Set against the backdrop of the climate crisis, the poems of Ellen van Neerven, Jazz Money, and Evelyn Araluen expose the violence of colonization and interrogate past, present and future Australia with an insightful First Nations’ eye. Widely acclaimed recently, these three young poets are often seen as inheritors of the environmental activist poetry of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Kevin Gilbert, Lionel Fogarty1, and Alexis Wright. First Nations poetry remains peripheral to the mainstream Australian literary market despite significant publications and associated activities which gained visibility with the advent of social media.2 Yet, contemporary First Nations writers represent a dynamic ingression as they go on the attack against modern Australia’s myth-making and continuing politics of domination that are perceptible in its history, literature and relations to the land.

The poems gathered in Dropbear (Evelyn Araluen, 2021), How to Make a Basket (Jazz Money, 2020), and Throat (Ellen van Neerven, 2020) address a wide range of subjects related to ecological concerns in the wake of the devastating 2019–2020 bushfires that swept across the territory. Inevitably, some First Nations people’s lands that were passed down from generation to generation, through songlines, languages and kinship networks were affected. Their works also explore how First Nations people are positioned within a landscape that has been eroded by settler colonialism, unfairly occupied, and reshaped through colonial toponymy.

Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith in her influential work Decolonizing Methodologies examines how colonialism has shaped Western ways of thinking and research methods. She argues that knowledge production needs to be reoriented to center Indigenous perspectives, values, and goals. For Smith, decolonization means reclaiming and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge systems, languages, and ways of living. It is an effort that challenges the very foundations of colonial power:

The acts of reclaiming, reformulating and reconstituting Indigenous cultures and languages have required the mounting of an ambitious research programme, one that is very strategic in its purpose and activities and relentless in its pursuit of social justice. (Smith 142)

In the context of Australia which is a settler-colony built on frontier violence and the systemic erasure of First Nations knowledges, Smith’s approach invites a reconceptualization of place, not as a geographic location defined by colonial cartographies, but as a relational nexus embedded in memory, kinship, and responsibility. She foregrounds the need for epistemic justice: the validation of Indigenous ways of knowing, doing, and being that have been systematically silenced or co‑opted by colonial processes. Her work therefore offers a powerful lens through which to read the poetry of Ellen van Neerven, Jazz Money, and Evelyn Araluen, whose texts resist settler-colonial narratives not only by exposing environmental degradation but by asserting Indigenous sovereignty, epistemology, and ontological difference.

The present article also draws on the Aboriginal concept of Country which is powerfully articulated by Deborah Bird Rose in her influential work Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness. She describes Country as a living, relational entity sustained by reciprocal relationships between people, non‑human beings, and ancestral forces. As she writes, “Because of this richness, country is home, and peace; nourishment for body, mind and spirit; heart’s ease” (Rose 7). In Aboriginal epistemologies, Country is a sentient presence that participates in the production of meaning, memory, and story. It is a co-creator of life and knowledge and dynamic site of interdependence, challenging colonial understandings of land as inert, vacant, or disconnected from life. Building on this relational approach of place, it is undeniable that literature plays a critical role in reconfiguring our ways of inhabiting the world.

Considering its colonial past and the ongoing contestation around belonging and placeness, Australia offers a significant site for decolonial ecological inquiry. Indeed, the country’s environmental policies and narratives have often been shaped by settler-colonial frameworks that perpetuate the dispossession of First Nations peoples and their knowledges. Mainstream environmentalism in Australia (and globally) is frequently embedded in Western epistemologies that abstract “nature” from cultural, spiritual and ancestral relations to land. From a decolonial perspective, this model of environmentalism is not only limited but hegemonic as it reproduces the logics of extractivism and settler futurity. Such epistemologies allowed to maintain settler access to land and cultural erasure through apparently benevolent environmental projects and inevitably led to the marginalisation of traditional ecological knowledges. It also reinscribed colonial hierarchies, especially when First Nations’ voices are co‑opted or silenced within environmental discourse. In this light, the problem is not merely ecological degradation, but epistemic violence that denies alternative epistemologies and ontologies of land and life.

