In November 2014, a teaser trailer heralded the return of the Star Wars universe. A lengthy shot of an empty desert, rapid flashes of new characters, and glimpses of semi-familiar iconography generated a tension and intrigue accented in the music by eery brass stingers and whirling strings (Star Wars 2014). However, any apprehension and fear soon dissipated for the centrepiece: a theatrical shot of the Millennium Falcon accompanied by John Williams’s thunderous “Main Theme”. Seemingly trumpeting the derring-do of the Falcon, the famous fanfare simultaneously announced the awakening of the once dormant franchise1. So potent was the effect of the teaser, that Patrick Willems, in a video called “How STAR WARS Trailers Weaponize Nostalgia”, described this moment as “a pure rush of euphoria” and a “hit of visual and auditory nostalgia straight to the pleasure centres of our brains” (Willems 2019).

For the official Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (J. J. Abrams, 2015) trailer, this nostalgia-inducing technique continued with a unique string arrangement of “Han & Leia” marking a similar shot of the Falcon (Star Wars 2015b). A prominent musical theme of George Lucas’s original trilogy (1977–1983), “Han & Leia” had gone unheard in the prequel trilogy (1999–2004). While, like the preceding teaser, the eventual arrival of the “Main Theme” suggests an epic adventure in the Star Wars universe, the statement of “Han & Leia” traffics in different emotions. The love theme does not accompany a shot of the smuggler and princess whom it typically signifies, rather semantic consistency is side-lined in favour of maximalising the affective power of the theme for fans. In this context, “Han & Leia” acts a device to suggest nostalgia, reminding fans of the “glory days” (Goldberg 2012).

Commonly exploited in advertising (Routledge 2016, 39), nostalgia has come to define the look and sound of trailers for long-awaited sequels and reboots (see also Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny [James Mangold, 2023] and Jurassic World [Colin Trevorrow, 2015]). Within such “legacy films”, as they are dubbed by Dan Golding (2019, 69), thematic recall serves specific functions: marking a return, indicating narrative continuity, signifying the narrative past, and often reminding us of our fondness for that past. Even when returning actors have aged and the slick filmmaking of today marks an aesthetic departure from franchise origins, familiar associative themes can expediently offer the illusion of continuity and resummon emotions associated with an idealized past. Evidently aware of the capacity of music to grasp “the nostalgic experience” (Davis 1979, 29), Disney and Lucasfilm placed a particular weight on Williams’s original themes when advertising the sequel trilogy.

So significant was nostalgia to marketing The Force Awakens that, atypically, Williams himself recorded the music for the first teaser2. “Disney felt that it was really important that audiences continue to feel like all the music that you heard [in the trailers] was [Williams]”, Star Wars trailer composer Jacob Yoffee has detailed3. This desire for stylistic emulation and the frustrating uncertainty of studio executives—offering vague notes like it “needs 15–20% more emotion”—made the composition and selection of trailer music a ruthless process for those competing for potentially career-making “placements”. With the benefit of hindsight, and after overviewing teasers and trailers, it becomes clear that Disney valued “Force” above all else. However, that thematic centrality only arrived after most other themes had been tested and rejected. For example, an eleventh-hour “Yoda” trailer track requested of Yoffee was mostly discarded by the film’s director J. J. Abrams who “didn’t recognize the theme” immediately4. It was for similar reasons of identifiability that a Williams arrangement of “Rey”—an intended thematic introduction specifically composed for the second teaser—was left on the cutting room floor. Evidently, for trailer producers and marketing executives new themes do not sell new films. In Yoffee’s words, “they ended up not using it purely because—if you think about it—no one knew “Rey’s Theme” yet. So, it didn’t have the nostalgia. Nostalgia is a really tricky thing.”

These trailers, marketing strategies, and Yoffee’s words explicitly acknowledge that which concerns this article: the nostalgification of Williams’s original Star Wars trilogy music since the Disney acquisition of Lucasfilm in 2012. While in the new age of Star Wars Williams’s baton has passed to the likes of Michael Giacchino, John Powell, Ludwig Göransson, Joseph Shirley, Nicholas Britell, Natalie Holt, and Kevin Kiner who each invoke the classic music of the series to varying degrees, I focus on Williams’s own music for the sequel trilogy: The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017), and The Rise of Skywalker (J. J. Abrams, 2019). The continued reiteration of familiar musical ideas in this trilogy will be shown to emblematize a more widespread culture of nostalgia. I demonstrate this nostalgification by contextualizing specific scenes as part of a sentimental scoring practice, a conservative film aesthetic, and broader industrial trends. This focus also necessitates a reassessment of the composer’s motivic practices. In this light, I position Williams as an adopter of the reminiscence motif (that associative musical device of opéra comique) and not just as an inheritor of the Wagnerian leitmotif (as is often acknowledged). Representative examples are not discussed chronologically but are rather grouped thematically, moving from the original and affecting to the heavy-handed and uninspired. Subjective as such assessments may seem, the potential effectiveness of these nostalgic endeavours is understood through my critique of the sequel trilogy’s historiography, a thread which runs parallel to my principal focus on motivic recall and nostalgia. Yet first it is necessary to define nostalgia more broadly and contextualize its function in the wider Star Wars series.

Nostalgia and Star Wars

The narrative sentimentality of the Star Wars sequel trilogy falls under Svetlana Boym’s category of “reflective nostalgia”: defined as “linger[ing] on ruins, the patina of time and history, in the dreams of another place and another time” (2001, 41). This reflective perspective is most evident when one looks at the legacy characters, who now dwell on the past and their mistakes. They are no longer the optimistic heroes of their youth but filled with regret (Han and Leia are estranged and have lost their son, and Luke has exiled himself to a remote island). Simultaneously, the filmmaking itself might reflect Boym’s concept of “restorative nostalgia”, “attempt[ing] a transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home” (Boym 2001, xviii). In this case, the original trilogy is invoked through a return to practical effects and the re-treading of familiar narrative beats. This restorative aesthetic “reinvents the feel and shape” of the past in an attempt to “reawaken” it (Jameson 1997, 197), and thus to reappropriate the esteem in which it is held.

