Introduction

The Tempest is “the most puppeted” Shakespearean play worldwide, thus, as a choice for the Hungarian adult puppet stage it should not be really surprising. Although somewhat reluctantly, we must acknowledge that there is no such thing as adult puppet theatre scene in Hungary, only some productions, few and far between. The subject of this paper, The Tempest directed by Rémusz Szikszai in 20181 is advertised as a 16+ production. Perhaps it marks the first steps in the gradual consolidation of the puppet medium for adult audiences in Hungary but perhaps it is nothing more than the one swallow that does not make a summer. Some, like journalist and puppet theatre producer Tímea Papp, are quite pessimistic about this process,2 that is why it is more than simply notable that most critics3 hailed the production as one which effectively proves that the puppet medium is, in fact, suitable for mature audiences.

Although this paper does not aim to describe the state of twentieth-century Hungarian puppeteering, nor does it mean to deal with the Hungarian stage history of The Tempest, one production ought to be mentioned here, as the earliest of swallows: this (in fact, the only previous puppet) Tempest was staged in 1988.4 At what was then called the State Puppet Theatre, Prospero appeared as the single live‑actor (Dezső Garas) while all other characters were played by puppets: his omnipotent authority figure dominated the scene and dwarfed the rest of the cast. In contrast, Szikszai’s production features a wide variety of characters on the stage, all perfectly visible, including live‑actors, bunraku (child‑size) puppets, plaster heads made after actors’ heads, and prostheses, that is, attachable body puppets which puppeteers can wear.

What is always at stake with puppet performances is whether the puppets add yet another layer to the interpretation or merely decorate it. Garas’ production by casting a live-actor as Shakespeare’s magician quite naturally referred in 1988 to an unequal power situation. But then, what purpose does Szikszai’s variety of puppets serve? In this paper the relations between the bodies of the actors and the bodies of the puppets will take centre stage—besides other devices—so as to point out the place of Rémusz Szikszai’s uniquely mixed, puppet and live‑actor production on the map of twenty‑first century Hungarian Shakespeares.

“Sir, I am vexed” (The Tempest, 4.1.174–175)5

It is not the evident “puppetability” of The Tempest that interested Rémusz Szikszai. In several interviews, for instance, one by Panka Dióssy, the director referred to other, intensely personal reasons for his selection of the play and expressed his profound inner need to consider the issues Shakespeare addressed in The Tempest; most importantly those of achievement and forgiving.6 What is clear from the interviews he gave after the success of the première, is that passing fifty, that is, in Dante’s words, “midway upon the journey of […] life” Szikszai was/is apparently “vexed” and keeps pondering, even in the Epilogue, what strength “I have’s mine own” (2) and whether all “my vexations were but my trials of thy love” (4.1.6). Not surprisingly, what is clear from the production is that, at the conclusion of the tale, Szikszai’s Prospero lies down, apparently not to sleep but to die.

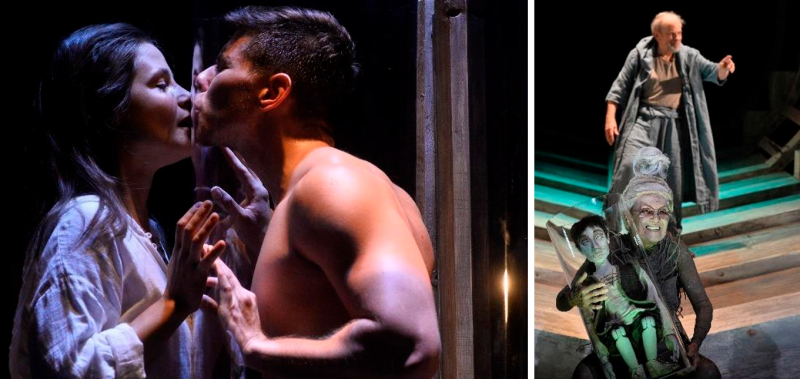

Figure 1. – Tamás Fodor as Prospero in the Epilogue in Shakespeare’s Tempest.7

© Vera Éder.

What Szikszai might have had in mind for the backbone of the production is staging what Christians call a good or happy death, mors bona. It means quitting “this world in the peace of a good conscience” (Prayer for a happy death #7) which is in sharp contrast to the unexpected, “sudden and unprovided death”. People can die, as Stoppard’s omniscient Player once explains in his Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, “heroically, comically, ironically, slowly, suddenly, disgustingly, charmingly, or from a great height” (83), but dying convincingly on the stage, or, ending one’s life with a happy death, is in fact the ultimate life achievement.

