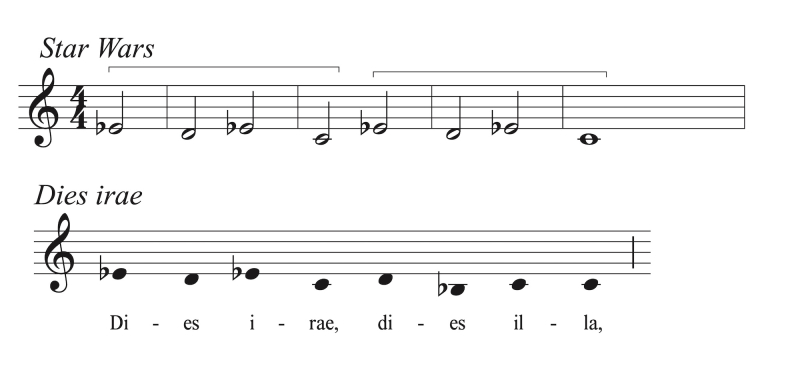

It’s become one of the most iconic moments in Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977). Luke Skywalker returns to his farm on Tatooine to discover that imperial stormtroopers have burned down his home and killed his aunt and uncle. This calamity propels the film into its second act and marks the beginning of Luke’s initiation into the ways of the Force. The music that accompanies this pivotal juncture climaxes with an ominous repeated four-note motif in the horns that captures the depth of Luke’s anger and despair (Figure 1; Clip 1).

Figure 1

Star Wars: A New Hope, Dies irae in “Return to the Homestead,” personal transcription.

Clip 1

Star Wars: A New Hope, Dies irae in “Return to the Homestead.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / 20th Century Fox / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357565

As several commentators have noted, John Williams alludes here to the first four notes of the most famous musical symbol of doom and perdition in the western musical tradition: the Gregorian chant Dies irae, or “Day of Wrath” (Lerner 2004, 104; Golding 2019, 126; Trocmé-Latter 2022, 42). Since its inclusion in the Requiem mass during the late Middle Ages, this apocalyptic hymn has been associated with death and the Last Judgment. As one of only four Gregorian sequences to survive the liturgical purges of the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century, its connection with mortality and the apocalypse was ingrained in the consciousness of European Catholics for many generations. In the early nineteenth century, Berlioz parodied the Dies irae in the last movement of the Symphonie fantastique (1830) to evoke a grotesque burial during a demonic orgy. Since then, the Dies irae has enjoyed a vigorous afterlife as a musical symbol of the macabre, morbid, and diabolical in works of Liszt, Rachmaninov, Mahler, Shostakovich, Crumb, and many others—including Williams’s composition teacher Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, who used the Dies irae in his 24 Caprichos de Goya for Guitar, Op. 195 (1961; Clip 2), a set of programmatic miniatures inspired by the etchings of Francisco Goya.1

In film music, the Dies irae has likewise had a long tradition as a musical symbol of perdition—as documented by musicologist Alex Ludwig, who maintains an ever-expanding inventory of Dies irae quotes in films from the silent period to the present (Ludwig n.d.; see also Schubert 1998, 207–229 and Trocmé-Latter 2022, 41–44). With fourteen scores, John Williams occupies a prominent place on Ludwig’s list.2 The pervasive use of the Dies irae as a melodic gesture in the music of Williams has become a matter of common knowledge in the film music community,3 and has spawned multiple online discussions and YouTube videos. The principal focus of scholarly attention has been on his use of the Dies irae in the Star Wars series and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977) (Ludwig 2025, 212–220; Lehman 2023, 28; Golding 2019, 126–128; Schneller 2014, 104–108; Lerner 2004, 104; Larson 1985, 298). What has been largely absent in the commentary so far is a systematic account of how Williams adapts the Dies irae as a melodic structure across a number of films, and why—beyond its generic association with death—it might be deployed in a variety of dramatic contexts.

In many films, the Dies irae represents a “foreign body” within the score—a self-conscious quotation that points outside the diegesis to previous films, operas, concert works, and liturgical music in which it has appeared as a harbinger of doom. Consider, for example, Hugo Friedhofer’s “Desperate Journey” from Between Heaven and Hell (Richard Fleischer, 1956) or the main titles from Jerry Goldsmith’s Mephisto Waltz (Paul Wendkos, 1971) and Wendy Carlos’ The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). A potential problem with quotation is that it draws attention to itself as a preexisting musical object and thus risks distracting spectators from full immersion in the world of the film by reminding them of other films or pieces of music in which it has appeared. “A quotation is an intrusion,” as Raymond Monelle puts it (2006, 166). Perhaps for this reason, Williams generally eschews literal quotation of the Dies irae in favor of alluding to it subliminally through fragmentation, paraphrase, or reconfiguration of its melodic structure. The first four to six notes of the theme provide raw material from which he crafts new melodic units that can function as autonomous leitmotivs while still preserving a recognizable connection to the original point of reference—a procedure that allows him to seamlessly integrate the Dies irae into the fabric of his own music without sacrificing its culturally pre-encoded semantic charge. By remaining just below the threshold of outright quotation, he can activate the cluster of ominous associations connected to the Dies irae in the spectator, even if the source of these associations does not rise to the level of conscious recognition.

The Dies irae in the music of Williams is thus best interpreted as a topical referent rather than a quote, and in that sense it functions like other musical topics in his music that have been the subject of recent scholarly attention (e.g., marches, fugues, and action scherzi).4 Instead of being literally copied, the semantic payload of particular historical models is invoked through skillful allusion to their essential features. Film music has always relied on topics: conventional, semantically charged musical signs that can efficiently convey a wide spectrum of affective and conceptual information (e.g., the “femme fatale” topic with silky strings and sultry saxophone).5 In theory, this reliance on prior knowledge of culturally encoded meanings extrinsic to the filmic narrative differentiates topics from leitmotifs, which relate intrinsically to the narrative.6 But this distinction is blurred in practice, since most leitmotifs in film music are infused with topical significance. As Matthew Bribitzer-Stull emphasizes, “themes are mutable musical individuals that may embrace generalized topical stereotypes. Associative themes are at their most powerful when they invoke topical resonance […] to cement a piece-specific meaning” (Bribitzer-Stull 2015, 115). By the same token, the Williams Dies irae retains its status as an indexical topic that subliminally “points to other repertory as a symbol of death and destruction in [the] western musical canon” (Everett 2009, 53) while simultaneously functioning as a distinctive leitmotif that relates in specific ways to the diegesis of the films in which it appears.

In this article, I will argue that the “topical resonance” of the Dies irae in the music of John Williams is anchored primarily in the text of the original Gregorian hymn rather than its macabre reincarnations in Romantic music. As a musical symbol associated with the concepts of guilt and punishment as well as death, the Williams Dies irae throws into relief not merely the morbid but, more importantly, the moral dimensions of the filmic narrative—an approach typical of the composer’s encyclopedic knowledge of, and sensitivity to, the deeper semantic implications of particular musical gestures. In the case of the Dies irae, this process involves a set of transformations of the source melody that appear repeatedly in his body of work, as I will illustrate by examining ten scores across a variety of genres including legal thrillers, science fiction, and war films.

The Williams Dies irae: structure

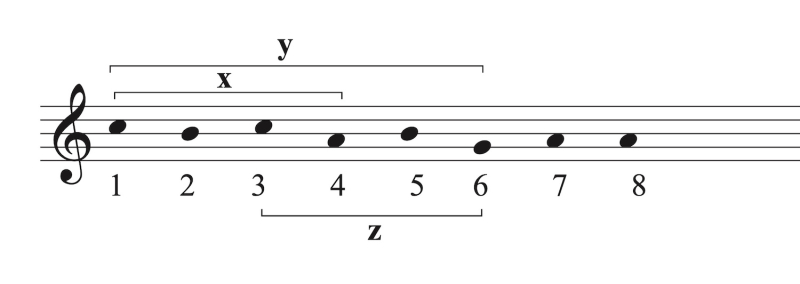

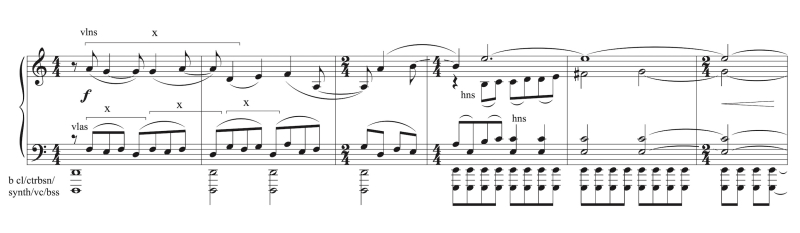

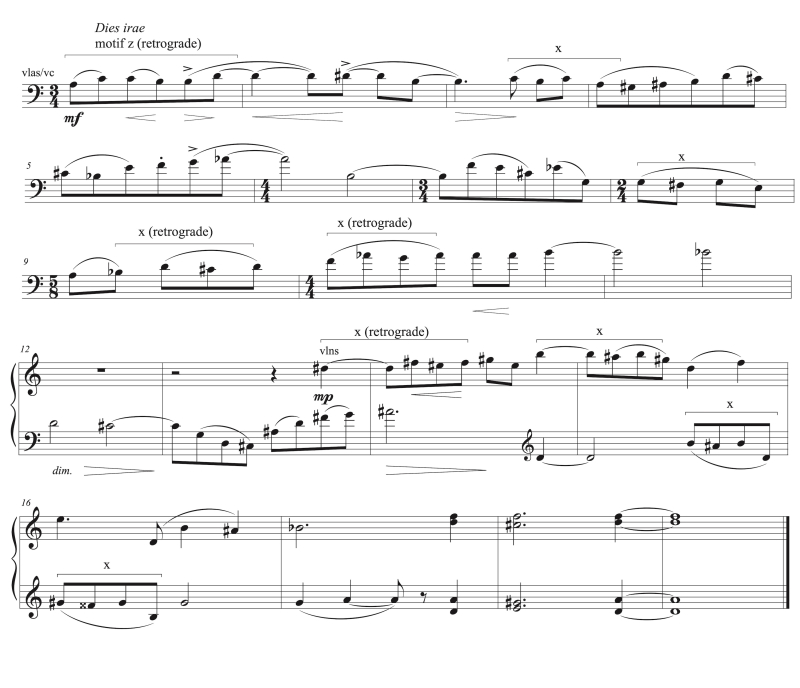

Before delving into a semantic analysis of the Williams Dies irae, let us consider its syntactic aspects. Like most composers who allude to the Dies irae, Williams restricts himself to the first phrase of the original chant. Within that phrase, he draws on three particular motivic segments that I have labelled x, y, and z (Figure 2; Clip 3). Motif x consists of the first four notes of the Dies irae; motif y utilizes the first six notes; and motif z consists of a pair of descending thirds derived from notes 3 to 6 of the Dies irae.