Such nostalgic tendencies are an inherent component of the “legacy film”, as Golding has argued (2009, 69–83). Noting the example of The Force Awakens among others, Golding observes that studios searching for “financial dependability and predictability” frequently rely on the “nostalgic currency” of dormant late-twentieth-century franchises (2009, 69). Just as risk-averse studios attempt to recapture old glories via legacy characters and familiar narrative concerns, so too are associative themes recalled to emphasize familiarity. In many of these legacy films, one can find that recognizable themes are delayed, only reappearing to accent a souvenir (character, location, object) of the past. In such scenes, the camera might even linger on the lost object which has now been found, allowing a revived theme to announce the return: such is the case with the reveal of the theme park in Jurassic World and many Star Wars moments discussed shortly5. These instances are clearly directed at fans and often do not serve any specific narrative function.

Of course, it is not merely contemporary legacy films that revel in nostalgic sentimentality. After all, Fredric Jameson coined the term “nostalgia film” with regard to George Lucas’s original Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) and his preceding film, American Graffiti (1973). For Jameson, A New Hope facilitated and gratified a “nostalgic desire to return to that older period” defined by science-fiction serials of the 1950s as well as the Flash Gordon comic strips of the 1930s; and American Graffiti enabled a similar return through cars, fashion, and rock ‘n’ roll (Jameson 1997, 197). However, Lucas’s referentiality was not as limited as Jameson suggests. The original Star Wars also shows clear debts to westerns, World War II aerial combat footage, Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress (1958), and historical adventures films like Captain Blood (Michael Curtiz, 1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (Michael Curtiz and Wililiam Keighley, 1938), and The Sea Hawk (Michael Curtiz, 1940). As a pastiche of these multiple genres and a more overt revival of the sci-fi B-movie, A New Hope reflected Lucas’s own nostalgic longing, one, to use Boym’s words, “defined by loss of the original object of desire, and by its spatial and temporal displacement” (2001, 77). While the director’s attempts to revive and refashion were evident in the generic character archetypes, the grandeur of the heroes’ adventures, and the child-friendly tone, the sense of return was heightened by the music. Lucas’s very conception of the score was in terms of the classical Hollywood vernacular: “it’s an old fashion kinda movie and I want that kind of grand soundtrack they used to have on movies” (Lucas, quoted in Audissino 2021, 73). So entwined was the “old-fashioned swashbuckling symphonic score” (Williams, quoted in Dyer 1997) with the traditions and techniques pioneered by film composers Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold that Emilio Audissino dubbed Williams’s renewed style “neoclassical” (2021, 139–157).

Williams’s revival of that “emotionally familiar” sound (Williams, quoted in Byrd 1997, 18) has been discussed by many scholars (including Kalinak, 1992, 188), but it is Caryl Flinn who has addressed the score in relation to Jameson’s idea of nostalgia and pastiche. In making the frequent melodic comparison between Williams’s “Main Theme” and Korngold’s music for Kings Row (Sam Wood, 1942), Flinn notes that their similarity reveals how “contemporary cultural production actively banks on the utopian value that earlier, ‘classical’ American culture—especially cinema of the 1940s—holds for us” (1992, 153). Similarly, the stylistic influence of Miklos Rózsa’s Ivanhoe (Richard Thorpe, 1952), a temp track in A New Hope (Hirsch and Sadoff 2023, 14), further illustrates this backwards gaze. While this already nostalgic “Main Theme” and opening crawl resummoned notions of older media, we might now view this formal convention as doubly nostalgic. In the collective breath between “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”, the B-flat major chord, and the screen-filling title, this ritualistic introduction recalls both storytelling conventions of serials and B-movies as well as every Star Wars adventure we have had before6. As the fanfare and crawl remind us of the past, contemporary audiences might also become aware of the veritably antiquated neoclassical sound, one that is increasingly outmoded in the contemporary Hollywood of Hans Zimmer and Remote Control Productions and which, thus, might be all the more effective at encouraging nostalgia.

Musical reminiscence

While this article critiques the often excessive musical nostalgia of the sequel trilogy, it is worthwhile initiating this study with—arguably—one of the most successful moments of musical sentimentality in the saga. At the climax of The Last Jedi, Luke and Leia reunite for one final time. Williams’s score facilitates a great deal of unexpressed emotion during their “wordless exchange, conducted via leitmotif” (Ross 2018). In the scene, Luke returns to stave off incoming attacks to give the surviving members of the Resistance, his sister included, an opportunity to flee. But before facing down the First Order, the aged Skywalker twins have a brief reunion, underscored in celli by the returning “Luke & Leia” theme. Given that the characters of Luke and Leia (and at a more meta level the actors Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher) had not appeared on screen together since 1983, Williams had little reason to revive their representative theme leading up to this point7. By virtue of its extended absence (four films or thirty-four years), “Luke & Leia” possessed a particularly affecting quality in this scene. Unlike most other leitmotifs of the series, “Luke & Leia” had been developed little and thus was perhaps relatively unknown in comparison to pervasive themes like “Force” and “Han & Leia” which also appeared in this cue, “The Spark”. Despite the relative obscurity of their motif, it still retained clear associations given its original appearance when Luke reveals to Leia that they are twins and given its dedicated concert arrangement, simply called “Luke and Leia”. Not resigned to the classification of an “incidental motif” like Williams’s other associative musical material (see Lehman 2023 for a full list), here, “Luke & Leia” might be more appropriately classified as a reminiscence motif, a precursor to the commonly discussed Wagnerian leitmotif and a characteristic device of opéra comique following the French Revolution.

