My thanks to Guo Renju, who contributed to the Tibetan language research for this article. The abridged abstract in romanised Naxi pinyin was provided by He Ting and He Dongmei, with some minor editing from the author.

Beginnings

To risk the broadest understanding of translation means, perhaps, to also risk how we understand literature. This is because literature is inherently an act of translation, occurring both within individual texts and across the borders of national literary traditions. How, exactly, is literature translation? An answer would presumably involve investigating literary beginnings, how a literature comes into being. A review of the literature, however, reveals that translation, at least in much translation studies (TS) discourse, seems connected ontologically to literature primarily only in that oft-neglected category of world literature.

Wang Ning (2010) writes that translation makes world literature possible by allowing for circulation in international discourse, that, in short, translation allows literature to access the “world” of “world literature”. Chaudhuri (2012) offers a repetition of this refrain, saying “Translation plays an important role in creating the category of ‘world literature’”. Others have gone further: “the indispensable instrument of World Literature is translation” (Guérard, 2012, p. 63). Indeed, to understand world literature, we must understand translation, for as Bassnett (2016) says, “We cannot conceive of

World Literature without translation” (p. 312). Nothing reaches the world, or branches out across the global polysystem of languages, without being translated. But surely this is a given, for is that not the point of translation, at least as most would define it? I would argue that such TS discourse, despite its clear attempt to ‘embiggen’ translation, still ends up as a kind of marginalisation, or even a denigration. It is relegated to being a facilitator (indispensable or not) of whatever we claim as “world literature”, itself an inherently problematic and marginalised category.

It is possible to go one step further, as Jorge Portilla (2019) has done, and try to incorporate translation more ontologically into the literary process: “translation is not just the mere transposition of a text into another language, but it is rather an operation incorporated in the process of creation, especially in contemporary novels by Murakami and Bolaño” (p. 119). The writing of a contemporary novel is a translational act because we live in a highly interconnected, globalised world, and such a novel exists in many different languages across multiple editions. But I would say that despite the valiant attempt at carving out more ground for translation, this is still translation narrowly defined, translation as the process that results in what can be marketed by publishers as “a translation”. Portilla does however expand his discussion to talk of translation as an internal process: “cultural exchanges also take place in the literary work itself and, perhaps more importantly, in its process of composition” (p 119), but the context never leaves what I see as the relatively ‘safe’ territory of the contemporary novel. I want to address the issue of translation as a compositional methodology at the very birth of literature before globalization, before the existence of publishing editors and translation rights, by taking several more steps further, and asking whether we can conceive of any literature without translation, to see translation as the essential building block of any literary system. The proposition, in the words of the German poet Novalis (1772–1801), is that “in the end, all literature is translation” (Lefevere, 1977, p. 65). But, aside from being a nice self-affirming soundbite for us in TS, how might this actually be the case?

This leads us back to the history of literature, to literary beginnings, and by way of an illustrative example, to the recent compilation on this very topic: How literatures begin: A global history (Lande & Feeney, 2021). As the title suggests, the editors Joel Lande and Dennis Feeney aim in this volume at revealing the beginnings of literature; in doing so the book is geographically organised: we move from China to Japan to Korea, then to India, Greece, and the Latin of the Roman Empire, then onward to the Romance Languages. Africa is represented, as well as African American literature. The section on “World literature”, however, is almost a footnote, added to the back of the book in a derisory couple of pages; one can only presume that the world has, by this point late-on in the volume, already been traversed. Therein lies the problem: is not Chinese, or Greek literature also “world” literature? Well, not as scholars usually define it. The concept of world literature inherently involves a process of selection and exclusion, and to “world” is, as Hayot (2012) has noted, “to exclude” (p. 40). Perhaps predictably, the word “minor” does not even appear in the index of this history of literatures.

Fatefully, translation is usually conspicuously absent from discussion of literary genesis. In the conclusion to their conspectus, the editors seem almost aghast that something approaching translation may be a commonality to the emergence of literature across the globe: “One surprising result of looking at literary traditions individually rather than under a broader abstract category, as we’ve discovered, is that we come to see appropriation as the norm and not the exception” (Lande & Feeney, 2021, p. 382–383). This virtue of being “promiscuous in their borrowings”, as the editors put it, is surely a component of the bricolage of any literature system. Translation is not mentioned explicitly here, for nobody wants their national literature to be seen as having been translated, as derivative of something else. Even so, the spectre of the translated remains, the ghost at the global literary feast, for borrowing and appropriation are common metaphors for translation after the cultural turn (e.g., Kuhiwczak, 1990; Giust, 2017).