In this respect, the poetry of van Neerven, Money, and Araluen offers a vital intervention. While these authors do not identify as environmental activists in the conventional sense, their work participates in a global movement which Canadian First Nations scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson defines as a “project of resurgence” which is a deeply grounded, community-based process of cultural, political, and ontological renewal rooted in First Nations’ knowledges and land‑based practices. For Simpson, resurgence is not a reaction to colonial violence, nor is it framed as a pathway toward reconciliation or integration within settler institutions. Rather, it constitutes “a radical and complete overturning of the colonial structure of dispossession” (Simpson 10), aimed at regenerating First Nations’ presence and autonomy on terms that are not dictated by the settler state. Through this lens, the poetic interventions of van Neerven, Money, and Araluen can be seen as articulating alternative modes of dwelling and knowing that resist both the material exploitation of land and the discursive erasure of First Nations sovereignties. Their work offers powerful acts of reclamation of place, but also of narrative, temporality, and epistemology. For instance, in her poem “To the Parents”, Evelyn Araluen directly rejects the liberal framework of reconciliation and the settler narrative of irreparable rupture, demanding instead: “No reconciliation. No rupture. Just home” (Araluen 2021, 87). This call for continuity and presence responds in part to Alexis Wright’s question in an article published in The Guardian in 2018: “How do you find the words to tell the story of the environmental emergency of our time?” The issue raised in the whole article is clearly linked with epistemological authority: whose knowledge is recognized as legitimate, and whose histories are permitted to shape the discourse of ecological crisis?

Drawing on First Nations epistemologies and relational understandings of Country, this article examines how the poetry of Ellen van Neerven, Jazz Money, and Evelyn Araluen contests dominant (neo)colonial notions of place and environmental thought. Their work challenges the universalizing logic of mainstream environmentalism and rejects extractivist ideologies rooted in colonial dispossession. The analysis also adopts a dual perspective by reading their poems both as expressions of Indigenous ecopoetics and as decolonial acts that resist settler narratives and assert First Nations presence and sovereignty.

Getting rid of the colonial oikos3 and letting the Law and the Dreamtime resurface

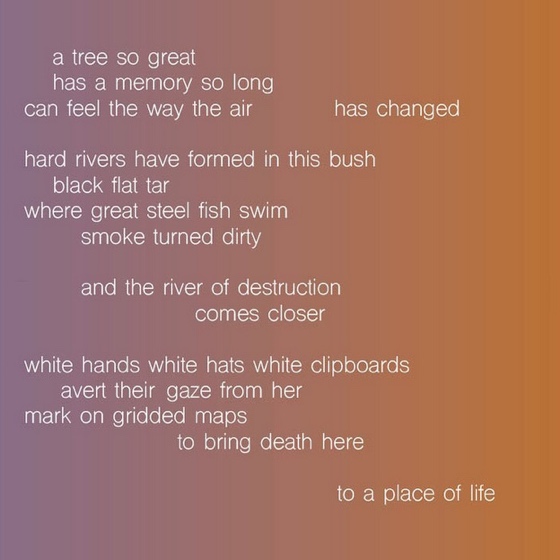

2019 and 2020 were the worst years on record for the planet, and the bushfire seasons that Australia experienced illustrate this unprecedented crisis. According to the Australian Public Service Commission, the tolls rose to 33 human deaths, more than one billion native animals and plant deaths, 113 species threatened with extinction. 5,900 buildings were destroyed including over 2,800 homes and sacred sites. In two years, over 18 million hectares were burnt. These figures show how catastrophic in scale and impact these fires were both for the people and for nature. Despite First Nations people in New South Wales and Victoria only representing 3.4% of the total population4 they had greater exposure to bushfire smoke because of poor living conditions and lack of support from the government. First Nations peoples, including children, experienced trauma and developed respiratory issues. Yet, bushfires have always been a feature of the natural environment in Australia, and in the past, Indigenous cultural burning may have helped reduce the intensity of fires. For thousands of years, First Nations peoples nurtured and protected their country, but brutal invasion and the destruction of resources drastically altered the ecosystems in a short time and profoundly impacted practices of land management. Furthermore, sacred lands are still being destroyed by state government as was the case in October 2020 when direction trees (which are sacred trees that carry the spirits of the ancestors) were cut down to build a highway in Western Victoria. This event is evoked by Jazz Money5 in “Sweet Smoke”, the opening poem of their debut collection How to Make a Basket. Also posted on their Instagram account, the author expresses their grief at the loss of their country; and calls for social and climate justice:

Figure 1. – “Sweet Smoke”, posted on Jazz Money’s Instagram account (October 2020).

The final line (“to a place of life”) points to the colonial tendency to perceive certain environments as lifeless, ignoring the living presence and significance of these places within First Nations ontologies. In reality, these were and remain sites of complex ecological and cultural life, many of which continue to be destroyed despite growing awareness of the climate crisis. Yet, the poets do not limit themselves to depicting loss. Their work also challenges the logic of capitalist greenwashing by exposing how environmental rhetoric is often used to mask ongoing extractivism. Crucially, their poetry invites us to reconsider what it means to destroy a place. The felling of a tree, within First Nations frameworks, is not a neutral act. It can signify the erasure of a relational and storied space. In this sense, the destruction of non‑human beings like trees is inseparable from the destruction of place, as these beings are integral to the living networks that constitute Country.

In “PYRO”, Evelyn Araluen also considers the 2020 bushfires as she writes from a desk “COVERED IN ASH” from her “THRICE-BURNT CHAR OF HOMELAND”. This poem, which seems to mimic a news bulletin or a tweet, is a capitalized text denouncing the irony and hypocrisy of the Government who constantly boast they will solve the environmental crisis: “/ SCOTT MORRISON SITS SANGUINE IN A WREATH OF FRANGIPANI // […] // AGAIN AGAIN WE ARE TOLD TO BE GRATEFUL FOR THIS GIFT AS IF THE MACHINE HAS FIREPROOFED ANYTHING BUT ITSELF //”. And while First Nations people are at the forefront of the ongoing ecological crisis, ministers merely keep on changing suits for their official meetings as Ellen van Neerven deplores in their satirical poem Politicians Having Long Showers on Stolen Land. However, while fire can lead to major human, species and habitat loss, it can be a source of restoration when it is managed by First Nations people.

In this respect, the three selected books resonate with what poet and CHamoru scholar Craig Santos Perez conceptualizes as Indigenous ecopoetics. Perez defines his approach as one that examines literature as a vital space for expressing Indigenous identity and environmental belonging. In Navigating CHamoru Poetry, he writes: “I root my analysis within the scholarship of Pacific, postcolonial, trans‑Pacific, and Indigenous ecopoetics to demonstrate how literature that focuses on the environment is an important site for articulating Indigenous identity” (Perez 42). He explains that Indigenous ecopoetics foregrounds themes of interconnection between humans, non-human species, and the land and that it considers water and territory as foundations of Indigenous genealogy, identity, and community. Moreover, it interrogates colonial and capitalist representations of nature as inert and commodifiable, using ecological imagery to challenge extractivist paradigms. Finally, Indigenous ecopoetics restores a sense of sacred relationality with the Earth, conceptualizing land as ancestor, healer, and site of resistance, care, and belonging.

The three poets studied here carry these principles in their writing. Their poems are rich with ecological images and ancestral metaphors that indict Western exploitative attitudes. Interestingly, they also push Indigenous ecopoetics in more overtly political and formally experimental directions. Indeed, van Neerven, Money and Araluen refuse conciliatory narratives and directly confront settler-colonial structures of power. While the poems certainly seek to heal wounds of the past and care for Country, they pointedly withhold any facile reconciliation with colonial history. The lands they evoke are, as Araluen writes, “drenched in a history of settler violence” (Araluen 2021, 6); a reality that no amount of nostalgic pastoral sentiment or folkloric romanticism can paper over. In place of settler-centric “green” narratives, these poets demand truth-telling and uncompromising resistance, making their art a site of decolonial witnessing rather than a peaceful resolution.

