Thirty years after its premiere in 1993, Jurassic Park stands firmly in the canon of great blockbuster films. Steven Spielberg’s creature feature represents a true watershed in Hollywood’s visual vocabulary. In today’s CG-saturated Hollywood landscape, it is too easy to forget just how historic were the film’s advances in computer-generated imagery, and how aptly monumental the end of those advances—nothing short of the resurrection of a menagerie of long-extinct, never-before-seen colossi. Released six months before Schindler’s List, Jurassic Park contributed to something of an annus mirabilis for Spielberg, a year of unprecedented commercial and critical success after a handful of critical misfires in the previous years (Always in 1989, Hook in 1991). The movie’s cultural imprint today remains, deep and reverberant as the footfall of its most celebrated character, Tyrannosaurus Rex.

John Williams’s score, at the time his then thirteenth in collaboration with Spielberg, is no less well-regarded. While overshadowed in the year of its release by Schindler’s List (which understandably and deservedly garnered more sales, awards, and general critical goodwill), Jurassic Park’s music remains a fixed and beloved component of the broader “Jurassic imaginary” that persists to this day. If the existence of recent think-pieces in outlets like GQ, NPR, and—not to be underestimated as a source of deep musical discourse—YouTube are any indication, Williams’s colorful symphonic score retains a powerful fascination thirty years on.1

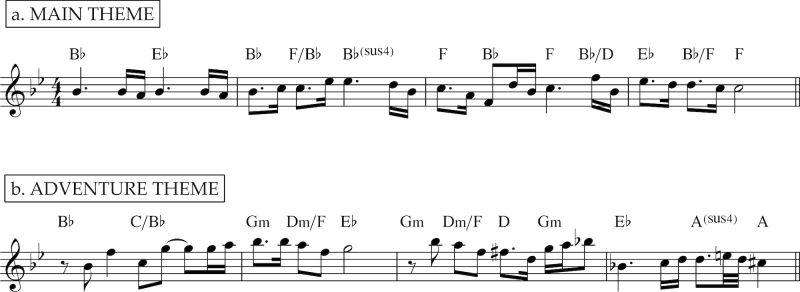

At the center of Jurassic Park’s musical reception history is its theme. Or, rather, its themes. What is frequently referred to as the “Theme to Jurassic Park” is in actuality a concert suite arranged by the composer in 1993 and subsequently published by Hal Leonard in the Williams Signature Edition series. This piece is effectively a musical diptych. The suite’s first half presents an extended version of the hymn-like Main Theme, drawn from the scene in which the protagonists first witness the Brachiosaurus early in the movie (“The Dinosaurs,” with the cue designation 3m2). Figure 1a shows the opening (mm. 8–11) of this melody, assuredly one of Williams’s most instantly recognizable.

Following the presentation of the Main Theme comes a modulatory transition (mm. 36–46 of the suite) based on a subsidiary, more lyrical idea heard in only one cue (14m2, “Leaving the Island”). From there, the suite launches into a rendition of the score’s brassy and harmonically wide-ranging Adventure Theme (Figure 1b), its fifty-odd measures imported with minimal alteration from the helicopter arrival sequence (2m3, “To the Island”).2 Filling in the edges of the arrangement (not shown) are a short preamble (mm. 1–7) centering on a four-note solo horn motto faintly connected to the score’s Carnivore Motif (much more on this later), and a brassy climax and codetta drawn from the “End Credits” plus the conclusion of “T-Rex to the Rescue” (14m1).

Figure 1

Jurassic Park, transcription of melodies featured in “Theme from Jurassic Park.”

a. Main Theme. Film (16:37), OST Track 4 (05:07),

b. Adventure Theme. Film (20:23), OST Track 4 (01:25).

Unlike most other post-Jaws soundtracks by Williams, from which he generally extracted multiple contrasting stand-alone arrangements, this “Theme from Jurassic Park” was the sole representative of the score prepared and conducted by the composer for concert use. Williams was also curiously hesitant to revisit much of the material from Jurassic Park in its 1997 sequel, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg). A remarkable score in its own right, albeit far less iconic, The Lost World is very much its own musical animal: it makes only sporadic citations of the Adventure Theme, hosts a single cue based on the Carnivore Motif, and treats the audience to a rather perfunctory replaying of the Main Theme at the movie’s conclusion.3 Indeed, it is this “Theme from Jurassic Park” that enjoyed a surprising resurgence in interest in 2015, during the build-up to Jurassic World (Colin Trevorrow, 2015), when it clawed its way back to the top ten—admittedly in the humble domain of streaming instrumental tracks on Spotify.4 Nevertheless, this upswing in popularity was an achievement noteworthy enough to garner several articles in various newspapers and trade magazines (Maloney 2015; Trust 2015). Even with an unsteady dissemination following the original film, the noble and nostalgic melodic pair of the Main and Adventure themes is undoubtedly what comes to mind for most who recall what Jurassic Park “sounded like.”

Musical canons are, of course, selective and reductive by their very nature. But few cases in the canon of film music—or film musicology—are so misleadingly selective or reductive as the case of Jurassic Park. The dominance of the score’s “Theme From” has led to a near-total neglect of the vast majority of the actual soundtrack, shockingly little of which is based on those two famous melodies. As a result, appreciation of Williams’s actual achievement has been barely recognized outside of a few small insider fan communities, and has been oddly neglected in the John Williams studies literature besides a single, highly perceptive analysis by Chloé Huvet (2014).5 Missing from the concert suite, rousing as it is, is any suggestion that the bulk of the Jurassic Park score is not so melodious. Indeed, the primary theme itself only occurs three times in the movie, albeit in admittedly famous scenes! Rather, the overall soundtrack is at turns atmospheric, horrific, and pulse-quickeningly exciting. This less melodious material is less accessible for concert or billboard purposes (and less iconic for nostalgia-generating ones), but altogether more illustrative of Williams’s technical mastery—in particular his unique alchemy of twentieth-century modernist ingredients and profoundly retrospective, romanticizing musical idioms.

Recent contributions to John Williams studies have helped direct analytical attention towards less strictly melodic matters.6 Nevertheless, there remains a strong emphasis in the study of this composer—and film music theory as a whole—on theme (or leitmotif) as a fixed object, as opposed to an active, evolutionary agent within the processes of dramatic underscore.7 This essay is offered as something of a corrective, if a provisional one: to better our understanding of the Jurassic Park score, and Williams’s art more generally, I will draw attention to precisely those corners of the soundtrack that are not defined by the aforementioned “big two” themes that have so dominated discourse and reception of this musical text.8

My central case study is a pair of cues, “A Tree for My Bed” and “Remembering Petticoat Lane.” The latter is a “one-cue wonder”: a discrete span of film music, which (on first glance at least) is athematic and without anticipation or corroboration elsewhere in the score. “Petticoat Lane” (10m1) is set apart from the rest of the Jurassic Park soundscape both in its eschewal of already-established leitmotifs and its dissimilarity in tone from either the majestic materials (over)represented in the suite, or the more typical suspense and action underscore that supports the bulk of the film.9 It comes paired with “A Tree for My Bed” (9m3), with which “Petticoat Lane” is almost contiguous. That cue does foreground a recurrent melody—the Main Theme—though in a way that reveals interesting new layers of meaning, rather than merely replicating the simplistic awe and splendor of its more famous guises. Together, these two cues form a larger sequence that might be called Jurassic Park’s celesta interlude, a musical refuge that foregrounds the instrument’s unique timbre and draws from its rich array of extramusical codes and emotional resonances.

Beyond its singularity within the melodic and timbral soundscape of Jurassic Park, the celesta interlude (01:21:43–01:28:29) is an attractive subject for music analysis for two reasons. First are the sequence’s complex and, for a blockbuster of this sort, subtle themes. I mean “theme” not in the musical sense, but rather as an interpretive issue or narrative concern. The interlude thematizes the interlinked affects of wonderment and nostalgia, elements at the very core of Williams’s and Spielberg’s aesthetic. In a less obvious but no less potent way, “Petticoat Lane” also thematizes issues of commerce, illusion, and even the ideology of entertainment itself.

The second commending feature is the fact that the celesta interlude comprises a span of quiet dialogue underscore. That such an oasis of calm music occurs within a soundtrack that is, for long stretches, written at an ear-shredding forte, is remarkable in itself. Focusing on this span of low-key music thus fills an additional lacuna in John Williams studies. When not focused on flashy recurring themes, analytical attention has naturally tended to fall on loud and foregrounded cues like action set-pieces or love scenes—music that, by the composer’s own admission, is often in something of a competitive relationship with other demands on the audience’s attentional bandwidth, especially sonic (think roars, screeches, stomps, and so on). This is at the expense of understanding the delicacy of Williams’s quieter moments, a topic made somewhat more difficult to broach from a scholarly perspective because the composer himself rarely speaks to his process with respect to non-thematic, self-effacing dialogic underscoring. Granted, Williams may be at his most memorable with big set-pieces and broad themes. But what makes him a master film composer is his sheer musical emotional intelligence, his intuition for when to pull back, when to insinuate, ruminate, to gently stir feelings or memories—all without drawing attention to the score as such—or, as the celesta interlude demonstrates, ever compromising technical rigor or musicality for which the composer is so admired within the industry.

