This article examines and contextualizes John Williams’s significant engagement with the concept of childhood in his film music. Williams may be strongly associated with the “maximalism” of spectacle and adventure (Willman 2024),1 but in his intimate depictions of childhood, we can find some of his most memorable and dramatically consequential music. He has certainly had the opportunity to imbue musical life into a number of the most beloved child characters in the last half-century, such as Harry Potter, Elliott of E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982), and Kevin McCallister of Home Alone (Chris Columbus, 1990). Other children who have served as the main protagonist in Williams’s films include Jim of Empire of the Sun (Steven Spielberg, 1987), David of A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001), and Sophie of The BFG (Steven Spielberg, 2016). Besides these examples, other films scored by Williams use representations of childhood as a frame through which adult characters find meaning in their own lives: for example, Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), Hook (Steven Spielberg, 1991), Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993), The Patriot (Roland Emmerich, 2000), and Minority Report (Steven Spielberg, 2002).

Williams’s consistent engagement with this theme is partly due to his frequent collaborations with Steven Spielberg, who often crafts stories around the idea of childhood. Indeed, a recently published collection of essays (Schober and Olson 2016) examines this very concept in Spielberg’s films; however, despite Williams’s seemingly central role in conveying this important facet of Spielberg’s filmography, Schober and Olson’s collection contains only two passing references to Williams’s music. By exploring the close relationship between his music and this recurring thematic emphasis in the films Williams has scored, this article can thus provide further insight into this important aspect of Spielberg’s work. Its main purpose, however, is to highlight Williams’s role in idealizing a Romantic, idyllic notion of childhood, exploring the strategies he undertakes to do so.

Musical approaches to representing childhood in film: idyllic vs. fantastic

What does childhood sound like in film? Before delving into this question, two important qualifications are necessary to establish the framework of this paper. To begin, the focus here is on film music composed in the symphonic idiom of the Classical Hollywood revival that Williams operates in. Secondly, this paper considers musical representations of children or childlike feelings, rather than music for children. This distinguishes this study from such scholarship as Maloy (2020), which examines music written for child audiences, or McQuiston (2017), which discusses the score to Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, 2012) and its use of music “performed by, listened to, and even written by children” (2017, 483).2 It has a closer kinship with scholarship like Bottge (2006), which devotes some attention to exploring songs written about children in the nineteenth century.

Bourne (2024) frames childhood as a topic in film music. In doing so, she identifies a number of attributes we tend to observe in musical depictions of childhood on screen, including: major modes; high-register instrumentation (noting prominence of piano, music box, glockenspiel, etc.); singable, simple or “jumpy” melodies; sparse texture; syncopation; running 8th and 16th notes; and “playful” chromaticism (Bourne 2024, 93). To elaborate on Bourne’s description, we might divide the characteristics she identifies into two categories, using a framework devised by Ian Sharp (2000, 26–27): the first half shows a more tranquil, idealized childlike naivety, which Sharp deems the “idyllic approach” to representing childhood musically; the second half corresponds to a more playful, vigorous depiction of childhood, or the “fantastic dimension” (Table 1).

Table 1

|

Idyllic Childhood |

Fantastic Childhood |

| Major modes | Jumpy melodies |

| High-register instrumentation (ft. piano, glockenspiel, etc.) | Syncopation |

| Singable, simple melodies | Running 8th and 16th notes |

| Sparse texture | Sparse texture |

Childhood as a topic in film music, derived from Bourne (2024).

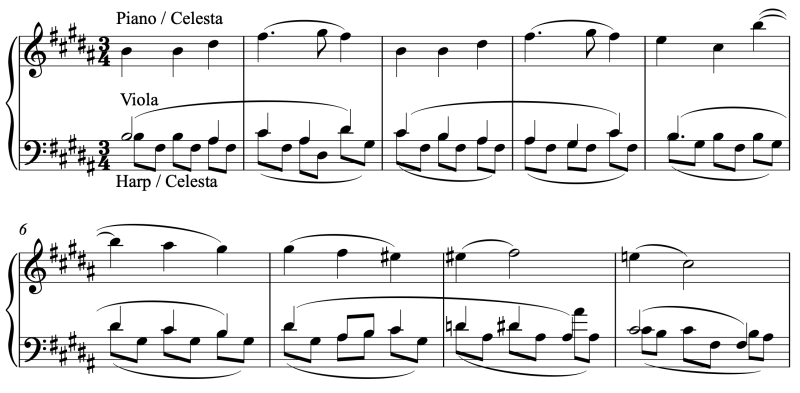

Consider the two sides of childhood depicted in The BFG. In a scene midway through the film (47:11, Clip 13), we can observe the adventures of Sophie (and her giant friend) depicted with a jumpy melody, running 16th notes, and “playful” chromaticism—the “fantastic” dimension. A more reserved portrait of childhood is exemplified in an earlier scene (29:32, Clip 24), in which Sophie begins to trust the strange creature she has just met (Figure 1). Childhood is represented here with a simple, diatonic, major-mode melody in a high register; sparse orchestration; and prominence of piano (colored by celeste)5—the “idyllic” dimension.

Clip 1

The BFG, catching a phizzwizard (47:11).

Crédits: © Walt Disney Pictures

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157693786

Clip 2

The BFG, Sophie begins to trust the BFG (29:32).

Crédits: © Walt Disney Pictures

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157693837

Figure 1

The BFG, first measures of the cue “Building Trust.”

Such idyllic childhood moments stand out in Williams’s body of work for two reasons: the sheer number of times they occur across his oeuvre; and the striking degree to which they are musically and dramatically marked or offset in the film. These moments are fundamental to a common characterization of Spielberg’s output as “elevat[ing] childhood qualities such as naïveté, innocence, and curiosity to a blissful, sublime state, impelling viewers to assume this state, reduced to awestruck children” (Balanzategui and Kristjanson 2016, 183). We can observe them in Williams’s scores for other directors as well. These idyllic representations are sometimes considered evocative of childlike wonder (Richards 2018, 142; Bourne 2024, 93-95),6 but as this paper illustrates, they contain additional layers of emotional and dramatic complexity.

