“If there was one single musical form synonymous with the Empire it was the march.”

(Richards 2001, 41)

Although Jeffrey Richards’s book Imperialism and Music. Britain 1876–1953 studies music’s role in the British Empire, the Galactic Empire, at the center of the Star Wars universe, also reflects many of the book’s claims about both musical styles and the function of music within society. This connection is nowhere more evident than in the central role marches play in the soundscape of both Empires. The British Empire has its fair share of marches, from Charles Hubert Hastings Parry’s early examples to Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance (1901–1930) and William Walton’s Crown Imperial (1937). The Galactic Empire, too, is represented by one of the most recognizable marches ever written: John Williams’s “Imperial March” (Clip 1). Beginning with the release of The Empire Strikes Back in 1980, this theme has become inextricably linked with images of Imperial troops, star destroyers, and its most iconic representative, Sith Lord Darth Vader. Although the “Imperial March” and the British imperialist idiom seem on the surface to be very different, they share deep musical resonances that fortify connections between the two empires.

For his Star Wars scores, Williams leans particularly heavily on the film music staples of romanticism and leitmotivic scoring for a specific reason: to give the score a “familiar emotional ring” that normalizes the aliens and unfamiliar locations of the films (Cooke 2008, 463)1. Williams’s score for The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) is demonstrative of his neo-Romantic leitmotivic approach to film scoring: Williams uses several themes from A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977), in addition to the new ones. The “Imperial March” is one of those new themes. Williams did write a motif for Darth Vader in A New Hope, using “bassoons and muted trombones and other sorts of low sounds,” but Vader’s increased presence in The Empire Strikes Back—along with the augmented threat of the Empire as a whole—prompted Williams to create a new and more prominent motif for the villains (Matessino 1996a, 12–13). The newly-composed “Imperial March” is not only a more robust theme in comparison to the imperial motifs in A New Hope, but it quickly became one of the most recognizable themes in film music and, according to music theorist Frank Lehman’s calculations, the second most used leitmotif in the Skywalker saga (Lehman 2023, 100). Due to the status of the “Imperial March” as a leitmotif, some instinctual perceptions that the Empire is evil come from an intrinsic awareness of what the “Imperial March” implies with its minor mode, chromaticism, and nefarious orchestration in the low brass and strings2. Williams discussed the necessity of creating a new theme for the Imperials in The Empire Strikes Back in multiple interviews leading up to the film’s premiere. In one interview, Williams noted that the theme should be “majestic… and it should be a little bit nasty,” suggesting music that is both villainous and dignified (quoted in Lehman 2019).

Part of creating meaning in music, whether using leitmotifs or not, is through music’s referentiality and how it relates to the music that came before it. This prompts the question: where does the “Imperial March” originate from that enables it to obtain those “majestic” and “nasty” qualities? The title of the concert arrangement, “The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme),” provides some hints of its origin. Williams automatically creates associations with other fictional and real empires by naming his theme the “Imperial March.” In listing “Darth Vader’s Theme” in parentheses rather than as the main title, Williams signals that he conceived the leitmotif to represent the Empire as a whole first, and only represents Darth Vader as an agent of the government. Given Williams’s self-proclaimed love of British music, expanded upon later in this article, perhaps the title is also a subtle allusion to the British Empire. This article, then, asks how the theme’s musical content relates to this British musical style and what those connections add to the theme’s accumulated meaning.

Musical connections come in many forms, from allusions to full quotations. As Jeremy Orosz writes, “No music is composed in a vacuum. All music is intertextual; virtually any piece includes moments that remind us of another musical work” (Orosz 2015, 299). Since many composers learn how to write music by imitating other composers, it is unsurprising that music is so interconnected with its historical precursors. Adding in the prevalence of temp tracking in films, it is no wonder film scores get compared to other pieces of music frequently. Because composers are often asked to imitate the preexisting music that the director inserted during the editing process, film music frequently bears more than a passing resemblance to other pieces. The “Imperial March” specifically demonstrates what V. A. Howard, in a general theory of musical quotation, describes as non-quotational allusion: it does not explicitly quote any particular piece of music but instead alludes to several genres and styles (Howard 1974, 309).

Although Williams has never explicitly stated any direct references or inspirations for the theme, his allusions in the “Imperial March” are vast: minor-mode funeral marches like those of Frédéric Chopin or Gustav Mahler, chromatic and sardonic marches of composers such as Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich, and most significantly, other imperial marches, particularly those of British composers like Edward Elgar. These references—and many others—help Williams portray the evil Empire musically and create a connection between not just the composer and the audience but also between the film world and the audience. In the first section, I explore previously suggested inspirations for the theme, concluding with the suggestion of Elgar’s First Symphony (1908) as an additional reference point and an exploration of Williams’s Anglophilia more generally. In the second section, I delve into two diegetic versions of the “Imperial March”—in Star Wars: Rebels (Disney XD, 2014–2018) and Solo: A Star Wars Story (Ron Howard, 2018)—and how they further the connections between the original theme and two real-world imperial forces: Nazi Germany and the British Empire. Finally, I investigate the similarities between the British and Galactic Empires.

“I am your father”: Speculated Origins of the “Imperial March”

Commentators have postulated several pieces and styles of music as possible sources of the “Imperial March.” In this section, I investigate previously suggested inspirations for the theme, highlighting the aspects that may have been on Williams’s mind while writing the march in 1979. None of these pieces is a direct model for the march, which does not feature any direct quotations of its precursors. Additionally, it must be noted that many of the elements Williams borrowed from the marches were likely not meant as allusions to any individual piece, but rather those musical elements that are standardized in marches more generally.