Death is an event of certain honourable theatricality, both on stage and off: “It’s what the actors do best”, it “brings out the poetry in them” the Player summarizes. Performers, either on stage or off, “have to exploit whatever talent is given to them” (Stoppard 83). Szikszai makes us face the question, how will we perform it … Tamás Fodor, Szikszai’s 76‑year‑old Prospero, embodies the highly professional player who is able to act out dying convincingly: in the Epilogue Shakespeare gave him time and focus on the page, Szikszai gave him the same on the stage. What precedes his last lines can be seen as an aging person’s preparation for a good death, arranging the chattels and the relationships, providing for the child and “pardoning the deceiver” (The Tempest, Epilogue, 7).

But if Szikszai meant to target an adult audience with the subject of leaving the worldly stage, then why did he choose the puppet medium to convey his message in a culture where puppetry in people’s minds still equals with the somewhat low and silly entertainment for little children? If Szikszai has been working in the live‑actor segment of the Hungarian theatre scene, why did he opt for a variety of puppets, marionettes, prostheses, masks, performing objects, rod puppets and bunraku? How will these colourful toys authenticate his Shakespearean story about Prospero’s death? How will these simple creatures reveal the secrets of a great magician’s ultimate staging?

“You demi-puppets” (The Tempest, 5.1.45–46)

The present Hungarian theatre scene is characterized by the often sadly tangible division between the puppet and the live-actor fields (noted by puppet theatre manager and director Géza Kovács in his opening speech for this year’s World Puppetry Day), and the painful lack of both adult puppet productions and their critical discourse, as puppet director Ágnes Kuthy complained.8 Just a few hundred kilometres and few hours away from Budapest, the cultural position of puppets is quite different: in the Czech lands an unbroken tradition of puppetry is thriving. Puppets have been present in adult performances both in high and popular culture as well as in the academia. For instance, it is puppets, expensive and sumptuously dressed marionettes, that vivify the sombre greys of Prague’s medieval Charles Bridge, and also puppets, in fact the practice and the theory of puppetry, that occupy a great proportion of the issues in Brno’s international scholarly journal, Theatralia / Yorick. In short, puppeteering is seen as an equal amongst the other branches of the performing arts.

Geographically very close to the Bohemian-Moravian context, but practically and intellectually perfectly outside of it, Hungary’s puppet traditions have always been scarce and weak: following two marionette operas written by Haydn at Esterháza / Fertőd to greet Empress Maria Theresa, only the 1930s featured inventive efforts in puppeteering. Regrettably, to make a lasting impression these efforts were either too far away, e.g. Théâtre Arc-en-Ciel in Paris (1929–1940),9 or too short‑lived, or both. The only puppet tradition surviving from the 1930s was that of the slapstick, practiced by three devoted generations of the Korngut-Kemény family, the last of the Czech, Austrian, Italian itinerant puppet animators. According to Éva Hutvágner10 the Socialist regime effectively and probably intentionally prevented the family to build up a stable adult spectatorship: after the war the Keménys’ own permanent playhouse was nationalized and the family was not permitted to perform in Budapest any more.11 Even the name of their slapstick character, Vitéz László (László the Knight) had to be changed to the less aristocratic Paprika Jancsi (Johnny Pepper).

As a recent effort to bridge the gap between the puppet and live-actor, the child and the adult theatre scenes, the Budapest Puppet Theatre12 annually invites directors of significant renown to direct a puppet performance for adults. When Szikszai received the János Meczner’s invitation in 2018, he immediately responded positively: his recent works, Pillowman by McDonagh and later his Macbeth13 already used puppets to various extents in live-actor productions and live‑actor theatres, with remarkable success.