Australian scholar Amanda Johnson observes in her article “Writing Ecological Disfigurement: First Nations Poetry after ‘the Black Grass of Bitumen’” that today’s First Nations poetry critiques “proleptic environmental mourning, simplistic environmental apocalypticism and compromised visions of political reconciliation” (1). Johnson points out that Araluen (and her peers) condemn tokenistic6 “greening” efforts and reconciliation rhetoric that fail to restore Indigenous sovereignty. She also highlights Araluen’s metaphor of “potplanting in our sovereignty”, which encapsulates how settler society tries to “embellish and fix” colonial realities by grafting Western concepts (plants, laws, culture) onto Indigenous land without ceding real power. By invoking the absurd image of a potted plant in sovereign ground, Araluen ridicules reconciliation efforts that do not uproot colonial power. In this light, the work of Araluen, Money, and van Neerven shifts the conversation from reconciliation to reinvigoration. Through linguistic, spiritual, and ecological practices, they offer reclamations of time, of space, of language, of relation.

Besides, through the praxis of poetry, the three poets evoke certain overlooked practices about land management to revive and promote land‑based knowledge and relationship with their ancestral land. Storytelling and orality are part of that revitalization. Moreover, for them, environmental destruction and social oppression have equally affected their habitat, a hypothesis which is notably found in Ghassan Hage’s 2017 book Is Racism an Environmental Threat? The critic sums up his own studies in the following terms:

In my book Is Racism an Environmental Threat?, I argue that ecological crisis and racism are both grounded in what I have called “generalized domestication”: a mode of dominating and exploiting nature and people. I offer a critique of generalized domestication, and I highlight the existence of other modes of relating to nature and to each other […]. (Hage 2021, 188)

In Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World, civil and environmental engineer and political scientist Malcom Ferdinand also defines the concept of colonial oikos as a violent way of inhabiting the Earth; a mode of dwelling based upon ownership, extraction, and control, whose devastating impact affects not only the environment but also societies worldwide. This is the reason why he feels ecology should replace environmentalism in taking into account political and social aspects as well. In “Why We Need a Decolonial Ecology” Ferdinand points out that our way of tackling climate change is too restrictive and eludes other aspects:

[…] Talking about ecocide, for example, creates an intergenerational fabric (we connect our actions to the lives of our children, we take responsibility for our legacy, we negotiate that of our parents), but this fabric is thought about in environmentalist terms, rather than social and political ones. (Ferdinand 2020)

In other words, climate change should be envisaged as a social challenge as much as a scientific challenge. Indeed, anti‑racism, anti‑colonial, feminist and environment movements have all highlighted the dominant structures of modernity. The issues these movements are facing lead them to reconsider the Western mode of experiencing the world including interactions with human and non‑human communities. From that assumption, Ferdinand conceptualizes a decolonial ecology that holds protecting the environment together with the political struggles against (neo)colonial domination, systemic racism, and misogynistic practices. Although the three poets do not formally align with Ferdinand’s framework, their poetics echo several of its central claims and especially the critique of Western ontologies of control and their refusal of settler-environmental paradigms. Indeed, their poems seek to eschew simplistic views on environmentalism imposed by the knowledge system of the West that will only focus on one place of dwelling on Earth. They also refuse a unilateral ontology that is based on domination, the exploitation of the land and of First Nations Peoples.