The composers most frequently cited as possible sources for the “Imperial March” are Russian: Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Sergei Prokofiev, and Dmitri Shostakovich3. Mervyn Cooke identifies the finale of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (1876) as a piece that “inhabits the soundworld” of the “Imperial March,” noting that Williams frequently invokes Tchaikovsky’s ballet music (Cooke 2008, 463)4. The most prominent similarity is the texture in the final scene, perhaps what Cooke meant in using the term “soundworld” (Clip 2). The brass-heavy texture, especially the low brass emphasis, produces a similar sound to some of the heavier and slower renditions of the “Imperial March,” like in the Battle of Hoth sequence in The Empire Strikes Back. The theme itself, associated primarily with the villain Rothbart throughout the ballet, creates an immediate association with villainy. Harmonically, minor and diminished chords support the return of the main theme of the ballet, and the excerpt even includes a i to ♭vi progression (spelled enharmonically) in B minor. Beyond the texture and brief harmonic progression, however, the similarities remain limited.

The proposed Prokofiev connection may be stronger than that with Tchaikovsky. Williams frequently evokes Prokofiev’s “angular melodies and enlivenment of solid tonal harmonies with acerbic added dissonances” in his own music (Cooke 2008, 463)5. The piece that may have inspired Williams’s “Imperial March” specifically is the “Dance of the Knights” from Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet (1938). In the brief B section of the dance, a melody appears in the low brass that begins with three repeated notes (Clip 3), prompting one brass section to prank their conductor in rehearsal and replace Prokofiev’s melody with Williams’s6. The static harmony of this moment, F minor, combined with the three repeated melodic notes at the beginning of the phrase, allows for the superimposition of the “Imperial March” melody over Prokofiev’s accompaniment. Because the first four measures of the “Imperial March” are predominantly one chord, the theme fits nicely over an F minor pedal once transposed down a whole step. Despite its ability to support the “Imperial March” melody, a static minor harmony and three repeated notes are hardly enough to argue that this brief excerpt is the main inspiration for the “Imperial March.”

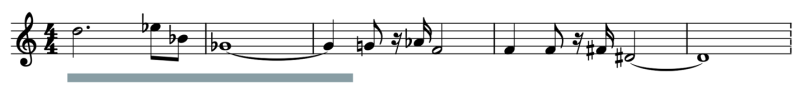

Shostakovich is another frequently-discussed influence on Williams. Two aspects of Shostakovich’s style are possible reference points for Williams with the “Imperial March”: his preference for heavy brass and percussion and the Shostakovich staple of the sardonic march. An example of this type of march is the second movement of the Eighth Symphony (1943), a chromatic and “nasty” march, if not a particularly “majestic” one—although the connections between this march and Williams’s do not extend beyond the orchestration (especially the moments with heavy brass) and the use of chromaticism. Perhaps a better Shostakovichian model for the “Imperial March” comes from the opening theme of his First Symphony (1926; Figure 1a). This theme bears striking similarities to the second half of the presentation phrase of the “Imperial March” (Figure 1c): the themes have almost identical contours and intervallic content. Although the first iteration of the theme in Shostakovich’s symphony is not an explicit march, later iterations place it in a march context, furthering the connections with Williams’s march. An additional similarity with Shostakovich’s symphony appears in the second movement, where a theme begins with three repeated notes and, like the example from the first movement, has an identical contour to Williams’s march (Figure 1b). Also similar to the first movement, this theme is initially introduced quietly in the winds but it gains more powerful—even martial—iterations later in the movement. In a sense, the combination of these two themes produces the building blocks of Williams’s presentation phrase. These two brief moments in this symphony are perhaps the most plausible origin for the “Imperial March” thus far.

Figure 1a

Symphony no. 1 in F minor (Dmitri Shostakovich), trumpet solo from I. Allegretto – Allegro non troppo (mm. 1–5), author’s transcription.

Figure 1b

Symphony no. 1 in F minor (Dmitri Shostakovich), flute theme from II. Allegro (5 before 7 – 5 after 7), author’s transcription.

Figure 1c

“The Imperial March,” presentation phrase (mm. 1–4), author’s transcription.

The most frequently cited non-Russian composers as possible inspirations for the “Imperial March” are Richard Wagner and Gustav Holst. In the case of Wagner, this influence comes from his so-called “Tarnhelm progression,” first used in the Ring Cycle (1869–1876), which music theorist Matthew Bribitzer-Stull explains as two minor triads whose roots lie a major third apart (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 132). The “Tarnhelm” progression came to have many connotations as composers began using it more frequently, particularly in film where it frequently represents villains—“the sinister, the eerie, and the eldritch” (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 155). This reference may have more to do with the relative ubiquity of this particular progression in a post-Wagner music scene—any similarities are more likely a result of film music’s adoption of Wagnerian practices—than a specific reference to Wagner on Williams’s part. Turning to Holst, the primary cited inspiration is “Mars: The Bringer of War,” the first movement of The Planets (1918)7. The movement features some elements that are also present in Williams’s “Imperial March”—a strongly rhythmic ostinato (including the use of triplets) played by the strings through much of the movement and heavy brass and percussion. Beyond these surface-level similarities, there is little in the movement to suggest much of an influence8. Like the Russian composers, the influence of Wagner and Holst does not seem to tell the whole story.

