainability embraced by the Translation and Open Science Project, and the UNESCO recommendations more broadly. One of the four exploratory studies to lay the foundations of the translation service raises this issue (study number 1, in Fiorini, 2023). It alerts us to the consequences of relying on machine translation, which is “quite demanding in terms of energy and invisibilised human work” and “can perpetuate linguistic and cognitive biases and lead to a loss of human skills” (Fiorini, 2023 ; see also Auffret et al., 2024 for the full report on study 1, available in French). Mapping translation needs, practices, and tools in the context of scholarly communication, the study further underlined a lack of systematicity. For instance, in the humanities and social sciences, where particular emphasis is placed on style to convey meaning, the resort to computer-assisted translation—and particularly to machine translation—is seen as less desirable, compared to the hard sciences. Given such a fragmented landscape, the authors of study 1 argue that the needs of the community (publishers, translators, authors, stakeholders) can be catered for by developing ad hoc collaborative tools, rather than a large-scale optimization model, and that a flexible, modular, and interoperable design may be more productive than a one-size-fits-all platform.

Translations and Open Science remains the most advanced and large-scale initiative to embed a collaborative translation design in scholarly production (Leão et al., 2023), particularly in the humanities and social sciences, the core of OPERAS’ remit. The difficult and pressing question of humane translation and editing in this ecosystem is still to be addressed, however: there is an urgent need to create a translational space that positions technologies at the service (rather than in control) of the process of meaning mediation across linguistic and epistemological asymmetries.

This brings us to a key question: why does ‘humane translation’ matter in science? We argue that science is a practice performed in constant dialogue with a community of peers and the public, which cannot be reduced to a mere interlinguistic transfer of content and data.

Data is indeed essential to identifying patterns, and the digitization of scientific material has enabled considerable progress in various areas. AI technologies promise to help us achieve even more progress in various areas of human activity. One expects a number of breakthroughs in protein synthesis, for example, or aeroplane maintenance. But, similar to its limitations in dealing with languages, AI only tackles one aspect of reality in these scenarios: the one amenable to statistical probability analysis and couched in standard, repeated patterns of expression. But this type of modelling is only one aspect of science, which is fundamentally a process of discovery that is deeply marked by uncertainty and subject to continuous renegotiation rather than a collection of facts that can be documented and recycled (Latour, 1988; Stengers, 2000). Examining loopholes and failures of all sorts is often fruitful, and these tend to be overlooked by AI-powered data collection. Scientific research also thrives on harnessing diverse points of view, on thinking outside the box. It is not a disembodied individual endeavour but is rather rooted in our bodies and our interactions, even our emotions (Damasio, 1994).

Any assessment of the contribution of AI to enhancing scientific knowledge must also examine the risks inherent to academic publishing. Research has an impact on society: it informs public policies, it may be used as evidence in heated debates with serious consequences, and is of course routinely appealed to in court.8 Relying on fully automated translation or generation of abstracts and other scientific output can therefore have a far reaching, negative impact on various areas of social and political life.

Given that various communities as well as public institutions are increasingly investing resources in the development of translation in open science, we see translation as a new paradigm in transdisciplinary and translational endeavours to engage with, mediate, and integrate knowledge that has been compartmentalized in disciplinary and societal silos, and scattered across the linguistic centres and peripheries of the ecosystem of knowledge. Within this paradigm, Encounters seeks to create a space where scholars with the requisite expertise in the field can contribute actively to the debate on the politics and practice of translation in the context of knowledge production and circulation, irrespective of their race, ethnicity, religion, physical location, gender, sexuality, or migratory status, as advocated by the UNESCO recommendations. This demands a more critical gaze on both transdisciplinarity and translation studies.

Transdisciplinarity and translation studies

Because Encounters in translation emerged within the public ecosystem of open science to function as a critical, transdisciplinary forum on translation, it is important to begin by reflecting on the two main elements in the journal’s remit: the potential of translation as both an object of enquiry and a practice, one that can leverage open and transdisciplinary science to harness the cultural, linguistic, and epistemic richness of the world in which we live, and the concept of transdisciplinarity, including its relationship to the more widely used ‘interdisciplinarity’. Ultimately, the aim is to provide a forum for debating the construction and circulation of translational knowledge in the academic sphere, the compartmentalization of knowledge in academic and disciplinary silos, the corporate structures that support these processes, and the ramifications of AI-powered automated translation as the way forward in the twenty-first century publishing industry.

Translation is an emerging paradigm in the open science and open access movements. It has the potential to counter the uncritical use of machine- and AI-generated content, with its linguistic, cultural, and epistemological ramifications. Approaching transdisciplinarity and open science from the perspective of translation can make a substantial contribution to the cultural sustainability of academic publishing and, more broadly, of science and societies.