This time, however, his Shakespeare was to be puppeted throughout, and the venue, the Puppet Theatre only increased the difficulties. Szikszai had to make a production which, by the time it neatly unfolded, should persuade the viewer of the suitability of the puppet medium for adults. But he also had to immediately win his audience, not to allow the spectators to leave during the interval. Szikszai carefully delayed the appearance of puppets, and what he first did was create a storm, by an impressive strike:

I have bedimmed

The noontide sun, called forth the mutinous winds,

And ’twixt the green sea and the azured vault

Set roaring war; (5.1.50–53)

“The mutinous winds” (The Tempest, 5.1.51)

While the lights in the relatively small and cosy rehearsal room of the Budapest Puppet Theatre are dimming, and the spectators are casually awaiting The Tempest to commence, they cannot possibly imagine how far in time and space they will travel with Rémusz Szikszai’s rendering. They certainly might expect a stage storm of either the picturesque, the menacing or the playfully stylized kind. But probably few would believe that in the next moment they would mentally leave behind the reality of the uncomfortable chairs on the creaking grandstand of the Budapest Puppet Theatre’s shabby rehearsal room, the traffic jams and the pressures, the “slings and arrows” (Hamlet, 3.1.66) of everyday life, and suddenly travel to a parallel world, which is far in time and space, yet somehow flamboyantly real. Captured by the ethereal cries and whispers that sound creepy in the darkness, spectators are pinned to their seats, having lost their senses of time and location due to the blinding strikes of lightning created by a stroboscope. By the white flares we see sailing boats struggle against the waves, and soon we notice three female creatures who toss the vessels and animate the storm.

Figure 2. – The Storm in Shakespeare’s Tempest.

© Vera Éder.

Although warnings about the use of the stroboscope and the strong sound effects are pasted on both the playbills and the programme brochure, this blue‑lit stroboscoped storm is somehow uncanny and unexpected: it is more than a mise-en-scène, one has to make an effort to survive it, it seems almost unbearably long. It is a relief when Ariel, content with the job done, tunes it down.

Figure 3. – Gyöngyi Blasek, the oldest of the production's three Ariels, conjuring the storm.

© Vera Éder.

Figure 4. – Tamás Fodor as Prospero, directing the Storm in Shakespeare’s Tempest.

© Vera Éder.

Here, over the ocean’s literally silk surface, new and old stage technologies, represented by the stroboscope and the handmade, wooden boats, seamlessly fuse; the sound effects are re‑created live night by night (DJs: Bálint Bolcsó, Jázon Kovács). They all serve to effectively separate the travellers as well as the spectators from their well‑established past, acute problems, social positions, be they in Milan, Naples or Budapest. Shakespeare’s storm in Szikszai’s and his DJs’ production seems to be a practical spectacle to separate the characters in the first place, and an impressive stroke to unite the auditorium with the stage and wipe out all but the performance’s present. Indeed, it proves to be an indispensable device in order to suddenly invade and captivate the audience’s mind and turn their attention to the story on the stage in the ephemeral present, and to make them taste the “unique and unrepeatable” “event‑ness” of the theatre (Fischer-Lichte 41).

As the sea calms, the performing space slowly lightens and we start to understand the scenery and the proportions: the old man and the three women who fiddled with the toy‑sized boats are apparently playing Prospero and Ariel, and are flesh actors. The ribs of the giant wreck of a barge squeeze performers and spectators together, impressively extending the sense of union prompted by the common experience that has been achieved by the storm. The set for the 2016 Tempest of the RSC looks surprisingly similar; however, the impact, thanks to the particularly small performing space (that seats only 150 people, and thus is almost the size of a teacup), is completely different. The lack of physical distance between viewer and player simultaneously stimulates the spectators’ emotional involvement and at once reminds them of the meta‑theatre present in both the play and the production.

“Wonder and amazement / Inhabits here” (The Tempest, 5.1.114–115)

It is only after the shocking caisson of the mental and physical/optical storm that puppets appear. The wreck bathes in warm sunshine, and unseen, Ariels chirrup and sing as birds. A macaque’s playful gibber is heard from various locations—the three Ariels work wonders—, and soon a little monkey shows up, jumping on the ribs of the barge. No sooner than Gonzalo notes that “Here is everything advantageous to life” (2.1.52) the shipwrecked start chasing the first animal that had the misfortune of curiously peeping after them, thus breaking the spell of the paradisiac ambiance. The crudity of the attempt to catch and kill the jesting animal is both comedic and alarming: the scene revisits the moment when colonizers arrive in a newly found land and records the spontaneous and elemental drive to possess dead or alive whatever they find there.