Figure 2

Motifs derived from first phrase of Dies irae.

Clip 3

Motifs derived from first phrase of Dies irae.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357516

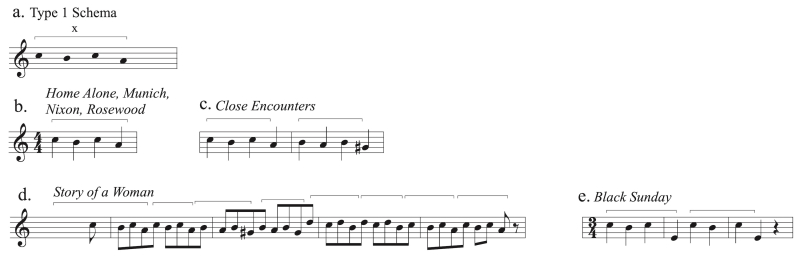

Williams uses these three motivic derivatives separately or in combination to create at least seven distinct variants or “types” of the chant melody.7 Type 1 consists of motif x—that is, the first four notes of the Dies irae. This is by far the most commonly used manifestation of the chant in Williams’s work (Figure 3b; Clip 4). Type 1 can be extended through sequential transposition, as in Close Encounters, or through repetition and transposition, as in Story of a Woman (Leonardo Bercovici, 1970) (Figures 3c and d). Note that it is common for Williams to substitute a lower pitch for the last note of the pattern, as in Black Sunday (John Frankenheimer, 1977, Figure 3e).

Figure 3

Dies irae Type 1 (4-note schema consisting of motif x).

To facilitate comparison, all themes in figures 3–9 have been transposed to A Minor.

Clip 4

Dies irae Type 1 (4-note schema consisting of motif x).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357539

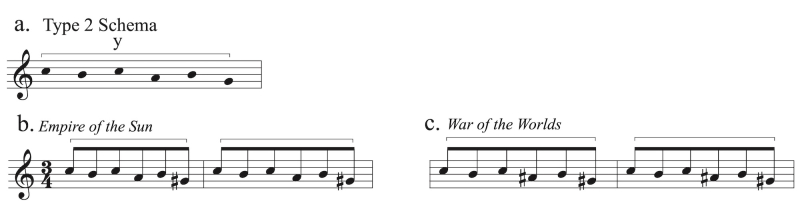

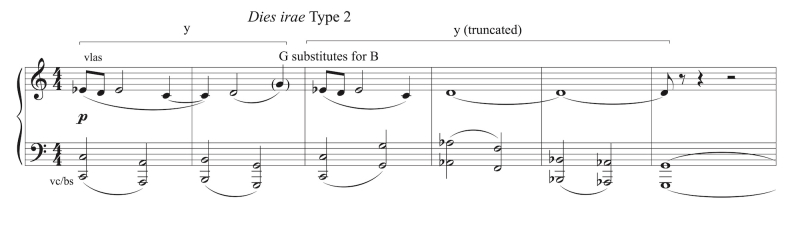

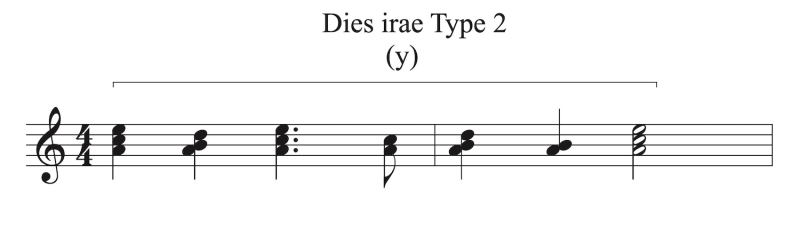

Type 2 consists of the first six notes of the Dies irae. Instead of the modal subtonic of the original, Williams typically raises the seventh scale degree, as in Empire of the Sun (1987)—a harmonic inflection that allows the motif to be smoothly integrated into octatonic or harmonic minor pitch fields (Figure 4b; Clip 5). Other pitches can also be inflected chromatically, as in War of the Worlds (2005), in which the outline of the Dies irae, in accommodation to the predominantly atonal harmonic idiom of the score, is compressed into the intervallic space of a chromatic cluster (Figure 4c).

Figure 4

Dies irae Type 2 (6-note schema consisting of motif y).

Clip 5

Dies irae Type 2 (6-note schema consisting of motif y).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357589

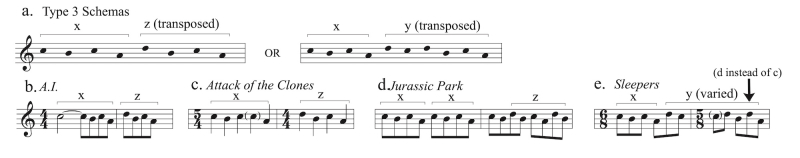

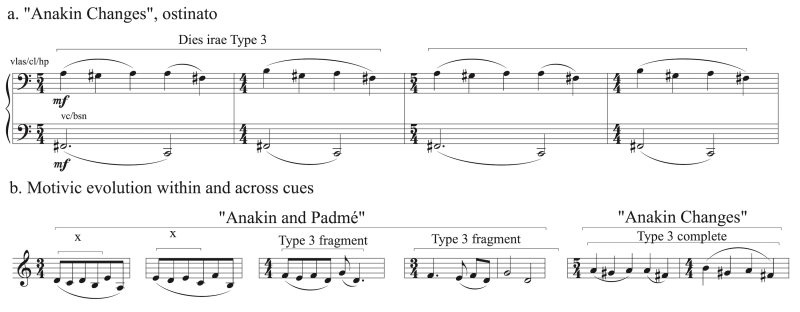

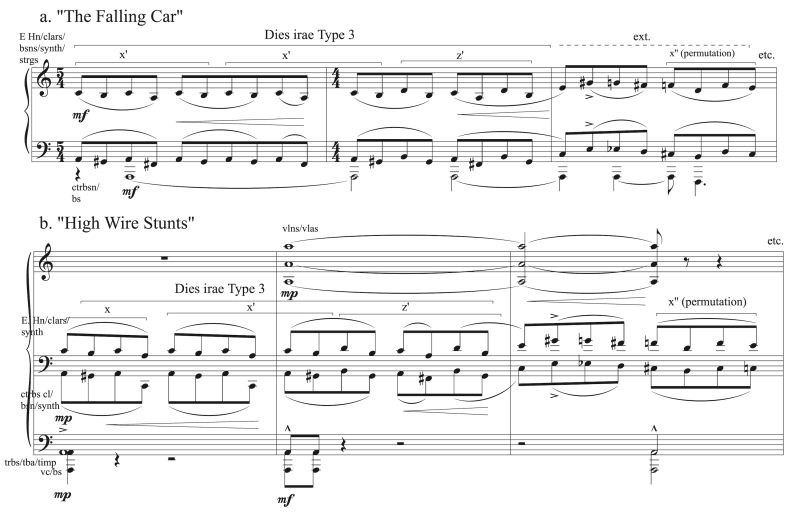

Type 3 combines motif x and the descending thirds of motif z, transposed up a step to start on scale degree 4 instead of 3. This variant appears, for example, in “The Journey Through the Ice” from A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001, Figure 5b; Clip 6). Type 3 can be varied through interpolation of repeated notes, as in Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002, Figure 5c) or extended through repetition of segment x, as in Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993, Figure 5d). A more complex variant of Type 3 appears in Sleepers (Barry Levinson, 1996, Figure 5e).

Figure 5

Dies irae Type 3 (motif x + motif z or y of Dies irae transposed to start on scale degree 4).

Clip 6

Dies irae Type 3 (motif x + motif z or y of Dies irae transposed to start on scale degree 4).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357606

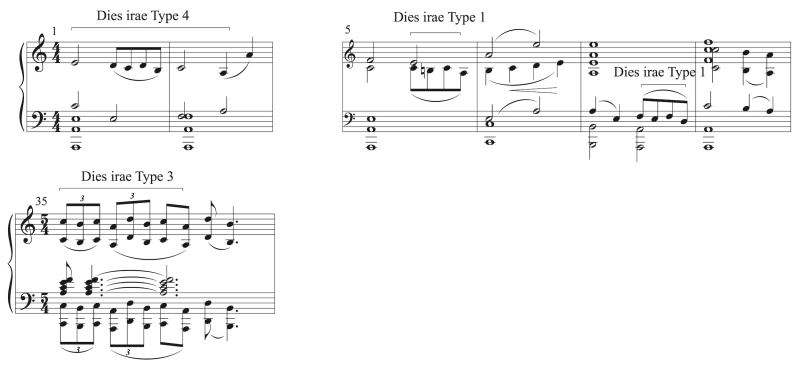

Type 4 starts on scale degree 5 and descends to the tonic by way of one or two statements of either x or y. This variant appears in War of the Worlds and Munich; here, both segments of the phrase present motif x, starting on scale degree 5, then transposed down a third. In the second segment, the schema is embellished through the repetition and interpolation of single pitches (Figures 6b and c; Clip 7). A variant of the schema can be observed in “Anakin’s Betrayal” from Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith (George Lucas, 2005), which makes its way down to the tonic by way of motif y (Figure 6d).

Figure 6

Dies irae Type 4 (starts on scale degree 5, descends to tonic by way of x or y).