Rethinking translation’s role in the literature of the world would mean coming up with a different way of looking at literature: what would a history of literature (which is, I argue, a history of translation), look like if it were radically decentred? One imagines that it would be made up of case studies and evidence from a wide array of literatures and authors and traditions that do not appear in the usual collections. What if we looked out at the margins, and not necessarily always in relation to an imagined centre? What we need is, in the words of Eric Hayot (2012), “To come up with a better theory of the world, and of the relationship between the world and literature” (p. 41). The only way to redress the issue is to abandon any attempt at capturing the “world” and cast instead a more parochial gaze. What corners of the world have thus far been overlooked, and what can they tell us about literature and translation? I focus then in this essay on the ontology of a single-story tradition belonging to a single (minor) ‘literature’ that has not been added to any major compilation of world literature.

The problem of the role of translation in literary beginnings is similar to the problem of world literature as a whole: the context cannot be grasped in its totality. It is so far-reaching and nebulous that, under close scrutiny, it appears to dissolve into a fine haze. This is, presumably, the problem with what Blumczynski (2016) calls “ubiquitous translation”. What is required is a clearer focus, and this calls for a kind of telescopic approach. That which is distant must be magnified. We start off, then, by addressing the problem (How might translation beget literature beyond the production of world literature as a contemporary translational genre?), then we look through the telescope and begin to focus in on some greater detail. I posit that a detailed look at a single textual tradition belonging to a small, perhaps more recently developed literature would give us some idea of what happens at that embryonic stage. So, we begin with Asia and zoom in, to Zomia, that place populated with hill tribes that tend to resist state governance (Scott, 2009). Zooming in further, we see multi-ethnic southwest China, and the great river valleys of the Himalayan foothills. The focal length increases yet again, and the city of Lijiang comes into view. This is the cultural capital of the Naxi ethnic minority.1 With one final twist, the lens becomes temporal as well as spatial: maximum zoom.

It is late summer 2023, a school assembly room in Lijiang’s Old Town district, being used for a training class on Naxi culture aimed primarily at local Naxi scholars and students. Yang Yihong, a proponent of Naxi pinyin writing, is leading the class on a reading of the Naxi myth, the white bat’s search for the scriptures, a ritual text that tells of how the white bat was able to travel up to the heavens to find the books of divination and save mankind from illness. Nominally a ritual text to be chanted during religious ceremonies, it is here being read aloud via romanised pinyin (a Chinese term meaning “spell the sound”) transcription of Naxi language for pedagogical purposes (the students are all learning Naxi pinyin), but Yang Yihong makes sure to stress the entertainment value of the story: “This is really funny,” she says, “it’s something we can sit down and read, and when we do, we find ourselves laughing out loud”. This is new. The Naxi texts can be called a “ritual literature” (Yang, 2021, p. 160), that is, the ritual is the function of the writing. Can the ritual text be read purely for fun, outside of a ritual context? In this way, is it not evolving from “ritual literature” to “popular literature”? Or perhaps reading for entertainment is, judging from the number of educational books purporting to help inculcate such a habit in children, simply another kind of ritual. As the literature evolves, so does its associated rituals. The point here is that the story of the bat can be taken out of its limited, religious context and read for pure enjoyment. When the story is severed from ritual, it is free to become popular literature, as, “for literary myth-ritualists, myth becomes literature when myth is severed from ritual” (Segal, 2013, p. 266).

But why single out this story? Over recent decades, the stories found in the corpus of Naxi ritual manuscripts have been turned into long-form poems and translated in all kinds of more literal ways:2 the originals have been adapted, the overtly ritual elements taken away. Joseph Rock said that the love-suicide rite “lvbber lvssaq” (see Rock, 1939) could be listened to for entertainment, its tragic poignancy appreciated by simply hearing the tone of the chanter’s lament for the lost youth who commit suicide out of love. But nobody has before suggested that one could sit down and read the ritual literature for leisure. The white bat myth, at least as far as the Naxi ritual literature goes, stands apart. The books are not written in prose or rhymeprose, but instead a kind of loose notation of an oral chant, meant to accompany a specific religious rite. They were not originally intended to be decontextualised and read for fun, and, certainly, they were not meant to be read in Naxi pinyin by someone who was not a practising dongba ritualist.3 And yet here we are. The white bat story has a compelling narrative, and a hubristic hero who is something of a rakish joker. While the main characters in the other ritual texts barely have any kind of personality at all (the mythic episodes are retold in the rituals to convey the basic facts with only rudimentary narrative progression), the white bat is a more fully realized character. But where did this story emerge from? Why was the white bat given such a role? How did this myth become ritual literature, and how did it become popular?