To begin with, it is necessary to distinguish interdisciplinary reciprocity in translation studies from what we refer to as translational transdisciplinarity. The former focuses on how much the field has imported from other disciplines compared to what it has managed to export (Zwischenberger, 2019; Bednárová-Gibová, 2021), whereas the latter involves exploring the translational relations that underpin ecosystems of knowledge, including not only the humanities and social sciences but also the technical, life, and natural sciences. Encounters seeks to elaborate a position beyond the confines of a single discipline in order to examine the politics and practice of translation in the broader ecosystem of academic research and publishing, and their societal ramifications. Translation not only underpins but is also shaped by the cross-fertilization between fields of knowledge, as well as the epistemological traditions and the political aspirations that constitute various ecosystems of knowledge.

The field of interdisciplinarity studies, which emerged in the 1970s, distinguishes multidisciplinarity from interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. In a seminal gathering in Paris in 1972, under the auspices of the CERI (Centre for Educational Research and Innovation) and the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), scholars from various institutions provided a roadmap for universities to steer research and education towards addressing the societal challenges of the time (Apostel et al., 1972). Advocating for a holistic approach to knowledge, and for teaching disciplines “in the context of their dynamic relationship with other disciplines and in terms of societal problems” (p. i), they broadly defined interdisciplinarity in the abstract of the resulting volume as “the integration of concepts and methods between disciplines in teaching and research” (p. i). They further established three stages in the process: multidisciplinarity (the juxtaposition of knowledge arising from various disciplines while remaining within the boundaries of a given discipline), interdisciplinarity (the integration of knowledge from different disciplines into a coherent whole), and transdisciplinarity (transcending the traditional boundaries of disciplines, including the boundaries between the natural, social, health sciences and humanities). While these concepts and definitions have been much debated over the years (Klein, 1990; Stember, 1991; Choi & Pak, 2006), they have remained relatively stable.

What is of interest for our purposes and for positioning translation in relation to today’s scientific and societal challenges is the vision of science that lies beneath these normative claims on inter- and trans-disciplinarity. Since the inception of interdisciplinarity studies, going beyond individual disciplines has been conceived as a response to the need to restructure the overall system of Society, Science, and Nature in order to ensure the renewal of education and research to innovate for and with a constantly evolving society (Apostel et al., 1972). This process, however, may be underpinned by different epistemological premises and aims across schools of thought. For instance, transdisciplinarity, which has received more attention than interdisciplinarity since the turn of the century (Klein, 2013), may pursue a neopositivist conception of knowledge:

As the prefix ‘trans’ indicates, transdisciplinarity concerns that which is at once between the disciplines, across the different disciplines, and beyond all discipline [sic]. Its goal is the understanding of the present world, of which one of the imperatives is the unity of knowledge. (Nicolescu, 2018, p. 74)

Alternatively, transdisciplinarity can be conceived as “an umbrella term for all kinds of efforts towards reflexive co-evolution of science, technology and society” and as a methodology that “creates interfaces between science and society to address challenges, by generating knowledge and solutions for unstructured problems” (Regeer & Bunders, 2009, p. 42). Here, knowledge production and innovation are contingent upon a spatially and temporally situated problem, thus making the unity of knowledge (insofar as it is achievable) a means rather than an end in itself.

The attempt to move beyond disciplines, as suggested by the prefix “trans”, cannot take place in a vacuum but is situated within specific research traditions. For example, one may go beyond disciplines through a traditional mode of academic knowledge production, generally departing from homogeneous, single-discipline lines to achieve theoretical, conceptual and/or empirical goals. Alternatively, one may adopt a context-based approach by addressing a complex problem which cuts across disciplinary boundaries in order to create knowledge for a specific purpose. The latter has become more popular since the turn of the century in interdisciplinary studies, as attested by the new label for this field of enquiry, namely “integration and implementation studies (I2S)”, which now coexists with “interdisciplinarity studies” and “transdisciplinarity studies” (Lyall et al., 2011, p. 178–179).

What is strikingly missing from these developments is a reflection on language, race, gender, and culture, a dearth which demonstrates the continued marginalization of critical theories elaborated in the humanities and social sciences. If open science is to develop a sustainable and equitable ecosystem of science for addressing the challenges of our constantly evolving society, it needs to adopt a more critical approach to transdisciplinarity. An interesting contribution in this regard, and particularly relevant to Encounters, is Frédéric Darbellay’s (2015) article in Futures. Stressing that interdisciplinarity is an oxymoron, he argues and empirically demonstrates that there is a tension between the discourse of interdisciplinarity on the “decompartmentalization of disciplines” (Darbellay, 2015, p. 164), adopted across the board, and actual research practice, where disciplinary routines remain intact, thus leading to a “neutralization” of the transformative capacity of interdisciplinarity (Darbellay, 2015, p. 167). More importantly, Darbellay (2015) acknowledges the visions of transdisciplinarity discussed earlier—namely, transcending boundaries via a reconfiguration of “disciplinary divisions within a systemic, global and integrated perspective”, or a “more pragmatic, participative and applied” orientation to transdisciplinarity that “can be thought of as a method of research that brings political, social and economic actors, as well as ordinary citizens, into the research process itself, in a ‘problem-solving’ perspective” (p. 166). But he adds a complementary orientation which may constitute a meta-level of critical analysis and reflection: “transdisciplinarity applies also to the exploration of the complex relations woven in a dialogue between the scientific cultures deriving from the technical sciences, life and natural sciences, and the human and social sciences” (p. 166).