Clip 7

Dies irae Type 4 (starts on scale degree 5, descends to tonic by way of x or y).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357643

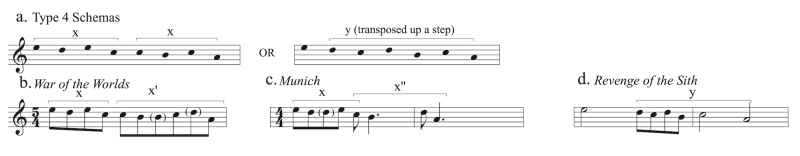

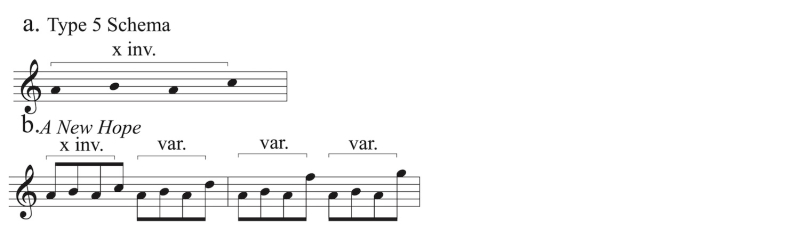

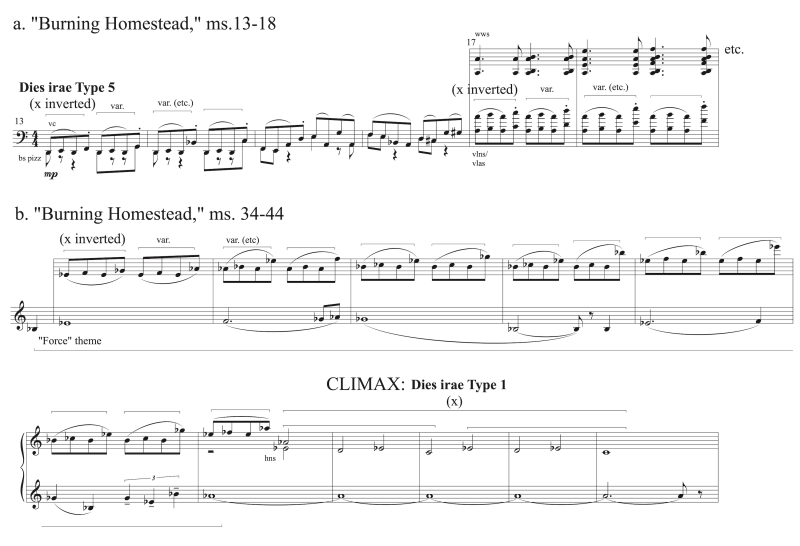

Types 5 through 7 can be heard as distant, but nonetheless audible, derivatives of the Dies irae (provided, of course, that the musical and dramatic context justifies such a reading). Type 5 consists of the inversion of the four-note head motif x (Figure 7a; Clip 8). This can be extended and varied through repetition of the first three pitches and ascending stepwise transposition of the last pitch, as is the case in the “Burning Homestead” cue from Star Wars: A New Hope (Figure 7b), in which the inversion of motif x serves as a build-up to a climax based on its original form (see Figures 1 and 18).

Figure 7

Dies irae Type 5 (inversion of motif x).

Clip 8

Dies irae Type 5 (inversion of motif x).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357622

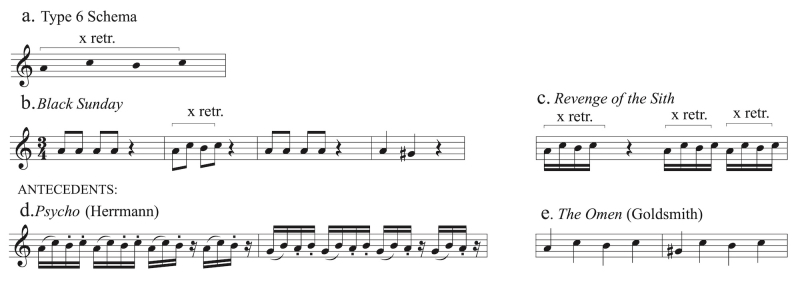

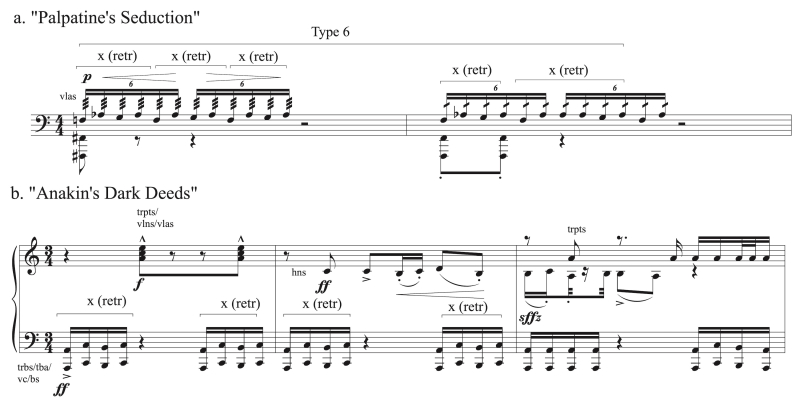

Type 6 consists of the retrograde of motif x. This particular pattern has important antecedents in horror scores such as Herrmann’s Psycho (1960, Figure 8d; Clip 9) or the “Ave Satani” from Jerry Goldsmith’s The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976), in which the backward Dies irae serves as a musical analogue of the upside-down cross of a Black Mass (Figure 8e). In Williams’s score for Black Sunday, which was released the year after Goldsmith’s Omen score won the Oscar and is clearly influenced by Goldsmith, the retrograde of the Dies irae is incorporated into the motif for another diabolical figure—the terrorist Dahlia (Figure 8b). Williams made particularly effective use of the Dies irae retrograde in what Frank Lehman has dubbed the “Sith Seduction” motif from Revenge of the Sith (Figure 8c, Lehman 2023).

Figure 8

Dies irae Type 6 (retrograde of motif x).

Clip 9

Dies irae Type 6 (retrograde of motif x).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357657

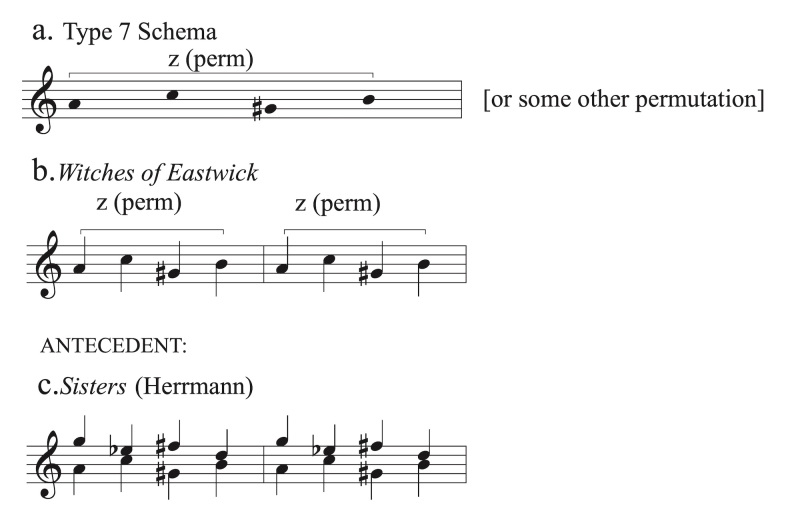

Finally, Type 7 presents a reordering of the adjacent thirds of motif z so they form ascending rather than descending thirds.8 This variant of the Dies irae is employed in The Witches of Eastwick (1987), where it is associated with the devil (Figure 9b; Clip 10). Like Type 6, Type 7 has antecedents in horror film scoring, particularly in Bernard Herrmann’s music for Sisters (1972, Figure 9c), which combines motif z in the top line with Type 7 in the counterpoint.

Figure 9

Dies irae Type 7 (permutation of motif z).

Clip 10

Dies irae Type 7 (permutation of motif z).

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357677

Williams deploys these variants of the Dies irae’s opening phrase in two principal ways: as a self-contained unit which can either stand separately as an independent motif or be deployed as accompanimental figuration to a principal theme; or as a semantically marked segment embedded within a continuous stream of otherwise non-motivic eighth notes.

Semantic aspects of the Williams Dies irae

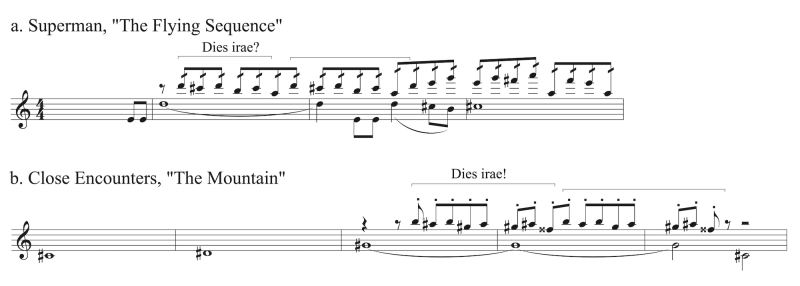

The determination of whether a melodic line resembling the first phrase of the Dies irae should be regarded as a meaningful allusion is dependent on whether or not such a reading can be justified by the dramatic context. It is not convincing to automatically label every occurrence of the patterns in Figure 2 as an instance of the Dies irae, since the phrase and its derivatives constitute attractive melodic shapes that need not function symbolically. In the “Flying Sequence” from Superman, for instance, Williams uses a Dies irae-like melodic gesture as a mellifluous counterpoint to the B section of the sweeping love theme (Figure 10a; Clip 11). Only through an act of analytic contortionism could one interpret this accompanimental figure, which occurs in an exuberantly romantic scene, as a reference to the Dies irae (might the counterpoint subtly foreshadow Lois Lane’s subsequent temporary demise in the aftershock of the earthquake caused by the atomic missile detonated by Lex Luthor in an attempt to unleash nuclear Armageddon? Probably not).

Now consider “The Mountain” from Close Encounters (Figure 10b), which uses a very similar melodic gesture, again as a counterpoint to a principal theme. In this case, hearing the counterpoint as an allusion to the Dies irae makes perfect sense, considering that it is based on a motif foregrounded throughout the score as the musical signifier of a potential impending apocalypse (for a detailed analysis of the semantic implications of the Dies irae in Close Encounters, see Schneller 2014).

Figure 10

Comparison of Dies irae-like melodic patterns in Superman and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Clip 11

Comparison of Dies irae-like melodic patterns in Superman and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357744

To plausibly interpret a Dies irae-like motif as an allusion we would generally expect it to occur within a context congruent with the various symbolic meanings accrued by the Dies irae over centuries of use in liturgical, concert, stage, and film music.9 These meanings change depending on whether we consider the original plainchant or the plethora of nineteenth and twentieth century works in which it is quoted. As Daniel Trocmé-Latter notes, in instrumental works of the Romantic era the “hortatory elements of the ‘Dies irae’ text are almost entirely lost, replaced instead by a ghoulish or terrifying prospect of a secularized imagining of what awaits us after death” (2019, 40). In the same vein, most film composers resort to the Dies irae simply as a convenient musical shorthand for “death in a simplistic—sometimes abstract—and usually secular sense” (Trocmé-Latter 2019, 41). Williams, by contrast, seems to consistently associate the Dies irae not just with death but also with guilt and punishment—concepts that evoke the fearsome imagery of its liturgical origin. To understand the significance of the Dies irae in the music of Williams, then, we must return to its source: the text of the Gregorian hymn.