The three poets follow a decolonial pathway: a return to the oikos corresponding to a Global South perspective. This change in paradigm means not only to be open to alternative forms of structures, practices, or belief systems, but also to explore liminal spaces, new modes of signification and poetic effects by interweaving genres to develop relational narratives in which places are no longer settings but actual topics in their poems in the sense that places and the land can perceive things and have an agency of their own. As Alexis Wright observes in her 2018 essay “Hey Ancestor!”, what Western thought might term the oikos is known to First Nations as Country; an “inter‑woven law country” wherein land and Law are one and the same. In Wright’s words, the true measure of sovereignty is the collective responsibility of caring for that living land: “That’s real sovereignty kind of thinking. True ownership. Comes with responsibility. Caring. Respect” (Wright 2018). She also emphasizes that sovereignty is not a matter of legal title or a National Day of Celebration, but an everyday commitment to uphold the Law of the land. This insight resonates deeply with the poetry of van Neerven, Money, and Araluen, who treat Country as an agentive participant in their writing. By explicitly invoking Wright’s concept of “real sovereignty” grounded in Country, the three poets reinforce a decolonial understanding that the environment is not a passive space but a source of law, history, and spiritual truth; a living entity to which humans owe reciprocity and respect.

Re‑planting First Nations’ connection to the land

In her book Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law, Indigenous Australian Professor of Law Irene Watson provides a compelling Indigenous framework regarding the notions of place. For her, land is not property but a living being, and place is not a fixed point but a continuous relation of obligation, spirit, and memory. Watson also articulates a vision of land and law that is inherently relational, spiritual, and processual:

Raw Law is not written. It is lived. It is the first law, the law of land, of relation, of obligation, of memory. It is embedded in Country, in the way we speak, walk, relate, and exist. It is not located in time the way the white law is. It does not need to be made visible to be valid. (Watson 23)

Her concept of “Raw Law” emphasizes that law is not imposed but lived, originating from the land itself and the relationships it fosters. Another foundational notion in many First Nations cultures of Australia that informs this ontological and epistemological grounding is the Dreaming. This concept constitutes a dynamic relational system, where every element (human, animal, landscape, or ancestral being) is involved in a network of reciprocal obligations and presences. Not only does it refer to ancestral creation stories, but it continues to shape responsibilities and modes of being in relation to Country, thereby linking land, law, and knowledge in a non-linear temporality.

In “The Waking Desert: When Non‑Places Become Events”, French anthropologist Barbara Glowczewski explores how Indigenous ontologies see desert places as “sites of becoming” instead of unproductive “non‑places” only valuable as places of possible extraction of “fossil fuels” and “mineral deposits” (4‑5). This mode of relation undermines the extractivist rationality that instrumentalizes land as property or resource. It echoes Malcom Ferdinand’s concept of “decolonial ecology”, which challenges the colonial oikos by proposing an ethics of cohabitation grounded in responsibility and interconnectedness.

Since the early 2000s, relational epistemologies have emerged as critical alternatives to Eurocentric paradigms, especially those that frame land through notions of ownership and objectification. Scholars such as Linda Tuhiwai Smith or Leanne Bestasamosake Simpson have foregrounded Indigenous knowledge systems as rooted in embodied relationships with land, memory, and kin. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems are rooted in relational ontologies in which Country is a sentient presence, an agent of memory, meaning, and story.