More frequently than any single composer or piece, the funeral march as a genre is frequently mentioned as Williams’s main inspiration. Among the plethora of funeral marches, the most commonly cited is the second movement of Frédéric Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 35 (1839). Several aspects of Chopin’s march relate to Williams’s march. The first of these connections is the melodic line—Chopin begins with several repeated notes. The frequently descending melodic contour is another shared aspect of the two marches, as is the use of the dotted eighth-sixteenth note rhythm. Since the descending contour and the dotted rhythm are both commonly associated with funeral marches (Burke 1991, 44), Williams was likely not referencing any specific piece with those two elements. The most profound connection comes in the harmony: for the first fourteen bars of Chopin’s funeral march, he alternates between two chords—B-flat minor and G-flat major in second inversion. Williams plays with a similar harmonic oscillation, going from the tonic to scale degree six, but uses the minor instead of the major submediant. Even if Chopin was not a direct influence, subsequent orchestrated funeral marches—most notably those frequent in Mahler’s symphonies—point to the style being a prominent and continuing musical reference into the twentieth century.

Each of these musical examples contains similarities to Williams’s “Imperial March,” but none is a perfect candidate for the march’s origins. In other words, although Williams might have had some (or all) of these pieces and styles in mind while composing the march, none sticks out as being the only direct influence. On the contrary, looking at the inspirations one after the other, it is more likely that Williams picked elements of each and combined them into a jumbled concoction of musical ideas that somehow perfectly encapsulates both the Empire and Darth Vader. Despite the length of this list of possible inspirations, I argue that the British imperialist march provides a previously unnoticed influence—one that has deep significance for understanding potential broader implications of the theme.

British Music and Williams’s Original “Imperial March”

Williams himself notes his love of British music in one interview: “I’ve always been a lover of Elgar and [Ralph] Vaughan Williams and William Walton… I admire the great musical tradition in this country, so I suppose you could say I’m an Anglophile” (quoted in Sweeting 2005). In addition, he implies a connection to the British idiom in the “Imperial March” in another interview. In discussing the various aspects of the march—the minor mode, the strong melody, the militaristic features—he suggests that the combination of these aspects results in “this kind of military, ceremonial march” (quoted in Byrd 1997, 240). His use of the word “ceremonial” here cannot help but conjure up images of the British Empire. Historian Chris Kempshall also notes this aspect of the “Imperial March” and its connections to the British repertoire, claiming it draws on “Grand Imperial Marches” (Kempshall 2023, 30). The casting of British actors for the Imperial officers furthers the connection between the two Empires, making the musical link all the more fitting.

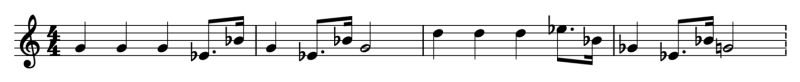

With his self-proclaimed Anglophilia in mind, then, perhaps it is worthwhile to explore this repertoire as a possible influence on the “Imperial March” specifically. The influence of the British musical idiom—and the most plausible British inspiration for the theme—comes in the march theme from the second movement of Elgar’s First Symphony (Figure 2 / Clip 4). This comparatively brief march fits Williams’s “Imperial March” goal of writing a “nasty” and “majestic” march.

Figure 2

Symphony no. 1 in A flat (Edward Elgar), II. Allegro molto (mm. 42–49).

The theme itself is strikingly similar to Williams’s march. Both melodies begin with three repeated quarter notes followed by a dotted eighth and sixteenth and display an overall descending trajectory. The last measure of the Elgar has a rhythmic reversal of a prominent rhythm in Williams’s march: an eighth note followed by two sixteenths. The theme appears in three large sections, two of which feature several iterations of the theme. The first begins in C-sharp minor with a version transposed up a whole step a few measures later to D-sharp minor. The second section is very similar to the first—in F-sharp minor and G-sharp minor—but resembles Williams’s march even more closely due to the orchestration. In this section, the violins, flutes, and piccolo play a series of ascending scales over the melody that begin and end on F-sharp—the mediant of the local key of D-sharp minor. This emphasis on the third scale degree suggests an alternative explanation for the chordal submediant emphasis in Williams’s theme. In the last iteration of the theme, the use of low winds (bass clarinet, bassoon, and contrabassoon) and low brass (trombones and tuba) creates a more violent version of the march theme. To end this section, Elgar extracts just the descending dotted phrase over a series of sixteenth notes and triplets—all aspects present in Williams’s “Imperial March.” The final march section, similar to the middle section of Williams’s march, features an augmented rendition of the theme—a written-out half-tempo version—in F-sharp minor.

In this movement, the melody, rhythm, and orchestration of Elgar’s march all bear unmistakable similarities to Williams’s “Imperial March” making the march theme a credible Elgarian source of the “Imperial March.” To add to the already strong resemblance to Williams’s theme, Elgar’s march is surrounded by chromaticism that is reflected in the chromaticism of the “Imperial March.” Although the explicitly imperial connection is missing in Elgar’s symphony—it is, after all, supposed to be a piece of absolute music—any listener who knows anything about Elgar cannot help but remember the importance of the imperialist style to Elgar’s oeuvre more generally, especially given the more ceremonial march theme in the previous movement. Any Elgarian march, then, whether ceremonial or not, is bound to have some imperialist implications in listeners’ minds.