Given their relative scarcity, reminiscence motifs (or Erinnerungsmotivs) lacked the broader accumulation of associative significance and the musical development common to the leitmotif, instead functioning “to signify recollection of the past by a dramatic character” (Grove Music Online 2002). The reminiscence motif and leitmotif differed, in other words, in the scale of their deployment and in the distinctive capacity of the latter to assume a form-building function (as in Wagner’s music dramas). Reminiscence motifs worked effectively in large scale works like operas where their restatement could serve as a device of dramatic recall and to mark moments of importance. As outlined by Jörg Riedlbauer (1990, 21), models of such motifs can be found in the works of Étienne Méhul, as well as those of André Grétry, Charles-Simon Catel, Nicolas Dalayrac, Heinrich Dorn, Luigi Cherubini, and Jean-François Le Sueur.

According to Matthew Bribitzer-Stull, in order for such a motif to function, two stages of deployment are essential: “presentiment and reminiscence” (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 72). The first appearance establishes the musical material and suggests extra-musical associations. This primes our memory and marks a theme as meaningful through a statement at a significant narrative moment. To form associations in the presentiment stage, Bribitzer-Stull notes the importance of “temporal coincidence and topical resonance” (102). The former requires the music to correspond to the “visualizable”—a “prop” or concept we can imagine—with some degree of temporal proximity (104). The latter strengthens association by requiring the music to have some similarity to “topics native to the culture at hand” (106); this can be accomplished through a composer’s use of mimesis, a familiar expressive genre, or the perpetuation of a codified trope which generates a clear connection between the musical and non-musical. Following presentiment is the moment of recall. This is where the motif re-sounds after some time and brings with it the established association to fulfil some dramatic function, thus clarifying the emotions of the earlier statement. In this moment, the theme “staddle[s] the past and the present” (107), effecting the recall of some distant memory, stirring the listener’s consciousness, and identifying the moment as one of dramatic or emotional consequence.

While Carl Maria von Weber has been noted for developing the reminiscence motif (Riedlbauer 1990, 24), for the purposes of this study it is perhaps worthwhile giving an example from Wagner—a commonly cited point of influence on Star Wars music (albeit one Williams has professed little affection for; see Ross 2020). Wagner himself has addressed relevant ideas of musical presentiment and reminiscence. He noted that

the vital centre of the dramatic expression is the verse melody of the actor: it is prepared for by the pure orchestral melody as a foreshadowing, and from the verse melody derives the ‘thought’ of the instrumental motive as a reminder. (Wagner, cited and translated in Riedlbauer 1990, 26)

In addition, he observed that

return(s) in the orchestra in regard to earlier dramatic situations [can furnish the] significance of a strong reminder. (Wagner, cited and translated in Riedlbauer 1990, 26)

Motivic reminiscence is a pervasive feature of his operas such as Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser, however the Frageverbot motif of Lohengrin will serve as a representative example here. The motif is associated with the forbidden question since it is first sung as Lohengrin requests that Elsa, his betrothed, never ask his name. Throughout the opera, restatements of Frageverbot selectively punctuate the drama: maintaining and reinforcing associations as the villainous Ortrud plots, when she asks Elsa about the mysterious Lohengrin, to underline Elsa’s anxieties, and to mark Ortrud’s premature triumph. In Act 3, when the insistent Elsa finally asks the forbidden question, Frageverbot reaches an apotheosis, resummoning the memories and associations of its first statement that were carefully reinforced throughout the opera. Lacking musical and semantic development, Frageverbot is not a leitmotif like those of Der Ring des Nibelungen or Wagner’s other music dramas. Instead, Wagner referred to it as “a reminiscence of Lohengrin’s prohibition which has hitherto been clearly imprinted upon us” (Wagner, cited and translated in Unlocking Musicology 2019)8. With this capacity as a device of recall and Wagner’s own acknowledgement of this functionality, the reminiscence motif label seems most apt to both Frageverbot and “Luke & Leia”.

My acknowledgment of this model is not intended to further paint Wagner as an influence on Williams nor to suggest that Lohengrin was a point of emulation. Rather, the use and effect of “Luke & Leia” in The Last Jedi suggest a parallel to this eighteenth- and nineteenth-century musical practice. Yet, here, that intra-operatic device has now become an inter-filmic device, and, given the elapsed time between the three trilogies, the gap between presentiment and reminiscence has been taken to an extreme. As a result, “Luke & Leia” not only marks the reunion and underlines the emotionality of the scene but, moreover, generates a quite distinctive nostalgic affect. This long-delayed motivic restatement functions on multiple levels: within the film, it signifies the culmination of narrative and character arcs; within the series, it marks temporal displacement; and beyond the series, it—alongside Luke’s line “No one is ever really gone”—might point to the tragic and untimely passing of Carrie Fisher9. This moment of musical reminiscence is markedly effective not solely due to these discrete and cumulative layers of nostalgia but rather because nostalgia is not the sole motivation behind motivic recall.

Additionally, the reminiscence motif label taps into an aspect of Star Wars music addressed by James Buhler, who observes that Williams’s themes often function to mark the passage of time (2000, 53). In observing the motivic desire to return to the semiotic “stability of origin”, Buhler addresses the devolution of the leitmotif in Williams’s scores: in prioritizing clear signification, they are demythologized. The leitmotifs of Star Wars develop little and only ever briefly change to “communicate semantic content” (53). However, the scarce “Luke & Leia” seems to capitalize on this basic linguistic signification. This reminiscence motif perhaps serves a noticeable mythopoetic function precisely because of its ability to mark time, to point to a singular moment. Rather than seeking “to escape the eternal flux of myth” (54) like many Star Wars leitmotifs, the reminiscence motif mythologizes by virtue of its transience, its effect of momentarily signifying narrative change without fundamentally changing itself. In signalling its “baptism” (London 2000, 87), this recall of “Luke & Leia” resummons the moment at which Williams’s leitmotifs are at their most mythic, the moment of “presentiment”. Yet, this mythopoetic capacity is not always evident in themes which might appear to claim the label of reminiscence motif.