Close inspection of “A Tree for My Bed” and “Petticoat Lane” will lead us down a number of interpretive avenues. After a quick summary of the sequence as a formal unit, we will consider the self-reflexive, even self-critical, quality of Hammond’s monologue and the peculiar subjectivity being represented through its accompanying music. This will lead to an examination of three style topics—the berceuse, the bagatelle, and the music box—that infuse both cues and provide stylistic continuity with other musical works both within and outside Williams’s oeuvre. The most music-analytically intensive portion of the article follows, re-associating the ostensibly standalone “Petticoat Lane” with the rest of the Jurassic Park score, through its embedding of the pervasive (and also seldom discussed) Carnivore Motif. While edifying as a purely formal exercise, insofar as it demonstrates the motivic economy and inventiveness in Williams’s underscore, the analysis is motivated by a more hermeneutic concern, one which strengthens and complicates the self-reflexive reading proffered at the beginning of the analysis. A somewhat more rhapsodic conclusion rounds off the essay, in which we consider the nature of musical codes and consider the responsibilities of analyzing the less-obviously thematic aspects of John Williams’s art.

Seeking sanctuary

Two-thirds of the way through the action-packed runtime of Jurassic Park, there is a seven-minute oasis of quiet, celesta-filled calm. Having barely survived the jaws of T-Rex, Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and the kids Timmy and Lex (Joseph Mazzello and Ariana Richards) retire to the jungle canopy to rest and recover. Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), fresh from her own close call with the surprisingly fleet-footed beast, heads to the park’s cafeteria to find John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), alone with his thoughts. These two paired scenes are where the movie catches its breath. The characters find, if briefly, sanctuary from the carnage surrounding them. This occurs in terms both spatial (in an unreachable treetop; in the proactive arms of an adult) and psychological (under a parental figure’s watchful eye; in gustatory pleasure; in the throes of nostalgia).

The first scene sees Grant, the erstwhile child-hater, assuming the role of surrogate father to the traumatized Lex and Tim. From their arboreal perch, Grant indulges in some sonic communing with the herbivorous—if still intimidating—sauropods dining in their midst. Once this serenade concludes, the “A Tree for My Bed” cue gently emerges. As the kids nestle into Grant’s embrace, he offers them both the individualized comfort they need: humoring Tim’s bad but tension-puncturing jokes, and promising to stay up all night to watch over Lex. Before drifting off, Lex asks Grant, “What will you and Ellie do now if you don’t have to dig up dinosaur bones anymore?” Grant answers, “I don’t know, I guess. Guess we’ll just have to evolve too.” The scene’s melancholic concluding shot is an obvious but elegant visualization of character growth: Grant tosses away the fossilized raptor claw he has held onto like a talisman. The claw, previously an emblem of his inflexibility and dedication to a now-obsolete profession (and, more symbolically, his lack of parental instincts) is now just deadweight. Grant has far more important things to care about.

“A Tree for My Bed” continues, bringing a shift of scene to the visitor center, with a slow and loving pan over Jurassic Park-branded toys and merchandise. One might think this would be an astonishingly self-undermining juxtaposition of genuine sentiment with almost sacralized treatment of commercial merchandise, were it not presented with such earnestness!10 As it happens, that very earnestness is discreetly challenged in the exchange to come. Sattler, spying Hammond alone, eating a cup of melting ice cream, offers him an update on Ian Malcolm’s (Jeff Goldblum) recovery. A short gulf of un-scored sound separates the end of “Tree for My Bed” and “Petticoat Lane.” The latter cue commences as soon as Hammond begins reminiscing on his early career, when he was a much more modest species of showman. As it forms the textual crux of the analysis in this chapter, the whole exchange is worth reproducing.

Dialogue Between Hammond and Sattler

Hammond: You know the first attraction I ever built when I came down south from Scotland? Was a Flea Circus, Petticoat Lane. Really quite wonderful. We had a wee trapeze, uh, a merry-go… carou… carousel. And a seesaw. They all moved—motorized, of course. But people would swear they could see the fleas. “Oh I see the fleas, mummy! Can’t you see the fleas?” Clown fleas, and high-wire fleas, and fleas on parade. [Pauses] But this place… I wanted to show them something that wasn’t an illusion. Something real. Something they could see and touch. An aim not devoid of merit.

Sattler: But you can’t think through this one, John, you have to feel it.

Hammond: [Chuckles]. You’re right, you’re absolutely right. Hiring Nedry was a mistake, that’s obvious. We’re over dependent on automation, I can see that now. Now the next time everything’s correctable.

Sattler: John…

Hammond: Creation is an act of sheer will. Next time it will be flawless.

Sattler: It’s still the flea circus. It’s all an illusion.

Hammond: When we have control…

Sattler: You never had control! That’s the illusion! I was overwhelmed by the power of this place. But I made a mistake too! I didn’t have enough respect for that power, and it’s out now. The only thing that matters now are the people we love. Alan, Lex, and Tim. John—And they’re out there where people are dying… [Pause to wipe tears.] So… [Reaches for ice cream]. It’s good…

Hammond: Spared no expense…

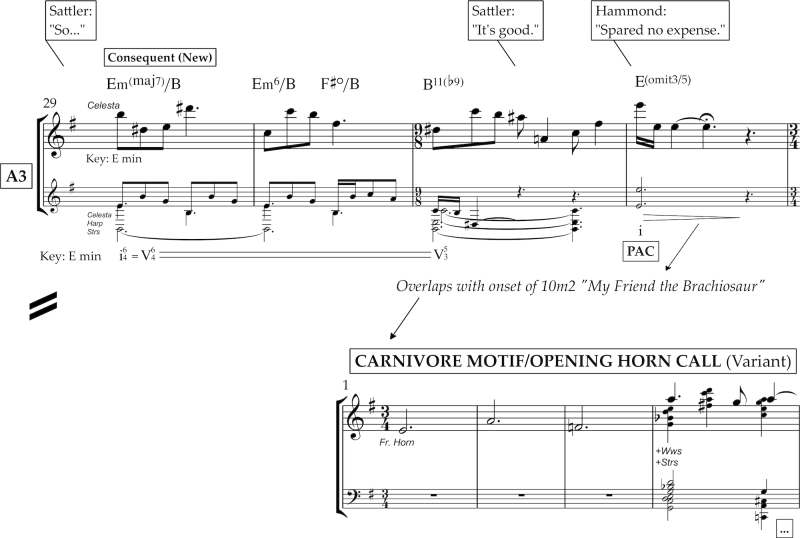

The celesta interlude concludes with a scene transition back to Grant’s treetop, now bathed in morning’s light. The end of Williams’s “Petticoat” overlaps with the onset of the next cue, “My Friend, the Brachiosaurus” (10m2). This piece begins with a solo French horn intoning a pacified variant of the Carnivore Motif before launching into more luscious, quasi-impressionistic music for an up-close encounter with one of the gigantic leaf-eaters.

Credit is due to Spielberg and his screenwriter David Koepp for this sequence. The two scenes conjoined by the celesta interlude make up one of the more thoughtful ruminations on the responsibilities of art and the power—and risks—of fantasy, among many in Spielberg’s filmography. Truthfully, the scene-pair is rather “on the nose,” in the sense that it renders explicit several themes that were previously only implied in the narrative: Grant’s discarded raptor claw as a symbol of his out-of-date and unsympathetic mindset, Hammond’s flea circus as a well-intentioned but equally-fake precursor to Jurassic Park, Sattler’s reproach of Hammond’s exploitative and inhumane reliance on technology. Sattler’s accusation concerning the illusory, hubristic nature of human control has to it the makings of a more drastic critique, even if her character does not go so far as to explicitly implicate the theme park industry, or, more broadly, the whole entertainment industry under late capitalism. Still, with those shots of plush dinosaur toys and expensive Jurassic Park-branded desserts fresh in the filmgoer’s mind, it is hard not to hear Sattler’s criticism as Spielberg and Koepp’s way of implicating not just Jurassic Park the park, but Jurassic Park the film.11