The words of the Dies irae, usually attributed to the thirteenth century Italian monk Thomas of Celano, conjure a vision of the apocalypse as a “Day of wrath and doom impending” at the dawn of which the dead rise from their tombs to answer for their sins (stanza IV):

Death is struck, and nature quaking,

All creation is awaking,

To its Judge an answer making.

The resurrection of the dead inaugurates a cosmic courtroom drama over which God presides as a stern judge prepared to punish every transgression (stanza VI):

When the Judge his seat attaineth,

And each hidden deed arraigneth,

Nothing unavenged remaineth.

Central to the original meaning of the Dies irae is the idea of guilt (stanza XII):

Guilty, now I pour my moaning

All my shame with anguish owning

Spare, O God, Thy suppliant groaning!a

a. 1849 translation by William Josiah Irons, published in the 1912 English missal. Available online at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dies_Irae_(Irons,_1912).

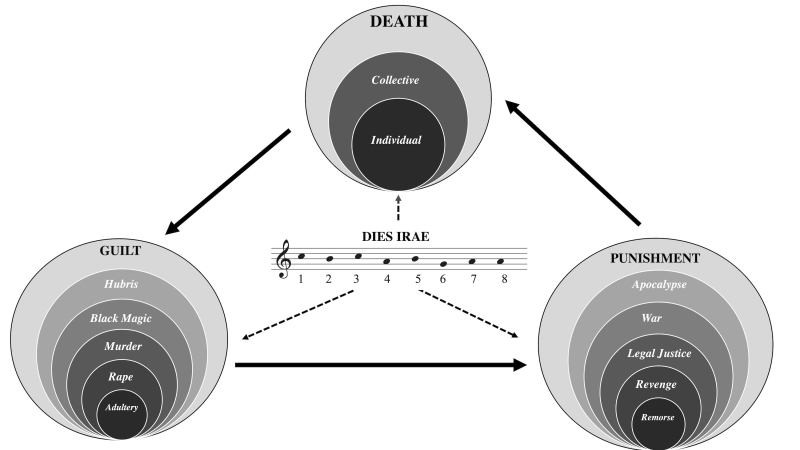

To listeners familiar with this text, the melodic line of the Dies irae - even in purely instrumental settings—has the potential to suggest at least three interconnected concepts: DEATH, GUILT, and PUNISHMENT (Figure 11). Each of these general concepts is instantiated by specific manifestations. DEATH encompasses both individual and collective demise; GUILT is exemplified by moral transgressions including adultery, rape, murder, black magic, and hubris; while PUNISHMENT can range from the emotional torment of private remorse to extrajudicial revenge, state-sanctioned legal retribution, the deprivations of war, and apocalypse. To what extent the meaning of a piece of film music that appears to allude to the Dies irae can be plausibly associated with any of these terms depends, again, on the context provided by the specific dramatic situation it accompanies.

Figure 11

Concepts associated with the Dies irae.

In the following analyses, I will situate John Williams’s invocation of the Dies irae within the conceptual triangle depicted in Figure 11. As we will see, Williams tends to invoke the Dies irae in films that explore the causal link between GUILT, PUNISHMENT, and DEATH. The resulting conceptual overlap causes the Dies irae to resonate with all three domains in ways that amplify the fundamental ethical dilemma at the heart of each of the films in which it is used, regardless of whether this dilemma unfolds on the individual level of interpersonal relationships (as in Presumed Innocent, Alan J. Pakula, 1990), or whether it involves collective catastrophes of a global or intergalactic scope (as in War of the Worlds and Revenge of the Sith). Williams’s frequent invocations of the Dies irae—one of the few historic musical memes that is widely recognized in our increasingly atomized musical culture—add a universalizing, mythical dimension to the narratives they accompany.

“When the Judge his seat attaineth”: the Dies irae as a signifier of guilt and revenge in legal thrillers

Presumed Innocent (1990)

Considering that the text of the Dies irae describes a metaphysical trial, it is fitting that Williams alludes to the chant melody in Presumed Innocent and Sleepers, two legal thrillers in which the nexus of GUILT and PUNISHMENT is reflected in a secular microcosm. Presumed Innocent explores the tension between legal culpability and private guilt; it demonstrates how the unexpected consequences of our actions can spin out of control, with potentially devastating consequences. The film begins with the image of an empty courtroom. In a voiceover, we hear the main character, prosecutor Rusty Sabitch, reflect on the process by which guilt and innocence are determined within the framework of the legal system:

I’m a prosecutor. I’m part of the business of accusing, judging, and punishing. I explore the evidence of a crime and determine who is charged, who is brought to this room to be tried before his peers. I present my evidence to the jury and they deliberate upon it. They must determine what really happened. If they cannot, we will not know whether the accused deserves to be freed or should be punished. If they cannot find the truth, what is our hope of justice?

The central irony of the film hinges on the fact that Rusty Sabitch, charged with punishing the transgressions of others, turns out to be fallible himself and becomes entangled in the mechanisms of the law he strives to enforce. The transgression that sets the plot in motion is Rusty’s adulterous affair with his colleague Carolyn. When his emotionally instable wife Barbara discovers that he has been unfaithful, she hatches a plot to punish both her husband and her rival by murdering Carolyn and arranging the evidence to point to Rusty as the perpetrator. Rusty is arrested, but narrowly escapes conviction. Not until after his acquittal does he discover that Carolyn’s killer was his own wife, driven by jealousy to insanity and murder. He is left tormented by remorse for the catastrophic consequences of his infidelity. The film concludes as it began, with an image of an empty courtroom, over which we hear Rusty’s voice describing his existence as a kind of purgatory:

I am a prosecutor. I have spent my life in the assignment of blame. With all deliberation and intent, I reached for Carolyn. I cannot pretend it was an accident. I reached for Carolyn and set off that insane mix of rage and lunacy that led one human being to kill another. There was a crime. There was a victim. And there is punishment.

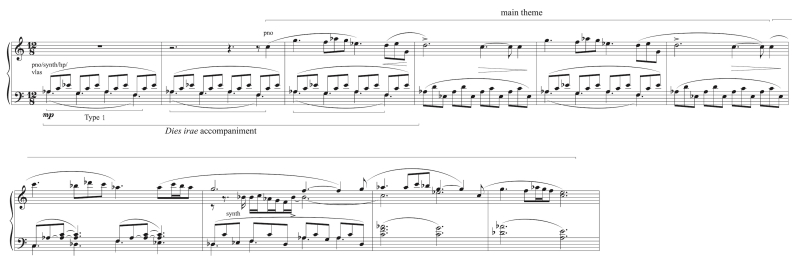

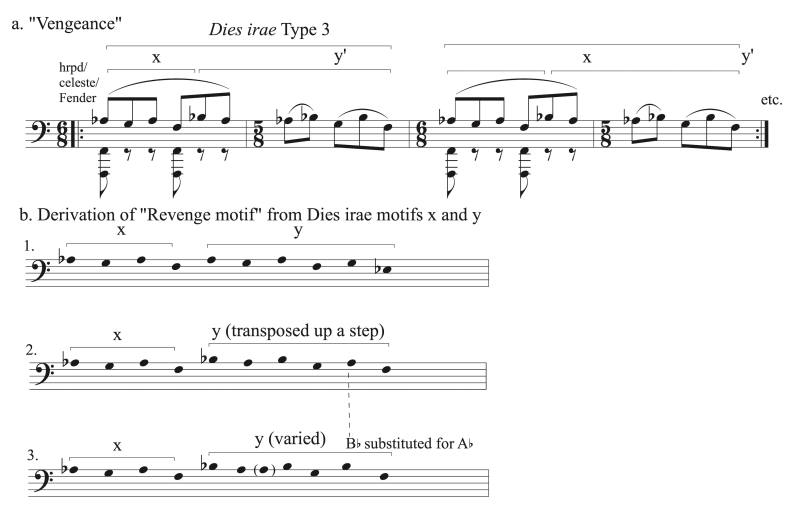

Crime, victim, punishment—all three are suggested in the Dies irae Type 1 ostinato pattern which accompanies the main theme of the film, a melancholy cantilena that pervades the score and is first heard in the opening credits (Figure 12; Clip 12). The placement of the Dies irae in the bass constitutes the foundation of the counterpoint between the tormented melodic line (with its reiterated, anguished tritone appoggiatura) and thus metaphorically expresses an obsession rooted in guilt.

Figure 12

Presumed Innocent, “Main Title,” personal transcription.

Clip 12

Presumed Innocent, “Main Title.”

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357697

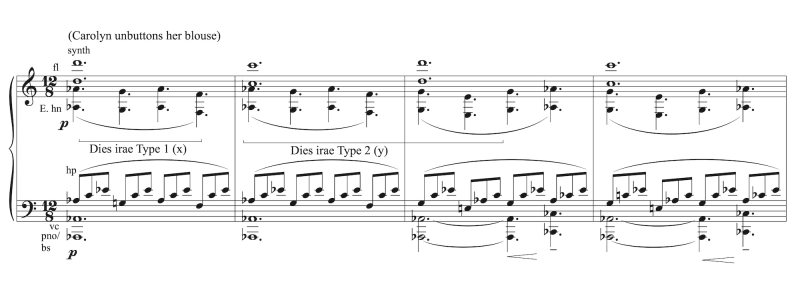

Williams uses the Dies irae to underscore the causal link between two key junctures of the narrative, beginning with Carolyn’s seduction of Rusty. Having lured Rusty into her office, Carolyn unbuttons her blouse. Williams punctuates this gesture, which marks the fateful moment their relationship crosses the boundary from flirtation to adultery, with a sensuous but sinister statement of motif x—thereby linking the Dies irae with the forbidden sexuality of the “original sin” that sets the plot in motion (Figure 13; Clip 13). As we will see in the case of Attack of the Clones and Jurassic Park, this is not the only situation involving the crossing of literal and figurative boundaries that Williams punctuates with a Dies irae.

Figure 13

Presumed Innocent, “Love Scene,” personal transcription.

Clip 13

Presumed Innocent, “Love Scene.”