This idyllic childhood mode is not unique to Williams, and many other composers (such as Ravel, Tchaikovsky, or Britten) have more famously represented childhood in their compositions.7 Yet perhaps only Williams has so habitually afforded childhood such a privileged, almost spiritual place. An apparent musical simplicity belies the emotional richness of many of these scenes, and he at times contradicts the topic’s associated expectations. In what follows I will demonstrate the strategies Williams uses to fulfill or disrupt the idyllic childhood topic. In all cases his work serves to idealize the concept of childlike naivety, doing so at critical junctures in his films.8

Contextualizing Williams’s depictions of childhood

Williams is part of a long tradition of composers who have devoted special attention to childlike naivety through their music. Much has been written about the naïve “Romantic child,” a construction of the eighteenth century that glorifies childhood as a distinct realm free from these burdens (Nikolajeva 2013, 321): as Paula Fass explains, writers and artists since this time have depicted childhood as “a privileged ethereal realm that we all desire personally and socially” (2013, 7). Sharp (2000, 67) contends that the first musical composition to represent this idealized condition of childhood was Schumann’s 1838 Kinderszenen. However, this impulse can be traced earlier, and can be aligned more closely with the development of modern ideas of childhood during the eighteenth century as well.9 Nostalgia for childlike innocence in fact existed in a great deal of music in the half-century preceding Kinderszenen, often presenting in the more abstract form of naivety. As Friedrich Schiller asserted in 1795, the “naïve manner of thinking” is only possible in “children and people with a childlike disposition” (Schiller 1795).

While the idealization of childhood naivety is commonplace in modern society, to call someone “naïve” today is generally not a compliment. This was not always the case. Describing a grown artist as naïve was, until the early nineteenth century, high praise (Friedman 2021, 703). Naivety was generally seen as representing closeness to the divine, and with it access to knowledge, true beauty, and an understanding of life’s mysteries. It also was considered an antidote to the excesses of an increasingly modernizing and urbanizing world, and all the anxieties that came with it (Bottge 2006, 250–251). This state of detachment was thus highly desirable. Beyond a small selection of artists, only children were considered blessed with such powers, as the Schiller quote above suggests. Children were accordingly revered, indicated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s famous urging in his 1762 treatise Émile to “hold childhood in reverence” and preserve their cherished, ephemeral innocence (1961, 71). Given the weight afforded naivety at the time, some of the era’s most influential thinkers, including Diderot, Kant, and Schiller, contemplated how this condition achieved representation in the arts (Friedman 2021, 689–693).

Certain musical characteristics were considered representative of naivety. We can observe the musical connection between naivety and childhood by comparing an 1805 description of “naïve” music by C.F. Michaelis with Sharp’s and Bourne’s contemporary definitions of music for childhood (Table 2).

Table 2

|

Michaelis on “naïve” musica |

Sharp on music for childhoodb |

Bourne on music for childhood in filmc |

|

| Melody | “Melody is easily flowing” | “Relatively easy to take in at a first hearing, with few surprises” | “Singable, simple melody” |

| “Affinity with folk music” | |||

| “Melodic writing is significant” | |||

| Rhythm | Avoids “rhythmic illusions” | “Neat and tidy” rhythm and meter | “Singable, simple melody” |

| Harmony | “Harmony is artless, simple, and natural in the chords and phrases” | “Intervals of thirds and sixths are often to the fore” | “Parallel thirds” |

| “Modulation without bold leaps and striking alternations” | “Affinity with folk music” | “Diatonicism, pentatonicism” | |

| Avoids “shocking dissonances” | |||

| Texture | “Their movement is even and mild” | “More emphasis on the vertical (harmony) than the horizontal (counterpoint)” | “Sparse texture” |

| Orchestration | Avoids “striking [orchestral] reinforcements”d | “Timbres and sonorities are fairly bright, but unadventurous” | “High instrumentation” |

| “Sparse texture” | |||

| Development | “Free from strong contrasts” | “Little sense of development apart from variation” | |

| a. Michaelis 1805, 149–150. b. Sharp 2000, 60–61. c. Bourne 2024, 93. d. Ferdinand Hand expanded on Michaelis’s definition in 1837, specifying the importance of avoiding “full-throated instrumentation” (Hand 1837, 302–303). |

|||

Shared characteristics of music depicting childhood and naivety.

Music written to depict childhood from the mid-nineteenth century to the present, as described by Sharp and Bourne, has clear overlaps with the well-established “naïve” music described by Michaelis in 1805. Indeed, a discussion of naïve music in 1837 by Ferdinand Hand essentially reproduces Michaelis’s definition, but describes it as characterizing the “naivety of childishness” [Naivetät der Kindlichkeit] rather than simply naivety (1837, 303). It is apparent, then, that naivety and childhood were conceptually and musically intertwined.

The composer who most closely represented naivety for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century listeners was Joseph Haydn, whose compositions, according to E.T.A. Hoffmann, are dominated by “a feeling of childlike optimism” ([1810] 1989, 97). For Hoffmann, Haydn’s symphonies evoke the following scene:

Youths and girls sweep past dancing the round; laughing children, lying in wait behind trees and rose-bushes, teasingly throw flowers at each other. A world of love, of bliss, of eternal youth, as though before the Fall; no suffering, no pain; only sweet, melancholy longing for the beloved vision floating far off in the red glow of evening, neither approaching nor receding.

Haydn enjoyed towering fame in his lifetime, in part due to his ability to tap into this zeitgeist with his music (Friedman 2021). Although the artistic currency of childlike naivety dwindled over the course of the nineteenth century—Wagner, for example, derided it as sheer vapidity (Wagner [1872] 1966, 264),10 and Dickens believed it to be an irresponsible retreat from reality (Dickens 1853, 337)—this element of nostalgia for simpler times, for the uncomplicated, blissfully ignorant existence of childhood, has remained firmly rooted in Western culture through the twenty-first century (Grant 2013, 120). This is especially palpable in the film music of John Williams, a body of work that has reached billions across the world.

It might be little coincidence that Williams has named Haydn as his favorite composer (Morrison 2020), whom he describes, using language reminiscent of aforecited writings on childlike naivety, as “one of the purest, most instinctive talents in the history of music” (Sullivan 2007).11 Williams continues the tradition of idealizing naïve simplicity in the arts by persistently emphasizing an archetypically Romantic notion of childhood: as a peaceful, safe, spiritual retreat from the darkness of the adult world.