It is not new to suggest that literature can be born from ritual. Stephen Owen (2000) has written on the ritual beginnings of Chinese poetry, specifically the Sheng min 生民 poem from China’s oldest poetry collection, the Book of Odes (Shijing 诗经):

The first thing that should be said about the Sheng min is that it is not a narrative poem; it is a ritual poem, and the fragments of a narrative that it includes are determined by the needs of authorizing the rite. (p. 26)

Chinese poetry began as ritual, then evolved into literary poetry. The Naxi rituals have taken a similar trajectory, only a less visible one, because of the more closed nature of the tradition as a whole. These are not exactly accessible texts; we can’t even write pictographic Naxi script on a computer without turning it into an image. We must remember that writing is not always a precursor to literature, for “not all languages attained a written form, and not all written languages immediately and ipso facto became literary languages” (Pollock, 2021, pp. 87–88).

This brings us to the thorny question of the textuality versus the orality of the Naxi literature. The Naxi texts occupy a kind of liminal space in between the oral and the written, in that oftentimes the books do not preserve a complete record of what is to be said. The Naxi manuscripts are not books as we might usually conceive of them. I defer to Charles McKhann (2010) for a generalised description of the Naxi manuscripts:

The pictographic manuscripts—written on long, narrow sheets of handmade paper, not unlike Tibetan books, but a little smaller and sewn along the left-hand edge—are not “texts” per se, for they are grammatically incomplete and therefore “unreadable” in the ordinary sense of the word. Rather, they represent a sophisticated mnemonic prompt for helping the dongba to recall long chants that are in the first place learned by ear and memorized. (p. 185)

All this is to say that we cannot really read a Naxi book. They cannot be read, at least as we understand the practice of reading, but the white bat story has nevertheless found a readership (at least in romanised or translated form). This is not literature in the sense of a “body of finalized, published written works belonging to a language or a people” (Schoeler, 2021, p. 192). The Naxi texts are not finalized, they are fluid. They do not have authors per se, they have scribes or copyists. Literature is something that may be defined or approached differently by different peoples over different time periods, and Yang Yihong clearly reads the Naxi bat text as literature, identifying a certain literariness within it.

Before a literary work can be translated from language A to language B, the proposed path from myth and ritual to literature requires a multitude of translations. The most important being a literarization, a movement that I envisage as traversing along a spectrum of actualisation. In their influential essay on folklore and the creative process, Jakobson and Bogatyrev (1980) adopt Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistic dichotomy of langue (the language system) and parole (performance via speech or writing) to discuss the essence of a work of folklore and its objectivization or performance (i.e., its becoming literature). For Jakobson and Bogatyrev, langue, i.e., folklore, exists only potentially, then it is made concrete in parole: the literary work. This straightforward movement from the oral to the written feels outdated, but, if viewed as two points on a wider spectrum of actualisation, I believe there is some value to the model. The Naxi ritual literature at least partially turns the langue of myth and folklore into parole (with the caveat that the transformation is itself not made on firm literary foundations in the semi-oral Naxi texts, it awaits further transformation). It is, to borrow another of Jakobson’s terms, an inter-semiotic translation. I intend therefore to connect Jakobson and Bogatyrev’s theory of this movement from langue to parole, from folklore to literature, to Jakobson’s theory of inter-semiotic translation of the verbal sign. Of course, Jakobson did not make this connection himself because his tripartite division of translation was based to a certain extent on Saussurean structural linguistics and therefore “does not cover semiotic transformations from intangible signs to tangible ones (i.e. from thoughts to texts) or from tangible signs to tangible ones” (Jia, 2017, p. 33). The gaining of specificity, the actualisation of a text, could also be seen as a movement from the intangible (langue) to the tangible (parole).

The borrowed

We can see this process of what could be called “literary actualisation” first-hand in the Naxi bat myth. It has become literature, but only after a series of translations: translation as borrowing, translation as bricolage, translation as a kind of building up, an embellishment. I aim to show several kinds of translation present in the origin and development of the bat myth as it moves from ritual to literature. Has the white bat been studied? Yes (see Rock, 1936; Huber, 2020; Liu, 2021), but only as folklore, as ritual literature, never as literature, be it prefixed with “world” or “popular”.