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357727

As Rusty succumbs to temptation, he has no idea that his transgression is the first step in a chain of events that will culminate in Carolyn’s death and his own arrest for murder. But the music, like a Greek chorus, prophesies doom—a prophecy that is fulfilled when months later, Rusty is hauled in handcuffs to a police car, once again to the somber accompaniment of the Dies irae10 (Figure 14; Clip 14). The motivic parallelism between the two scenes connects cause and effect, Rusty’s original sin and his eventual fall from grace. Williams’s choice of the Dies irae as a key motif in Presumed Innocent resonates simultaneously with Carolyn’s death, Rusty’s guilt, and his punishment for a crime he did not commit but for which he feels responsible. With characteristic elegance and sophistication, the composer distills the essential elements of the plot into a four-note ostinato.11

Figure 14

Presumed Innocent, “On the Advice of Counsel” (original version—first 6 measures not used in film), personal transcription.

Clip 14

Presumed Innocent, “On the Advice of Counsel” (original version—first 6 measures not used in film).

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357771

Sleepers (1996)

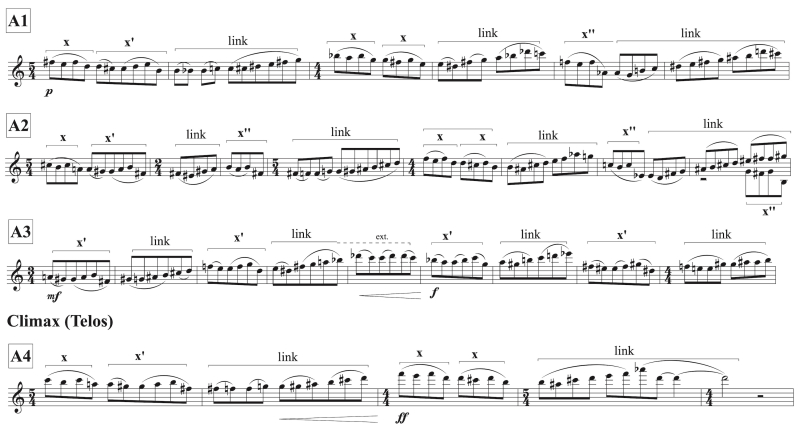

In Sleepers, another courtroom drama that explores the unintended but progressively more devastating consequences of an initial transgression, the Dies irae is associated specifically with the concept of revenge. Set in New York City, the film centers on four boys who steal a hot-dog cart as a prank. After the prank goes disastrously wrong, they are sentenced to juvenile prison, where they are subjected to violence and sexual abuse at the hands of sadistic prison guards. After their release, the boys are left psychologically scarred. Twenty years later the opportunity presents itself to take revenge, and the four friends pursue both legal and illegal means of punishing their former tormentors. Their obsessive quest for payback culminates in the vigilante murder of two of the guards and the arrest of another.

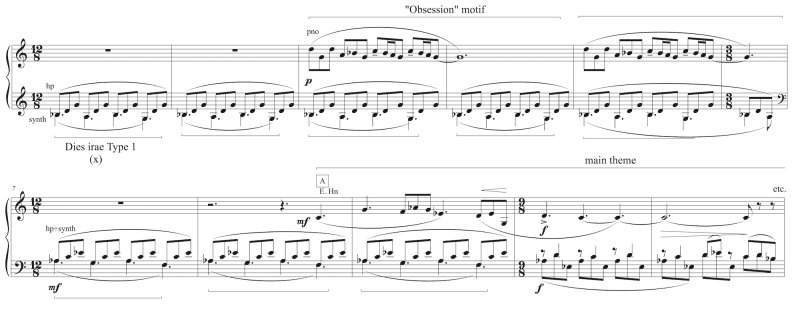

“Revenge. Sweet lasting revenge […] Now it’s time for all of us to get a taste,” observes Michael (the intellectual among them, whose favorite book is Alexandre Dumas’ revenge thriller The Count of Monte Cristo). Williams expresses the desire for retribution that motivates Michael and his friends through the “Vengeance” motif, a restless, circular, metrically unbalanced ostinato figure based on a Type 3 Dies irae (Figure 15a; Clip 15) which accompanies the planning and execution of the complex scheme devised by Michael to hunt down their enemies. The culmination of the “Vengeance” motif occurs in a cue titled “Revenge for Rizzo” in which the former guard Henry Addison is shot by gangsters in the marshes surrounding LaGuardia Airport. As bullets riddle Addison’s body, the relentless, Dies irae-saturated ostinato chillingly invokes the line “Nothing unavenged remaineth” from stanza VI of the medieval hymn.

Figure 15

Sleepers, vengeance motif, personal transcription.

Clip 15

Sleepers, vengeance motif.

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357865

The way Williams derives “Vengeance” from the Dies irae is characteristic of his often complex approach to motivic transformation12—as illustrated in Figure 15b, the motif is based on segments x and y of the Dies irae (b1), with segment y transposed up a step (b2) and subjected to variation through the repetition and substitution of pitches (b3). Not only is the motif internally repetitive, it appears invariably as a repeating loop. This emphasis on incessant repetition (unusual for Williams, who tends to avoid prolonged stasis) encapsulates the experience of trauma that lies at the heart of the film. As Slavoj Žižek notes, “there is an inherent link between the notions of trauma and repetition […] a trauma is by definition something one is not able to remember, i.e. to recollect by way of making it part of one’s symbolic narrative; as such, it repeats itself indefinitely, returning to haunt the subject” (Žižek [2001] 2003, 36–37).

“See fulfilled the prophet’s warning”: foreshadowing in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977)

A particularly complex example of the Williams Dies irae as a signifier of death and retribution occurs in Star Wars: A New Hope. The composer’s original but unrealized plan involved a sophisticated strategy of motivic foreshadowing that was intended to begin with the iconic binary sunset scene. Uncle Owen has prohibited Luke from leaving home, thereby thwarting Luke’s ambitions of becoming a space pilot. Frustrated and disappointed, the young man steps outside to watch the twin suns of his home planet Tatooine set over the desert. He longingly gazes at the celestial bodies, which represent to him all the allure of the distant galaxies he aspires to explore. At this stage, Luke can only dream about adventure; trapped by familial expectations, he lacks the resolve to defy his uncle’s expectations.

Williams original cue for this scene, which was rejected by George Lucas, was constructed around a Type 1 Dies irae accompaniment (Figure 16; Clip 16). This motivic choice foreshadows not only the imminent massacre of Luke’s family, but also the ensuing desire for retribution that sets Luke on the path to fulfilling his destiny as a Jedi knight: a destiny that will culminate in the destruction of the death star and the ultimate collapse of Darth Vader’s power. The use of the Dies irae in the original version thus imbues the scene with a darker tone than the revision, which features a lyrical statement of the Force theme.

Figure 16

Star Wars: A New Hope, original unused version of “Binary Sunset,” personal transcription.

Clip 16

Star Wars: A New Hope, original unused version of “Binary Sunset.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / 20th Century Fox / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357929

The next day, Luke visits the mysterious desert hermit Obi Wan-Kenobi. Obi Wan implores the young man to join him on the quest to free Princess Leia from the clutches of Darth Vader but Luke refuses, citing the need to help his uncle gather the harvest on their farm. Luke’s “refusal of the call,” as Joseph Campbell terms this stage of the archetypal hero’s journey (Campbell [1949] 2008, 49), is punctuated musically by another reference to the Dies irae—a second foreshadowing of impending calamity (Figure 17; Clip 17).

Figure 17

Star Wars: A New Hope, “Tales of a Jedi Knight/Learn about the Force,” personal transcription.

Clip 17

Star Wars: A New Hope, “Tales of a Jedi Knight/Learn about the Force.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / 20th Century Fox / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357913

Let’s turn now from these ominous musical premonitions to the catastrophe they prophecy: Luke’s discovery that in his absence imperial stormtroopers have burned down the farm and killed his aunt and uncle. This traumatic juncture brutally untethers Luke from the domestic and familial responsibilities that have encumbered him until now. Loss liberates him; the desire to join the struggle against those who murdered his family provides Luke with the motivation to stop dreaming and start acting.13 In the screenplay, Lucas explicitly articulates Luke’s emotions: “hate replaces fear and a new resolve comes over him,” a point emphasized in the music by the climactic statement of a Type 1 Dies irae in the horns that accompanies his paroxysm of “hate” and “resolve” (Figure 18b, last system; Clip 18). This crucial moment is carefully prepared by the preceding section of the cue, which first develops a propulsive four-note motif based on the inverted Dies irae (Type 5, Figure 18a) that is then contrapuntally interwoven with a searing statement of the Force theme (Figure 18b, first system).14 The thematic combination points the way to Luke’s future, in which joining the Jedi will give him the powers he needs to avenge the death of Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru. As Dan Golding puts it,

[The Dies irae] serves as a musical sign both of death and of providence, set against Williams’ major spiritual melody of the series in “the force theme.” There is a sense that the world of Star Wars shifts on the playing of this music; it is the moment when the story becomes about Skywalker. (Golding 2019, 126)

Figure 18

Star Wars: A New Hope, “Burning Homestead,” personal transcription.

Clip 18

Star Wars: A New Hope, “Burning Homestead.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / 20th Century Fox / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357358

“Doomed to flames of woe unbounded”: revenge, hubris, and transformation in the Star Wars prequels and sequels

Attack of the Clones (2002)

While Luke eventually learns from Obi-Wan and Yoda to master his anger, his father Anakin succumbs to the dark side. His excessive pride and need for control mark him as an anti-hero in the tradition of Greek tragedy, and as a mortal sinner in the Christian framework invoked by the Dies irae.15 Pride belongs to the conceptual domain of GUILT. It is a sin for which Anakin will literally burn in Revenge of the Sith—“doomed to flames of woe unbounded,” as stanza XVI of the Dies irae puts it.

Anakin’s corruption begins in Attack of the Clones. “The thought of not being with you […] I can’t breathe,” he confesses to Padmé as the two sit by the fireplace in her palace on Naboo—an early indication of his boundless urge not just to protect, but to possess and control, those he loves. As he expresses his passion in terms that are obsessive in their intensity (“I’m haunted by the kiss that you should never have given me. My heart is beating... hoping that kiss will not become a scar. You are in my very soul, tormenting me…”), a restless string line based on motif x of the Dies irae stirs in the orchestra. It is sequentially transposed upward before settling on the pattern F-E-F-D-G-D in the viola, echoed by the flute and horn—a fragmentary Type 3 Dies irae (F-E-F-D-G-[E-F]-D). Like “Binary Sunset,” these subtle hints at the Dies irae will turn out to be prophetic: Anakin’s eventual downfall is rooted in his love for Padmé and his willingness to do anything—even join the Dark Side—to avoid losing her (Figure 19; Clip 19).