Williams’s Anglophilia and The English Musical Renaissance

With a possible musical link between British music and the “Imperial March” now established, it is worth exploring the probability of Elgar being a reference point for Williams. But first, I would like to look briefly at the evolution of British music around the turn of the twentieth century to contextualize Williams’s references to that style. The origins of the English style resulted from a rise in nationalism in the arts and criticism that the English were not genetically capable of writing—or playing—“great” music (Crump 1986, 166 and Porter 2006, 143). Since around 1900, the term often used to describe the resultant resurgence of British music is the “English Musical Renaissance” (Caldwell 1999, 258). Composers began to turn to music that was overtly English and “clearly projected aspects of national character”—incorporating various styles, including folk song, Celtic music, and church music. This period of nationalization of music, beginning in the 1880s, coincided with the highest point of the British Empire, lending the music not only a national identity but also an imperial one (Frogley 1997, 151 and Richards 2001, 9–14). Three generations of composers provide a convenient window into this tradition and how it evolved: Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, Edward Elgar, and William Walton.

Lewis Foreman dates the English Musical Renaissance to the 1880 premiere of Hubert Parry’s Prometheus Unbound (Foreman 1994, 6). One of Parry’s most significant contributions to the national character in music was his use of popular forms, including the march. His marches laid the foundation for later ones, including those of Elgar. His “Bridal March” from the incidental music for the Greek play The Birds (1882) provides just one example of a proto-Elgarian march. Bernard Benoliel proposes that Elgar “absorbed Parry’s style more successfully than any other English composer and transformed it into a personal, multi-faceted medium of expression” (Benoliel 1997, 115). Elgar, in historian David Cannadine’s view, elevated the ceremonial march style “from mere trivial ephemera to works of art in their own right” (Cannadine 2012 [1983], 136). Elgar’s first high-profile march was the Imperial March, written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. From the Coronation Ode (1902) on, the patriotic style that Elgar developed was inextricably linked with royal rituals and the pageantry associated with them.

Perhaps the most direct link between the British national style and the music of John Williams is the composer William Walton. Walton himself was influenced by Elgar, evident in his coronation marches. Walton’s take on Elgar’s imperial idiom may explain how Williams came across this material. Williams conducted Walton’s Crown Imperial with the Boston Pops twice in 1987 and Orb and Sceptre five times in 1979 and 19809. The fact that he was conducting Orb and Sceptre around the time of composing The Empire Strikes Back could explain the Waltonian influences in the score and possibly the connection between the “Imperial March” and the British idiom. Walton also transplanted this coronation march idiom into his own film scores. One score that may have been particularly influential for Williams was Battle of Britain (Guy Hamilton, 1969). While Williams was in England for the casting process of Fiddler on the Roof (Norman Jewison, 1971), he was invited to visit Walton’s recording sessions for Battle of Britain at the Anvil Film and Recording Group scoring stage on April 21, 1969 (Matessino 2021, 15). Here is definitive proof that Williams was familiar with at least some of Walton’s film music—although Walton’s full score is lost and Michael Matessino does not indicate which section of the score Williams heard when he visited the scoring session. The score, of which about 21 minutes and a suite remain, sounds like a descendant of Elgar’s music10.

Williams, however, does not credit just that one recording session for his love of British music. In addition to the interview with the composer himself quoted above, Williams also cites Walton as “a great favorite of mine” (quoted in Lace 1998). Mervyn Cooke also suggests Williams’s appreciation for Elgar, noting Williams’s many British musical references in his other film scores (Cooke 2018, 13–14)11. Clearly, Williams is familiar with this repertoire—and has great affection for it—suggesting that the musical connections between his music and the music of British composers are even more plausible12.

British influences in John Williams’s music are not hard to find, but discussions of British musical influences in Star Wars frequently note only the “Throne Room” cue from A New Hope, along with the occasional mention of a Waltonian section of the Hoth battle sequence and the music for Cloud City and Lando Calrissian, both from The Empire Strikes Back. For the “Throne Room” cue, Williams explicitly acknowledges this influence. In the liner notes for A New Hope, Williams writes: “I used a theme I am very fond of over the presentation of the medals. It has a kind of Land of Hope and Glory feeling to it, almost like coronation music” (quoted in Matessino 1996b, 27). Indeed, Elgar’s style is evident in this cue: a mobile bassline, simple ternary form, a memorable, nobilmente-style melody, and his distinctive three-part texture are all present. The melody also bears striking similarities, not to a specific Elgarian model, but a Waltonian one: Walton’s Orb and Sceptre (1953), a piece Williams himself conducted on multiple occasions.

Diegetic Versions of the Imperial March and The Elaboration of the British Connection

Two renditions of the “Imperial March” by composers other than Williams confirm the stylistic reference point of British music, and one even takes it a step further. These two versions represent two of the most radical transformations of the theme in Star Wars. Rather than simply changing tempo, orchestration, or key, these versions reinterpret the original minor-mode theme in a major key. In doing so, they augment the relationship between Williams’s theme and the style of march championed by composers like Edward Elgar and William Walton.