The celesta interlude is a musical character study, providing listeners a glimpse into Alan Grant’s subjectivity, then Hammond and Sattler’s in alternation. The empathic identification both cues elicit enables in turn a non-verbal point of access into the film’s conversation with itself. Williams’s music here reflects on the film overall, on its ethics, the illusory nature of spectacle, and the hollowness of the virtualized sublime. As argued by Constance Balides in her essay “Jurassic Post-Fordism,” the “Petticoat” scene permits Sattler an almost-radical social analysis because at the end, the character endorses a basically conservative “family values” kind of solution to the ills represented by the park. Sattler refrains from challenging the underlying wonderment-for-profit system. Balides notes that “Jurassic Park foregrounds the presence of its own products, and in this moment of commercial self-reflexivity, makes its own merchandising economics explicit” (2000, 150). She goes on:

Curiously, while Jurassic Park celebrates its commercial success, it also critiques the theme park mentality as well as the entrepreneurial culture underpinning neoconservative ethics… In Jurassic Park, the ethical problem of the commercialization of science in the park is resolved by the ethics of the new familialism. The film negotiates its critique of Hammond’s entrepreneurialism (“spared no expense”) and overweening techno-hubris (“next time it will be flawless”) by displacing ethics onto affect (“you can’t think your way through this one, John, you have to feel it”) and systemic critique onto personalist solutions (“the only thing that matters now are the people we love”)… (Balides 2000, 155–156)

Balides’s diagnosis, part of a larger analysis of film’s self-implicating political economy, is persuasive. And, with only minimal adjustment it may be applied to Williams’s score, as we shall see. There is an audacity to the sequence as a whole. Any tent-pole action film that takes a minutes-long break to pick apart its own ideological foundations—and unsubtly inculpate its filmmakers and audiences alike!—is worth admiring. Perhaps, the sequence’s ideology is strained, incoherent even, due to the film’s mixed-messaging. But, as Balides rightly contends, these ideological fissures make the sequence, and the film as a whole, far more engaging for the audience than a didactically clear warning about this late-capitalistic systemic ills could ever be.

Regardless of its aesthetic coherence or political efficacy, there is a clear ideological strain conveyed through imagery and dialogue in this scene: a tension between admiration for and suspicion towards the Jurassic Park project. The cues that constitute the celesta interlude also replicate this anxiety, and arguably with less hedging, more emotional directness and honesty, than the screenplay itself. “Petticoat Lane” especially seems to strip away a layer or two of the artifice and manufactured sentiment central to the Jurassic Park project, be that feeling uncomplicated awe (such as heard in the Adventure Theme) or fear (such as heard in any number of dissonant, frantic suspense cues). With these cues, by contrast, the filmgoer is offered a richly ambivalent, quiet nocturne in which Williams expresses a complex and ultimately irresolvable mix of regret, wonderment, and guilt.

While both cues are united by their celesta obbligato, an instrument whose associations we shall examine presently, it will serve first to inspect how the affective gestalt of the interlude is based on an important tonal contrast. “A Tree for My Bed” is completely diatonic: not a single pitch across its twenty-six measures belongs outside the governing D major scale. “Petticoat Lane” meanwhile is bristlingly chromatic, even though its primary theme is no less functional than its predecessor. (Its tortured middle section is a different matter, as we will see).

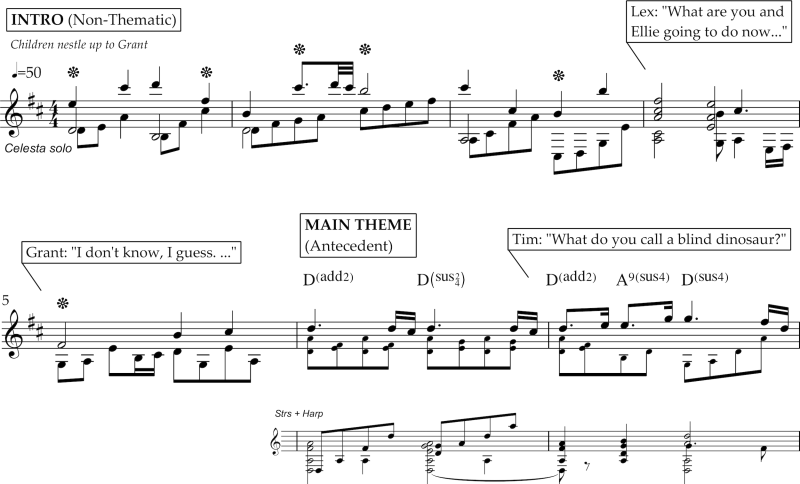

Figure 2 displays the first seven measures of “A Tree for My Bed.” The opening five bars consist of a celesta solo based on silky two-voice counterpoint. This sets the berceuse-like tone of the whole cue before it launches into the film’s Main Theme (only the first two bars of which are rendered).

Figure 2

Jurassic Park, “A Tree for My Bed,” transcription of first 7 measures.

Film (01:23:28), OST Track 10 (00:01).

Even its moments of dissonance—note the assorted added-note and suspended chords within the Main Theme—are diatonically referable. The celesta solo glances by non-consonant vertical intervals harmlessly, particularly in its opening sentence, whose various unprepared sevenths, ninths, and elevenths as often as not fall on strong beats. These glints of dissonance are indicated with asterisks in Figure 2. Without this bed of safe, entirely traditional harmony as an overture, the chromatic and restive “Remembering Petticoat Lane” would lose a great deal of its contrastive valence. “A Tree for My Bed,” in its guileless diatonicism, does not just serve the immediate needs of tucking Grant and the kids away in a cozy tonal bed; it provides an affective conduit into Hammond’s monologue, into his childlike mindset as the purveyor of (genuine) fakes and (mechanically reproducible) wonders.

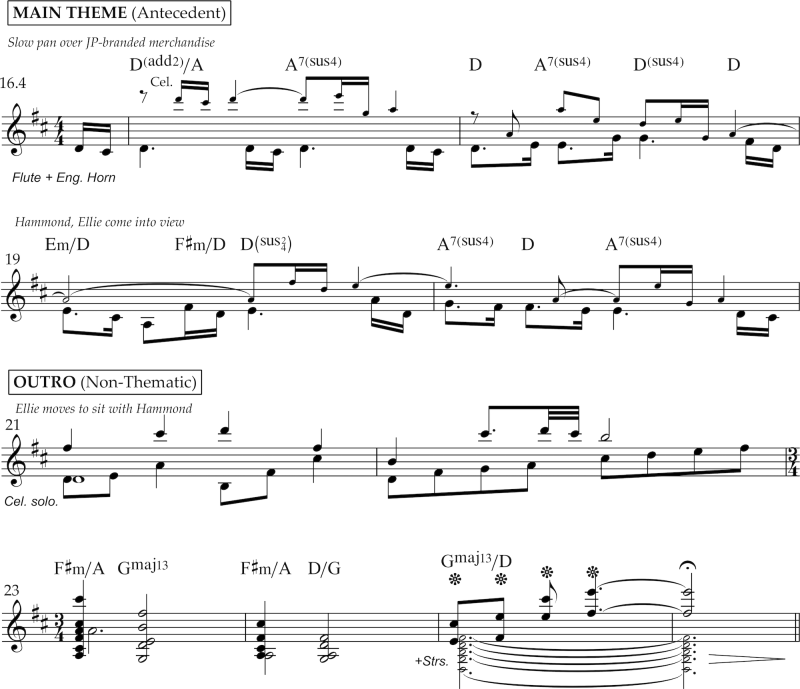

On a larger scale, “A Tree for My Bed” consists of two rotations through the Jurassic Park Main Theme, which correspond to a pair of slow-moving camera shots. The first rotation accompanies a crane shot moving slowly away from the children, safely nestled in the arms of their reluctant guardian. The second, rendered in full in Figure 3, follows the aforementioned loving pan over the lunch boxes, stuffed dinos, and other crass park merchandise. After securely cadencing in its twenty-first measure, the cue concludes with a recollection of the opening celesta solo. As Sattler joins Hammond at the café table, Williams allows the cue to trail off on a pair of widely-spaced dyads (E4+C♯5, F♯4+E5) that rise over a wistful diatonic cluster in the strings (an inverted G-major13 sonority)—a hint of tensions still unresolved, but nevertheless still radiating major-mode warmth.

Figure 3

Jurassic Park, “A Tree for My Bed,” transcription of final 10 measures.

Film (01:24:47), OST Track 10 (01:19).