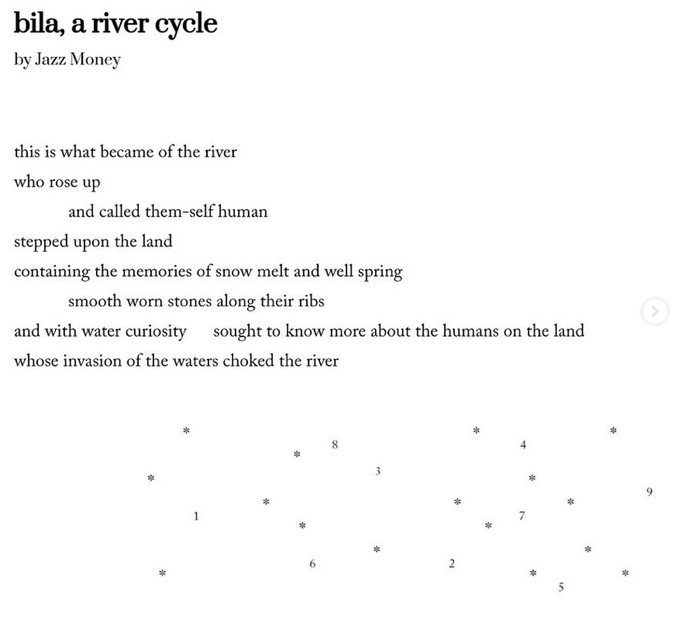

Similarly, in Dropbear or in How to Make a Basket, rivers or inland seas are provided with an agency and sentience which connect both human and non‑human entities. Sometimes, the agency of the country itself withholds a possible reconciliation between the settlers and First Nations people as “the water carries immemorial, a river without peace will not let you pray” (Araluen 2021, 84). Thus, a resisting force arises both from people and nature to oppose any trace of the modern world’s hold as well as the relentless structure of settler-colonial violence. This defiance is also manifested in the structures of their poems which are characterized by repetitions, patterns and loose punctuation. In bila, a river cycle, Jazz Money uses mislineation as well as a sort of bio‑mimetic technique to go beyond the metaphor and defy the Western conception of space and ways of inhabiting the Earth in the image of the colonial oikos:

Figure 2. – “Bila, a river cycle”, posted on Jazz Money’s Instagram account, January 2021 (How to Make a Basket, 59).

Here, the lines are stretched to suggest the continuance and cyclical renewal of the bila/river (situated in Wiradjuri country) that is not used as a picturesque background but more as a place for connection in an act of meaning-making. The environment is read as the ground of spiritual and cultural belonging. Most importantly, the water resurfaces, rises up to confront the settlers and their impacts upon the land. The poem also sweeps across the page, breaking on its way its expected linearity and its own finality (its telos) with the absence of punctuation and the abrupt run-on-lines in improbable places. This is all the more striking as the stars/asterisks themselves are once again somehow disrupted by the mysterious adjunction of numbers with no apparent order, hierarchy or logic. So in such a short poem, there is both the resurfacing of the Dreamtime and its inherent harmony and flow, and the sense of an unaccountable disruption whose impact is still difficult to assess, the human “invasion of the waters” which “choked the river”. Interestingly, Jazz Money somehow reclaims the dual and original significance of the word bila, which both refers to the Milky Way and a pool of water that is cut off from the river.7 The incorporation of the worldview of the Dreaming signals the presence of resurgence through reconnection with ancestral narratives. Beyond the aesthetic and symbolical aspect, the evocative topography of the poems that is found in the poets’ collections attempts to mimic the diversity of their country which is marked by layers of imposed colonial toponymy, interrupted transmission, and contested meanings. For these young poets, the landscape is fragmented by historical violence and cultural dislocation. The settler naming of places remains a powerful tool of domination, obscuring First Nations’ presence and undermining relational modes of knowing. It is a remnant of the colonial oikos that forced First Nations people to “dress in translation” (Araluen 2021, 10) meaning that their identity is expressed through the imposed language of the colonizer for it is “hard to unlearn a language, to unspeak the empire” (Araluen 2021, 8). These two lines suggest both constraint and disguise: to speak in English is to adopt a form that conceals or distorts the original voice, shaped by relational ontologies and Country. Yet the metaphor also carries an ironic charge, hinting at a strategic performance—a way of navigating and unsettling settler discourse from within. In this sense, Araluen’s poetics expose the tension between linguistic survival and resistance, making visible the limits of colonial language to fully carry First Nations knowledge and memory.

But even though the authors can only talk back to their oppressor in English, they question the transplanted language and parody it with the use of fragmentation, satire and puns. By including words and phrases from Yugambeh (van Neerven), Wiradjuri (Money) and Bundjalung (E. Araluen), the authors reject the language of the colonizer and demonstrate how sometimes re-learning a lost language is a way to return to their own oikos and place, to find their entire identity by reclaiming it. Undeniably, the use of First Nations languages in poetry allows to reassert the ontological relation between language and country, as James Tully suggests in his article “Reconciliation Here on Earth” when he notes that language is not separate from nature—it has an interdependent and reciprocal relation with it instead.