Fulfilling the childhood topic

The following discussion considers several films in which Williams uses the idyllic mode identified earlier to represent childhood as a refuge of security and happiness. It will demonstrate that Williams achieves this aim by deploying either one of two seemingly opposing approaches: conventional fulfillment of the childhood topic, or by subverting its expected tropes. In both approaches, he uses similar salient strategies to offset these moments from the rest of the film.

Common techniques : preparation and contrast

First, it will be useful to specify two strategies that Williams tends to employ to heighten the dramatic effect of these moments: preparation and contrast. The former is a similar concept to his well-known “gradual disclosure of the main theme” (Audissino 2021, 145; Schneller 2014, 101–103), whereby fragments of a theme are presented over the course of a film before coalescing into a complete statement at a climactic moment. Bribitzer-Stull (2015, 101–102) identifies this technique of “presentiment” as a favored one of Wagner, and it is a key factor in what Schneller (2014) terms “teleological genesis,” a particular approach to film scoring that aims for a cohesiveness of musical form and structure alongside that of the film.12 This priming and payoff approach intensifies the drama at the moment of complete disclosure (Bribitzer-Stull 2015), which “comes only at a strategic point in the narrative” (Audissino 2021, 146). Williams most famously executes this in E.T., Jaws, and Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981) (Audissino 2021, 146–147; Schneller 2014, 101–103). According to Williams, these are important moments that, due to musical preparation, are “inevitable” and “had to happen” (Williams, interviewed in Stock 2006).

Williams’s idyllic childhood scenes do not offer the same high drama as the more memorable payoffs of E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the priming is not as extensive, but the tactic is similar. When treating idyllic childhood, Williams may subtly hint at a fragment that is completed in a later scene (The BFG, Empire of the Sun, A.I.), or it might be a fully realized melody that is transformed into an idyllic childhood version via alterations in instrumentation, texture, tempo, etc. (Hook, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone [Chris Columbus, 2001], Jurassic Park, The Reivers [Mark Rydell, 1969]). Considering the extensive commentary on the narrative significance of these instances (Audissino 2021; Bribitzer-Stull 2015; Schneller 2014), and Williams’s (2006) own label of them as “inevitable,” his decision to prime these moments seems to indicate an understanding that these idyllic childhood scenes are critical for the dramatic and emotional arc of the film.

The technique of contrast refers to salient departures in character, texture, tempo, register, harmony, instrumentation, or other musical elements with the deployment of the childhood topic. This technique is less well-defined and discussed in the literature than preparation, but it is palpable in each of the Williams films under examination in this paper. Its dramatic significance derives from a clear impulse, common across these examples, to portray childhood as an entirely separate realm. It is a logical choice when we consider that a key feature of the Romantic child is its inaccessibility. This carefree, naïve time of life can never be returned to or recaptured, fated to be an object of bittersweet memory. Williams employs several techniques to conjure the feeling of departing to a distant world: it might be localized, couching gentle, consonant music within something more dissonant, gloomy, or agitated (Harry Potter, Jurassic Park, Jaws, A.I.); or it might be a broader affective contrast relative to the rest of the film (Jaws, Empire of the Sun, Hook). His habitual use of celeste imparts a shimmering, dreamlike sensation, heightening the impression of the moment as a portal to another world.

Childhood as a separate realm: Hook and Harry Potter

Efforts to make childhood feel special, magical, and inaccessible can be observed in central scenes in Hook and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Both films are clearly centered on the theme of magic, but their scores differ in how they musically isolate childhood.

A broad affective contrast is seen plainly in Hook, Spielberg’s spiritual sequel to Disney’s 1953 animated film Peter Pan (Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske), which envisions a scenario where an adult Peter Pan has forgotten his magical childhood. Discussing the film, Williams describes the world of our imagination as “The one we would like to exist and the one only children have the privilege to dream of or create” (Williams, interviewed in Fourgiotis 1992). Indeed, the film articulates this dichotomy on a broad scale, with the music playing an important role in doing so. Throughout, Spielberg and Williams engage intensively with the fantastic dimension of childhood—as one reviewer writes, “much of the movie seems wired and over-eager when it ought to be refreshing and relaxed” (Sterritt 1991)—but the idyllic dimension reigns in one long, central scene (01:36:49, Clip 3) when Peter Banning recalls his past as Peter Pan, and his decision to walk away from eternal life as a child to become a mortal adult.13

Clip 3

Hook, Peter remembers his childhood (01:36:49).

Crédits: © TriStar Pictures

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1159696350

The music of this scene has been primed by an earlier statement in the film with slow and dreamy high winds to accompany Wendy’s first appearance (10:29). Here it exhibits signals of the idyllic childhood topic: a simple, diatonic, major-mode melody in a high register; sparse orchestration; and prominence of celeste. Furthermore, the regular, rocking nature of the melody and the bass line instills this with a lullaby-like quality, and the use of the Lydian mode heightens the scene’s magical feeling.14 This musically illustrates an uncomplicated naivety that adults ascribe to childhood, with overwhelmingly positive connotations. The marked nature of this music in the context of the film helps privilege this scene among others, representing a critical turning point in the narrative. It is certainly a departure from the jazzy, emotionally flat tune Williams uses to depict Peter as a work-obsessed and emotionally distant father (03:58).15 This inability to access pure childlike naivety is something Williams consistently represents in his music, often by sharply contrasting depictions of idyllic childhood with surrounding musical material.

The score to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone offers another striking example of how Williams isolates childhood naivety. He uses the twinkling of celeste often in the film to connote “benevolent magic” (Webster 2009, 205), which makes it difficult to manufacture a departure to the childhood realm, given how heavily he relies on the instrument to depict idyllic childhood. Moreover, the film’s opening contains a brief but conspicuous instance of the childhood topic via the celeste, which introduces the film’s main theme—titled “Hedwig’s Theme”—when we see baby Harry’s face for the first time (03:44). However, there is a more consequential moment in the film’s exploration of childhood innocence. This occurs when Harry gazes into the magical Mirror of Erised, which shows the deepest desire of those who peer into it.