Because knowledge is linguistically, culturally, and epistemologically situated, we consider these complex relations as translational in nature. It is timely and necessary, we argue, to explore the complex translational relations that make up our dynamic ecosystems of knowledge. Translation theory and practice, however, are not neutral tools. Accounting for, mediating and integrating various epistemological traditions and political aspirations demands a critical approach to both. Equitable and sustainable ecosystems of knowledge require participation and deliberation across as well as within disciplines. Translation studies has a key role to play in contributing to a transdisciplinary ecosystem of knowledge. But like transdisciplinarity, it needs to harness the critical theories developed in the humanities and social sciences and to widen the debate to include scholars and practitioners from across the world.

Like other disciplines, translation studies must begin by directing its critical gaze at its own modes of thinking and its location within the wider research landscape and the world at large. The discipline has “long situated itself within structures of authority” by attempting to account for the role of translation in society “largely from the point of view of dominant groups and constituencies” (M. Baker, 2009, p. 222). Its priorities and discourses continue to privilege this location to a large extent, perpetuating various blind spots and prejudices that have increasingly been noted by scholars such as Kotze (2021), Bush (2022), Price (2023), and Tachtiris (2024), among others. It has further invested in elaborating a foundational narrative which locates its own origins in ‘the West’; Baer (2020) dissects this narrative and refers to it as “the originary myth of translation studies” (p. 221). ‘The West’, as many scholars have pointed out, does not primarily or exclusively refer to a geographical location. It is “demonstrably an imaginary entity, but the demonstration as such does not lessen its appeal or power” (Chakrabarty, 2008, p. 43). Although traditionally associated with the colonial history of European countries and US imperialism, the West now exceeds these spaces and perpetuates colonial and discriminatory structures within as well as beyond them. It has instituted and entrenched a ”Western gaze” on a global scale, ensuring that knowledge produced outside this imaginary zone, including knowledge produced by scholars located in the Global South, “is localized […] or associated with irrationality, unscientific methods and underdevelopment […] in comparison to ‘universal’ Western concepts, cases and knowledge” (Sondarjee, 2023, p. 691). This Western gaze continues to devalue racialized subjects and support a global dynamics of race that perpetuates the legacy of European imperialism.9 It is entrenched in academia and beyond through a “web of power relations that are part of colonialism’s power/knowledge construct” (Shwaikh, 2020, p. 130), which is further exacerbated by the digital economy, but has largely been ignored or downplayed by scholars of translation.

Like the powerful concept of citizenship, race is “an invented political grouping […] a political category that has been disguised as a biological one” (Roberts, 2011, p. 4), and is now recognized in fields such as international relations as a “central organizing feature of world politics” (Sondarjee, 2023, p. 690). Translation plays a major role in negotiating the way race and its intersection with language, gender, culture, and epistemes is understood, downplayed, suppressed, or mediated globally. And yet, as Tachtiris (2024, p. 122) points out, there is little or no engagement in the various disciplines that make up critical race studies with the role played by translation in mediating “how knowledge about race is produced and how race itself is produced” as a category through these processes of mediation. At best, translation is treated in this body of literature as a trope, or metaphor, rather than a complex interlingual process that shapes the very norms by which knowledge is produced, circulated and (de)valued. At the same time, racialized and other marginalized and disenfranchised subjects continue to be given scant attention in translation research, and in actual translation practice. As Inghilleri (2020) rightly points out, now that we have come to recognize the role that translation has played historically, and continues to play today, in perpetuating inequality and suppressing the voices of the oppressed, it is “incumbent upon us to initiate and validate translation practices that have as their aim to counter the systems of containment and control that are applied to marginalized voices” (p. 98). These practices must also include creating infrastructures and modes of research and writing that enable traditionally marginalized scholars to speak in their own voice, to be heard, and to “have a seat at the table” (Kotze, 2021). And they must create spaces within which humane translation, as advocated by Encounters, can “define a territory of difference that is dialogical and plural” (Vásquez, 2011, p. 28).

These arguments are highly relevant to Encounters as it seeks to open up spaces for equitable and ethically responsible reflection on translation within various ecosystems of knowledge and society at large. We do not see this goal as being served by simply ensuring a certain level of diversity in the editorial board, or in the range of authors and topics of articles published by the journal. Instead of such tokenistic gestures, we aim to effect actual change at the institutional and infrastructural level, rather than simply a change of rhetoric, and to transform the landscape of research on translation in a way that allows scholars of different backgrounds—including disciplinary backgrounds—to contribute equally to the debate. Approaching the labour of writing, reviewing, publishing, reading, and translating through a political commitment to open science, but also to care, equity, and sustainability, is the alternative we are building to resist the compartmentalization of knowledge in academic and disciplinary silos, the corporate structures that support this process, the marginalization of scholars of colour and colleagues located in the Global South and in “the internal South of the North”, and AI-powered fully automated translation as the way forward in the twenty-first century academic publishing industry. We invite all scholars interested in the study and practice of translation and their role in knowledge production and construction to join us in this endeavour.