As noted earlier, the Main Theme is surprisingly infrequent within the runtime of Jurassic Park, making its extended airing in “A Tree for My Bed” all the more salient. The other two iterations come at similarly powerful moments. The first, famously, is disclosed as Sattler, Grant, and Malcolm—here functioning as audience surrogates—behold for the first time the dinosaurs by the lake (19:50). In that context, the wellspring for the concert suite mentioned earlier, the melody is offered almost like cinematic sacrament: a sublime hymn, replete with literal “oohs” and “ahhs” from a wordless chorus.12 The variation offered in “Tree for My Bed,” by contrast, is domesticated into the least threatening, least sublime genre imaginable: a lullaby. The third iteration, which arrives at the very end of the film (01:58:06), blends timbral and affective elements of the first and second.13 In that guise, the Main Theme accompanies a visual echo of the tree-top scene, with Lex and Tim again safely sleeping on Grant’s shoulders as he and the rest of the survivors are elevated high above danger—now in a helicopter racing away from Isla Nublar. Beginning with a soft, solo piano rendition, the melody surges into a grand orchestral rendition that ushers in the movie’s credits. Here, at the end, Williams effectively synthesizes the domestic and epic aspects of the theme.14

The Bagatelle, the Berceuse, and the Music Box

Several veins of dark irony only lightly suggested in “A Tree for My Bed” are mined in the subsequent “Petticoat” exchange. Put reductively, Spielberg, Koepp, and Williams are baiting the audience. First, they lure and console the filmgoer with sweets: imagery of home and hearth, heartwarming dialogue, thematically familiar music. Then, with the viewer’s defenses lowered, the filmmakers can steer them into discomfort—a tense confrontation of characters, a scratching at the film’s ideological underpinnings, a haunted and at times keenly dissonant musical set-piece. It is in this respect that the guileless mood of “A Tree for My Bed” is strategic; a child’s nightmare hits harder if they were lovingly tucked into bed beforehand. On its own, Williams’s “Petticoat Lane” cue would be too much an outlier, detached from both the affective and thematic substance of the score as a whole. But with its beautiful, consoling predecessor introducing the musical terms (timbral, topical) and thematic stakes (affective, philosophical), the first half of the celesta interlude guides—or perhaps lulls—the filmgoer into Spielberg’s moment of self-reflexivity and incipient social criticism.

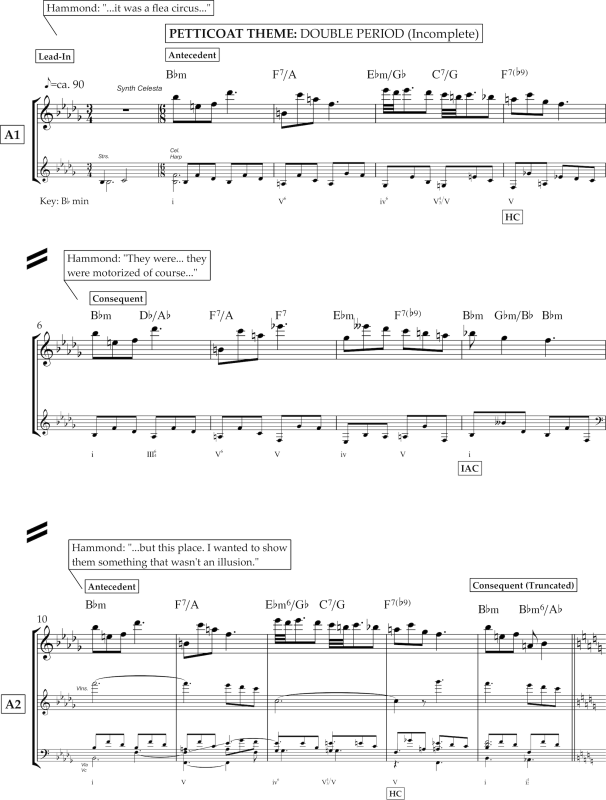

In fact, a comparable strategy of first lull, then challenge is enacted at the level of cue construction in “Petticoat Lane.” The piece is structured as a rounded binary form. Figures 4a through 4c depict the three portions of this cue, along with annotations to indicate where each line of Sattler and Hammond’s dialogue falls. The first paragraph (4a) presents a bittersweet but still reassuringly traditional and predictable celesta melody, the Petticoat Theme. It is followed by a much more discursive, often unnerving slice of musical prose (4b) wherein the celesta goes silent in favor of more plaintive sounds from solo winds and dark strings. The final four measures (4c) consist of a truncated recollection of the opening’s tune. More than serving as a mere symmetrical bookend to the cue, these bars restore—or, more forcefully, reassert—balanced, harmonically functional melody as the primary driver of, and emotional bedrock underneath, the Jurassic Park score. Those final measures also ease the entry into the next cue, “My Friend the Brachiosaur.” A variant of the film’s opening four-note horn motto (also shown in 4c) is another seeming throwaway detail that will turn out to be fairly significant in drawing the celesta interlude’s motivic threads taut.

The Petticoat Theme treads a thin wire between outward plainness and inward sophistication. It is a simple—but by no means a simplistic tune—more world-weary than ingenuous, particularly by the standards of the “naïve” compositional tropes identified by Jacob Friedman (2025) that Williams applies to comparable cues involving memories of youth. Nearly every measure features a surprising octave displacement, a plangent leap, a chromatic alteration, or all three. Figure 5 renders the theme in two ways. At the bottom of the diagram is a direct reproduction, with every melodic and harmonic interval indicated, and those that are dissonant (both in absolute and local, contextual terms) flagged with asterisks. The top of the diagram is a rhythmic reduction that displays the melody’s essential structure.

Several nice details emerge from this analysis. Note the infrequency with which vertical and horizontal dissonances coincide, despite the preponderance of unexpected pitches and odd contrapuntal configurations. Besides one convergence across the bar line of measures 1–2 (the horizontal d10 to d9, a vertical M2), Williams is studied in his avoidance of linear preparation/resolution of non-consonant sonorities. Note too the delicate mirroring of the theme’s concluding phrase, which pivots on a melodic inversion (mm. 2–3: F4 to E♭5 versus mm. 6–7: E♭5 to G♭4). Many other such details could be singled out: the composing out of a chromatic double neighbor figure, the convoluted counterpoint in measure 7, the whiff of the minor flat submediant in measure 9. Collectively, these touches lend the Petticoat Theme an uncanny air, a sense upon hearing that one is not sure exactly how such a musical object is able to operate as seemingly smoothly as it does.

Figure 4a

Jurassic Park, “Petticoat Lane,” transcription of mm. 1–14.

Film (01:25:57), OST Track 12 (00:01).

Figure 4b

Jurassic Park, “Petticoat Lane,” transcription of mm. 15–28.

Film (01:26:58), OST Track 12 (01:03).

Figure 4c

Jurassic Park, “Petticoat Lane” and “My Friend the Brachiosaurus,” transcription of mm. 29–32, 1–4.

Film (01:26:10), OST Track 12 (02:19) and Track 8 (02:29).

Figure 5

Jurassic Park, “Petticoat Lane,” underlying melodic and intervallic structure.

As noted, the “Petticoat” theme that appears in Figures 4a and 4c has little in the way of obvious linkage with the rest of the Jurassic Park score. It is, however, exceptionally dense when it comes to extratextual references and resonances. Foremost is a trio of closely related style topics, which shall be considered in turn: the bagatelle, the berceuse, and the music box. The bagatelle topic consists of an instrumental melody of a distinctively “old country” cast. Not quite a folk song but possessed of a certain vernacular accessibility, a bagatelle is very likely conceived for a pianist of modest ability. Although it has precedents in music of the early eighteenth century (Brown 2001), the genre is closely associated with Beethoven, who wrote several Bagatelle sets and singletons, the most famous of which is undoubtedly Für Elise. Bagatelles are light and sentimental in tone, often in the minor mode, and colored with a few poignant chromatic pitches, tangy dissonances, or expressive leaps. Their harmonies are functional but amenable to enrichment, and typically articulated through broken or arpeggiated chords (especially as triplets). While not contrapuntally inactive per se, linear interest is subordinated to a clear projection of a tune. More important than any one structural quality, however, is the topic’s essential affective remoteness: the bagatelle occupies a stylistic idiom that is both geographically foreign and somehow behind the times. It is affecting precisely because it is temporally and spatially displaced.

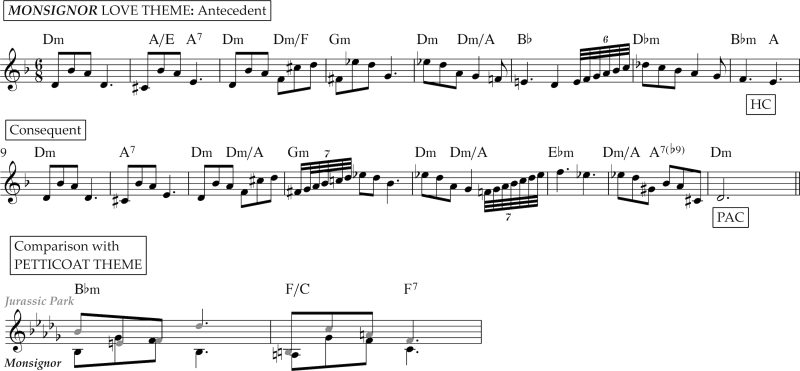

The bagatelle topic is seldom heard in Williams’s output, though there are some manifest precedents for “Petticoat Lane.” The clearest of these is the love theme for Monsignor (Frank Perry, 1982), a melancholic and vaguely Italianate piece, in its own context strongly identified with a solo trumpet. This theme is itself probably indebted to Nina Rota’s Godfather waltz (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972), perhaps cinema’s most iconic “old-country” style melody. Figure 6 displays the Monsignor tune in isolation, while a secondary staff juxtaposes it against “Petticoat”: note the degree to which the openings of these themes align, like neat little mirrors of each other.