Figure 19

Attack of the Clones, evolution from motif x to fragmentary Type 3 Dies irae in “Anakin and Padmé,” personal transcription.

Clip 19

Attack of the Clones, evolution from motif x to fragmentary Type 3 Dies irae in “Anakin and Padmé.”

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357414

After his mother is abducted and mortally wounded by Tusken Raiders on Tatooine, Anakin slaughters an entire village in a blind fury of revenge. As he confides to Padmé shortly after the massacre,

I killed them all. They’re dead, every single one of them… Not just the men. The women and children too. They’re like animals, and I slaughtered them like animals.

Tormented by his failure to save his mother, Anakin vows to Padmé that he will overcome death itself: “I will be the most powerful Jedi ever […] I will even learn to stop people from dying.” His bloody vengeance and arrogant refusal to accept the limits of mortality marks the beginning of his turn to the dark side. This juncture in the narrative is accompanied by a fully-fledged Type 3 Dies irae ostinato (Figure 20a; Clip 20), and marks the completion of the motivic crystallization that took place during the fireplace confession on Naboo (Figure 20b). Williams’s use of the Dies irae as an ostinato that circles obsessively through most of the cue establishes an obviously relevant intertextual link with the “Vengeance” motif from Sleepers (Figure 15).16 Note the diabolical tritone in the bass that signals the “dark side” of the Force.

Figure 20

Attack of the Clones, complete Type 3 Dies irae in “Anakin Changes,” personal transcription.

Clip 20

Attack of the Clones, complete Type 3 Dies irae in “Anakin Changes.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357458

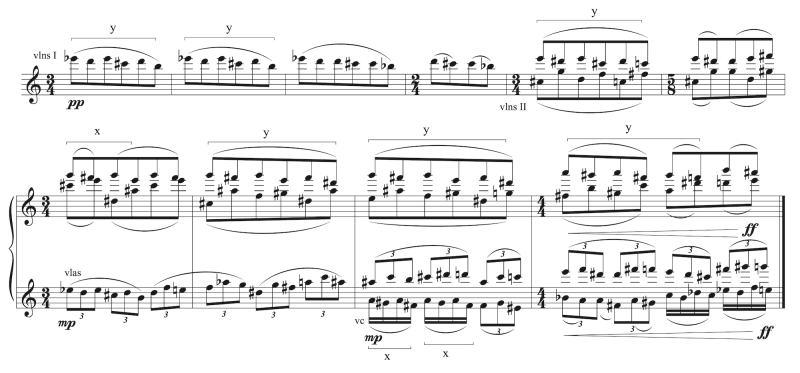

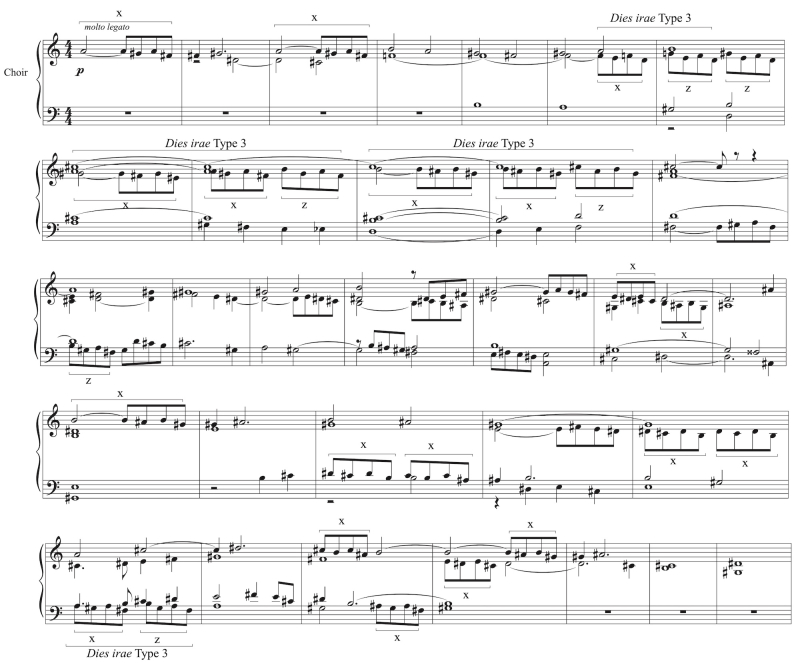

Revenge of the Sith (2005)

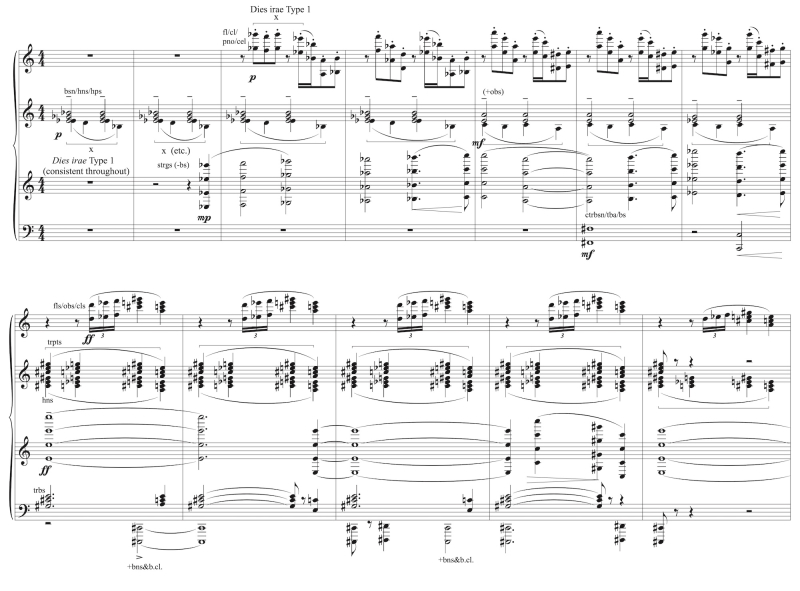

Having introduced a motivic fragment derived from the Dies irae in Attack of the Clones, Williams subjects it in Revenge of the Sith to another process of transformation that culminates in a climactic musical point of arrival: “Lament” (Figure 21; Clip 21), a requiem for the Republic that interweaves three different types of Williams Dies irae (1, 3, and 4). This apotheosis of the Dies irae, which fuses a number of relevant semantic associations (revenge, death, grief, apocalypse) accompanies an extended montage of clone troopers assassinating Jedi generals across the galaxy at the command of Palpatine (the infamous “Order 66”).

Figure 21

Revenge of the Sith, three types of Williams Dies irae in “Lament,” personal transcription.

Clip 21

Revenge of the Sith, three types of Williams Dies irae in “Lament.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357432

The overt deployment of the Dies irae in “Lament” is, again, subtly anticipated earlier in the film by the “Sith Seduction” motif, an orchestral shiver based on a Type 6 Dies irae (the retrograde of its first four notes). Introduced twenty minutes before the Order 66 montage, the “Sith Seduction” motif underscores Anakin’s discovery that Palpatine is a Dark Lord of the Sith (Figure 22a; Clip 22). In the ensuing confrontation, Palpatine cunningly manipulates Anakin by using the young Jedi’s rage and confusion as a gateway into the dark side of the Force (“I can feel your anger. It makes you stronger, gives you focus”). As Anakin falls under the spell of evil, the backward Dies irae of the “Sith Seduction” motif solidifies into the angular bass line that underpins his murder of the Separatist leaders on Mustafar (Figure 22b).17 This association of the Dies irae with the demonic evil of the Dark Side taps into another deep semantic tributary: the ghoulish and gothic aspects that were first exploited by Romantic composers such as Berlioz and Liszt, and continue to reverberate in countless film scores (including the “Ave Satani” from Goldsmith’s The Omen, which, as mentioned above, is also based on a Dies irae retrograde).

Figure 22

Revenge of the Sith, “Sith Seduction” in “Palpatine’s Seduction” and bass line derivative in “Anakin’s Dark Deeds,” personal transcription.

Clip 22

Revenge of the Sith, “Sith Seduction” in “Palpatine’s Seduction” and bass line derivative in “Anakin’s Dark Deeds.”

Crédits: © Lucasfilm / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357485

The Dies irae that underpins Palpatine’s cunning manipulations and the triumph of his evil plan to overthrow the Jedi also insinuates itself into the musical DNA of his granddaughter Rey (Figure 23; Clip 23). But in her music, it appears transmuted into a luminous chimes motif that reflects her noble character and the disavowal of her Sith heritage: a semantic inversion which indicates that through Rey, the destruction of the Jedi wrought by Palpatine will be avenged, that the Sith will, in effect, be beaten with their own weapons.

Figure 23

Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015), “Rey’s Theme,” personal transcription.

Clip 23

The Force Awakens, “Rey’s Theme.”

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357496

In this sense, Rey, the granddaughter of Palpatine/Sidious, is a reincarnation of Luke, the son of Anakin/Vader: both are scions of an evil stock who renounce, and ultimately defeat, the dark side. The link between Luke and Rey is made explicit by the recycling of “Burning Homestead” from A New Hope during the climax of The Force Awakens. As Rey draws her light saber to confront Kylo Ren in the forest duel, Williams recapitulates the concluding section of “Burning Homestead” (Figure 18). The result, as Dan Golding notes, is a complex mirror-within-a mirror nesting of referential meaning:

[T]he direct reuse of the “Burning Homestead” cue, including the “Dies irae” quotation, reveals multiple levels of meaning making through repetition…Here, we can see at least three forms of citation going on: a citation of the “embrace of the call” heroic narrative moment between generations of Star Wars heroes, as Luke and Rey accept their place in the larger world; a citation of the Williams composition that is repeated across both scenes; and a citation of this specific “Dies irae” invocation, and also the centuries-old tradition of the “Dies irae” along with it. (Golding 2019, 127)

Williams’s variations on the Dies irae in the Star Wars series are extraordinary in their structural and expressive range. Whether through straightforward statements of its first four notes or through sequential expansion, inversion, or retrograde, the venerable trope enriches the meaning of a wide range of dramatic situations - from the individual level of Luke and Anakin’s desire for revenge to the intergalactic tragedy of Order 66. The latter use of the motif—as a signifier of collective catastrophe—is, of course, closest to the original apocalyptic meaning of the medieval hymn, and it is in this semantic domain that Williams has created some of his most indelible adaptations of the Dies irae.