Contrasting the depiction of the storm with that of 2.1, I intended to demonstrate how Szikszai’s minute reading makes use of the emotional rollercoaster Shakespeare offers in the text. Before we would realize it, Szikszai introduces the audience to the use of puppets, first with the wooden boats and now by making us feel sympathy for a particularly likeable, cute, big‑eyed animal of a baby’s size. Soon the fact that the monkey is a plushie animated by one of the three Ariels (though voiced by all three) and the fact that all the shipwrecked travellers wear some sort of a prosthesis (or body mask), holding what appears to be the plaster replica of their own heads, will seem perfectly natural and evident.

It is the storm’s magical work that makes us more interested than confused at the sight of the great diversity of puppets. Besides we are not disturbed but rather pleasantly surprised by a somewhat unusual tool that Piris calls co‑presence (30) of the puppets and puppeteers. Co‑presence in his sense however does not merely equal with the visible presence of the puppeteer (31).

[Rather, it] takes place between the puppeteer and the puppet and is particular in the sense that it establishes a relation […] between two things that are ontologically different: one is a subject (in other words, a being endowed with consciousness) and the other one an object (in other words, a thing). (30)

Following this logic, soon we are to understand the role of the costumes14 that are the same or quite similar for the animators and their puppets. For instance, both Miranda (Alma Virág Pájer) and her bunraku self wear a matching natural flax and linen outfit. Hoods, and what appear to function as hoodies have a purpose too: puppeteers at least partially cover their heads to drive the focus of attention away from their faces, indicating that they speak in the name of the puppet. By contrast, hoods are always off when actors speak without the puppet.

Figure 5. – Prospero telling the story of their close escape to Miranda (puppeteer Alma Virág Pájer) here under his full control.

© Vera Éder.

Figure 6. – Zsombor Barna as Ferdinand and Alma Virág Pájer as Miranda.

© Vera Éder.

Caliban’s (Zoltán Hannus) attire is another example of harmonizing the costumes and the puppets with the reading of the text: the savage who wears his heart on his sleeve and sings the beauty of the island in verse is differentiated from the rest of the cast by wearing his stick, a practical manly weapon, not on his sleeve but under his belly. He is the only one who, apart from Ariel and Prospero, does not have a puppet double. However, what he has, is a kind of penis sheath of an exaggerated size (half a meter) applied with rope ties onto his body in such a way that it seems to be a giant phallus. It later proves to be more than a funny piece of clothing: it characterizes and plays as well, in short, it is what theorists of puppetry call, after Frank Proschan and John Bell, a performing object (30). In this rendering Prospero severely “chastises”, that is, castrates the savage. Thus, when in a transparent box Caliban reappears without the stick tied to his body, he carries like a dead puppet his own giant phallus.

Figures 7–9. – Caliban (Zoltán Hannus) and his stick.

© Vera Éder (My editing).

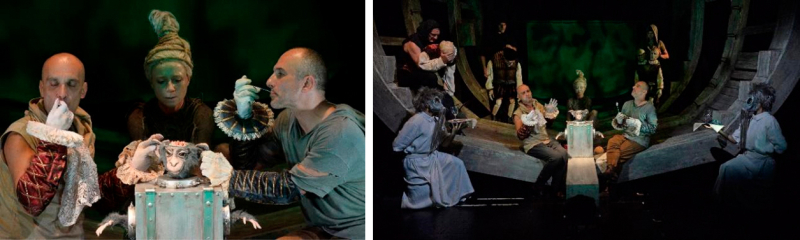

Despite the ostensibly chaotic diversity of puppets, a close look at the production reveals that Szikszai and his puppet designer Károly Hoffer apply them quite systematically. It is not the live‑actress but the child‑size bunraku Miranda who is the addressee of Prospero’s words in 1.2. It is also the bunraku girl who sights Ferdinand (Zsombor Barna). They are both dwarfed and also outnumbered by the power of Prospero and the tripled Ariels, all played by flesh actors. On the one hand, it is a physical and professional necessity; on the other hand, it is a metaphorical act that Ariels animate the wooden creatures’ motions. The bunraku’s head always belongs to its primary puppeteer while its limbs are often left to be moved by the (in)visible assistants.

Figure 10. – The two young Ariels, Anna Spiegl and Mara Pallai charming Ferdinand (Zsombor Barna) and his bunraki self.

© Vera Éder.