Where does the white bat come from? In its essence, the story follows the white bat as it is given the important task of saving mankind from illness by fetching the sacred scriptures from heaven, scriptures that will divine the reason and the cure for the pestilence. It is, in a way, the story of the genesis of book culture, contrasting with narratives among Zomian hill peoples about the loss of writing (Scott, 2009, p. 221–226). The white bat is known in traditional oral cultures across the Himalayas as a sacred messenger, a culture hero who mediates between the human world and the abode of the gods. The borrowed idea of a bat as culture hero is an intricately constructed gestalt of various traditions. Investigating the mythic motif of the bat as culture hero in the eastern Himalayas, we soon find in old Tibetan tradition that there is a “Great Wise Bat” (sgam chen pha wang) that may be analogous to the white bat of the Naxi ritual literature.

Toni Huber (2020, p. 108) argues that the oldest dateable narrative about the “wise bat” is found in the second volume of the gZi brjid (lit. “The Glorious”), a Bon text compiled in the fourteenth century that combines Buddhist-inspired teachings with indigenous Tibetan oral and literary traditions. In this text, the bat is one of the “thirteen Bon messenger birds” (bya bon phrin pa bcu gsum) who has necessary skills for a mission to act as a messenger to the gods. These skills are specifically listed as “profundity, words and discoursing, the three” (sgam tshig mchid gsum) (Huber, 2020, p. 108). He is chosen as the messenger precisely because he possesses those three abilities. In the Bon narratives, the bat is portrayed as eloquent and skilful, but also beset by an appearance deemed unacceptable to others: it is a hybrid creature and does not fit into clearly defined categories. In one episode, the gods draw particular attention to the bat’s unsightliness in what can only be described as a sort of group bullying. A whole host of one hundred male and one hundred female deities call the bat “A small man with a head like a rat […] such a sight as we have never before experienced, must be a bad omen from the earth” (Huber, 2020, p. 112). In this way the bat is perhaps a metaphor for translation; its nature is that of hybridity, and it is not generally accepted by mainstream audiences. In the Naxi myth, however, there is no such insinuation of unsightliness. The hybridity of the bat is nothing but celebrated. The bat doesn’t fit into normal categories, but this is seen as essentially laudatory, for it is sui generis.

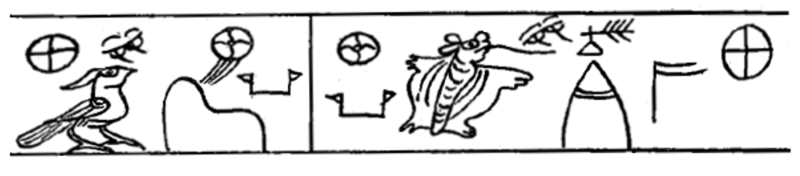

Figure 1. Extract from the white bat’s search for scriptures, (recreated from He & He, 1989, p. 244).

In the Naxi manuscript we see a repeated refrain: the bat speaks (we see this literally, for the bat ‘talks’ pictographically, a speech line emerges from the bat’s mouth). Its clearest attribute is the gift of speech. In fact, the bat chooses itself for the important mission of beseeching the gods purely because the bat believes itself to be persuasive, possessing the gift of gab (for the supposed profundity of the words tends to make way in the narrative for a more jocular style). Even so, the idea is the same as in the Bon traditions; the bat speaks, and good words emerge. The panel shown above in Naxi script (Figure 1) can be read (if we were to translate in a deliberately stilted, literal way) thusly: “and the white bat said, I have good message and profound message, three sentences, [and I can go up to heaven]”.

The Naxi words translated above as “good” and “profound” are ka and ee. Sgam (pa), one of the main qualities of the Tibetan messenger bat in the old 14th century source, means “profound”. The Naxi ee strictly means good, or goodness, but it can be understood as a profound kind of goodness, as Naxi scholar He Wanbao (2004) has explained: “ee is not the same as ka; ka is straightforward, easily understandable, whereas ee is a profound goodness, long-lasting, that can only be understood with time” (p. 17). Huber (2020, p. 116) notes that in classical Tibetan, the term tshig gsum commonly refers to a formal speech or address. Yet, in more everyday language, it specifically denotes a type of agency or the ability to take action, a trait highly esteemed in oral cultures. This concept is embedded in several succinct and popular Tibetan expressions (a genre of proverb that will be examined in the next section of the discussion).

When the bat speaks, then, it is with eloquence and profundity. This interpretation of tshig gsum can be traced back to the ancient traditions of the Bon ritualists, embodying a quality attributed to the bat, who not only acts as their legendary messenger but occasionally also as a supporting entity for those ritual practitioners. On the “three words”, Huber (2020) says that “Exactly the same idea occurs in Naxi myth motifs found in various dtô-mba [dongba] manuscripts” (p. 116). What do we call this usage of “exactly the same idea” across linguistic boundaries and beyond, through time and space, picking up new connotations along the way? It can only be translation.