Earlier in The Last Jedi, during “The Battle of Crait” cue, Williams re-stated “TIE Fight Attack” from A New Hope. A clear nod to the original musical context, the citation pointed to a similar chase sequence wherein the Millennium Falcon is pursued by enemy fighters. Simultaneously, the mise en scène echoed the asteroid field chase from The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980), a sequence depicting aerial acrobatics in tight and cavernous spaces. Accordingly, this musical restatement little highlights what is new—the different location, the new characters, new musical themes—and instead accents self-evident parallels. Mythopoesis made manifest and thus redundant, this reminiscence motif seems to scream “listen to me, for I am telling you something important” (Buhler 2000, 43). Unlike “Luke & Leia”, the function of recall here is reminiscence, rather than this emotion arising as a side-effect of present thematic associations10. Elsewhere in The Last Jedi, Williams uses recall in a more playful manner, almost in the vein of a musical Easter Egg: a “hidden reference” which communicates “extra information to the informed viewer” (Edgar 2019). For example, the “Death Star” motif returns to accompany a visual gag in which an iron pressing First Order uniforms is briefly framed like an imposing Imperial Star Destroyer; savvy listeners are thus rewarded with an additional gag informed by the referentiality and connotations of the menacing motif. The musical signifier of a planet-destroying space station is juxtaposed with the iron, a contrast inviting laughter11. Such instances of recall are not grounded in the same emotional complexity as “Luke & Leia”, a difference which works in favour of the citation of “Death Star” but not of “TIE Fighter Attack”.

At this point it is also worth observing that not all musical references are decided and controlled by Williams. Over the course of the series, editors have recycled Williams’s pre-existing Star Wars music. This procedure is one of the prequel trilogy as much as of the sequel trilogy and seemingly a side-effect of digital editing procedures as Chloé Huvet has observed (2022, 198) and as Nicholas Kmet has demonstrated (2017). This repeated manipulation of Williams’s music has also often earned the ire of the fandom (Huvet 2022, 215–219). A noticeable example of editorial reuse is at the climax of The Force Awakens, where the statement of “Force” from Williams’s original cue (“The Ways of the Force”) is replaced by one from “Burning Homestead” of A New Hope. That thematic statement which first accompanied Luke’s mourning of his aunt and uncle now sounds as Rey uses the Force to retrieve Luke’s lightsabre. Such musical reuse seems to connect the two moments. Indeed for Golding, three forms of citation become evident in The Force Awakens scene: the recurring “embrace the call moment” from Joseph Campbell’s heroic monomyth, the reuse of Williams’s A New Hope cue, and the quotation of the Dies Irae which follows “Force” (Golding 2019, 127)12. Golding argues that these points of similarity become meaningful “in aggregate” and that this is not “simply an easy recycling of successful material as some critics claimed” (2019, 127–28), but instead a more nuanced, musically marked, thematic parallel. While such layers of analogous meaning may have arisen by virtue of this repetition, I doubt they were intended. Rather, I maintain that Williams’s original cue was replaced for some perceived lack and was substituted with a “Force” statement of proven affective capabilities. This was likely not for any nostalgic purposes per se but instead for the safety offered by its familiarity. Yet as Golding’s discussion testifies, such instances of musical recycling will invite comparison regardless. With this example, it is evident that musically facilitated nostalgia or reminiscence does not solely arise based on the work of the composer and may be prompted by post-production procedures. Furthermore, motivic recall often seems to be pre-ordained by the screenplay itself, as some of the following examples indicate.

“That was a cheap move”

With The Force Awakens, director J. J. Abrams and co-writer Lawrence Kasdan created a meaningful beginning for a new generation and appealed to the sensibilities of long-time fans. While some derivative character archetypes and formulaic plot conventions were the subject of criticism, this familiarity was intended and a means of assuring fans that “nothing has changed really”, as Mark Hamill noted in a promotional sizzle reel; he qualifies that “everything’s changed, but nothing’s changed” (Star Wars 2015). In returning to known themes, characters, and narrative beats, the sequel trilogy often actively revelled in the familiar. This permitted Williams to savour certain motifs in order to exaggerate and aggrandize any visual echoes or call-backs. An early and pertinent example is the reveal of the Millennium Falcon.

Described first as a “piece of junk” by Luke in the original film, the ship similarly held little value for Rey, Finn, and BB-8 when they stumbled upon it during the first act of The Force Awakens. Rey, like Luke, remarks that the ship is “garbage” but the filmmaking says otherwise. Instead of underlining our heroes’ panic and fear, the establishing shot of the Falcon markedly lingers on the ship for a beat while the celebratory “Rebel Fanfare” “elicit[s] nostalgia and excitement” (Audissino and Huvet 2023, 700). As the Falcon did not have a specific motif, the returning theme gives the ship’s reintroduction the musical familiarity it might have otherwise lacked. Indeed, many motifs are delayed in The Force Awakens until such a moment where they might heighten nostalgia, including “Imperial March”, “Main Theme”, “Force”, “Leia” and “Han & Leia”. For example, the “Main Theme” first sounds in the narrative as Han and Chewie return to the Falcon, accompanying Han’s line “Chewie, we’re home”13. To compensate for its lack of a musical signifier, the Falcon veritably re-appropriates “Rebel Fanfare”. The theme is thus endowed with the function of haloing the ship in a nostalgic glow. Laura McTavish even proposes that “the theme could almost be renamed ‘The Falcon’s Theme’… as it almost exclusively accompanies scenes involving the iconic ship” (2023, 124). McTavish’s use of the word “iconic” indicates the prestige lent to such objects of the original trilogy and the expectations placed upon their return.

This retention of pre-existing music to maximalise fans’ emotional reactions is characteristic of Disney’s Star Wars. Now burdened by metatextual duties, Williams’s music sometimes operates in a manner that disrupts semantic consistency and undermines the narrative present. In observing this, I do not wish to say that the composer’s themes have always signified rigidly or uniformly. One instance of such “dramatic license” (Williams, quoted in Rinzler 2007, 268) is the affecting string statement of “Princess Leia” for Ben Kenobi’s death in A New Hope: a moment where the “wildly romantic” nature of the theme superseded its established semantic associations (Williams 1977)14. For the composer, it is evident that musical semantics can be sacrificed when a theme is serving a greater emotional imperative. However, for the sequel trilogy, these semantic ruptures are not always focussed on emotions of the present narrative moment, instead favouring the past in a manner which bears more resemblance to marketing campaigns than Williams’s established aesthetic. These nostalgic affectations and a “commitment to homage and revival” can leave a film “without meaning of its own” (Golding 2019, 67). With the attempts of the sequel trilogy to appeal both to new and established fans, music becomes trapped between serving the current emotional narrative and trying to remind fans that “nothing has changed really.”