“Heaven and earth in ashes ending”: the Dies irae as a signifier of Apocalypse in Empire of the Sun, War of the Worlds, Jurassic Park, and A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Williams’s music for films dealing with an actual or potential apocalypse can be divided into two categories: “invasion narratives” in which a ruthless enemy destroys civilization (the Japanese in Empire of the Sun, the Martians in War of the Worlds) and “Frankenstein narratives” in which humanity risks self-extermination through the creation of artificial beings that compete for survival (resurrected dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, sentient robots in A.I. Artificial Intelligence). In all of these films, the Dies irae assumes a universal significance that invites the viewer to reflect on the fate of our species as a whole.

Empire of the Sun (1987)

Empire of the Sun, set in Shanghai during the Japanese invasion of China in World War II, lays bare the fragile boundary that separates civilization from chaos. Jim, a spoiled, upper middle class British schoolboy, grows up in a luxurious villa and lives a pampered life. His privileged existence is exemplified by an early scene in which he rummages through the fridge (lavishly stocked with meats and sweets) for a late-night snack, to the consternation of his Chinese servant. “You have to do what I say,” Jim insists as he orders the servant to give him butter biscuits—a command that “expresses colonialism [and] the ethos of his society,” as screenwriter Tom Stoppard notes (Stalcup 2013, 256). Spielberg establishes a sharp contrast between the sheltered life of the European community in the Shanghai International Settlement and the harsh reality outside its walled compounds, with its beggars, seething crowds of impoverished Chinese, and the escalating threat posed by Japanese troops.

When war breaks out, Jim’s idyllic existence is turned upside down. During the chaotic evacuation of the city, he is separated from his parents. Eventually, he makes his way back to his home in hopes of reuniting with them, but the house is deserted. In an echo of the earlier kitchen scene, Jim pokes around in the fridge, but now finds only rotten, moldering remains (sic transit gloria mundi). In his mother’s destroyed bedroom, he discovers the imprints of her bare feet and hands, mingled with those of boots, in the talcum powder spilling from her dresser: signs of a violent struggle in which she was attacked, and—for all Jim knows—killed by Japanese soldiers. He rushes to the window and opens it, the wind erasing the last traces of his mother’s agony in a poignant image of ephemerality. As Jim descends the stairs, he encounters the servant in the process of absconding with furniture. When he confronts her, she slaps him - an act of reprisal for his earlier insolence that encapsulates the reversal of Jim’s fortune from pampered princeling to scorned street urchin. In the next scenes, we see Jim riding his bike through the abandoned house and wandering about the desolate garden as autumn leaves drift into the drained swimming pool. In these haunting images, Jim is depicted as the last survivor of an apocalypse, roaming the crumbling ruins of a dead civilization.

The end of Jim’s sheltered life and the collapse of the established order is symbolized by the servant’s slap—a charged gesture which, in a more general sense, represents punishment for the sins of colonialism. His subsequent odyssey through the wastelands of war and prison camp is a kind of purgatory in which he is purged of indolence, arrogance, and inherited privilege. In this context, Williams’s invocation of the Dies irae in the cues that accompany Jim’s return to his deserted home (“Alone at Home,” “The Empty Swimming Pool”) is rich in symbolic meaning.

The music for this sequence (Figure 24; Clip 24) is an example of what could be called the Apocalypse trope18 in Williams’s work—an eerie texture of two or more chromatically meandering melodic lines which entwine in dissonant polyphony, usually scored for strings in a high register and reminiscent both of the “Twisted Counterpoint” topic in horror film music (as exemplified by Bernard Herrmann’s “The Madhouse” from Psycho, Clip 25)19 and of certain works by Shostakovich (14th Symphony, first movement) and Khachaturian (the Adagio from the Gayane Suite No. 3 that was used in 2001: A Space Odyssey).20 As in the pieces by Shostakovich and Khachaturian, the motivic fabric of “Alone at Home” and “The Empty Swimming Pool” is permeated by references to the first phrase of the Dies irae (similar examples appear in War of the Worlds and A.I. Artificial Intelligence). In all of these cases, the “Dies irae” and “Twisted Counterpoint” topics are fused and thus absorbed into the larger Apocalypse trope.

The way Williams unveils the Dies irae in “Alone at Home” exemplifies a structural method characteristic of the composer. The hushed dynamics, high tessitura, and absence of low frequencies in “Alone at Home” create a sense of glazed fragility that suggests a state of shock. As Jim ascends the stairs from the kitchen and enters his mother’s bedroom, the Dies irae emerges from the steady stream of eighth notes through the gradual, almost imperceptible, concatenation of its constituent pitches. At the beginning of the cue, Williams only hints at the Dies irae by stating the first 3 notes; in measure 10, he adds the fourth note; in measure 13, he adds the fifth note; it takes until measure 19 before the six-note phrase of motif y in D minor comes into focus as Jim approaches his mother’s dresser. The first phrase of the Dies irae has now almost fully emerged and is stated again in measure 28, as Jim realizes what the footprints in the powder signify. This process of teleological genesis, by which an extended melodic idea crystallizes gradually from shorter motivic fragments21, is applied here to the local level of an individual cue, but it is also frequently used by Williams to provide structural coherence to the large-scale architecture of a score (for an in-depth discussion of teleological genesis in E.T. and Close Encounters, see Schneller 2014).

Figure 24

Empire of the Sun, teleological genesis in “Alone at Home,” personal transcription.

Clip 24

Empire of the Sun, teleological genesis in “Alone at Home.”

Crédits: © Warner Bros. / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357230

War of the Worlds (2005)

There is a parallel scene in another harrowing “invasion narrative” directed by Steven Spielberg. In Empire of the Sun, a boy gazes at the aftermath of violence in a bedroom destroyed by Japanese soldiers; in War of the Worlds, it is a girl who gazes at a river filled with the bodies of people murdered by alien invaders. Both are visions of apocalyptic horror that mark the traumatic immolation of childhood innocence in the fires of war: a connection made explicit by the musical accompaniment, which in both cases is based on the first six notes of the Dies irae (Figure 25; Clip 31). In War of the Worlds, the gradual proliferation of voices from a single line to dense 4-part polyrhythmic counterpoint mirrors the proliferation of the bodies floating by in the water: first one, then another, finally dozens.

Figure 25

War of the Worlds, “Bodies in the River,” personal transcription.

Clip 31

War of the Worlds, “Bodies in the River.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357398

The Dies irae is a particularly apt point of reference for the river scene in War of the Worlds. Its imagery recalls the Black Death in 1348, when the Rhône River in Avignon was clogged with the corpses of plague victims—a disaster widely believed to have been caused by an angry God to punish the world for its sins (Kennedy 2023, 92–93). In War of the Worlds, it is the aliens who appear God-like in their omniscient powers of observation, their superior intelligence, and their overwhelming might, as the opening voice-over indicates:

No one would have believed in the early years of the twenty-first century, that our world was being watched by intelligences greater than our own. That as men busied themselves about their various concerns, they observed and studied, like the way a man with a microscope might scrutinize the creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro about the globe, confident of our empire over this world. Yet, across the gulf of space, intellects, vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded our planet with envious eyes, and slowly and surely, drew their plans against us.

The key phrase here is “infinite complacency,” which suggests a decadent civilization focused on trivial matters. Both Empire of the Sun and War of the Worlds center on flawed protagonists who reflect the vices of their respective societies and are subjected, through the brutal intervention of an external enemy, to a traumatic but ultimately therapeutic process of existential reassessment. As a stand-in for humanity, Ray, the (anti-)hero of War of the Worlds, is initially portrayed as negligent, irresponsible, and self-absorbed. Estranged from his divorced ex-wife and kids, he is an unsympathetic figure, a deadbeat dad who compensates for his lacking authority with bluster. The invasion by hostile alien forces provides a trial by fire which he survives by proving himself as a father who can protect his daughter in the face of peril; like Jim in Empire of the Sun, he undergoes a process of maturation. In both films, the arduous moral journey of the protagonists is rewarded through the ultimate defeat of the enemy (the bomb over Nagasaki, the microbes that kill the Martians) and their reunion with family (Jim with his parents, Ray with his son and ex-wife).

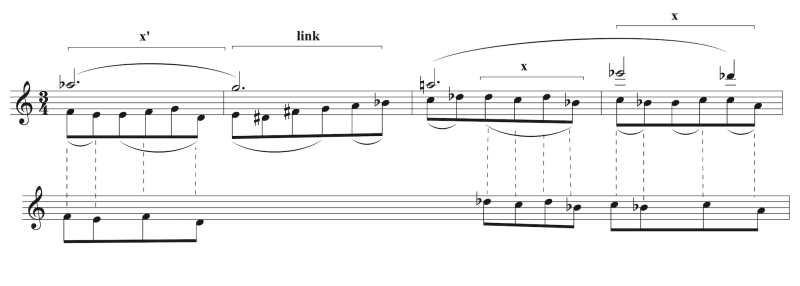

As in Empire of the Sun, Williams subjects the Dies irae to teleological genesis, but here the process plays out across multiple cues. A detailed analysis of the motivic evolution is beyond the scope of this article, so a summary of its principal stages will have to suffice. Following its spectacular first presentation as a chromatically compressed Type 2 in the river scene (Figure 25), the Dies irae resurfaces prominently in “Woods Walk,” which accompanies Ray and his children as they join a stream of refugees wandering across the desolate countryside. In this cue, Williams introduces two versions of motif x as well as an ascending link (Figure 26; Clip 32)—three motivic cells that, reordered and expanded through sequential transposition and development, will find their definitive expression in the “Epilogue” that accompanies the end credits.

Figure 26

War of the Worlds, “Woods Walk,” personal transcription.

Clip 32

War of the Worlds, “Woods Walk.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357330

In addition to moments of horror and desolation, the Dies irae marks pivotal points of separation and reunion. We hear it when Ray’s son Robbie leaves his father and sister to join the army (Figure 27; Clip 33), and again when Ray returns Rachel to her mother and reunites with Robbie.

Figure 27

War of the Worlds, “Robbie Joins the Fight,” personal transcription.