The first of these major-mode versions of the “Imperial March,” however, suggests a different stylistic reference: Nazi propaganda marches. This cue is “Glory of the Empire,” written by David Glen Russell for Star Wars: Rebels Season 1, Episode 8 in 2014 for an Imperial parade (05:59, Clip 5). Series head composer Kevin Kiner assigned the cue to Russell, who quickly set about finding a way to re-work the leitmotif with a “major and upbeat” twist that “is counter to the original use of the ‘Imperial March’ and counter to the darkness of the Empire.” He modeled his version on military marching band music, specifically 1940s newsreels, that “[wouldn’t] sound like a big post-Romantic orchestra but more like a small group of musicians assembled on Lothal just for the parade” (Russell 2022). In adapting the theme, Russell wanted to make the least number of changes possible to obtain his desired effect. Importantly, he maintains the melody of the “Imperial March,” untransposed, while changing the rhythm, harmony, and orchestration. Harmonically, he mostly keeps the changes to the modal shift from minor to major—though he fills in some of the harmonies in the continuation phrase of the theme. Russell also plays with the orchestration, allowing the piece to sound like a band on Lothal. He reduces the orchestration, mainly featuring brass instruments and eliminating the ostinato in the process13. To compensate for the lack of rhythmic drive, he adds double and triple tonguing into the trumpets to mimic the ostinato rhythm and bring more energy—and consequently a more upbeat feeling—to the theme. These changes, according to Russell, were motivated by the diegetic nature of the cue—mimicking a small “military band on an outer rim planet.”14 Although this militaristic march style applies to many marches in many different nations, Russell was specifically aiming to evoke Nazi newsreel footage, drawing parallels between the Third Reich and the Galactic Empire.

While Russell’s cue recalls the inspiration of Nazi Germany in George Lucas’s initial vision for Star Wars, John Powell in his cue “Imperial March – Edwardian Style” (Solo: A Star Wars Story, 12:59), reworks Williams’s theme in a more British style (Clip 6). Powell added the cue as a “last-minute gag”—the cue was requested, composed, and performed during a single day of the recording session (Star Wars News Net 2021). Notably, Powell openly admitted to wanting to evoke Elgar in this cue: “Knowing that John Williams is a big fan of Elgar and that everyone says that that particular tune comes from here and here and here, and a bunch of Russians. And then… I thought, well I wonder if that could be made into his other love… which is Elgar” (Star Wars News Net 2021).

Unlike Russell, Powell allowed himself more liberties with Williams’s original theme and significantly changed the melody. He retained the melody in the first two measures but then veers off and rewrites most of the theme, maintaining the contour to keep it recognizable. Many of Powell’s melodic changes directly result from his harmonic choices. He noted that the opening two measures of the original melody outline an E-flat major chord and took this as a hint to reharmonize the entire theme in E-flat major—a key with no small significance in British imperialist music. Elgar himself viewed this key as being “warm and joyous with a grave and radiating serenity” and made frequent use of the key (Adams 2007, 81–83). In Powell’s “Imperial March,” the key certainly contributes to making Williams’s sinister melody more “warm and joyous,” though the tempo and jauntiness of the rhythm do somewhat mask the “grave and radiating serenity” that Elgar describes in his characterization of E-flat major. Missing in Powell’s arrangement, however, is the relationship between G and E-flat as alternating chords throughout the theme; instead, Powell opts for the plagally-oriented A-flat to E-flat motion, creating another link to Elgar’s musical style. Due to some of the changes Powell made to the theme, his version features the greatest variety of chord qualities and chordal inversions, a result of his mobile bassline. The importation of this imperial style into Williams’s theme serves as a reminder of Williams’s own love of British music.

British References in Powell’s “Imperial March”

To fully understand Elgar and Walton’s impact on Powell’s arrangement, however, it is vital to understand how this lineage of British composers developed and influenced each other. I will now highlight how each of the three main English Musical Renaissance composers contributed to the development of the musical style that Powell draws on for this cue. To do so, I will trace three important aspects of the British imperial march style—harmony, orchestration, and texture—and how they were passed down between the three generations of composers to Powell’s arrangement of the “Imperial March.”

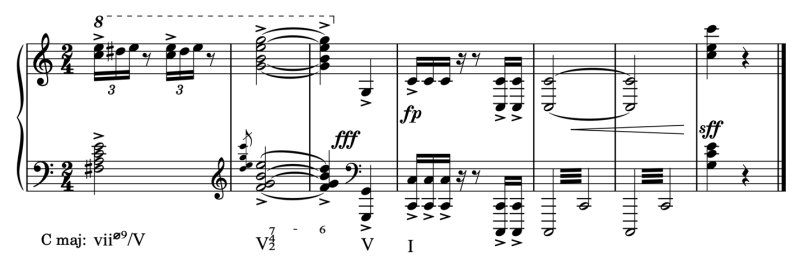

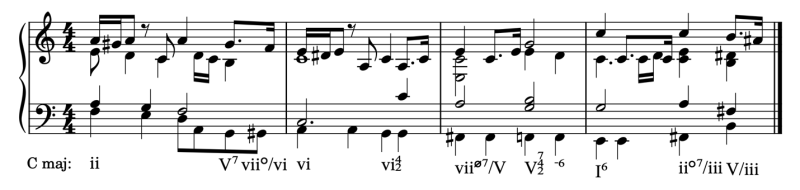

Like in many musical styles in the West, harmony is one of British music’s most complex elements and is difficult to generalize. One specific aspect of this harmonic style, however, became important in the English compositional lineage—so much so that Powell incorporates that same harmonic detail in his arrangement of the “Imperial March” as a quintessentially Elgarian progression. That element is the progression from a secondary half-diminished seventh chord (of V) resolving to a dominant seventh chord in third inversion. Vital to this progression is the 7–6 suspension in the dominant seventh chord. Although Powell considered it a quintessentially Elgarian progression, it appeared in English music before Elgar began to use it. Parry’s Symphony No. 2 in F Major “Cambridge” (1883) uses this progression in the first movement (Figure 3a). Moving along the family tree of English composers, Elgar uses the progression at the end of his fifth Pomp and Circumstance march (Figure 3b), and Walton uses it in the opening of his Spitfire Prelude and Fugue (Figure 3c) from the film The First of the Few (Leslie Howard, 1942). In Powell’s reharmonization of the “Imperial March,” this important detail appears in the eighth measure of the theme (Figure 3d). Both the harmony and voice leading of this progression are key components of the British imperialist style, and Powell exploits its ubiquity to explicitly connect his arrangement of the “Imperial March” with this music.