Figure 6

Monsignor, transcription of the love theme and comparison with Jurassic Park’s Petticoat Theme.

More common in Williams’s output is the second major style topic active in the celesta interlude, the berceuse (alternatively lullaby, Wiegenlied). Defined by Kenneth Hamilton (2001) as “a gentle song intended for lulling young children to sleep,” trope-defining instances stem primarily from the nineteenth century, Chopin’s op. 57 Berceuse in D♭ being particularly important in codifying the genre’s expressive and formal expectations. Those expectations include: keyboard texture, compound time signature, tonic pedal point, and, as Hamilton observes, “a ‘rocking’ accompaniment oscillating between chords I and V.”

Williams-composed cues that invoke this consoling and soporific genre tend to overlap with the next style topic and its bell-like timbres, but a few of the most prominent instances make use of an instrument other than the celesta. Nodding to the Romantic-era’s instrument of choice for the berceuse, lullaby-like cues for piano may be found in the aforementioned finale from Jurassic Park, as well as Stepmom (Chris Columbus, 1998, “Always and Always”), The BFG (Steven Spielberg, 2016, “Finale”), The Fabelmans (Steven Spielberg, 2022, “Reverie”) and throughout A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001, “Reading Stories” and “The Reunion” especially). Two of Williams’s finest berceuses are played by the harp, an instrument otherwise rarely exposed in Hollywood scores in an extended or soloistic capacity. These showcases are the exquisite “Bed Time Stories” from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982), where the harp takes up the score’s Friendship Theme; and the pseudo-diegetic “Fluffy’s Harp Lullaby” from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (“Sorcerer’s Stone” in the United States, Chris Columbus, 2001), in which the instrument converses freely with an incongruous contrabassoon. Explicitly texted lullabies are uncommon, though several pieces from Home Alone (Chris Colubus, 1990) and Hook (Steven Spielberg, 1991) qualify, most plainly the leitmotif (and eventually diegetic song) “When You’re Alone” from the latter. As sung by the child Maggie (Amber Scott), this simple and sentimental tune proves capable of bringing a tear to the eye of even the most grizzled of pirates.15

The third style topic that animates the celesta interlude is the music box. Invoked implicitly in “A Tree for My Bed” but explicitly in “Petticoat Lane,” it is a musical symbol with vivid connotations and an extremely strong historical association with that specific, tinkling instrument.16 The music box-as-topic is more than just a vessel for the celesta timbre, however.17 The topos bears a particular textural character as well: a high tessitura and limited range; a simple but steady and non-rubato stream of note durations, especially through an Alberti-bass-style accompaniment. Similarly decoupled from the celesta timbre-as-such are matters of harmony (a simple progression, emphasizing tonic and dominant oscillations), and rhythm and meter (a preference for simple triple or compound duple meters, an elevated degree of figurational repetition).

With those structural markers in place, the music box topos conjures a host of expressive qualities, most notably childhood, domesticity, and intimacy. Additional connotations of wintertime, Christmas, magic, flight, dance, and play also attend the music-box topos in certain situations. The music box can also represent metonymically the idea of the “toy,” or more specifically, a mechanical plaything, a man-made object capable of automated but unnatural or artificial human action—perhaps a simple act of sound and musical production, perhaps something more.

Examples of music box topos, both literal and abstracted abound in Williams’s oeuvre.18 Table 1 offers a (non-exhaustive) gallery of uses and their subject matter. Starting in the late 1980s, most performances of celesta-based cues were rendered not on an actual celesta but a custom-designed synth sound created and played by keyboardist Randy Kerber (Caschetto 2022), thus effecting yet another remove from the “real” thing. Not surprisingly, the dramatic content of the scenes bearing these solos consistently revolves around those connotations mentioned before, with childhood in particular being virtually obligatory. While beyond the scope of this essay, a close study of these examples would reveal many subtle gradations of feeling and technique, and even an assortment of sub-topoi (especially in the Potter franchise). This kind of diversity within one topical umbrella is to be expected from a composer with such a longstanding affinity for, and opportunity to experiment with, the celesta timbre.19

Of course, the music-box topos is not unique to Williams’s output; it is both well-established and, in recent years, well-theorized in film music in general.20 Allison Wente observes that the timbre and texture of a music box are loaded with associations, not just with childhood and nostalgia, but a strange sort of inhumanity. These associations can be conjured in passages that explicitly utilize a celesta timbre or one of its cognates (glockenspiel, toy piano, etc.), but also in passages that employ those textural features to suggest or “sublimate” a music-box topic without the actual bell-like timbre. She observes that “mechanical instruments function more as toys than as instruments; they serve as markers of the past rather than placeholders for an absent performer… [The music box] creates a specific kind of musical work, the kind that requires no performer, no performance, and has no fallibility. It is perfect music—music without any sort of humanity. The music box is a spectacle of mechanical innovation.” (Wente 2013)

Table 1

|

Film |

Cue(s) |

Subjects |

| Heidi | “The Sleeping Child” | children, domesticity, nostalgia, lullaby |

| Jaws | “Father and Son” | children, domesticity |

| The Witches of Eastwick | “The Children’s Carousel” | children, magic |

| Empire of the Sun | “Toy Planes, Home, and Hearth” | children, domesticity, lullaby |

| Hook | “The Arrival of Tink” | children, lullaby, magic, night, winter |

| Home Alone 1, 2 | “Main Title” | children, Christmas, lullaby, night, winter |

| Home Alone 2 | “Turtle Doves” | children, Christmas, winter |

| JFK | “Garrison Family Theme” | children, domesticity |

| Jurassic Park 2 | “The Island’s Voice” | children |

| The Patriot | “Saying Goodbye” | children, domesticity |

| Harry Potter 1 | “Hedwig’s Theme” | children, lullaby, magic, night, winter |

| Harry Potter 1 | “Cast A Christmas Spell” | children, Christmas, magic, winter |

| Minority Report | “Last Scene With Crow” | children, nostalgia |

| Catch Me If You Can | “Empty” | domesticity |

| Harry Potter 2 | “Harry and Dumbledore” | children, magic |

| Harry Potter 3 | “Secrets of the Castle” | children, lullaby, magic, night, winter |

| Harry Potter 3 | “Honeydukes” | children, Christmas, magic, winter |

| Revenge of the Sith | “Finale” | children, domesticity |

| The Force Awakens | “End Credits” (Ending) | nostalgia |

| The BFG | “Dream Country” | children, lullaby, magic, night |

| The Last Jedi | “Finale” | children, lullaby, nostalgia |

| The Fabelmans | “Reflections” | domesticity, nostalgia |

| The Dial of Destiny | “To Morocco” | children, night, nostalgia |

Additional examples of music box topoi in Williams’s filmography.

The defining feature of the music box is thus the disconnect between its comforting, humane purpose and the robotic and error-prone mechanization of its output. “But if the music box breaks down,” a skeptic in the mold of Ian Malcolm might say, “the ballerinas don’t eat the tourists.” True, though in many cases music-box topics are recruited to produce just exactly this kind of threat. Stan Link (2010) argues that it is the total anempathy (in Michel Chion’s sense) of the instrument that renders it so apt for scenes of horror, especially those in movies involving children. There are indeed instances of such perverse music boxes in Williams’s filmography—Empire of the Sun (Steven Spielberg, 1987), The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987), and A.I. host distortions of the topic, while certain celesta passages in Star Wars: Episodes V – The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) and Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983) associated with the Emperor channel some of the spookier pages of Bartók. A most instructive instance is in “The Island’s Voice” from The Lost World, where a soon-to-be attacked young girl gambols on a beach to abstracted music box figures, floating high above a queasily dissonant orchestral bed. However, in the original Jurassic Park, the music-box topic is a near-complete counterexample to Link’s grotesquely uninterruptible music boxes. This is the opposite of anempathy—it is music that is pro-empathetic, even ultra-empathetic with respect to the words spoken and feelings expressed by the onscreen characters.