When Harry looks into the mirror midway through the film and sees his deceased parents, Williams seeks to highlight the happy childhood Harry longs for, turning to unconventional instrumentation to set this scene apart (01:33:16, Clip 4).16 Williams uses woodwinds to prime this melody in an earlier scene where Harry wishes himself a happy birthday, before Hagrid arrives to take him to Hogwarts (12:38 and 18:18). In the later mirror scene, it features typical tropes of the idyllic childhood topic—major mode, a singable melody (albeit with some chromatic detours), sparse texture, and high register instrumentation—with the added presence of an unusual tinkling sound, made by crotales. They serve a dual function here: they fulfill the childhood topic as a high, bell-like percussion instrument, and their antique sound, lacking exact pitch and being associated with medieval music, enriches the mystical feeling of the scene. Combined with a sudden harmonic shift from dark, modal D natural minor to a lusher A-major sound world, the use of the crotales transports viewers to a different plane from the rest of the film; just like Harry is momentarily transported to a childhood in which he knows his parents. This sense of contrast is heightened by the busy strings that immediately follow, as if rousing Harry from a dream.

Clip 4

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry gazes into the Mirror of Erised (01:33:16).

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1MvLNZFaWko

Other interpretations of this music do not consider it a reflection on Harry’s lost childhood. Webster suggests that the melody captures Harry’s “love for his family” and the “childlike nature” of his emotions (2009, 372–373); Obluda asserts that, rather than merely “simplicity and sincerity,” this scene “reinforce[s] the otherworldliness that looms over Harry as he tries to make sense of his fame and destiny in a world he had previously been unaware of” (2021, 57).17 Both writers acknowledge Harry’s innocence, but their commentary neglects the notion that by using childhood tropes and creating such a sharp contrast with the surrounding musical material, Williams also seems to represent the precious nature of childhood itself. This interpretation becomes more convincing when comparing it to a similar musical moment in The Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus, 2002), during a quiet, intimate scene when Harry and Ron visit a petrified Hermione in the infirmary (01:51:18). The same melody is heard,18 but it is now voiced by an oboe (an instrument associated with Hermione in the film), without the orchestrational trappings of the idyllic childhood topic. This is a departure from the parallel scene in the first film, which narratively and musically stands apart as a specific expression of the transience of Harry’s childhood innocence, rather than the more generic “love for his family and friends” that is centered in the corresponding moment of The Chamber of Secrets.

Williams does not return to the idyllic childhood topic after the Mirror of Erised scene in the three films he scored for the franchise. In this he participates in a palpable evolution over the course of the saga, which has been described as traversing “innocence” to “experience,” beginning most notably with The Prisoner of Azkaban (Alfonso Cuarón, 2004), the third and final film scored by Williams (Webster 2009, 401–402; Behr 2009; White 2018). The young protagonists’ connection to childlike naivety erodes as innumerable horrors strip them of the ephemeral innocence that the first two films (directed by Chris Columbus) especially highlight. White observes this evolution represented musically in the post-Williams films (scored by Patrick Doyle, Nicholas Hooper, and Alexandre Desplat) in several ways: for example, striking silence during moments of intense grief “serve to counteract the more childish sense of wonder at the magical world” displayed most prominently in the “Innocence” films scored by Williams (2018, 134); chromaticism representing “evil” rather than “magic,” as it does in the earlier films (2018, 134); and diatonicism, most notably through the progressive alteration of Hedwig’s theme, that moves the films further from the “benevolent magic” world of the Williams films (2018, 74–81).19 The absence of idyllic childhood scenes in films 2–8—perhaps inevitable as the characters grow older—is another factor in this disconnection from naivety. As for Williams, the score for The Prisoner of Azkaban goes beyond merely avoiding the idyllic childhood topic, using techniques such as emphasis on strings to channel “a growing awareness of loss in Harry’s emotional world” (Webster 2009, 401–402).

Childhood and safety: Empire of the Sun and Jurassic Park

In creating a sharp distinction between childhood and adulthood, Williams makes a statement that these are fundamentally different elements of the human condition. Fulfilling the idyllic childhood topic to create a distinct aural experience offers a natural way for Williams to convey the message that childhood is a safe place in a dangerous world. Consider the straightforward musical representation of childhood in Empire of the Sun, which follows a young boy named Jim in a Japanese internment camp in China during the second World War. His youthful innocence and enthusiasm represent a ray of hope in miserable, oppressive conditions, and distinguish him from the others from the moment he arrives at the POW camp (01:06:53, Clip 5).20

Clip 5

Empire of the Sun, Jim arrives at the POW camp (01:06:53).

Crédits: © Warner Bros.

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157693965

Upon his arrival Jim walks through the sea of toiling laborers, transfixed by an airplane, almost oblivious to the suffering around him. Amidst this cacophony, a celeste intones a melody heard earlier in the film: when Jim’s parents wish him goodnight in the comfort of his own home (08:36).21 Again we can observe an aurally offset deployment of the childhood topic: both by the diegetic cacophony, as well as the fact that the score has been silent for nearly a half hour at this point. This brief phrase contains several tropes associated with the childhood topic: high instrumentation (celeste), sparse texture, and a singable, diatonic, major-mode melody. The music quickly shifts from the childhood topic to something more lush and romantic, but by recalling a time of peace and security with his parents, the message of the music is clear: Jim’s childlike naivety might allow him to cope with the harshness of his environment in a way that sets him apart from his elder peers. It also enables him to transcend the language barrier and the power imbalance between him and his captors, resulting in what Frank Lehman terms a cinematic “holy moment” (2018, 200). Childlike naivety thus serves as a common denominator, appearing powerful enough to bring peace in war. Yet the film explores the fragility of this power: Spielberg relates that Empire of the Sun is about “a very cruel death of innocence” (Johnston 1988, 13, quoted in Sinyard 2017, 240). This scene of pure idyllic childhood therefore serves a key emotional and dramatic role by sharpening the loss of Jim’s naivety, and placing it in clear relief against the horrors he experiences.