Figure 3a

Cambridge Symphony, 1st Movement (2 after D).

Figure 3b

Pomp and Circumstance no. 5, ending.

Figure 3c

Spitfire Prelude and Fugue, opening.

Figure 3d

Solo: A Star Wars Story, “Imperial March – Edwardian Style” (mm. 6–9), transcription by Frank Lehman.

Another vital element of this style is the orchestration. Although orchestration is frequently ignored in musical analysis, the impact that it has on any given moment of a piece is often substantial. This British march style, for example, is characterized by prominent, warm strings despite its martial character. This feature, like the progression discussed in the previous paragraph, can be traced back to Parry. Take his “Bridal March” from the incidental music for The Birds, for example: the march opens with prominent strings, doubled quietly in the clarinets, bassoons, and horns (Clip 7). The effect of the subtle wind doubling is to add to the warmth of the strings in this passage, the beginning of an English march hallmark. Elgar solidified this orchestration in his own marches to the point that this string texture was more or less obligatory in a British march (Crump 1986, 167 and Cooke 2020, 88). The trio section, in particular, became a space where Elgar highlighted this sound world—for just one example, his first march, the Imperial March of 1897, already features these warm strings (Clip 8). Walton continued this tradition, for example in the trio of his Orb and Sceptre (Clip 9). Like Parry’s march, he subtly uses the clarinet doubling to provide warmth to this section. It is hardly surprising, then, that Powell’s orchestration, done by John Ashton Thomas, also highlights the strings. However, given that this cue was written and recorded in the space of a single day, this orchestration choice may just be a result of the musicians on the recording stage that day. Regardless of the reasoning, the balance is very similar to British marches, particularly the trios15.

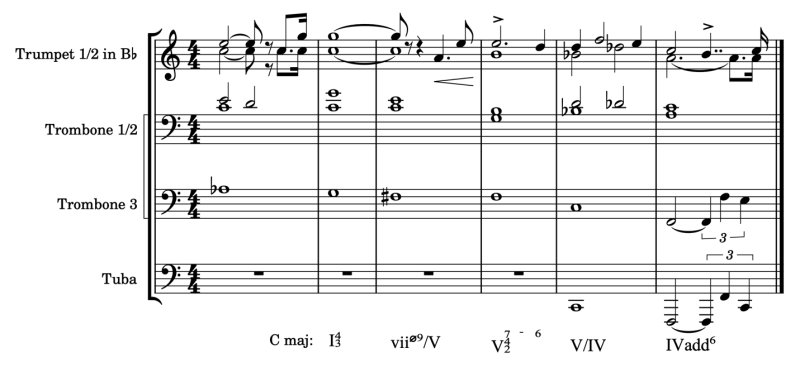

Related to the orchestration is perhaps the most quintessential stylistic marking of English marches: the three-part texture. This texture consists of a melody line, a countermelody (which may or may not be an independent line), and a mobile bassline—the bassline is often highlighted as one of the most vital features of this style. Although Elgar often gets the credit for popularizing this texture—which he undoubtedly did—his use of the technique was once again predated by Parry. Returning once more to the “Bridal March” from The Birds, we can see the melodic line in the first violins and first clarinet, the countermelody in the second violins and violas and doubled in the second clarinet and first bassoon (it is common for this middle voice to have multiple voices doing slightly different patterns), and the bassline in the second bassoon, cellos, and basses.

Moving to Elgar’s version of this texture, we find it in what Jeffrey Richards describes as the “greatest expression” of Elgar’s style (Richards 2001, 67): his First Symphony in A-Flat Major (1908). Looking at the apotheosis of this first march theme at the beginning of the symphony, we can see that despite its expanded orchestration, it retains the three-part texture (Clip 10). The melodic line is played by the upper winds, horns, and first violins, the countermelody is in the English horn, clarinets, second violins, and violas (again, with some differences between the parts), and the mobile bassline is in the bass clarinet, bassoons, tuba, cellos, and basses. Finally coming to Walton’s version of this texture, we see it in the trios of both of his coronation marches—Crown Imperial and Orb and Sceptre. In the latter, Walton places the melody in the first violins (doubled by clarinet), the countermelody in the second violins and viola, and the bassline in the cellos and basses.

Again, it is clear that Powell followed the English example in his version of the “Imperial March.” Powell predictably places the theme in clarinets 1 and 2 and the first violins, the countermelody in the third clarinet, first two bassoons, horns, second violins, and violas, and the bassline in the third bassoon, cellos, and basses. As one of the most identifiable features of the British march style, Powell and Thomas pinpointed both the elements of this three-part texture (melody, countermelody, and bassline) and their typical distribution amongst the instruments of the orchestra. Note how all four marches that I have discussed have the melody in the first violins and some upper winds (most frequently the clarinets), the countermelody in the second violins and violas doubled by (typically) lower winds, and the basslines in the cellos and basses, often supplemented by the bassoons and tuba. In distributing their instrumental forces in this way, Powell and Thomas make a clear reference to the English march style, strengthening the associations provided by the harmony and the general texture.