As the dialogue annotations in Figures 2 and 4a–c illustrate, the celesta part in both “Tree for My Bed” and “Petticoat Lane” closely follows the emotional beats of the screenplay. The affective congruency of score, dialogue, and image is borne out as much in moments of absence of this music box topic as its presence. Note, for instance, how the celesta drops out from “Petticoat Lane’s” timbral palette precisely when Hammond’s wistful reverie is dragged into the present by Sattler. Or how, at the end of the same cue, the celesta-defined Petticoat Theme does not complete itself perfectly. What sort of music box is this, we might ask, which does not continue mindlessly once spun up, but whose sonic cessation is in split-second accordance with the emotional affect of its surroundings?

Naturally, the film itself offers a neat “pro-empathetic” explanation for the sonic comings and goings of the music box. In the first case, the transition into the B section, the celesta disappears just as Hammond states “we’re overdependent on automation, I can see that now.” The timbre is thus rather elegantly mapped onto the scene’s subtext: a wind-up mechanism (music box, mechanized flea circus) must necessarily stop at some time, so it might as well be when the illusion of a working project it accompanies itself breaks down.

A less literal but equally emotionally sensitive justification can be offered for the truncated A section with which the cue concludes. The theme has been subtly transformed, cast in a new light. Sattler and Hammond are in a different psychic place than at the beginning of this interlude, and so too is the audience. It is thus appropriate that Williams’s theme should be presented thus: fragmented, tonally displaced, faintly chromaticized, a sad recollection. Doubly sad, in fact, as the closing musical sentence feels like a necessary but external imposition of closure, when the viewer and characters alike know well that the wounds opened and examined during the previous 28 measures are not yet—and may never be—sealed.

Hidden Carnivores

Having detailed various topical facets of the celesta interlude, it is worth returning to the issue of thematic versus athematic underscoring. As shown, “Petticoat Lane” operates outside the referential network defined by the two memorable ideas developed in the “Theme from Jurassic Park.” However, to say the cue is completely divorced from the motivic substance of the score as a whole is too hasty. A different, more subtle type of thematic relationship hides within the cue, only peeking out briefly, but to considerable dramatic effect.

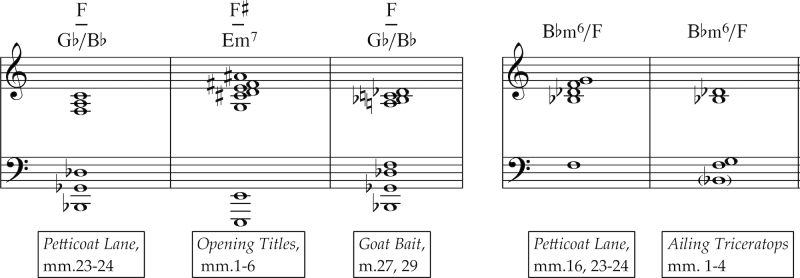

Jurassic Park is a score thick with strange and gnarly chords, from its first polychordal measure to its final, haunted cluster sonority.21 Quite a few of these pitch simultaneities have, if not full-blown leit-harmonic status, then hints of recurrence and development over the score’s runtime. And more than a few such chordal recollections occur in “Petticoat Lane.” Figure 7 displays two such echoes. The F-major over G♭/B♭ polychord that pulses uncomfortably in measures 23–24 finds a direct precedent in the F-major(♭6) over G♭/B♭ sonority from “Goat Bait”—a chord that leaves the listener in suspense as to whether T-Rex will appear to eat its restrained living meal. Both “Petticoat” and “Goat” chords in turn are indirect relatives of the opening title’s wash of F♯|Em7. A second harmonic interrelationship is less harshly dissonant: the recurring B♭m6/F chord in “Petticoat” is essentially just a lightly-enriched minor tonic chord, and has a clear, indeed at-pitch precedent in the opening sonority for “Ailing Triceratops.” There, the chord serves a similar tonal and affective function, initially heard as B♭m tonic, then, retroactively, a minor subdominant of F major.

Figure 7

Chords in “Petticoat Lane” heard elsewhere in Jurassic Park.

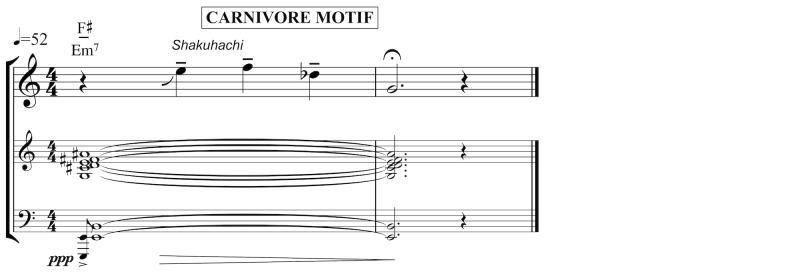

In their inconspicuous way, these and other recurrent verticalities help interrelate many of Jurassic Park’s non-thematic cues. Their function is arguably more to provide an element of harmonic consistency across the score than to produce any strong dramatic or affective meaning. This is not the case, however, for the one patently horizontal motif that thus far has not featured in our discussion, and which proves decisive in “Petticoat Lane”: the Carnivore Motif. Also referred to as the “Danger” or “Raptor” motif, this four-note motto stalks throughout the Jurassic Park score, appearing far more often than either of the two “Main” themes and furnishing material for some of its scariest moments and biggest climaxes. Figure 8 depicts its inaugural appearance, played with a marked degree “Otherness” by a shakuhachi, right after the aforementioned “Main Title” polychord.

Figure 8

Jurassic Park, Carnivore Motif in “Main Title” (mm. 5–6).

Film (00:39), OST Track 1 (00:18).

For the most part, the Carnivore Motif’s presence in “Petticoat Lane” is obscured. But during one moment, it does make a more overt appearance. Measures 15–18, described back in Figure 4b as a bridge into the more agitated B section, hold the key. As this seemingly nondescript music plays, Hammond finds himself reacting to Sattler’s urge that he cannot “think” his way through his dilemma, only “feel it.” We then see a stark change in his demeanor; no longer wistful or grandfatherly, he launches into a heated diatribe about control and creation. It is now clear: Hammond’s hubris is inextricable from his childish view of the world, a reckless lack of maturity or self-insight being the ultimate force that endangered his guests. Against this realization, a quiet, elongated variant of that Carnivore Motif is heard, materializing from the remnants of the preempted Petticoat bagatelle. Williams thereby draws through music a connection between Hammond’s recklessness and the carnage currently happening in the park.

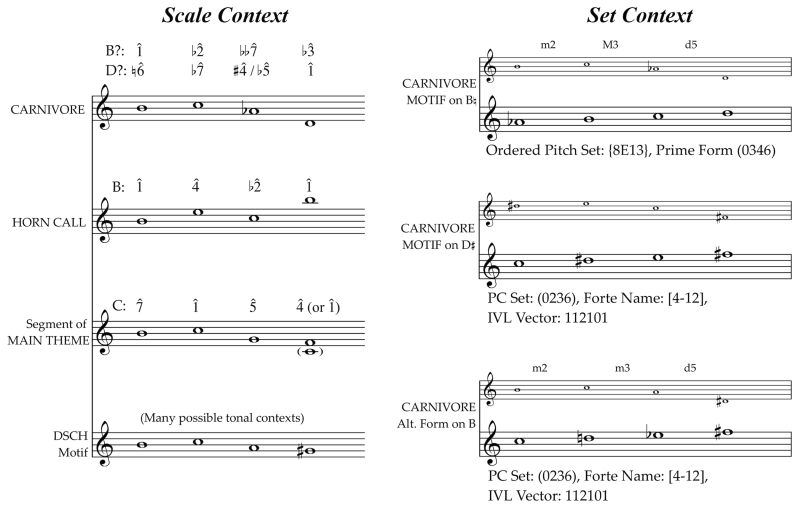

Most iterations of the Carnivore Motif elsewhere in the Jurassic Park score are more assertive in their orchestration, more insistent in their articulation, often directly hailing the presence of a meat-eating dinosaur. In all cases, the motif has a cruelly curved contour, not so unlike a musical raptor claw. Figure 9 offers a variety of analytical angles on this motif. Note that, in its standard form (here rendered as B-C-A♭-D), the motif is diatonically inadmissible. Those four pitches fit into no natural major or minor scale, and assimilate into a stable tonal setting only by the brute force of repetition or sustained pedal pitches. (In principle, the motif could emerge from the C harmonic minor scale, though no actual uses in Jurassic Park suggest such a context.) The motto is similarly difficult to squeeze into a commonly encountered chord, though Bdim7(♭9) and D7(♭5) can, with some finesse, host its pitch constituents.

Figure 9

Jurassic Park, analytical angles on the Carnivore Motif.