As Miranda and Ferdinand fall in love and start acting independently of Prospero’s charm, the bunrakus are replaced by the live puppeteers, an act that ought to be understood as more than a change of size; quite significantly and unusually in the theatre, it is a change of perspective. Szikszai and Hoffer stage a particularly moving scene when under the sway of their emotions Miranda and Ferdinand outpace Prospero’s intentions who then urgently slows them down by separating them with a magic glass wall. In live-actor theatres this spell is usually staged as invisible, actors merely pretend that they cannot move. Here Ariels physically fence off Ferdinand from Miranda’s body with a glass wall. The latter gains further meaning when, with an interesting change of point of view, we are to see the lovers as governable youngsters again, in their bunraku selves, the sad‑faced Ferdinand in a transparent box, just like a toy on old Ariel’s lap. The action on the (puppet) stage is thus capable of embodying the layers of the Shakespearean text:

“My spirits, as in a dream, are all bound up” (The Tempest, 1.2.595)

My father’s loss, the weakness which I feel,

The wrack of all my friends, nor this man’s threats

To whom I am subdued, are but light to me,

Might I but through my prison once a day

Behold this maid. (1.2.593–598)

Figures 11–12. – Ferdinand (Zsombor Barna) and his bunraku self temporarily paralyzed by Ariel’s (Gyöngyi Blasek) invisible charm.

© Vera Éder.

“This is as strange a maze as e’er men trod” (The Tempest, 5.1.293)

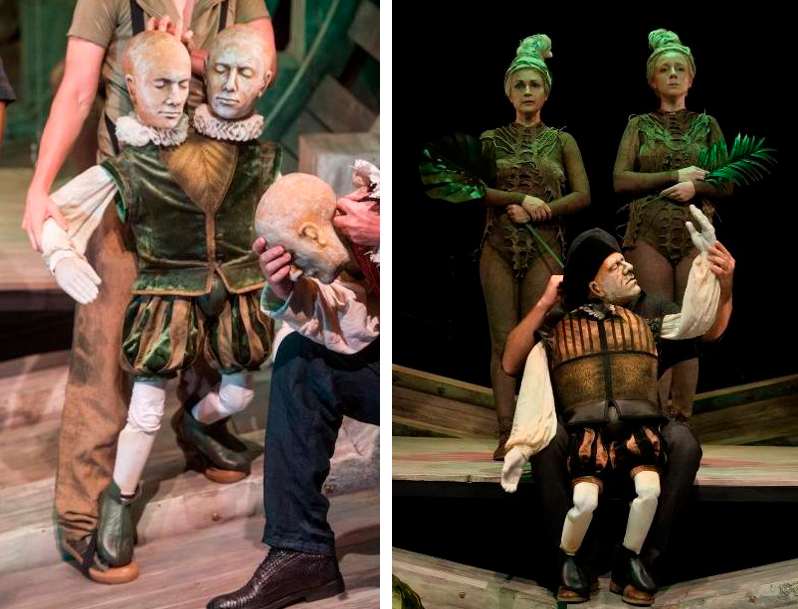

When we look at the variety of the prostheses Antonio, Sebastian, Alonso, Gonzalo, Adrian and Francisco wear, the sight might be slightly puzzling. The situation is further complicated by the three marionettes in the court masque and the rod/hand puppets of Stephano and Trinculo. Here, again, the analysis of the role of the puppets will assist us in understanding the profound effect they undoubtedly make.

One of the interesting solutions impossible on the only live‑actor stage is that Adrian and Francisco, the two courtiers “in attendance on Alonso”, are performed by the same puppeteer. The characters whose names, by no accident, we tend to forget, are not given clearly identifiable selves by Shakespeare’s text, hence Szikszai and Hoffer’s Gordian resolution. The small prosthesis strapped onto Tibor Szolár’s tall body visibly dwarfs the characters’ human stature, and laughably emphasises the two‑head and two‑mouth courtly parasite. The inherent irony is further heightened by the swift-paced moves of the pair with which they both spectate and react to the events. It is impossible not to recognize similarly bootlicking creatures [ADRIAN: “Tunis was never graced before with such a / paragon to their queen” (2.1.77–78)] in a country that is so rapidly sinking into the swamps of corruption.

Gonzalo’s almost life-size head and prosthesis stand in stark contrast to the two gilded leeches. In fact, while the sweet-tempered Gonzalo (Csaba Teszárek) delivers his monologue about his peaceful utopian state, the performer becomes nearly invisible: the “actual body of the puppeteer and the apparent body of the puppet” merge, as if the crust becomes one with the tree trunk, only to exhibit the sole true‑hearted court character.