Let us investigate exactly how this idea is translated in the Naxi tradition. The Naxi text clearly shows the bat saying he possesses “seel zhuq”, or “three sentences”. This is a literal translation of the Tibetan tshig gsum, by way of a Chinese borrowing (zhuq is a direct phonetic loan from Chinese ju 句, sentence). So Tibetan tshig (“word”, “talk”, “sentence”) equates to Naxi zhuq (“sentence”), and Tibetan gsum (“three”) is the Naxi seel (“three”). It refers back to classical Tibetan, having speech, having agency. The bat gets things done, he sweet-talks his way into getting hold of the sacred books; out of language, text, or perhaps we should say out of langue, parole.

Questions that may come to the audience (questions that the Naxi dongba ritualists would not be able to explain), such as “Why are there three sentences, specifically?” and “What are the sentences, anyway?”, find their explanation in this analysis. Simply put, “three sentences” is an old translation from the Tibetan, with metaphorical meaning beyond “three” being an auspicious number in Naxi culture. Unaware perhaps of the translational nature of this borrowing, Chinese translators (He & He, 1989, p. 245) have put the Naxi in Figure 1 into the following: “three good sentences spoken amongst the people” (renjian de san ju hao yan hao yu 人间的三句好言好语), at once over translating and missing the point—the profundity and power of the bat’s speech is not something that can necessarily be found among the common folk. Joseph Rock (1936) dispenses with the enigmatic number three altogether; translating the Naxi into “I am well informed and can speak well” (p. 42), which sounds almost like a rote answer from an unsuccessful job interview, and not the words of a spiritual emissary.

There is yet another level to the analysis, for ‘concrete’ poetry is added in the very act of writing the Naxi. If we zoom in on those three sentences in the Naxi pictographic writing, we can see two graphs, graphs that could almost be mirrored vertically:

Figure 2. Three sentences (fall as rain).

Here we see seelzhuq, three raindrops: each sentence, each expression, “falls like rain and descends like dew, like showers on new grass”, to paraphrase the book of Deuteronomy. Why raindrops? Because the Naxi for sentence, zhuq, borrows the graph for rain, read zhu, and, serendipitously, the graph for “rain” is comprised of three droplets of rain. In this case we have a pictographic borrowing, and the words become the rain, adding another layer of metaphor, another layer of translation.

It would be remiss of me to merely state this quality of ‘good speechifying’ without offering an example, and it is indeed this quality of the bat that, when exemplified, makes the text enjoyable to read, bringing it further away from ritual literature and closer toward popular literature. The gracious host in heaven above, the goddess of wisdom, asks the bat what he would have to eat or drink, and the tiny little bat, in a boastful mode, says that he can eat an entire mountain of the Himalayan staple tsamba, and drink an entire lake full of water. Of course, being a powerful goddess, she duly conjures up the mountain of food and the lake of water, and the bat, struggling to summit the epic promontory of roasted barley flour, slips and plops straight into the lake below. Much amused, the goddess fishes him out with her sleeve, and asks: “Why did you go into the lake?” to which the bat replies with a certain improvised bluster, “Well, I wanted to investigate how deep was the lake, and how high the mountain” (for, naturally, the most direct way to do this would be to dive into the lake from the top of the mountain). The goddess is amused, and laughs. Out of modesty she covers her mouth with her hand, and this, we are told, is why Naxi women cover their mouths with their hands when they laugh. The character of the bat begins to emerge in this story, and as Virginia Woolf (2008) said, the form of the novel evolved “to express character” (p. 42). This is not a novel, at least not yet, but it is nevertheless a stage toward literarity.

Figure 3. The bat, post impromptu bath, charms the goddess of wisdom (Rock, 1936, p. 47).

The bricolaged

So far, we have discussed only the character of the white bat, but not the narrative of the story. Investigating the story episodes of the myth, we will find that it is cobbled together from a number of sources: it is translation as a compilation of previous signs to create something new, a bricolage. A bricolage is a mixture of bits and pieces, and the story of the white bat is a mix of multicultural bits and plurilingual pieces. I follow Levi-Strauss (1966, p. 26) as seeing bricolage in this way as essentially a mythopoetic practice, but a practice that is at its foundation intercultural and translational.