Given its incompatibility within common scalar or functional routines, it is more appropriate to treat the Carnivore Motif as a pitch-class set—that is, a constellation of intervals subject to the kinds of manipulations one expects from free atonal music. Specifically, the pattern is a (0236) tetrachord, or Forte set [4-12]. Among the striking traits of this set is the fact that, within its tight bounds, it can project every interval class save the paradigmatically consonant perfect fourth/fifth. On occasion, Williams offers a slight variant, also described in Figure 9, that proceeds down by minor rather than major third between its second and third pitches. When stated with its canonical contour (i.e. B-C-A-E♭), the result is a shrunken but strictly pitch-class-equivalent (0236) sonority.

Further contributing to the evocativeness of the Carnivore Motif are its various intra- and intertextual kin. These relatives are also depicted in Figure 9, along with their respective tonal implications. First is the horn call which opens the “Theme from Jurassic Park”—and, as we have seen, transitions from “Petticoat” into “My Friend, the Brachiosaur.” This tetrachord bears a passing—albeit diatonic—resemblance to the more chromatic Carnivore Motif. The same is true for the interior of the Main Theme itself. Admittedly, this B-C-G-F cell has a wildly different functional and phrase-formal setting, but at the same time an even more precisely matching up-down-down contour. And, outside of the realm of Jurassic Park, listeners familiar with the music of Shostakovich will hear an echo of that composer’s oft-recruited, comparably elastic musical signature (“DSCH”: D-E♭-C-B).22

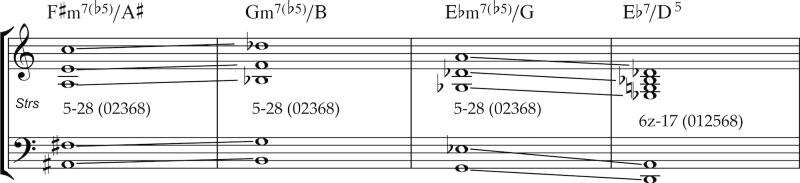

Despite its brevity (and a certain lack of singability), the Carnivore Motif is varied and developed thoroughly, insinuating itself into the score’s fabric to an extent extraordinary in John Williams’s output. A full accounting of the many guises of this particle is well beyond the scope of this essay, though a small gallery of instances will suffice to convey the ways in which this motivic talon sinks into the flesh of the score. Figures 10a and 10b display the idea in two guises from the film’s climax. The first is an intensely dissonant five-voice “harmonization” of the motif. While the four chords that support this variant can be considered tertian in origin, they may also be accounted for on a more neutral intervallic basis, as two stacked minor sixths (e.g. A♯2+F♯3 and E4+C5) with an additional major seventh (A3) in the middle, creating a 5-28 set. Figure 10b stems from the final action cue “T-Rex Rescue,” during which T-Rex-machina appears out of nowhere to do battle with two raptors. At this moment, the Carnivore Motif achieves an apotheosis of sorts, appearing in triple counterpoint with itself, most prominently in the trumpets and at various levels of pitch identity and rhythmic displacement or distension in the horns and trombones.23 Incredibly, this bravura passage was replaced in the final cut of the film with a clumsily tracked iteration of the Adventure Theme, totally destroying the telic satisfaction coming from seeing the Carnivore Motif in its full actualized state.

Figure 10a

Jurassic Park, Carnivore Motif in “March Past the Kitchen Utensils.”

Film (01:52:04), OST Track 15 (01:33).

Figure 10b

Jurassic Park, Carnivore Motif in triple canon in “T-Rex Attack.”

OST Track 15 (06:42).

Compared to the rip-roaring iterations that populate the above-cited action cues, the version of the Carnivore Motif that appears halfway through “Petticoat Lane” (mm. 15–18) is harmless and peaceable. At first it seems to bear just three distinct pitches of the motif’s four, its diminished fourth and fifths (an expected D♭4-A3 and A3-E♭3) softened into diatonic thirds and fifths (an actual D♭4-B♭3 and B♭3-E♭3). The result is a diatonic (0235) subset instead of the chromatic (0236) one. Nevertheless, the referent is undeniable once one is attuned to it, and the missing component is supplied in short order. Attending to the destination of the string line reveals the Carnivore Motif in its entirety. The pattern-completing pitch, E♮4, arrives in measure 20, where it assumes the role of anchor for the rest of the phrase, acting as the most registrally and melodically prominent component of the new A(♭6)/C♯ sonority. Set-class 4-12 is thus achieved precisely, pitch-ordering and contour alike. With the listener distracted by a change of orchestral texture, the clever motif was hiding in plain earshot.

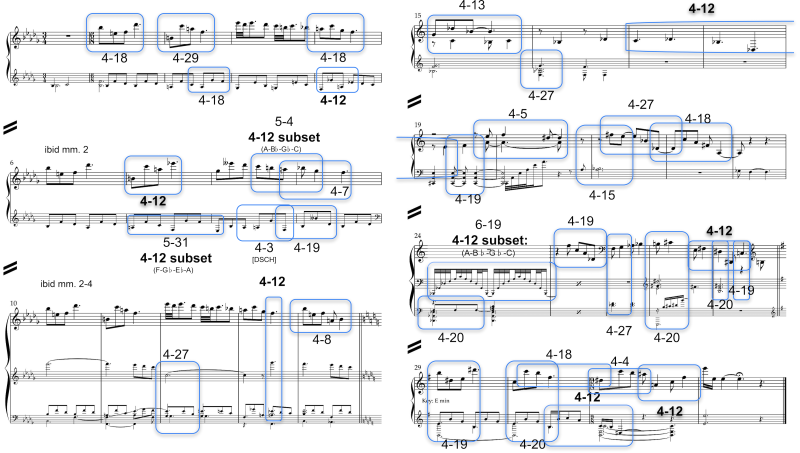

This concealed statement is not alone: the whole of “Petticoat Lane” is populated with carnivores. Indeed, what makes the cue such a remarkable example of Williams’s motivic ingenuity is the diversity of ways in which that four-note cell ramifies across its full duration. Figure 11 reveals an entire menagerie of harmonic references under the cue’s surface. At the risk of overcrowding, the annotated score focuses on sets of cardinality four (with just a few, highly salient supersets)—and of those tetrachords only those that are reasonably audible, involving no set-theoretically promiscuous segmentations or contortions.

Both the tonally secure A1-A3 sections and harmonically floating B1-B2 sections of the cue abound in prominent melodic tetrachords. In the former, those four-note sets are integrated into a functional context, first B♭ minor, then E minor. In the latter, they are allowed to agitate or even erase the feeling of a stable tonal center. Popping out of Figure 11’s analysis are several sonorities Williams is quite partial to. Note, for instance, the hexatonic 4-19 (0148) and 4-20 (0158) and octatonic 4-18’s (0147) interspersed through the cue.24 Many amount to dissonantly perturbed consonant triads in one configuration or another. The set of prime relevance, however, is undoubtedly 4-12—the “genetic code” for the Carnivore Motif.

There are seven instances of 4-12, all eminently hearable as such, none requiring segmentational contrivance. A further three sets of larger cardinality (5-31, 5-4, and 6-19) are also of significance in the cue, inside which sits a 4-12 subset, again perfectly audible. Nowhere is the Carnivore Motif ever rendered exactly in both pitch content and contour, but there are certainly some near-clones of the theme. Several spots are worth isolating:

- Measure 7: The melodic line here is a slight variant of the idea from measure 3. It hosts the Carnivore Motif in its proper pitch order (B-C-A-E♭), but hides the accustomed melodic shape behind a pair of octave displacements. The first pitch, B4, is an octave lower than the norm, and the second, E♭6, an octave too high.

- Measures 31–32: A similar play of registration as that in measure 7, plus an element of internal repetition, conceals an otherwise exact iteration of the motif, now in the accompaniment (B-C-A-[B-C]-D♯). Moments later, the melodic line, in its final gesture, plots the Carnivore Motif’s pitches transposed to A perfectly, and in the right registral stratum, but now out of order (A♯-A-C-F♯).

- Measures 27–28: The cello figure that bridges these two measures (E-F♯-D♯-C) is also outside 4-12’s accustomed pitch order, but its contour and rhythm marks it as clearly derived from the Carnivore Motif. Furthermore, the manner in which this cello line is set apart, recitative-like, relative to the rest of the texture, makes it almost more a vocal utterance than a musical one. The camera lingers on Hammond’s chastened face. Rendered speechless by Sattler’s reproach, the cellos here now are his voice, his interiority. These formal and audiovisual factors collectively render this moment perhaps the most intentional, explicit, and poignant iteration of the Carnivore Motif in the cue.

Varied, transformed, and concealed, the Carnivore Motifs skulks secretively through “Petticoat Lane” like an unseen threat. The cue’s dominant affect of nostalgic pathos is thereby inflected with something darker, more bloodthirsty. Sattler is right that Hammond never had control; musically speaking, the monsters are now running the show.

Figure 11

Jurassic Park, noteworthy four-note sets in “Petticoat Lane.”

Cracking Jurassic Park’s musical genetic code?