Figures 13–14. – Tibor Szolár’s two‑head, two‑mouth court parasite, Adrian and Francisco, and Csaba Teszárek’s self‑identical Gonzalo.

© Photo by Zoltán Balogh, MTI Fotó.

It is a question whether the puppets personifying the travellers mentioned so far are rather illustrative and not sufficiently expressive of the Shakespearean text, and whether the lavish visuality of the puppet medium merely decorates or creatively furthers the claims of the drama. My response originates from “close reading” the prostheses and heads of Antonio and Sebastian: their representation certainly needs the contrast and the comparison that the other courtiers provide.

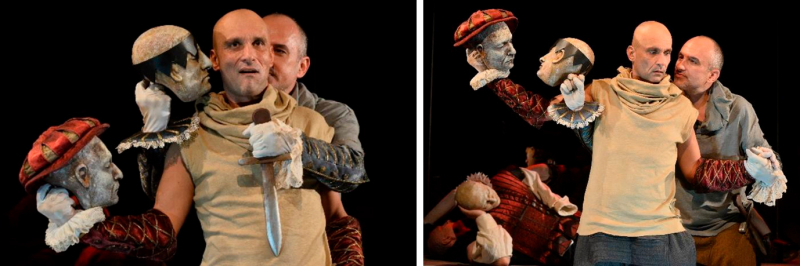

In Antonio and Sebastian’s case we can witness the intricate play which Paul Piris describes as the essence of co‑presence. According to Piris, “co‑presence inherently supposes that the performer creates a character through the puppet but also appears as another character whose presence next to the puppet has a dramaturgical meaning” (31).15 The actual arms of the puppeteers are clothed lavishly as if they belonged to the apparent body of the puppet. In contrast, the heads the puppeteers hold are quite lifelike plaster replicas of the puppeteers’ heads; and thus, while Antonio and Sebastian conspire, we see four heads altogether, one pair each. In sum, while the arms seem to indicate that the actual body of the puppeteer and the apparent body of the puppet are the same, the presence of the four heads effectively deny it. While not one spectator has the time to reflect upon this visible contradiction, the situation results in the desired effect: the sudden snakelike moves of the hands holding the heads evoke visceral reactions such as disgust and disdain in the spectator towards the plotting brothers. Moreover, doubling the speaking heads creates space for the director to repeat or counterpoint a situation. The dialogue between the two poker‑faced and threateningly lifeless replica heads demonstrates what one would see from the outside. The dialogue between the two real actors’ heads and mobile facial expressions demonstrates what is really in their minds (voilà, the dramaturgical meaning that justifies the puppeteer’s head next to the puppet’s head): “yet methinks I see it in thy face / What thou shouldst be” (2.1.228–229). While live‑actor theatre often uses asides through which the audience may peep into the character’s head, Szikszai’s solution subtly takes advantage of the mixed, live‑actor-and-puppet cast. The result—the two pairs of identical heads—is highly theatrical, meta‑theatrical and meta-puppet-theatrical at once. Its effect is nothing less than thrilling and menacing while also popular and tragi‑comedic.

Figures 15–16. – Poker-faced Sebastian (István Kemény) and Antonio (Norbert Ács) conspire uncovering their real selves.

© Vera Éder.

Because the sophisticated play with co‑presence dramatizes the double-faced, double-tongued nature of the scheming brothers, the only occasion when they take their masks off their poker-faced heads gains particular importance. In 3.3 Prospero reveals their wolfish and boundless power hunger, and when “Enter several strange shapes, bringing in a banquet” as well as illusory food, he tests the conspirators’ bravery: “Will ’t please you taste of what is here?” (3.3.55). In Szikszai’s rendering, the challenge is obvious: Ariel serves monkey brain. Usually a loud gush of shock sweeps over the audience at the sight of the boxed live monkey. Not too long ago we saw it bouncing happily on the ribs of the wreck, and now it first gibbers, then screeches in despair. Just for spite, Antonio and Sebastian take their time and spoon out what seems to be the monkey’s brain, munching loud with pleasure, to the frustrated laughter and utter disgust of the audience. Spectators report that they find the scene intensely painful even if they all know and see that the little macaque is a stuffed toy and that Ariel visibly voices it. Studies and articles16 have already explored how and why the ventriloquist trick works: simply because humans spontaneously look at what they suspect to be the source of a voice, a face or a mouth, because, due to our evolutional coding, we trust in the visual input better than in the auditory one. In sum, this explains why we perceive Ariel’s voice as the monkey’s screams, and consequently, why the monkey brain eating scene demonstrates the ultimate power of puppetry—on anyone, even on adults.