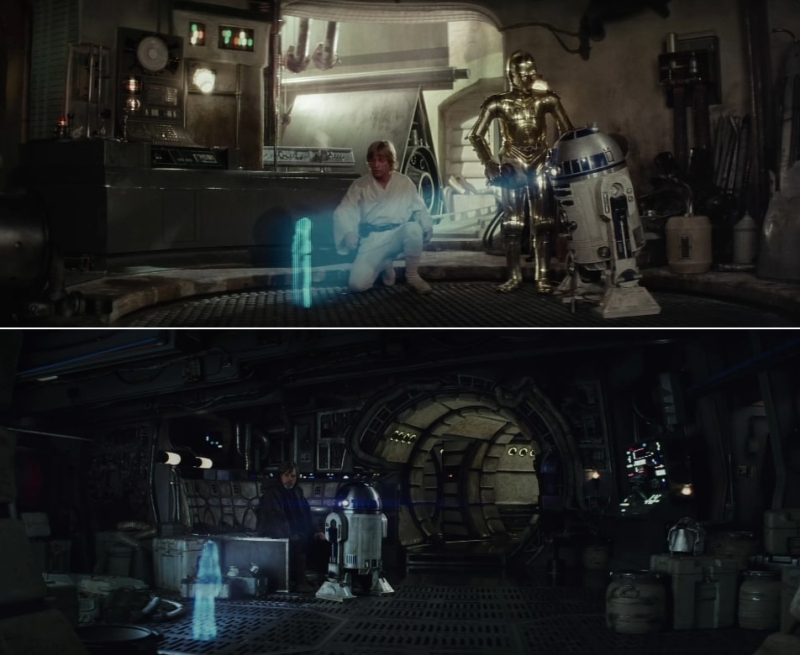

As previously noted, sequences built around nostalgia often appear to be wedded into the narrative structure of the films. While The Last Jedi seems aware of the “cheap move[s]”—as Luke says to R2-D2 after the droid replays the famous “Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi, you’re my only hope” speech—that does not diminish their frequency. As expected, the return of the Princess Leia hologram designates a sentimental restatement of the “Princess Leia” motif in the soft woodwind and strings redolent of the A New Hope cue “The Princess Appears” (Figure 1). Such unabashed nostalgia contrasts the film’s pretentions with “let[ting] the past die” and its attempt at thematic progression—to move beyond the simplistic good-and-evil binaries and the focus on the Skywalker lineage. However, despite concerns with evolution in The Last Jedi, Williams’s score was among his most conservative in terms of thematicism. In testament to that fact, Lehman’s Thematic Census (2023) has indicated that of all the scores The Last Jedi was the most reliant on the popular “Force” theme. Perhaps this overwhelming reliance on the familiar was a side-effect of director Rian Johnson’s atypical temp-tracking procedure. In an interview on the film’s music, the director described that,

When we were editing, we had a very talented music editor, Joe Bonn, who cut a temp score out of John’s previous scores and we basically temped using John Williams’s music. And then basically we gave that temp score to John and that was our spotting session. You know, a spotting session is usually when you sit down with the composer and talk through what you want. I didn’t do that with John, just gave him our temp score and said this is generally the shape. And then John took that and sometimes he went with it, sometimes he deviated from it, but he just did his thing; and the first time I heard any of the music John had written was when we were on the scoring stage. (Johnson in Soundtracking with Edith Bowman 2017)

Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that Williams would return to established motifs so frequently given that they acted as a template before composition commenced, and that the otherwise progressive director elected to have minimal musical input.

Figure 1

Princess Leia Holograms: A New Hope, Luke stumbles across Princess Leia’s plea for help (above); The Last Jedi, R2-D2 reminds Luke of Leia’s message (below).

© Lucasfilm; 20th Century Fox

As a consequence of its prevalence in The Last Jedi, “Force” is less often motivated by its typical signifieds (the Force, the Jedi) or by legacy characters, settings, and mise en scène. Occasionally, it bears no obvious semantic relevance to the narrative: for instance when Luke sneaks aboard the Falcon, as Finn and Rose access an enemy ship, and when Finn rouses the troops before the final battle. Given this overuse, one feels that the affective power of the theme is diminished and that it has lost a degree of semantic specificity, now becoming a lackey ordered to fill in musical space. The prominence of this theme in The Last Jedi demonstrates a musical imbalance that, for Buhler, holds narrative meaning: “its constant musical presence serves to remind us that, though the Resistance is much diminished, the Force spreads its power wide” (Buhler 2018). As with Golding’s view of “Burning Homestead” in The Force Awakens, I believe Buhler was perhaps being overly charitable. Where he sees narrative meaning in thematic saturation, I see an overdependence on the established thematic tapestry. Of course, the Force and its theme have become an engrained component of the series, with frequent thematic repetition providing a sense of continuity and musical form across the three trilogies. “Force” might even be the musical representative of the Skywalker Saga, acting, in Lehman’s view (2023), as an “All-Purpose theme”15. One need look no further than the four binary sun sequences and their prominent statements of “Force” to recognize its structural significance: in A New Hope, it marks Luke’s longing for adventure and hints at his destiny; in Revenge of the Sith, it initiates his story; in The Last Jedi, the (potentially imagined) sunset concludes his story; and, it manifests again in The Rise of Skywalker as Rey identifies herself as a Skywalker, appropriating Luke’s legacy (Figure 2). However, the increased reliance upon this familiar staging and the theme might just represent another form of oversaturation.