Looking at this lineage of British composers, Powell’s evocation of the British march idiom is right on target. From the foundations with Parry, to the crystallization of the style by Elgar, and finally the modernization by Walton, each step in the chain added something new while drawing on the composers who came before. Powell fits into this lineage through his integration of the idiom into the “Imperial March.” By drawing on specific elements of the style—particularly the Elgarian progression, orchestration, and three-part texture noted above—Powell successfully fuses an Elgarian-style march and the “Imperial March,” enabling him to achieve the pro-Empire, propagandistic feeling required for a military recruitment commercial while paying homage to one of Williams’s favorite composers. Additionally, the ease with which Powell was able to adopt the theme in an Elgarian style suggests that some stylistic elements were already latent in that original march—elements that are perhaps revealed by the original march’s connections to and similarities with the second movement of Elgar’s First Symphony.

A Tale of Two Empires: The British Empire and the Galactic Empire

The musical connection between music for the Galactic Empire and music for the British Empire does more than suggest an influence on Williams’s “Imperial March,” however; it suggests that there is a more fundamental connection between the two empires. George Lucas drew upon many real-world references in developing the galaxy’s government. Although the main reference for the Galactic Empire was Nazi Germany, other influences include Imperial Rome, the Soviet Union, and the British Empire. Lucas’s combination of these real-world references allows the Galactic Empire to be a unique entity while still enabling viewers to recognize aspects of the system. One connection between these various influences is the importance of nationalism in their music. Ethnomusicologist Philip Bohlman writes that “music is malleable in the service of the nation not because it is a product of national and nationalist ideologies, but rather because musics of all forms and genres can articulate the processes that shape the state” (Bohlman 2004, 12). Nothing inherent to the diegetic versions of the “Imperial March” gives it a nationalistic quality; the melody, rhythm, and harmony do not offer any intrinsic information about the music’s function. But the way the Empire uses the music lends it a nationalist flavor. In other words, the context in which these two cues appear changes the meaning of the music and its associations. The Empire alters the music to fit its current nationalist objectives—in the Rebels parade and Holonet broadcast, the music creates excitement for the celebration of the Empire; in Solo’s recruitment ad, the music aims to make the military seem enticing. Music with an explicitly nationalist purpose also “plays a role in erasing the voices of the nation’s internal others and foreigners. In state rituals, nationalist music… makes no room for alternative and resistive voices” (Bohlman 2004, 20). Instead of hearing two distinct musical styles on Corellia and Lothal, we hear two variations of the same music. They differ in many respects, but the fact that they are the same theme indicates that it is part of an Imperial musical agenda. We do not hear much other diegetic music on these two planets, further suggesting that the Empire came in and silenced indigenous voices.

Looking at the connection that the music suggests, that of British imperialism, helps illuminate aspects of the Galactic Empire that are not fully explained by the oft-cited Nazi connection. Although the Empire does not have any explicitly named “colonies,” film scholar Kevin J. Wetmore remarks that “imperial domination, colonization, and the use of violence to impose order are apparent in all of the films” (Wetmore Jr. 2005, 49). As Edward Said notes in Culture and Imperialism, colonialism is just one aspect of imperialism, which Said defines as “a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory” (Said 1993, 9). Although this definition is not perfect for the imperialism in Star Wars, it gets close to how the Imperial system works: one group of elites controls the vast and expansive galaxy from a single planet. They build military bases and factories on distant planets and maintain a constant military presence on those planets—similar to the administrative colonies of the British Empire. So, although Star Wars does not display overt colonialism, imperialism certainly plays a role in the governing of the Galaxy with a small group maintaining absolute power over many cultures16. As part of their imperialist policies, both Empires control and exploit the resources of the lands they occupy, an element brought to the fore in Disney-era Star Wars. Jedha, in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (Gareth Edwards, 2016), is the clearest example of the Empire’s exploitation. Jedha City is under Imperial occupation—Imperial troops, including an AT-ST and tank, patrol the city as a Star Destroyer hovers overhead. At the same time, the Empire extracts kyber crystals from the planet, stripping the ancient holy city of its primary natural resource. We also see this exploitation in other locations—the Empire’s use of Lothal’s citizens in its factory in Star Wars: Rebels, for example. The connection between the British and Galactic Empires is apparent in both how the governments control vast territories and in their exploitation of resources.

Like many totalitarian regimes, one common feature in these two Empires is the use of propaganda to control their populations, and one method of spreading these propagandistic ideas is through music. Both diegetic versions of the “Imperial March” certainly fulfill the role of musical propaganda. The propagandistic qualities are evident in the use of music to hype up the Empire and Imperial military and conceal the atrocities both entities have committed. Russell’s version creates enthusiasm for the Empire during an Imperial holiday, while Powell’s entices people to join the Imperial military. A quotation that represents the prevailing attitudes of the early twentieth-century British Empire comes from organist Charles Albert Edwin Harriss, who described how he perceived British music’s role in Canada: “To make people—through the medium of music—play their part in the Empire is the propaganda which has engrossed public attention since away back in 1901” (quoted in Barker 2006, 172). This goal, a further aspect of imperialist propaganda, is present in both diegetic cues. In Rebels, one of the parade’s many goals is to excite people about working in the Imperial factory on Lothal, whereas the goal of Solo’s recruitment ad is to recruit people for the Imperial military and “play their part in the Empire.” Music is just one aspect of the Galactic Empire’s propaganda to achieve these goals.