Childlike naivety as an oasis of peace amidst violence and trauma is an important theme of Jurassic Park, which contains one of Williams’s most well-known musical depictions of childhood. Yet rather than the focus being on the preservation of a child’s inherent innocence, as observed in Harry Potter and Empire of the Sun, Spielberg and Williams here consider an adult’s epiphanic reconnection to childhood, akin to the approach taken in Hook. In this scene (01:23:25, Clip 6),22 the paleontologist Alan Grant, along with the two grandchildren of the park’s owner (John Hammond), have climbed up a tree for safety from a vicious T-Rex. Dr. Grant, who has previously shown disdain for children, now joins them in marveling at the magical dinosaur sounds coming from the forest, and promises to keep watch as they sleep. The typical markers of childhood are exhibited here: a singable, diatonic, major-mode melody, played in a high register by a celeste, and sparse orchestration. We might also note the prominence of the dotted rhythm, giving the cue a strong sense of rocking, reminiscent of a lullaby. Similarly to the “Remembering Childhood” scene in Hook, the overall impression is that of a music box, which has associations with childhood and infancy.

Clip 6

Jurassic Park, Alan and the children rest in a tree (01:23:25).

Crédits: © Universal Pictures

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157694010

What effect does Williams’s straightforward musical depiction of childhood have on the film’s narrative? A key driver of Jurassic Park is Dr. Grant’s evolution from a humorless scientist who detests children to a more caring, responsible “family man.” Just like Peter Banning’s reawakening to his own childhood as Peter Pan allows him to become a better father, Grant’s recovery of childlike wonder enables his transformation—this is something the music makes clear.

We can observe this by comparing the presentation of the melody in the tree scene with the first time we hear it in the film, which appears in the track “Welcome to Jurassic Park” (20:21). In this earlier scene, Williams channels Grant’s awe at the miracle of Jurassic Park with a noble, brass hymn that eventually becomes celebratory, marking a triumph of science over nature. Paralleling this are Grant’s breathless scientific observations, indicating that much of his awe may be derived from his paleontology background. Conversely, in the “Tree for My Bed” scene, Williams’s redirection of this melody into the intimate, idyllic childhood topic reflects how Grant, who previously disliked children, now regards these dinosaurs with something closer to childlike wonder, in turn enabling him to connect with, and protect, Hammond’s grandchildren. The message that Williams conveys with the childhood topic—which feels like an oasis amidst more intense, agitated music—is that childlike innocence is a place to retreat to for peace and safety in a scary adult world, a retreat that must be protected.

Indeed, the celeste figures prominently in the subsequent scene as Hammond explains how the imagination of his youth inspired the well-intentioned spectacle of Jurassic Park (01:26:00); yet the childhood topic now yields to something more haunting, perhaps casting the park as an adult perversion of those days of childlike wonder. The celeste gently returns in the closing moments of the film (01:58:55) as the group of survivors flees the island in a helicopter, the children sleeping on Grant’s shoulders. Ending the film by visually and aurally recalling the “Tree for My Bed” scene—with the “Welcome to Jurassic Park” melody returning once more—lends prominence to its message about childhood.

Disrupting the childhood topic

Childhood as a “precious refuge”: Jaws and A.I.

As we have observed, when Williams seeks to portray childlike naivety, he habitually calls on the piano, celeste, and/or harp for a simple, sparsely-orchestrated, singable, major-mode melody. However, there are also instances of Williams disrupting the typical presentation of the childhood topic in a way that adds emotional and narrative nuance and enriches lofty portrayals of childlike naivety. Two moments that exemplify this can be found in Jaws and A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

Williams treats one striking wordless scene in Jaws with characteristic musical sensitivity. In this scene, Police Chief Martin Brody, grappling with a great white shark terrorizing his small town, shares a touching moment with his toddler-age son, Sean (38:05, Clip 7).23 Here, what we have identified as the idyllic childhood topic manifests in the score’s simple, high-register, major-mode melody, played by piano, harp, and vibraphone. But it departs from the topic in two ways: the dissonant pedal played by celli and basses that undergirds the scene, and the halting nature of the melody. These disruptions highlight the archetypal relationship of Romantic child and father, in which the Romantic child is, in Matthew Riley’s words, “an icon of a domestic realm that offered the husband a precious refuge from the cut and thrust of the competitive world of work” (2007, 119).24

Clip 7

Jaws, Martin shares a touching moment with his son (38:05).

Crédits: © Zanuck/Brown Productions / Universal Pictures / Cinema International Corporation

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157694043

The bass pedal is an open-string C (the lowest and darkest playable note on celli and basses) against an entirely diatonic D-major melody. The associations forged in Jaws between low strings and the lurking danger of the shark, combined with this striking dissonance, serves to underpin Brody bringing the melancholy and darkness of the outside world into his home, to be met by the “precious refuge” of his son Sean’s playful unknowingness. Williams makes audible the unattainability of Sean’s naivety, as the piano-harp-vibes melody seems to exist in an entirely separate world—in mode and character—from the music that preceded it, and indeed is spatially distant from the low-register bass pedal that represents danger. Similarly, Sean is insulated from the burdens faced by his father—he mimics his gestures, but does not understand the torment of the adults around him.

Unique about this melody among most other iterations of the childhood topic is that it is not particularly singable. Its halting, irregular nature evokes a minuet-like atmosphere, as if Williams were depicting a dance between father and son. They are on a more equal playing field than in the dynamic of the singable lullaby, in which a parent comforts a child; here, the child comforts the parent. This bond offers a measure of peace for Brody as he momentarily adopts his son’s naïve worldview. This is a pivotal moment in the film, as well as its emotional center: fresh from being reproached by a mourning mother, Brody looks to Sean’s naivety for peace and direction, and leaves this interaction with increased resolve to ensure the shark is killed and to preserve the imperiled naivety that defines the island.

The “precious refuge” of childhood is treated with more complexity in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, which features as its protagonist David, a robot engineered to be the ultimate naïve child. This android character maintains his wide-eyed, exaggerated naivety throughout the film, even as he is abandoned by his mother, survives a robot holocaust, and undertakes an epic journey in a desperate attempt to “become a real boy” so that his mother, Monica, will love him like a human child. Williams reserves his most conspicuous engagement with the idyllic childhood topic for the very end of the film, when David awakens after a 2000-year slumber to find himself back home (02:01:36, Clip 8).25

Clip 8

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, David awakens to find himself back home (02:01:36).