Figure 2

The four Binary Sunsets: Revenge of the Sith, Baby Luke is given to his aunt and uncle (top); A New Hope, adolescent Luke senses the call to adventure (second from top); The Last Jedi, elder Luke becomes one with the Force (third from top); The Rise of Skywalker, Rey and BB-8 return to Luke’s home on Tatooine (bottom).

© Lucasfilm; 20th Century Fox; Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

The recurring iconography has acted as a visual reminiscence motif throughout the series, explicitly recalling the mythic origins of Luke’s adventure during key narrative moments. As with musical reminiscence motifs, power is lent through absence, the temporal distance between statements, and the lack of development, each helping to accent emotional resonances upon recall. Yet, one might argue that the binary suns marking Luke’s death in The Last Jedi acted as a successful bookend and that the subsequent repetition in The Rise of Skywalker was a nostalgic step too far. While “serial nostalgia becomes part of the diegesis” (Golding 2019, 184), such continued reuse risks turning the iconic into a cliché. Rather than establishing a new motif—visual and/or musical—to mark the end (or a beginning) of Rey’s journey, The Rise of Skywalker resorted to another “cheap move”. Effective though the binary suns may be, their repetition is emblematic of something greater: that filmic and narrative reminiscence are so entwined in the sequel trilogy that the films occasionally collapse under the weight of nostalgia and sacrifice their autonomy for reflection.

Williams’s “exception” becomes the rule

While much of the musical nostalgia in The Last Jedi was the result of textual and visual echoes, in The Rise of Skywalker nostalgia was a veritable raison d’être. At this point, it is worth positioning The Rise of Skywalker as the principle victim of the studio’s lack of forward-planning. Its key creatives Abrams and Chris Terrio were hired as last-minute replacements during pre-production, stepping in after the previous director’s “visions for the project differ[ed]” from those of Lucasfilm (Disney, quoted in McNary 2017). Hurried to the deadline, the film consequently retreated to the familiar in a slapdash attempt to put a bow on a disconnected trilogy; it was later described as “fan service” by co-editor Maryann Brandon (quoted in Sharf 2020). Williams’s score, however, was not so narrow-mindedly focussed on the past. His new themes were among his most emotionally complex and appear to be as much a final addendum to his leitmotivic compendium as a personal goodbye to the career-defining franchise. Even so, his ultimate Star Wars score was marred not only by the overall incoherence of the trilogy but by a chaotic post-production (see Sharf 2020). Entire cues went unused, old cues were recycled and rearranged, and a dense sound mix occasionally made music inaudible. Indeed, reports of a lengthy eleven-day recording have led to much speculation regarding revision (see Burlingame 2019). By comparison, the score as presented in the film is a striking departure from The Last Jedi, which left Williams’s original music largely untouched. We might then regard the music of The Rise of Skywalker as representing the intentions of directors, editors, and music supervisors better than those of Williams himself. In this light, the retrospective aesthetic of the score is unsurprising given contemporary Hollywood’s tendency to rely on the established and the familiar. With this broader context and these industrial tendencies in mind, Jerome de Groot’s definition of nostalgia as an “an empty trope within an overly mediated society” (2008, 249) seems most pertinent. The following examples will reveal the accuracy of this definition.

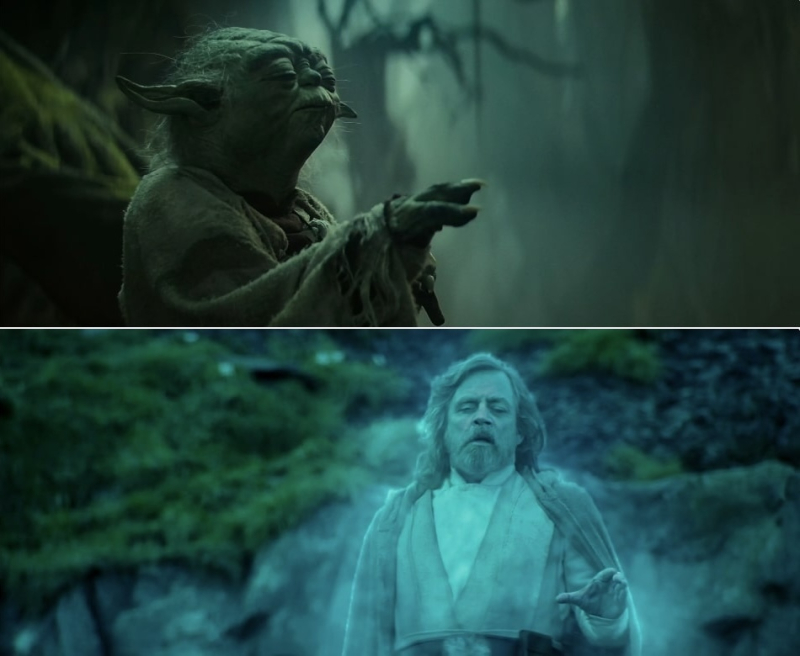

While I do not wish to condemn Williams for the heavy-handed work of others, he is not entirely without fault. A clear instance of his involvement in clumsy sentimentalizing procedures is in the sequence where the ghost of Luke uses the Force to raise his X-wing out of the water, a moment which pastiches Yoda’s identical feat in The Empire Strikes Back (Figure 3). Rather than composing new material or citing appropriate leitmotifs for Luke or the Force, The Empire Strikes Back cue “Yoda Raises the Ship” was re-recorded and inserted into The Rise of Skywalker. Williams detailed the path that led to this instance of reuse in a behind the scenes featurette for the film:

Yoda lifts [the X-wing] in The Empire Strikes Back. Ramiro Belgardt, the music editor, he said “Oh, it should be exactly the music that we had for Yoda!” And actually, J. J. [Abrams] questioned it, he said “Should we? Are we doing that right?” And everybody said “Oh yes. It has to be. The fans will all know.” So we went back to the score for The Empire Strikes Back to get those bars exactly... That actual central piece, of taking the ship up, is exactly as we had it before. It’s an exception: the use of something literal from an earlier film. We’re revisiting specific themes. You know, I’m happy to do it. It’s great to see [this] character revisited here. (Williams in Abrams 2019)

Figure 3

Yoda and Luke lifting the X-Wings: The Empire Strikes Back, Yoda uses the Force to raise Luke’s X-Wing from the water (above); The Rise of Skywalker, Luke uses the Force to raise his X-Wing for Rey (below).