The fact that the same source melody generates both diegetic cues suggests that the Galactic Empire’s use of music relates to another aspect of British imperialist music: music as a form of cultural imperialism17. The British Empire used cultural ideologies, including music, to build stronger ties between the indigenous populations and Britain and maintain control and influence over them. Consequently, the bands became “a musical weapon, and a thunderous proof of western military and religious superiority” (quoted in Herbert and Sarkissian 1997, 171). If the parade on Lothal is any indication, it would seem that the Galactic Empire also utilizes culture to control its citizens. The parade is primarily military in nature, but the inclusion of music played by a band native to the planet indicates that music has at least some role to play in the Empire’s overall scheme to have complete control of the galaxy. Although the band is, at least in Russell’s imagination, native to Lothal and not imported by the Empire, the fact that they play a version of the “Imperial March,” which is also used for the recruitment ad, indicates that the music played is likely part of a larger plan of cultural imperialism. The idea of a band made of the Indigenous populations of a colonized land is not foreign to the British Empire and possibly provides a reason for the use of the “Imperial March” in this scene: the British Empire would often have bands of indigenous people led by someone who studied in England, usually also native to England. Should the band on Lothal function the same way—with the musicians being native and the bandleader imported—the use of the theme makes much more sense (Herbert and Sarkissian 1997, 172 and Zealley and Hume 1926, 52). The parade exemplifies how the Empire used music as a weapon to influence every aspect of life on Lothal, from regulations on trade to importing Imperial music for the parade.

Beyond the connections between these two Empires, the musical relationship suggests something more profound—using the same musical style for the Rebels and the Empire suggests that the two groups are not as different as the Original Trilogy would have us believe. Previous examples of British-style music in Star Wars have always been associated with the Rebels, whether in the “Throne Room” cue or the Battle of Hoth sequence. The Powell cue, in particular, suggests that the politics of both groups are not as black and white as they might seem—in hearing the style accompanying the Galactic Empire, the hidden associations between that style and authoritarianism in this earlier cue come to the foreground. Indeed, Powell relies on precisely this unease to make his anti-British Empire joke work in the Solo cue. Although he does not discuss music specifically, Wetmore Jr. also notes this ambiguity: “The rebellion does not exist to achieve liberation for the oppressed indigenous peoples—it seeks to restore the previous privileged to power… The disenfranchised of the galaxy remain so, regardless of which group is in power. The Empire uses violence to suppress and the Republic simply ignores the margins” (Wetmore Jr. 2005, 38). The two diegetic versions of the “Imperial March,” in addition to acting as a sort of national anthem for the Empire, also highlight the grey areas between good and evil, between the Rebels and the Empire. The timing of these two versions, after Disney’s acquisition of Lucasfilm, is not surprising as Disney-era Star Wars has not shied away from this ambiguity, presenting characters on both sides that do not conform to the stereotypes of good and evil.

Conclusion: Long Live the Empire!

Williams’s “Imperial March” clearly did not have just one influence; it is a combination of many different musical styles that, when combined, produce a unique theme capable of expressing the villainy and threat of the Galactic Empire. Many of these proposed influences are Russian and German composers, with the exception of Holst’s The Planets and Elgar’s First Symphony. The two diegetic versions of the march, especially that of John Powell, bring both the British imperialist resonances of the original theme to the forefront and suggest connections between the Galactic and British Empires. More than solely foregrounding one of Williams’s many inspirations, the influence of British imperialist music provides further commentary on the Galactic Empire itself. Further, the influence of the British style on both Williams’s theme and subsequent versions of it puts into question the dichotomy between good and evil presented in the Original Trilogy, proposing that the Rebels and the Empire are more similar than the three original films portray. In addition to revealing how the British Empire influenced the Galactic Empire, this connection also provides commentary on the British Empire itself. Suggesting that the British Empire partially influenced the Galactic Empire allows the British Empire to be read through the lens of this connection, thus highlighting the more negative aspects of the British Empire.

Although the musical connections provide essential commentary on both Empires, the enduring popularity of the theme is most likely more related to the iconic villain it portrays than to these real-world comparisons. Even if the theme’s popularity is not a direct result of the real-world or musical resonances discussed in this article, each of Williams’s many references that inspired the theme comments on various aspects of the Galactic Empire. The Tchaikovsky theme is often—but not always—associated with the ballet’s villain, Rothbart, bringing evil sorcery, control, and manipulation to mind. Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet suggests a link to the Soviet Union and represents a fateful clash between two opposing forces. Shostakovich continues the Soviet Union connection while also invoking Shostakovich’s own commentary on—and turbulent relationship with—the Soviet government, lending the march a sardonic flavor. The Wagnerian influence reinforces the relationship between the Galactic Empire and Nazi Germany mediated by the Nazi’s use of Wagner’s music, but the chord progression itself has associations with evil sorcery. Holst brings in the connection to war and militarism, and the astrological origins of The Planets imply a sense of fate or destiny as well. Funeral marches continue the link to the military while also drawing on associations with death and processional music. The British connection, however, brings the processional music even more to the foreground and suggests ties to the military, the British Empire, imperialism in general, and the grey area between the Rebels and the Empire.

In drawing on such diverse references, Williams provides rich commentary on and significance of the “Imperial March” that goes beyond the images on screen, giving the theme a much deeper meaning. Like any composer, many of these influences are subtextual, primarily a result of Williams’s assimilation of these styles into his own musical vocabulary, but even if not conscious on the composer’s part, these references provide signification and resonances. Although the theme’s associations within the films are comparatively static, Williams delivers commentary on the nature of the Dark Side, the Empire, and Darth Vader by drawing on comparisons to real-world totalitarian regimes, imperialism, the nature of good versus evil, and the militaristic aspects of the Empire.