Crédits: © Warner Bros. / DreamWorks Pictures

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1157694065

Williams employs his familiar techniques of preparation and contrast to achieve a remarkable payoff at this juncture. We hear a hint of this melody earlier in the film when Monica “imprints” on David to activate his functionality as her son (23:54), with celeste connoting the magical and supernatural. The later deployment of “Monica’s Theme” is furthermore a striking aural contrast to the disorienting, dissonant music heard immediately beforehand, as David opens his eyes and seeks to make sense of his surroundings. This musical fulfillment contributes to a powerful catharsis in the film’s closing moments.

The complex emotions of this scene—joy, wonder, confusion, nostalgia, and trepidation—are represented by a simple, song-like, major-mode, diatonic melody, played alone in a high register by a solo piano. The simplicity and songfulness of Williams’s cue evoke a lullaby, just like other instances of the childhood topic we have examined in his scores for Hook and Jurassic Park. However, several departures from more typical instances of the childhood topic color this scene with remarkable emotional complexity. These departures in orchestration and melodic treatment eschew the “music box” presentation of the childhood topic that we observed in each of the examples explored in this paper, conferring it with an unusual layer of gravitas and amplifying the impression of this scene as a dream or a memory.

To begin, the melody is laden with reverb, which heightens the scene’s nostalgic quality: unfocused memories of childhood can feel like they are never as sharp as we might like, eternally elusive, forever slipping through our fingers.26 Yet sometimes we can be gripped by a truly powerful memory—to live in that memory, to experience it as almost real, is to be momentarily suspended in time. Williams captures this sense of timelessness with an undulating accompaniment, which seems to have neither beginning nor end, no clear melodic or rhythmic profile, like an endlessly flowing stream—contrasting the more clearly-metered accompanimental figures of the music box.27

The melody itself also embodies this sense of flowing, and seems to avoid a clear direction, which broadly contributes to a dreamlike state. Swanson (2018, 382–384) has illustrated that for all its seeming straightforwardness, the melody does have a number of unexpected twists and turns, never quite settling where we might expect. Williams himself has acknowledged the “complexities” of Monica’s theme, which he identifies as a cantilena (Swanson 2018, 381).28

In complicating the regularity of the childhood topic, these subtleties also endow the theme with more emotional nuance (Figure 2).

Figure 2

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, “Monica’s Theme.” Transcription from Swanson (2018, 383).

For example, a rising stepwise figure reaches the leading tone but does not resolve upward—this suggests a sense of yearning and unfulfilled desire (Swanson 2018, 383), which is augmented by the deceptive cadence on the following downbeat. Soon afterwards, a pre-dominant progression unexpectedly cuts to the tonic, similarly thwarting an anticipated resolution, but rhyming with the numerous falling figures that straddle most of the theme’s measures. Bottge draws attention to a similar eliding of the dominant-tonic progression in Brahms’s Wiegenlied, which she reads as a metaphor: it creates a place of timeless safety, obscuring the separation of “underdeveloped” child (dominant) and “maternal, grounding” mother (tonic) (2005, 206). The small descending leaps here can be heard as sighs—traditionally musical signifiers of melancholy (Taruskin 2013, 291). Such falling figures deflate tension, creating moments of repose that connote David’s achievement of inner peace. We might be reminded here of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s description of Haydn’s naïve music: “A world of love, of bliss, of eternal youth, as though before the Fall; no suffering, no pain; only sweet, melancholy longing for the beloved vision floating far off in the red glow of evening, neither approaching nor receding” (Hoffmann 1989, 97).

All of these qualities infuse the theme with lyricism and elegance that are unique among the examples considered in this paper thus far.29 The fact that Williams uses only solo piano is in itself a departure, as each of the other scenes relies on some combination of piano, harp, vibraphone, and celeste: a combination that creates a tinkling timbre reminiscent of the childhood topic’s customary music box presentation. We can furthermore contrast Monica’s Theme with the more mechanical and static iterations of the idyllic childhood topic observed in the earlier examples. When Williams fully orchestrates the melody in an ensuing scene showing David reuniting with his mother,30 it seems to reveal a kinship with Mozart’s piano concerto slow movements, with its long melody, expressive songfulness, and prominence of soloistic winds in a chamber orchestration.

Williams’s deployment of an English horn countermelody in that context offers an immediate cue to this linkage, as Mozart often relied on solo winds in piano concerto slow movements (Rogerson 2019).31 The connections deepen upon further examination of the theme itself. Scott Burnham (2013, 3–36) has discussed at length Mozart’s proclivity for oscillating accompaniments, particularly in concertante movements (for example, the slow movement of the Piano Concerto in C Major, K. 467 offers some textural and characteristic resemblance to this setting of Monica’s Theme). In such passages, “the rhythmic relation between pulsating accompaniment and slower moving melody creates an animated stillness” (Burnham 2013, 10). More specifically, in the Adagio of the Clarinet Concerto, K. 622, which like Monica’s Theme is supported by an undulating figure, Burnham observes a passage that “hums with the exquisite tension of keeping things in suspension” (2013, 10). This imagery of “animated stillness” and “suspension” elicits a clear connection to Monica’s Theme, which was described above as keeping us “suspended in time.” Burnham also helps us draw a connection between the two passages by noting how subtle swerves in harmony and melody yield “the effect of a floating, suspended tonic” (2013, 10). Finally, we can also observe that several of Mozart’s best-known soloistic movements open with a measure or two for the accompaniment to be heard on its own before the melody’s entrance, as Williams does in Monica’s Theme.32

Taken together, these elements suggest a possible allusion to, or inspiration by—consciously or not—the most famous child wunderkind in Western culture. There may be significance in this, as Mozart was someone whose true naivety, it was held, enabled human artistry to reach a divine peak (Wagner 1850, 40). David’s enduring naivety also grants humanity another kind of timeless legacy at the end of the film. In opting against a music-box presentation in favor of Mozartian elegance, Williams contributes solemnity and grace to the eternal longing of a child for his mother, to a robot’s poignant, innermost wish to become a human, simply so he can experience the sweet joys of childhood.33 That Williams treats this theme with such weight seems to suggest that this deep desire to return to childhood is not a trifling wish, but a fundamental feature of the human condition that bonds us all.