Figures 17–18. – The illusory feast for Antonio and Sebastian (István Kemény and Norbert Ács): the usurpers appear as ruthless colonizers.

© Vera Éder.

The least sophisticated puppets belong to the least serious characters, and yet again the question rises whether the puppet medium contributes to the better understanding of the play. Perhaps Caliban’s final punishment (his castration) would set his partners in crime, Trinculo and Stephano, the thin and the chubby, somewhat apart from the rest of the cast. However, through the devices of puppetry, Szikszai manages to keep them organically within his universe.

Trinculo and Stephano have puppet doubles of the simplest and most primitive kind: rod puppets which do not cover the puppeteers’ body at all. Much rather, these puppets epitomize and even exaggerate their personalities in the manner of the commedia dell’ arte. Stephano (Gergő Pethő), is depicted as a round-bellied simpleton: his puppet is a colossal wine bottle with a long neck, both of which serve Shakespeare’s low jokes (rejuvenated in contemporary Hungarian by Ádám Nádasdy). Trinculo, the thin one (Zsolt Tatai), “servant to Alonso”, is traditionally impersonated as the court jester, here he is personified by a rod puppet whose red cheeks, red hat and long red wooden nose remind us of either Punch or his Hungarian equivalent, Vitéz László / Paprika Jancsi (László the Knight / Johnny Pepper). By casting the Shakespearean jester Trinculo as Punch / Paprika Jancsi, Szikszai proves his familiarity with puppet traditions. The puppeteer’s acrobatic acting upside down or between his two legs points out what the Trinculo-character inherited from Punch (and/or Paprika Jancsi): his enduring optimism, his high levels of energy and his indestructible nature.

Tatai’s incredible athletic acting and his hairdo that pointedly resembles the dishevelled head of his Trinculo puppet provoke thoughts about co‑presence, more precisely, the vast (and disturbing?) complexity of the relationship between the puppet’s body and that of the performer’s. Tatai’s Trinculo is obviously informed about Shakespearean jesters, such as the carefree loudmouth Falstaff, or the wise and occasionally melancholic fools, like Feste. The puppeteer with frequent comically honest asides represents the unhappy self behind the shrill voice of the red-nosed Punch. Thus, by adding a melancholic touch, Tatai creates a profoundly detailed, memorable fool.

Figures 19–20. – The two unsophisticated characters of the comic drunkard and the Elizabethan court jester / Punch / Paprika Jancsi performed with simple rod puppets: Gergő Pethő as Stephano and Zsolt Tatai as Trinculo.

© Vera Éder.

“No more amazement” (The Tempest, 1.2.15)

The analysis of the relationships between the puppets and their animators in Szikszai’s staging of The Tempest must conclude with the queen of all puppets, the marionette. It is the most elegant and most gracefully moving creature and also, the most difficult one to handle: reportedly only a lifetime is enough to master its strings. Thus, when seeking the worthy representation of an early Baroque court masque it was only natural from Szikszai to choose the marionette. In general, as Margaret Williams put it, the marionette is “the classic metaphor of puppetry—the godlike puppeteer both gives life to and withdraws it from a creation made in his/her own image. […] It demonstrates, quite literally, that the puppet’s ‘life’ exists only as an effect of the puppeteer’s control” (18).

Figure 21. – The charming court masque / Baroque opera performed with marionettes—the legs of the Ariels, of Anna Spiegl and Mara Pallai who sing as Ceres and Iris respectively, are visible on the opposite sides of the miniature barge.

© Vera Éder.