While the nature of the white bat as an eloquent speaker may have come from religious sources, the story of how it makes its way up to heaven seems to be primarily inspired by secular folk wisdom. There is a legendary competition that is part of the folklore of the Tibetan hinterlands (specifically Khams and Amdo) concerned with the selection of the king of the birds, a competition in which the bat takes part. Two Tibetan proverbs relate directly to this competition. The first proverb can be translated as, “In the category of gems, jaspers are to be excluded; in the category of birds, bats are to be excluded”.4 The traditional story behind this proverb includes a test to be first to see the sunrise, but the bat and the garuda (bya rgyal khyung, the king of all birds) saw the sunrise at the same time. Another test is then arranged, this time to compare flying ability: who could fly the highest? The bat did not have powerful wings like the huge garuda, but it hid itself in the garuda’s feathers. The garuda flew above the other birds and loudly announced, “I have reached the sky”, after which the bat then flew out from its hiding place and said, “But look, I am above even you”. After discovering the bat’s trick, all the birds became very angry and unanimously declared, “How can this creature who has no feathers but instead grows horns, who has wings yet cannot truly fly, be fit to be our king? A despicable bird, mingling with the noble birds, is a disgrace to all bird-kind and a real laughingstock amongst the people” (Qiaga, 2006, p. 122). Therefore, the birds expelled the bat from their group and crowned the garuda as the rightful king of birds. Clearly, the hybrid nature of the bat singles it out for opprobrium. The first part of the proverb is perhaps an indicator of the colour of the bat: jasper is excluded from the taxonomy of gemstones, as bats are excluded from the taxonomy of birds.

Another proverb relates to that competition to see the sun, but this time it has a more decisive victor. This is the relatively well-attested saying: “All the birds look to the east, only the bat looks to the west”,5 an example of a proverb that represents the “popular knowledge and wisdom” of Tibet (Cüppers & Sørensen, 1998, p. ix), a proverbial composition of the kind known in Tibetan as kha dpe (translated as “mouth example”), that suggests a nugget of folk wisdom that intends to reveal some kind of common sense, and not necessarily religious truth. Its origins are unknown, but variations of this saying can be found across the Tibetosphere. What does it mean? In Amdo, for example, the proverb means to stand out from the crowd (i.e., to not blindly follow along), but the single line is connected with a specific piece of bat folklore, the aforementioned competition to choose the king of the birds. The story goes that when the birds chose their king, they agreed that whoever first saw the sunrise over the top of the mountain in the east the next morning would be declared the king of all birds. And so, the next morning, all the birds craned their necks to watch the top of the eastern mountain, waiting for the sun to emerge. Only the bat faced in the opposite direction. Because it faced west, the bat was in fact the first to see the rays of the rising sun in the east strike the summit of the western mountain, and thus the bat was chosen as the king of all birds. The proverbs are meant to pithily illustrate the bat’s cleverness (the former as a cunning trickster, the latter as simply wise), but these are still just tales disconnected from a grander narrative.

The Naxi tradition has developed a bat story that combines elements of both the above proverbial tales: the bat acknowledges straight away that it cannot fly up to the heavens, so a competition is arranged to see who will lend it their wings (who gets to ride on who). The competition is, of course, to spot the sun first, and the winner will get to ride on top of the loser. Just like the Tibetan proverb, this part of the story is supposed to reveal how the white bat outsmarts the larger bird that possesses a more impressive wingspan and gain a piggyback (garuda-back?) ride up to the heavens. In Joseph Rock’s (1936) translation, we are told:

The next morning, the Khyu-gu [Rock says that this is the wife of the garuda, but other versions of the story feature a golden eagle or the garuda itself], being ignorant, went up a mountain called Chu-na ngyu-shwua in the west to watch the sunrise, while the bat went to the top of Dtu p’er ngyu-shwua in the east. The bat saw the sun first, and the Khyu-gu later. Thereupon the Khyu-gu acted as the horse and the bat as the rider. (p. 42)

This extract is indicative of what amounts to a brief, pared-back translation, and when contrasted with the Chinese translation by He Limin, first published in 1989, we see that the competition in Rock’s version has been greatly simplified:

The two agreed on the terms, and the dull-witted, ineloquent golden eagle went to perch west of the river, facing the east, thinking that this would allow him to first see the morning light. The quick-witted, eloquent bat flew east of the river and sat facing the west. The next morning, the light of the dawning sun emerged from the white conch mountain in the east, falling onto the summit of the black pearl mountain in the west. The quick-witted, eloquent white bat was the first to see the morning light, and became the rider on the quest for the sacred texts. (He & He, 1989, p. 247)

The competition is a battle of wits, and therefore the extra details of how the bat was able to first see the morning light by facing to the west and seeing the sun on the summit of the western mountain is a better expression of the bat’s intelligence than simply going to the east where the sun rises; indeed, it closer reflects the Tibetan proverb, where the bat alone looks west, while all other birds look to the east. Rock fails to mention the direction in which the bat was looking, and the Chinese translations do more to emphasise the contrast between the bat’s intelligence and the eagle’s foolishness through parallel phrasing, a nuanced comparison lost in Rock’s simpler description of the eagle as “ignorant”.