How unique are these depictions of childhood?

How does Williams’s approach to childhood differ from other composers? On a very basic level, the existence of a “childhood topic” implies that many others have used similar musical techniques to depict idyllic childhood. Williams is therefore not alone in using major modes, high-register instrumentation, sparse texture, and singable, simple melodies to foreground childlike wonder and innocence. Williams does separate himself from other composers in several ways: his customary use of preparation and contrast, the dramatic significance of these moments in many of his films, and the frequency with which he engages with this topic throughout his oeuvre.34 To contextualize Williams’s approach, we will consider several examples of other composers engaging with the childhood topic, before taking up Spielberg’s role in Williams’s frequent interactions with this theme.

While Williams often takes special care to prepare and contrast his depictions of idyllic childhood, for many composers the childhood topic alone suffices for the purpose of emphasizing the childlike on screen. In an early scene in Jack (Francis Ford Coppola, 1996, 14:45),35 composer Michael Kamen features the idyllic childhood topic prominently as Jack’s tutor argues that, despite an aging disorder causing 10-year-old Jack to appear 40 years old, he is still a child deserving of a true childhood. With a simple, lullaby-like solo piano line, the music serves quite plainly to highlight that Jack, though middle-aged in appearance, is truly a child—an essential function considering the film’s fanciful premise. However, this scene is sandwiched by music that is already playful and childlike in spirit, and it comes at an early, dramatically unmarked point in the film. This is not to suggest that an early appearance of the childhood topic is necessarily without consequence: the aforementioned idyllic childhood moment in The BFG appears early and is critical to the narrative and emotional core of the film, as it marks the building of trust between Sophie and the giant. Also unlike The BFG, the idyllic topic in Jack is not primed or sharply contrasted with the surrounding sonic landscape. Lacking preparation and contrast, and dramatic weight, it therefore does not possess the same emotional and dramatic effect that we observe in other examples in Williams’s oeuvre, notwithstanding its very clear, positive message about childlike naivety.

One characteristic of Williams’s forays into idyllic childhood is that he rarely presents it more than once in a film, using this scarcity to craft dramatically unique and significant moments.36 While this approach is not unusual, there are numerous counterexamples from other composers: The Secret Garden (Agnieszka Holland, 1993), with a score by Zbigniew Preisner, contains six distinct instances of the idyllic childhood topic in just the second half of the film37; Peter Martin’s score for Hope and Glory (John Boorman, 1987)38 and Thomas Newman’s scores to Finding Nemo (Andrew Stanton and Lee Unkrich, 2003)39 and A Series of Unfortunate Events (Brad Silberling, 2004)40 include mirror versions of an idyllic childhood theme near the beginning and ending of their respective films. A Series of Unfortunate Events is a particularly relevant example due to its explicit thematic engagement with the “precious refuge” of childlike naivety. Chronicling the misadventures of three newly-orphaned siblings who must contend with malicious and incompetent adults as they seek a place to call home, the film offers stark contrasts between the innocence of children and the cynicism of the adult world. Newman musically highlights this thematic contrast with the idyllic childhood topic twice during the film, with the same music both times (21:28 and 01:32:17).41 A gentle, sparsely-orchestrated piano line characteristic of Newman underscores these scenes (Audissino 2017, 222). Narratively, recycling the music makes sense: both scenes reference a trip by the late parents to Europe, and the children’s related sense of abandonment.42 Although there is thematic and emotional meaning in these moments, Newman does not engage in the kind of subtle preparation or contrast that we have seen in Williams’s work. There is, of course, a form of preparation in the verbatim reuse of music. This contributes a special poignancy because there is a dual return: a musical return complements the physical, as the children revisit their destroyed childhood home.

It may also be worth acknowledging that the possibility for a sense of departure is also diminished by Newman’s trademark style: whereas Williams is something of a “musical chameleon” (Audissino 2017, 225), Newman features a brand of “non-symphonic minimalism,” which blends “acoustic instruments, light, high-pitched percussion, and electronics in a sparse and terse orchestral texture” (Audissino 2017, 222). The similarities between Newman’s style and the childhood topic are apparent in this description, and may be expressively limiting in terms of drawing contrasts between the childhood topic and the surrounding music or the film’s aural landscape. On the other hand, Williams’s stylistic diversity even within a film can add additional layers of contrast.

Williams is not, however, the only composer to use techniques of preparation and contrast to offset an idyllic childhood moment. Danny Elfman’s score to Edward Scissorhands (Tim Burton, 1990) offers a useful point of comparison as another non-Williams project that uses familiar musical techniques and clearly subscribes to a Romantic notion of childhood: as Walling observes, director Tim Burton “hopes to show that it is not the naïve, natural artist who needs to grow up; rather, the fault lies with a society that has matured into a world that is intolerant and vicious because it gave up the broader consciousness of trust, honesty, and make-believe exhibited by Edward” (2014, 76–77). Yet we can still note subtle differences in the musical handling of childlike naivety between Elfman’s score and the examples examined thus far by Williams.

There are a number of Williams-esque techniques in Elfman’s treatment of the childhood topic in Edward Scissorhands: a timeless idyllic childhood moment at the midpoint of the film (53:17, Clip 9)43 features celeste, contrasts conspicuously with the preceding music (a bombastic passage evocative of Aram Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance,” and later a pompous tango),44 and is prepared by subtle motivic hints during a child’s bedtime story at the outset of the film (02:53).45 But beyond this sharp aural payoff, the narrative message is a bit muddled: the childhood topic (and this very theme) permeates the score, with celeste featured in many scenes. This scene could therefore reference the fact that Edward is a childlike character, experiencing a moment of childlike wonder as he sees Kim out with her friends; the music also hints at the identity of the elderly bedtime storyteller from the film’s opening (Kim), and could be considered Kim’s theme, or a love theme; it is also heard later (01:25:00) when Edward has a flashback to being presented with prosthetic hands by his “inventor,” and again moments thereafter when The Inventor collapses (01:26:20).46 With these myriad associations, one reviewer identifies two functions: as both a love theme, and a “Story-Telling Theme” (Lysy 2019). While the central scene that features this theme does serve to highlight a contrast between a “vicious” world and “trust, honesty, and make-believe,” these are not coded as the binary of “child” and “adult” in the same way that we observe so clearly in Williams’s scores.