© Lucasfilm; Disney Global Content Sales and Distribution

For Williams, the thematic revisiting of Yoda (who does not appear in The Rise of Skywalker) was an exciting opportunity, a well-intended musical homage. Indeed, some reviewers did respond positively to the reuse: Johnathan Broxton (2019) called it a “wonderful callback” and Christian Clemmensen (2020) encourages us to “excuse such sentimental usage” and to remember that “mass audiences” do not expect innovation but just “want to be reminded of better times”. These positive and forgiving outlooks were not shared by all, however. The film music critic and analyst Sideways explored this reuse in some detail in his YouTube video “Why the Music in The Rise of Skywalker Felt Misleading” (2020). On this scene, Sideways characterized this recycling as a “misuse” of Yoda’s theme, one which “dilute[d its] original meaning”. While the YouTuber’s main argument is that “thematic recontextualization” taints leitmotivic associativity, he also observes that the theme “isn’t telling us anything about the story that we need to know. It’s just referencing an older movie.” Here, Sideways pinpoints a primary issue with regards to thematic recall in The Rise of Skywalker: this is recall for recall’s sake, a symptom of the nostalgiaphilia of Hollywood blockbusters16.

Such was the extent of post-production manipulation and the tendency to cite the musical past that Williams’s level of involvement in another instance of musical reminiscence is less clear. Following the climactic battle and as friends are reunited and celebration begins, listeners were treated to a plethora of warm string-centred themes, a cliché of film climaxes that often indicates “self-conscious mythologization” (Buhler 2000, 44). The cue, “Reunion”, highlights the new “Friendship” theme but also, somewhat strangely, foregrounds two themes which have little semantic pertinence: “Yoda” and “Luke & Leia”. If the short suite of old and new themes reflected Williams’s own reminiscences on the series as a whole, one might forgive the privileging of affect over association17. However, the returning themes in The Rise of Skywalker sound as if they are lifted wholesale from other sources, and almost seem to abruptly cut from one to the other. The statement of “Yoda” is taken from the concert arrangement of his theme and “Luke & Leia” sounds strikingly similar to the “The Spark”. Consequently, the music as used in the scene might represent the work of the editors better than that of the composer. For Nicholas Kmet (2017), such practices and their results can represent something of a structural imbalance. Kmet notes that editors frequently service the “micro-level structures”: the pacing and timing of a scene or the tempo and flow of the music. Their alterations little benefit the “macro-level structures”: the grander narrative mood or the connectivity of leitmotifs across the narrative. With such concepts in mind, we might observe that it is not only musical mood and cue specificity that is affected in The Rise of Skywalker but, also, Williams grander intentions for this film and by extension—considering the significance of this climactic scene—the saga.

These direct reiterations and the extent of the apparent structural imbalance hint at the complications Williams faced in crafting his final Star Wars score. It is not difficult to theorize how an uninhibited Williams score might have impacted the film. Take “Luke & Leia” as an example. There is a noticeable affective discrepancy between the poignant reminiscence of “Luke & Leia” in The Last Jedi and the emotionally hollow context of its appearance in the “Reunion” scene in The Rise of Skywalker. Here, the theme accompanies a conversation between characters Lando Calrissian and Janna, a pair who are so underdeveloped that their familial connection is only revealed in paratexts. It seems odd that the graceless attempt at connecting two minor characters and the long-awaited reunion of the Skywalker twins are musically linked by markedly similar statements of the same theme. Unlike Sideways, I do not hold “thematic recontextualization” solely responsible for the diminished emotionality of “Reunion”. Rather I contend that the larger issue is one of expedient creative decision-making and the privileging of the “micro” over the “macro” (Kmet 2017). Such editorial strategies of generating nostalgia are expected of those marketing the film, not of those making the film, and are evidently cheaper and less affecting than would be the composer’s own original and unimpeded efforts. While Williams has regularly treaded the tightrope of sentimentality with care, thematic cuing here has teetered into the saccharine.

In contrast to the abovementioned coda, the inclusion of a succession of themes in the climactic battle represents a more narratively logical and original and, thus, more effective moment of musical reminiscence. As swathes of supporting ships arrive to the aid of the Resistance, “Heroic Descending Tetrachords” and both sections of the “Main Theme” are given opportunities to shine18. This recollection of material which had bookended each saga film grants the sequence a mythic momentousness distinct from similar moments of heroism across the series. In particular, it is the annunciatory statement of “Heroic Descending Tetrachords” that builds a tangible sense of excitement. Familiar but little used in the narrative, “Heroic Descending Tetrachords” is an incidental motif, a characterization which indicates a “lack [of] substantial development or symbolism” (Lehman 2023). While not as obscure as “Luke & Leia”, like the siblings’ motif, its affective power derives from absence. Given that the incidental motif here appears within the narrative—previously it was mostly known as a component of the closing credits—and in such a marked fashion, lends it a degree of significance which generates a certain reflective quality not unlike a reminiscence motif. In this context, “Heroic Descending Tetrachords” is recognized not in the manner of a distant memory recalled but perhaps as the arrival of something long-awaited or as the fulfilment of some unspoken promise. It is our combination of awareness and surprise that makes the unexpected appearance of the motif rewarding and surprisingly affecting. While it might induce nostalgic feelings, the intention behind the motif seems first and foremost to be geared toward accenting triumph and heralding victory.