The scenes that make up Jurassic Park’s celesta interlude are, for a massive blockbuster, surprisingly complex and reflexive. Williams’s music, brimming with topics and echoing with motivic relations, supports the film’s self-critical stance while contributing ambivalences all its own. At the risk of a certain undermining of its premises, this article will conclude with a self-reflexive turn of its own. We began with a call to reduce our analytical fixation on themes and instead attend more to non-thematic underscore. And we ended up seeing that a span of ostensibly non-thematic underscore is in actuality suffused with thematic work, albeit of a concealed and definitely not hummable nature. In the foregoing interpretation of “Petticoat Lane,” one might be forgiven for thinking that music analysis has almost become an act of code-breaking. Especially to readers unacquainted with set theory, Figure 11 may appear like a conspiracy board. Such a bemused reaction is understandable, even if the findings of that diagram were offered with a genuine belief that they are meaningful, audible, and, if not provably intentional, then certainly the product of a rigorous and consistent compositional style. It is nevertheless worth pausing on the notion of the encoded, both within Jurassic Park and in film music analysis more generally. To do so in the context of this study is not a hermeneutic non sequitur: the film strongly thematizes the idea of coding and decoding, with references throughout to codes, mutations, recombinations, gap-filling, and sequencing. These notions all have suggestive correlates in film music analysis.

Screen musicologists familiar with Claudia Gorbman’s discipline-defining text, Unheard Melodies, may recall her discussion of “cinematic musical codes” (1987, 2–3, 12–13, passim). In essence, these are conventions that merge musical structures with culturally shared meanings. Regardless of the term (other authors call them tropes, topoi, musemes, clichés, or schemata), Gorbmanian codes enable diverse audiences to parse the informational density of the average film cue. However, after several decades of semiotically informed research in film musicology, there is now little mystery or intrigue behind how such cinematic musical codes work, at least not on a high level. What is of infinitely more interest is that musical material which does not clearly “encode” meaning, or which does so in a manner non-generalizable from listener to listener.

In the analysis offered of “Petticoat Lane,” I made a case for the subtle, maybe even covert presence of the Carnivore Motif, operating at the edges of audibility but contributing still to the ambivalent and self-critical content of the scene. To this end, set-analytical tools came in handy. With non-thematic underscore as an encrypted text and Carnivore Motif as its cipher, my analysis proffered a means of uncovering a sort of motivic coherence of the cue, one with interpretive significance and maybe more than a small suggestion of John Williams’s impressive craftsmanship.

Analysis, especially when backed with high-powered analytical machinery and motivated by a vigorous hermeneutic stance, is a creative act. It is also an assertion of control—control over a complex, multivalent, overflowing text. But, to channel Ellie Sattler, “you never had control! That’s the illusion!” Music analysis, when left to its own devices, tends to revert to an exuberant, sometimes heedless penchant for pattern hunting. But film music is not a code to be broken, and not every element needs to be “thematic” in order for it to be effective.

There is a term in the biological sciences that entered the mainstream in the 1990s: junk DNA. Although the term has since receded in usage as our understanding of the genome has increased massively (Wells 2011), the basic concept is still largely understood and accepted. It refers to the vast swathes of an organism’s genome that are not in charge of coding proteins, whose function is regulatory, auxiliary, or perhaps non-existent given our current scientific knowledge base (Carey 2015). The most surprising result of our ever-growing understanding of genetic code is that so much of it does not seem to directly “code” anything at all.

Film theory has its own version of this term: Kristin Thompson’s (1986) notion of cinematic excess. Like the “junk” in “junk DNA,” “excess” comes with unfortunate negative connotations that have dimmed enthusiasm for its application in recent years, but its basic meaning is not a value-laden one. Cinematic excess simply encompasses all the countless elements of a filmic text that do not contribute to the construction or delivery of its unifying narrative; it is the stuff that, while present, is not strictly necessary for telling a movie’s story.

Music analysis tends to be totalizing. One expects that the composer meant everything, that each note serves a vital purpose, all is unified. Such is the basic ethos of organicist analysis of all stripes, whether the organic elements are keys, cadences, sets, or motifs, to say nothing of all manner of multimedia relationships. Film music theorists, perhaps overcompensating for the old but tenacious anxiety that screen scores may be naught but musical wallpaper—a sonic gap-filler—are especially prone to this reflexive attitude.

No one who takes film music as an art form seriously would call anything composed by John Williams “junk.” And, even denatured of its negative connotations, Thompsonian “excess” still seems too categorical to capture how semiotically dense even throwaway passages tend to be within Williams’s brand of intense and self-foregrounding musical storytelling. And yet, even the most apophenic listeners must admit that it cannot all be code, that his music must include sequences that serve a less vivid topical or thematic function than others. Sometimes, a B-C-A♭-E♭-type tetrachord is indeed a masterfully camouflaged Carnivore Motif, skulking in the bush. Sometimes, it is just another four-note pitch succession. There are, after all, ultimately only 28 distinctive tetrachordal species: with a score as packed with notes as the typical Williams soundtrack, certain configurations are bound to appear by accident. Moments of motivic “convergent evolution” may occur alongside instances of genuinely directed thematic manipulation and mutation.

There is assuredly plenty of non-coding musical material in “Petticoat Lane,” if the code in question is the Carnivore Motif. As for the noted prevalence of 4-12 tetrachords, or any other unifying thematic detail, some analytical humility is warranted. Just because some concatenation of notes can be isolated from the texture and ascribed motivic salience in a written analysis does not mean it will—or even can—be heard in such a way. To paraphrase Dr. Malcolm, “we film music analysts were so preoccupied with whether or not we could [draw thematic connections] that we didn’t stop to think if we should!”

Luckily, it is entirely possible to pursue a rigorous and profound sort of film-music analysis, one that respects the too often-discounted realm of non-thematic underscore, while doing so in a way that does not purport to turn every last microsecond on the soundtrack into some musical gene or another. One need only follow a few simple analytical dictums.

- Seek musical corroboration. If a detail of musical design seems significant, look to other passages and other cues; finding it there will vastly support hearing said detail as significant, as something other than a happenstantial coincidence.

- Seek audiovisual corroboration. Meaning in film emerges from the conjunction, correspondence, and sometimes contest of different constructive parameters. The most incredible of musical connections means little if no other filmic parameter—dialogue, sound, editing, cinematography—marks it for the filmgoer’s attention somehow. This is not to say those parameters must signpost the presence or reinforce the meaning of that musical connection; film musicologists know well that sometimes non-alignment is as semiotically productive as simple congruency.

- Understand a film composer’s idiolect, as it is established over numerous scenes and scores. Take special heed of scores generically or chronologically close by. Sometimes a striking component of one soundtrack will turn out to be an idiolectical schema or mannerism that is consistently, perhaps unconsciously applied, across many. Never discount the pressure placed on the composer to emulate the film’s temporary (temp) track, even for the most accomplished figures like Williams.25 (For what it is worth, self-repetition or temp-track-itis is not the case with the Carnivore Motif, which does appear largely sui generis in Williams’s output, though only a thorough knowledge of his oeuvre allows the making of such a claim.)

Note that none of these principles are about establishing or disproving author intentionality. Filmic meaning—which includes the existence and significance of thematic connections— is ultimately produced by the listener/viewer, not the creator. To that end, a fourth dictum for responsible analysis is called for: resist the cryptanalytic stance for its own sake. Analysts of music for mainstream films ought to avoid the impulse to detect and reveal a “secret” embedded in their text.26 In general, Hollywood scores do not operate on a logic of obscurity or connoisseur-aimed intricacy; their codes, in Gorbman’s sense, need to be well-established and immediately legible. Which is not to say enormously intricate and subtle compositional processes might not be at play; indeed, we expect them from a composer like Williams, while also granting that even he is capable of writing on autopilot from time to time. And if it should happen that the analyst detects the inklings of some ingenious cipher hiding under the musical surface, they ought to proceed in a cautiously self-critical fashion, as hopefully has been modeled here.

Ultimately, the best course of action for film music analysts may be to emulate a modern geneticist. Spend time looking to the less obviously meaningful material. Examine it with the same seriousness and sustained attention—but also skepticism—with which one would approach the big famous tunes. Dismiss non-thematic underscore as a film’s “junk” DNA at one’s peril. On closer inspection, it may not be so non-thematic after all. But even if neat motivic interrelations do not emerge from careful study, that excessive music will almost certainly play host to a variety of style topics and expressive genres, from which a satisfyingly rich interpretive tapestry may be spun. This balanced, interpretive approach—neither hyper-focusing on melodic themes, nor obsessively hunting for invisible connections—is how, in the words of John Hammond, we provide the audience of film music scholars and appreciators “something that wasn’t an illusion. Something real.” A music-analytical aim not devoid of merit.