Szikszai exploits both the concept and the ambiguity of the marionette entirely: the marionettes are to play the role of the three goddesses, Iris, Ceres and Juno, who are moved by the three female Ariels, who are, in turn, moved by Prospero. In centre stage we see a rather small replica of the barge which is tiny enough for the marionettes to appear as goddesses. While we focus on the opera-singing marionettes, we almost forget about the frightening proportions:17 about the fact that the marionettes reach only to the Ariels’ knees and that their reality on the tiny wreck is no more than a coloured set in a miniature theatre. Although marionettes are famous for their capability of ballet dancing and for taking unreal moves, it becomes clear that even the most elaborate marionette is inherently limited: it can walk, in fact, toddle along the plank of the barge, but can never exchange places with another. It is technically impossible as their strings would get entangled for ever. In this way, the situation of Szikszai and Hoffer’s marionettes is similar to that of their manipulator, Ariel: no matter how omnipotent, charming or artistic Juno, Ceres and Iris or Ariel seem to be, they remain equally dependent upon their master.

As his last magical action Prospero sets Ariel free with a kiss, and promptly the pretty Ariels disappear from his embrace. Instead, an old hag sporting a well‑worn, colourless brown sweater smiles up at Prospero. He faces the sudden lack of the skin‑tight dresses, the much younger bodies. Ubi sunt—where have they (his puppets) all gone? Or did he merely dream them? But “Let us not burden our remembrances with / A heaviness that’s gone” (5.1.236–237).

Figures 22–23. – Taking off the masks—taking leave.

© Vera Éder.

Conclusion—mere oblivion?

Just before the Epilogue, in the “last scene of all, / that ends this strange eventful history” (AYLI, 2.7.170–171) the characters gather at Prospero’s summons to give up playing. In Szikszai’s rendering the actors’ detachment from their roles takes place in silence and with heart-rending dignity. Puppeteers separate from their puppets: they slowly peel off their prostheses, gently lay down their replica heads, rod puppets, performing objects and their bunraku selves. By peeling off one layer of theatricality we sight the next: they are like us, merely players.

This scene effectively prepares us for the Epilogue, heightening tension for the theatricality of the moment when Prospero must step off. He has “pardoned the deceiver”, he has set free the creature whose strings he used to move and now he must see what strength he has as his own … His initial thirst for revenge and vehemence to act have melted into acceptance and reconciliation. Although evil brothers will remain evil brothers, heaviness is gone, grievances ventilated, vexations articulated—all by role play, by the power of animation, by the magic of the theatre.

Puppeteers do not act any more—this is how puppets (never) die. With them we will lose the playfulness of their self-referentiality, their emphatic fictitiousness, their ever conspicuous embodiment of a theatrical role and the inherently (meta)theatrical nature of a puppet and live‑actor performance. With them we will lose the ventriloquist trick, we will stop the experiments with the changing point of view and the double focus, we will lose all that ensured an inventive and gripping reading of The Tempest. It is the performance critic’s responsibility, as Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine pointed out (78), to select truly worthy renderings for the critical discourse, and I firmly believe that Szikszai’s engaging puppet and live‑actor production is one of those. “A grace it had. Devouring” (3.3.103).

The lights are dimming, Prospero remains alone in the space surrounded by the audience, his fellow actors and the puppets. This is his last job. He has neither a puppet, nor a mask. In the last minute even the heap of puppet corpses is gone. What he only has is a bunch of former puppeteers that now become his audience. Szikszai makes sure that in the Epilogue the actor’s loneliness with his role is almost tangible. Before he can bow and suck up the praise like Stoppard’s Player, “Oh, come, come, gentlemen—no flattery—it was merely competent […]” (123), he must answer the ultimate challenge, he must reveal the power of a live‑actor’s death scene.

By staging Prospero’s death Szikszai makes us suddenly realize that the Epilogue of The Tempest might not be only about the enthusiastic applause of an already tamed audience: much rather, it is about the loneliness of the long distance runner, of the experienced theatre professional, who will have to play the way he has never felt and who will have to go further than he has gone ever before. Thus, in Szikszai’s production the Epilogue of The Tempest demonstrates what the actor faces professionally: the difficulty and the risk night by night, and the arrival to the “undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveler returns” (Hamlet, 3.1.87–88). Leaving his leading actor so gradually and also so spectacularly alone, in the crossfire of gazes by spectators and colleagues alike, Szikszai responds to Shakespeare’s challenge and demonstrates what theatre really, viscerally is. The last scene of all—though perhaps sans everything—is not “mere oblivion” (AYLI, 2.7.173): taking off our masks, holding our breaths, we are all gathered to see and to remember how death is performed by a great theatre professional.