But why would one translation be so much shorter than the other, given, presumably, equal amounts of respect for a ‘source text’? However we feel about these translations, they serve as an example of the multiform, non-fixed nature of oral tradition and translations that may be derived from it. The translators are not working on the same text. Each version is a translation of an individual performance which was itself based on a combination of written manuscript and an individual’s memory: there is no fixed source text from which to work. Rock’s simpler rendition could be attributed to the older, terser manuscript tradition, a less-skilled ritual expert performing the recital for him, a bad day at the office, or all of the above. Rock’s source manuscript is an early 18th century text that is stored in the Library of Congress’s Naxi collection. He’s source manuscript is a later text from the same ritual tradition, but that contains more characters (there is simply more ‘text’ to be read in He’s manuscript).

In Figure 4 from Rock’s manuscript below, we see the eagle sitting in the west and facing the east in the first section, and the white bat sitting in the east and facing the west in the second section. The scene has visual grammar that was left untranslated by Rock; the ritualist, perhaps more visually attuned, would have added extra detail in an oral performance.

Figure 4. The competition to be first to see the sunlight (Rock, 1936, p. 43).

Even in the right-hand panel of Figure 4 (above), the bat can be seen speaking, a speech line emanating from its mouth (speaking to nobody, generally the first sign of madness, but here presumably an extra reinforcement of the idea that the bat is clever, eloquent, profound). The large bird in the left panel remains tellingly mute.

The competition to see the sunrise is a story archetype found across greater Tibet, which sees its most elaborate development in the Naxi myth. It is adapted from folk knowledge, a piece of folklore, perhaps not by itself enough to be deemed literature. When syncretised into a concrete narrative, however, it starts to become more literary, and the Tibetan proverbs, via translational bricolage, turn into a Naxi story. If we view the folklore of the proverbs as langue, it is possible to see how it becomes parole in this bricolage:

Considered from the viewpoint of the performer of a folklore work, these [folklore] works represent a fact of langue; that is, an extrapersonal, given fact already independent of the performer, although admitting of manipulation and the introduction of new poetic and ordinary material. But for the author of a literary work, this [literary] work appears to be a fact of parole; it is not given a priori, but is dependent upon an individual realization. (Jakobson & Bogatyrev, 1980, p. 10)

All the possible readings are individual realizations of the cobbled together proverbs, or facts of langue. It is not simply the late arrival of interlingual translation that gives the story an increased text-ure; it is the diachronic addition of more detail, more text, in the Naxi manuscripts. The more recently written texts tend to have more written words, they may even be ‘grammatically complete’ (see Fang & He, 1981). Put simply, the text becomes more tangible. If “translation is viewed as something that enables the desirable and necessary passage from abstraction to concreteness” (Blumczynski, 2016, p. 139), then translation may also be theorised as a process of actualisation.

The becoming of books

The white bat story itself is not about the birth of literature, perhaps, but of something more fundamental, the birth of books, of written culture, of knowledge as transmitted by the written word. The story is an exemplar of the ability of the Naxi to adapt multiple cultural traditions into one gestalt, meaning that the bat in the Naxi tradition is the most comprehensive single bat narrative of all neighbouring peoples.

Eventually the bat acquires the scriptures, but it is nothing if not filled with hubris, and in its negligence drops the books right into the mouth of the golden frog (or a golden turtle). The frog-turtle (a Wittgentsteinian rabbit-duck)6 is killed, and its body and viscera become the foundation for all sorts of divination practices: notably, the five elements emerge from its innards, and its body becomes emblematic of the Chinese zodiac. It becomes a source text to be endlessly interpreted and re-translated. The frog-turtle is a cultural translation of the Chinese divine turtle, the shell of which was inscribed with the magic number square, the guishu 龟书 (“shell writing”). The mythical Naxi frog-turtle also becomes writing, writing that has the potentiality to one day become literature.