“It’s an exception: the use of something literal from an earlier film.” Williams’s words regarding the reuse of “Yoda Lifts the X-Wing” were likely spoken before the film was completed. Instead of the exception proving the rule, it seems that the exception almost became the rule in The Rise of Skywalker. Additional proof includes the delicate “Darth Vader’s Death” from Return of the Jedi, strangely replayed when Rey enters the collapsed Death Star throne room, and the bombastic Holst-redolent chords of “The Last Battle” in A New Hope, which fleetingly sound as the Falcon reaches safety in the opening chase sequence. Such instances demonstrate an increasing disregard for Williams’s music both within this film and the wider series, post-productions’ repeated meddling in the digital age of Hollywood, and the privileging of immediate affect over semantic consistency and long-form musical storytelling. The extent of recycled music in The Rise of Skywalker reveals the sad status of Williams’s music at Disney. Rather than the composer’s newest music being given opportunities to form independent associations and to enter the ear of the audience unaffected, his scores have become—like props, lines of dialogue, settings, and iconography—a device to remind us of the familiar and to reinforce that which Star Wars already is.

Conclusion

Evidently, just as the “exuberant recycling of familiar tropes” grounded the original Star Wars in nostalgia (Midgette 2019), a similar nostalgia for the original trilogy has defined the sequel trilogy. The extra-textual allusions to certain genres and the sounds of classical Hollywood that shaped Lucas’s preceding films have been veritably exchanged for intra-textual callbacks and musical citations. Consequently the references of Star Wars (both visual and musical) have become increasingly insular. Instead of evolving, the sequels were often more concerned with narrative history19. While their reflective nostalgia can effect powerful emotional responses, constant recall can also diminish the scope of the Star Wars galaxy. To borrow Jameson’s description of nostalgia films, “the tone and style of a whole epoch becomes, in effect, the central character, the actant” (1991, 19). In the case of the sequels and their music, this statement remains true; however, now the central character and actant is Star Wars itself.

It is worth noting that this nostalgia is selective and is rarely directed at the prequel trilogy. Perhaps given the collective and critical disdain for them, Williams’s music for these films was rarely resummoned20. Indeed, of his around twenty leitmotifs written for the prequels, Lehman (2023) only counts the appearance of three in the sequels: “Duel of the Fates (Ostinato)”, “Mystery”, and “Battle of the Heroes A-Section”. None of these are so obvious or prominent to reveal any nostalgic intent behind their deployment. Furthermore, a potentially prominent use of “Duel of the Fates” seems to have been cut from The Rise of Skywalker altogether—recorded as cue 8m17, but not appearing in the film or soundtrack releases (see cue list in Lehman 2023)21. Clearly, it was only the sounds of the esteemed and increasingly idealized original trilogy that were worth reviving.

This parochialism has been addressed by John Powell, composer of Solo: A Star Wars Story. When justifying thematic recall in his track “Reminiscence Therapy”, Powell specified that particular sequences “were so reminiscent to me of scenes from the original Star Wars that I always wanted to use that music because it echoed” (Powell, quoted in Kaufman 2018). Such echoes are often the root cause of thematic recall, representing obvious instances in which the new is beholden to the past. Indeed for Abrams, a “legacy film auteur”, this adherence to the familiar and “stylistic emulation” is a veritable trademark (Golding 2019, 83–88). As already noted, visual parallels or plot similarities might not simply warrant the replaying of familiar themes and cues but necessitate it. For Powell, it was the visual familiarity of a chase sequence in Solo that required the revival of familiar themes (“Rebels” and “Death Star”) and set-piece cues (“Here They Come” of A New Hope and “The Asteroid Field” of The Empire Strikes Back). He framed his citations by contextualizing reminiscence therapy, noting it as

a medical term for a method that helps patients who have dementia, reminding them what their lives were. Family members and friends would pitch in, collecting photos, videos, stories, the music they loved and experiences they had with that person into an album of the memories of their life… In certain instances it can bring people back. (Powell, quoted in Sun 2018)

Powell’s title and his evident desire to “remind” audiences through reference indicate his understanding of the latent affective capabilities of Williams’s existing Star Wars music, as well as the wider “restorative” aesthetic of Disney’s Star Wars (Boym 2001, xviii). Rather than merely echo the familiar, many instances of reminiscence therapy in the sequel trilogy compound visual and narrative nostalgia, revealing the filmmakers’ ultimate desire to “bring people back.”

As some of the aforementioned reviews and my own evident stance on certain callbacks might have indicated, the effectiveness of musical reminiscence therapy may vary from fan to fan and depend on their preconceived expectations of, and desires for, modern Star Wars films. For some, the rearranging of the familiar in a context which resummons the stories of the past might assuage fears and trepidations. For others, the musical recycling might appear as a conceited effort to make the unfamiliar more palatable. Regardless of one’s personal inclinations, it cannot be denied that nostalgia has become endemic in Disney’s Star Wars and that the sequels and spin-off films (like Solo) have used musical citations like a “tranquilizer” to disquiet anxieties and to dissolve temporal dialectics (Boym 2001, 33)22. However, these attempts to reassure instead only reveal an often creatively impoverished present, further distancing us from that always already lost historical utopia.

Rather than simply evoking the past, reminiscence motifs and reminiscence therapy highlight our distance from it. With the sequel trilogy’s frequent attempts to return and restore through recollection, Powell’s previously mentioned metaphor of the “echo” proves increasingly apt. Each successive repetition of a motif or cue—whether by the original composer, a devotee, or a music editor—appears to wane in terms of affective power. An echo cannot be a clone and will always diminish in strength until it becomes nothing more than a whisper. In the case of the sequels, Williams’s scores demonstrate that these nostalgic echoes can occasionally resonate with filmgoers returning to the galaxy far, far away but more often they seem to reveal a lack of autonomy and an overwhelming tendency toward self-mythologization. What was once the careful savouring of a leitmotif, the poignant recall of a reminiscence motif, or the occasional recycling of a cue became something altogether more rampant, unwieldy, and ineffective as the trilogy attempted to progress. The result was an aesthetic which tarnished both Williams’s autonomy and the musical integrity of the Star Wars sequels, a trilogy unable to let go of everything it feared to lose.