Clip 33

War of the Worlds, “Robbie Joins the Fight.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357258

The reunion scene begins as Ray carries Rachel through an autumnal Boston street. As they approach the family home, a solo horn intones an elegiac melody that combines motifs x and x’ from “Woods Walk” into a Type 4 Dies irae which serves as the antecedent of a somber but serene period in the Dorian mode (Figure 28; Clip 34). The emergence of this extended theme in a score which until now has been almost entirely textural presents a major structural moment, as does the harmonic transition to diatonicism from the dense chromatic dissonance that dominates the rest of the score. The fact that the reunion theme’s bittersweet lyricism springs from the same motivic source as the music for the horrors of the river scene and the desolation of the refugees in “Woods Walk” poignantly expresses Ray’s character arc. Suffering has taught Ray to be a better person; only through confronting death and deprivation is he able to progress from deadbeat dad to paternal protector. By weaving the Dies irae into the music for the climactic reunion, Williams points to the root cause of Ray’s personal transformation, while simultaneously acknowledging the collective catastrophe that has befallen humankind.

Figure 28

War of the Worlds, “Boston Street Finale,” personal transcription.

Clip 34

War of the Worlds, “Boston Street Finale.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357790

The theme that emerges in the reunion scene fuses the principal motivic strands of the Dies irae into a cohesive melodic statement and thus marks a significant point of arrival—but it is not quite the end of the process. As in his score for Close Encounters, where the apotheosis of the “Communication motif” unfolds over the closing credits (see Schneller 2014, 121), Williams reserves the actual telos of the Dies irae in War of the Worlds for the end title (“Epilogue”). The music unfolds in the harmonic twilight zone of octatonic/hexatonic/harmonic minor pitch fields that is a characteristic of the Apocalypse trope in Williams. Melodically, the “Epilogue” presents a mournful rumination on the end of the world in which the first phrase of the theme presented in “Boston Street Finale” (a Type 4 Dies irae) is subjected to an extended development that culminates in an impassioned climax—the telos of the score as a whole (Figure 29; Clip 35). We can trace a clear line of motivic evolution from “Woods Walk,” which provides the three principal motivic building blocks of the “Epilogue” via “Boston Street Finale”, which synthesizes x and x’ into the opening phrase of a new theme, to the climax of the “Epilogue” in which all of these elements are brought to ultimate fruition.

Figure 29

War of the Worlds, “Epilogue” (principal melodic line only), personal transcription.

Clip 35

War of the Worlds, “Epilogue” (principal melodic line only).

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357823

Jurassic Park (1993)

If the “Invasion narratives” of Empire of the Sun and War of the Worlds present an external enemy who destroys civilization from the outside, the “Frankenstein narratives” of Jurassic Park and A.I. Artificial Intelligence involve an internal threat that results from scientific and technological innovations gone rogue. Like Anakin, who attempts to conquer death by embracing the black magic of the Sith, John Hammond in Jurassic Park challenges the limits of mortality by turning to the technological wizardry of genetic engineering to resurrect long-extinct creatures. Hammond’s original sin is hubris: tampering with evolution through the manipulation of dinosaur DNA violates the natural and temporal order. Early in the film, the irresponsibility of this transgression is articulated by Dr. Malcolm:

[T]he lack of humility before nature that’s being displayed here […] staggers me […]. Don’t you see the danger, John, inherent in what you’re doing here? Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that’s found his dad’s gun.

Malcolm is proven right when the resurrected dinosaurs break through the fences of the park and become an uncontrollable force of destruction. The broken fence is thus the key visual metaphor of Jurassic Park. It captures Hammond’s central moral transgression—the violation of ethical boundaries in the pursuit of profit and technology. Fences embody the concept of boundaries that ought to be preserved and respected—the boundaries between humankind and nature, technology and evolution, the living present and the extinct past. Hammond’s breaching of these boundaries through genetic engineering is mirrored in its punishment: the T-Rex ripping through the fence that separates the domain of humans from that of dinosaurs.

The symbolic significance of fences in Jurassic Park may explain why Williams chose the Dies irae as the basis for a musical motif that, as Mike Matessino has noted, is linked specifically with the visual motif of the electric fence (2022). We first hear the “fence motif” after Dr. Sattler discovers the breached fence through which the T-Rex escaped a few hours earlier (Figure 30a; Clip 36). The motif appears again as Dr. Grant and the children, who have been trapped in the dinosaur enclosure, scale the fence to get out (Figure 30b). The musical symmetry of the two scenes points to their inverted parallelism: the first scene shows the aftermath of a dinosaur breaching the fence to enter the human domain. In the second, it is humans who breach the fence to leave the dinosaur domain. Each scene involves the traversal of a literal and figurative boundary that should never have been crossed, a point made explicit in the music through Williams’s invocation of the Dies irae.22

Figure 30

Jurassic Park, “Fence” motif, personal transcription.

Clip 36

Jurassic Park, “Fence” motif.

Crédits: © Universal Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357379

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

As in Jurassic Park, the nexus of hubris and apocalypse is central to A.I. Artificial Intelligence. The film begins with an apocalyptic image: the roiling waters of the rising ocean that, due to human-induced climate change, has swallowed most of the planet—an obvious reference to the Book of Genesis, in which God punishes the sins of humanity with a flood. In A.I., man’s original sin is, once again, hubris. Hubris manifests itself in the destruction of the planet through industrial technology; hubris motivates Professor Hobby who, like Victor Frankenstein, challenges God by creating artificial life; and it is hubris that causes medical science to cheat mortality by preserving through cryonic suspension those who would otherwise have died (note, again, the link with Anakin). The refusal to live in harmony with nature and accept the limits it imposes on us brings about a global apocalypse. As a result, our species is doomed to extinction and leaves a world inhabited only by robots.

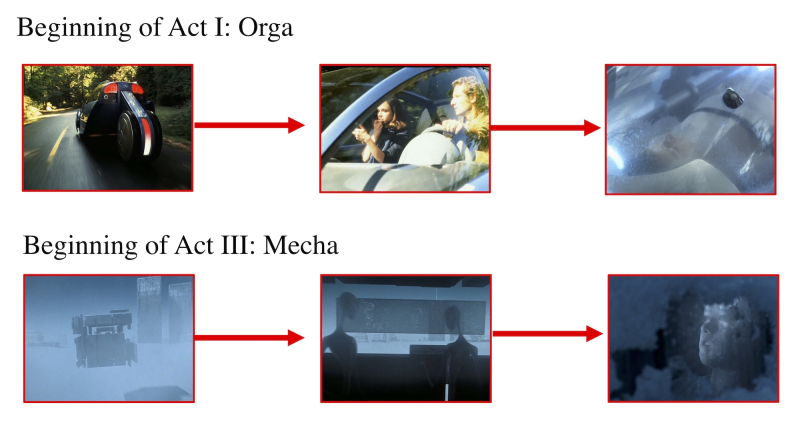

This eschatological trajectory is reflected in the symmetry between the opening of Act I and Act III. The visual structure of both sequences is identical: in Act I, the camera follows a moving vehicle through a forest. We see a glimpse of the passengers, a man and a woman. They arrive at their destination, a medical facility in which they visit a cryogenically frozen human boy in a capsule. At the beginning of Act III, the camera follows a moving aircraft through a frozen wasteland; we see a glimpse of the passengers, highly evolved robots; they arrive at their destination, an excavation site where they unearth a frozen robot boy in an amphibicopter. This visual rhyme throws into relief the evolutionary transformation from human to robot, orga to mecha, that unfolds over the course of the film (Figure 31).

Figure 31

Comparison of visual structure, Acts I and III, A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001).

The visual symmetry is emphasized by the music for the two scenes, which incorporates motifs x and z of the Dies irae. The first cue, a ruminative elegy for strings that presents yet another manifestation of the Apocalypse trope, is shot through with subtle allusions to the Dies irae that will only come to fruition in Act III (Figure 32; Clip 37).23 The music enters near the end of the preceding scene, in which Professor Hobby ponders the obligations humans have to their mechanical children by comparing robots to Adam and humans to God (yet another instance of the arrogance that will ultimately destroy humanity). The references to the Dies irae in the music that follows serve as an ominous, prophetic commentary on Hobby’s hubris: as humans have replaced God, the music seems to suggest, so one day robots will replace humans.24

Figure 32

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Cryogenics,” personal transcription.

Clip 37

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Cryogenics.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357296

The music for the parallel scene at the beginning of Act III is constructed from similar elements, namely, motifs x and z of the Dies irae, but now the monochromatic timbre of string orchestra is replaced by the monochromatic timbre of a cappella chorus (Figure 33; Clip 38). The wordless, unaccompanied human voice is, of course, a hauntingly ironic choice of timbre for a post-apocalyptic world in which nothing remains of humanity but a few crumbling skyscrapers and two frozen robots. In this requiem for our now extinct species, the fire and ashes of the Day of Wrath have cooled into an icy serenity.

Figure 33

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Journey Through the Ice,” personal transcription.

Clip 38

A.I. Artificial Intelligence,“Journey Through the Ice.”

Crédits: © Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks Pictures / Amblin Entertainment

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157357269

Conclusion

“As creatures we don’t know if we have a future,” Williams remarked in a 1997 interview, “but we certainly share a great past. We remember it, in language and in pre-language, and that’s where music lives—it’s to this area in our souls that it can speak” (Byrd 1997). The composer’s keen sensitivity to the semantic resonances of the musical past is evident not only in his many imaginative variations on the first phrase of the Dies irae, but also in its deployment as a musical commentary that highlights the moral crux of the narrative. As we have seen, in Williams’s oeuvre the Dies irae functions as a signifier of the distinct but overlapping concepts GUILT, PUNISHMENT, and DEATH. In Presumed Innocent, the Dies irae functions principally on an individual psychological level as a signifier of guilt, while in Sleepers, it is associated with an obsessive quest for revenge. In the Star Wars series, the Dies irae assumes a variety of meanings ranging from the foreshadowing of imminent doom to revenge, hubris, black magic, and grief, while in Empire of the Sun, War of the Worlds, Jurassic Park, and A.I., it is associated principally with the concept of apocalypse. In all of these scores, the Dies irae is carefully integrated into the overall motivic design, and in some cases subjected to a sophisticated process of teleological genesis on both the local and the large-scale level. Much, of course, remains to be said about the Williams Dies irae—in particular, its structural and semantic connections to the work of Rachmaninov and Goldsmith, its use as a red herring in Close Encounters and Home Alone, and its key importance in several other scores, including Story of a Woman and Black Sunday. But I hope the examples I have discussed in this article suffice to demonstrate that the Williams Dies irae is a prominent and semantically rich pattern in the complex tapestry of musical topics from which John Williams’s film music is woven.