The myth takes on a more literary form in the late 20th century when Naxi author Sha Li reinterprets it within a Chinese language essay exploring the frog symbol’s significance on traditional Naxi women’s clothing. Sha Li embellishes the narrative with contemporary elements and incorporates Chinese cultural allusions. For instance, during the goddess of wisdom’s test of the white bat, Sha channels the spirit of contemporary anti-corruption efforts, describing the bat’s resistance to temptation as akin to an “upstanding cadre” withstanding scrutiny from the inspectorate: “The white bat recognised the goddess. He even rejected the temptation of great riches. Just like a modern-day, upstanding cadre who passes the questioning and investigations of the inspection department and anti-corruption bureau” (Sha, 1998, p. 36).

Later, when describing the great frog consuming the divination texts, Sha Li playfully references the classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West,7 contrasting the frog with the novel’s demons and the texts themselves with the delectable flesh of Tang Seng: “The great frog wasn’t some demon from the Journey to the West who’d been reincarnated in the sacred lake of the Naxi and was out to eat Tang Seng’s flesh, and the pages from dongba classics weren’t as tasty as Tang Seng either” (Sha, 1998, p. 37). These additions demonstrate Sha Li’s creative reimagining of the myth within a modern context.

I have previously written of how the dongba epics were reconstructed in Chinese via a process of analogy and translation, becoming analogous to Chinese myths and legends (Poupard, 2017). This is only half of the story, and probably the least interesting half, for the Naxi myths were translational reconstructions all along; they were born of translation. Jakobson and Bogatyrev’s formulation of langue and parole shares some similarity to Paul Ricœur’s theory of a text; Ricœur (1971, p. 144) sees speech and circumstantial reality “existing” in a state of presence, but writing as always suspended, outside circumstantial reality, until the text is “actualised” and made present by the reader-critic (“the text, as writing, waits and calls for a reading”). If nobody discusses the work, it never achieves a concrete reality—it remains the unheard falling of a tree in the deserted literary forest, making no sound. This is a problem of world literature; a text only exists in the category if it is fortunate enough to be discovered by someone: a reader or a critic; or of course an academic, if it is less fortunate. But I would like to see it also in light of langue and parole; if parole is langue made concrete, then the folklore can be further actualised by finding a readership, specifically, a readership beyond what would have been possible if it had remained in that narrower category of ritual literature.

Sha Li, Rock, and others operate as writers, yes, but also as readers/critics: they create more fully actualised versions of the bat text, with greater embellishments and more literary devices. A process of embellishment that is nothing if not translational. Out of langue into parole, out of obscurity and into a world literary canon. These movements are essentially ones of realising potentiality: the becoming of literature is an exercise in actualisation via a series of translations. Or, in other words, all literature is an entanglement of translation waiting to be unpacked, for the creation of literature begins in a vortex of stories. In the translated bricolage of these stories and ideas, the new Naxi white bat myth becomes nativised, always already Naxi.

Gentzler (2017) has called for a rethinking of translation, “not as a short-term product or a process, but as a cultural condition underlying communication” (p. 7). I have tried to theorise the genesis of the white bat story, its turn toward literature, as both intersemiotic translation (i.e., the movement from myth to literature or ‘folk wisdom’ to literature) and more traditional interlingual translation (from Tibetan to Naxi, or from Naxi to Chinese), but above all, as a translation from a less actualised to a more fully actualised literary form, a process that is inherently interlingual and intercultural. In any case, translation-as-cultural-condition sounds too broad to grasp, unless we narrow our focus, and this leads me back to the crux of the matter. We need less theorizing of what can be termed major, and more focus on the un- or understudied. This essay has been a response to How Literatures Begin by imagining a chapter on Naxi literature. It would ideally be bookended by a chapter on Tibetan literature, and perhaps a discussion of Baima 白马 literature, that Tibetan people of Sichuan who are not a recognised minority in China but who nevertheless have their own literature and their own related version of the bat myth (Zhang & Qiu, 2015). Translation scholars are uniquely placed to bring minor literatures of the world to the fore: to translate in every sense of the word (textually, exegetically) these literary systems and build up a fuller picture of world literature.

This could be deemed part of the “outward turn” (Bassnett & Johnston, 2019), a metaphor for a new paradigm in TS, but let us literalise the metaphor: a turning away from the centre. When our attention focuses on the smaller literatures of the world, more may come into view. Like the clever bat in the pan-Himalayan tradition, perhaps to spot the light and be thus illuminated, we must look in the other direction, the direction in which nobody else is looking. And with that, a happy by-product of said turning away: a clearer focus on voices that add to the plurality of the human experience.

Figure 5. Ideographic rendition of the Tibetan proverb “When the other birds look to the east, only the bat looks to the west” in Naxi script.