Clip 9

Edward Scissorhands, Edward’s childlike moment of wonder, underscored by celesta (53:17).

Crédits: © Twentieth Century Fox / Walt Disney Studios

Permalien: https://vimeo.com/1159703903

We might wonder how much of the subtle differences between Williams and other composers is the result of varying compositional approaches, instead of reflecting a director’s vision. This is especially relevant when we consider that the incidence of childhood themes in Spielberg films is objectively higher than in the average director’s body of work (Schober and Olson 2016), and Williams has scored nearly all of Spielberg’s films.47 It is worthwhile, then, to consider how Spielberg fits into this discussion of Williams’s glorification of childlike naivety.

Numerous commentators have argued that Spielberg does not offer particularly rosy portrayals of childhood. As Schober observes, while Spielberg has a reputation for envisioning childhood as “all sweetness and light,” there are nonetheless “darker underpinnings, increasingly fraught with tensions, conflicts, and anxieties” in Spielberg’s children (2016, 1). Lester Friedman also contends that Spielberg’s “portraits of children rarely dissolve into maudlin paeans to some idyllic existence” (2006, 32) thereby contradicting assumptions that Spielberg solely concerns himself with Romantic ideals of childhood. Yet as we have seen, a “paean to some idyllic existence” is exactly how Williams’s music treats childhood in the particular scenes at the heart of this paper’s investigation, reflecting Romantic ideals of childhood and naivety.

Consider A.I. as an example. Spielberg’s treatment of childlike naivety in A.I. is rather ambivalent—in this film, childhood can at times feel less like a “precious refuge” than a lens through which to see the ills of the modern world. Indeed, David’s mother is forced to abandon him when his everlasting naivety proves potentially harmful to their real biological child. Yet notwithstanding a considerable number of dark, haunting moments in his score that reflect this threat, Williams leaves viewers with music that elevates and refines the child’s extreme naivety, complementing or suppressing, rather than expressing, the film’s nihilistic themes. This is not to suggest that his approach is some kind of dissent with Spielberg’s vision, who indeed sought to craft a “bleak film about human nature disguised as a sentimental science-fiction fairytale” (Tobias 2021). As A.O. Scott (2001) writes in his review of the film, “The very end somehow fuses the cathartic comfort of infantile wish fulfillment—the dream that the first perfect love whose loss we experience as the fall from Eden might be restored—with a feeling almost too terrible to acknowledge or to name.” Williams’s music plays a prominent role in supplying the naïve fairytale of “infantile wish fulfillment,” contrasting mightily with the “darker underpinnings” that permeate Spielberg’s film.

The score to Empire of the Sun has been understood as exhibiting a similar duality (Schober 2016, 9; Hinson 1987). Schober (2016, 9) describes it as “two films joined at the hip”: one, representing Spielberg’s “Romanticism, with its emotional uplift apropos a boy’s obsession with the wonders of flight and gung-ho of war,” is “underscored by John Williams’s score”; the other “chronicles the brutalities of life in a Japanese internment camp.”48 Schober does not describe the relationship between Williams’s score to the second “film,” but multiple reviews of Empire of the Sun and its soundtrack have used terms such as “ghostly” (Broxton 2018; ClassicFM s.d.) and “haunting” (Broxton 2018; Barsanti 2020). It is therefore reductive to describe Williams’s role in Empire of the Sun or A.I. as merely the film’s conduit or representative of childlike naivety, but the fact that Schober only discusses Williams in this one “Romantic” sense indicates a particular vein of reception: that Williams’s music, in these films and others, often serves to channel the naïve aspects of Spielberg’s films.

This discussion of Empire of the Sun and A.I. indicates the complex role Williams’s portrayals of idyllic childhood can play within Spielberg’s emotionally layered films, suggesting that these portrayals may not map on exactly to the films’ overall message about childhood. A composer, however, cannot manufacture an ideal moment in a plot or narrative for idyllic childhood; they are only truly in control of the music with which they treat such moments. The fact that Williams uses the techniques of preparation and contrast for idyllic childhood in his scores for other directors (such as Mark Rydell, George Miller, and Chris Columbus) suggests that independent of Spielberg, Williams views these junctures as dramatically and thematically critical.49 The frequency of this topic’s appearance in Williams’s oeuvre is likely a result of his collaborations with Spielberg, but Williams has nonetheless forged a distinctive path in representing these moments.

Conclusion

For many composers, the function of the childhood topic is often to emphasize a child onscreen, or a memory of childhood. One senses that there is more at stake for Williams, as his fleeting forays into childhood consistently elevate the dramatic significance of these moments. The plot of Hook hinges on Peter finally remembering his past; the heartbreaking sadness that drives Harry Potter is revealed in the Mirror of Erised; David’s 2000-year journey home movingly culminates in profound wish fulfillment. Ultimately, childhood is often represented as another realm entirely in Williams’s oeuvre, idealized in the way it was in the eighteenth century.

Future research stemming from this paper might explore in more detail how musical approaches to childhood differ by director, or the role gender and race play in representations of childhood. Exploring further how other composers treat childhood would provide more context for this investigation.

It is not my contention that Williams’s depictions of childhood are conspicuously different from those of other composers, despite his occasional subversion of its expected tropes. As mentioned, the fact that we can speak of a childhood “topic” requires many to return to the same well countless times. What is remarkable about Williams’s intimate portrayals of childhood is how often they appear in his work; how we can regularly count on Williams to uphold childlike naivety as a timeless, glimmering refuge from the gloom and grind of existing in the world; and how indispensable these brief departures are to the drama and artistry of each film in which they appear. His oft-acknowledged abilities as a melodist and orchestrator, combined with an impeccable sense of pacing, instill striking poignancy into these moments in a way that sets him apart as a valuable case study for exploring depictions of childhood in film. It is intriguing to consider that, compared with those composers who memorably depicted childhood in their music before him, it is likely none match the frequency and reach of Williams. Over his long career he has crafted a musical representation of our deeply human, collective yearning for this lost Eden.