Recently, Australia adopted dual names for cities as an attempt to restore First Nations place naming as Calla Wahlquist explained in her 2022 article “The Right Thing to Do: Restoring Aboriginal Place Names Key to Recognizing Indigenous Histories”. Some projects invite First Nations people to share the story behind their place names. Activist and writer Bruce Pascoe for instance supports this decolonizing process as it helps to unlock past stories and First Nations narratives which are essential in acknowledging both their sovereignty and their connection to Country. The Dreamtime and songlines provided a set of blueprints for each living or non‑living form and numerous place names refer to animals, plants and the features of sacred sites. In other words, First Nations peoples created toponyms corresponding to stories of past events that are still re‑actualized in the present by way of practices that do take place, rituals that celebrate them, and the dreams that visit the local people.

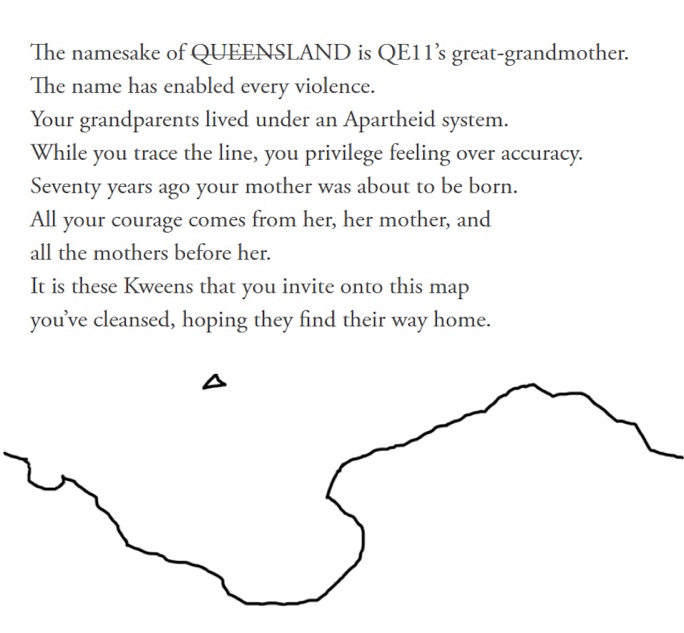

First Nations territories should be respected for their specificity and unique signification and language, and their sacred dimension revitalized through ritual for “language is empty without ceremony” (van Neerven 28). However, renaming places is not self‑evident. The linguistic reconnection is a persisting struggle that will require adaptabilities and will unsettle the Australian toponymic system, for even if First Nations’ placenames have survived the onslaught of British annihilation of Indigenous languages and cultures, many Australians are not aware of their meanings or origins. In relation to that situation, in 2021 van Neerven wrote three unreleased poems which can be found on the website Red Room Poetry.8 They were part of a larger project called Kweensland: Sovereign Bodies and the Colonial Nation-State. The second poem (“Kweensland. 2.”) takes a keenly acerbic look at the colonial toponymic heritage and by erasing the word Queen, van Neerven points out that renaming and/or misspelling a place is no longer a tool of the oppressor. Naming a place is not a neutral practice, it has a political dimension as it imposes a specific imaginary. Once again, the typography plays a significant role and embodies decolonial praxis by focusing on First Nations ancestry, resistance and sovereignty.

Figure 3. – Ellen van Neerven, “Kweensland. 2.” (December 2022).

In the third poem, van Neerven spells out her critique of mapping and place naming, making the settler readers’ sense of placeness challenged. The final lines offer words of resilience and resistance to First Nations readers: a new perspective of inhabiting the lands by revitalising their culture to regain their sovereignty: “To place is not to perfect / To stay, to keep on, is something we must do.” With this poetic project, van Neerven explores the impact of performative naming which annihilated First Nations communities. By erasing and miswriting words in the first selected poem, the poet challenges the settler’s logic of mapping that dictates what must be visible and what should remain concealed, what is considered as legitimate presence and what is cast as marginal.

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous scholars and artists have invited us to rethink mapping not as an act of possession but as a practice of relation and responsibility. Mykaela Saunders, in “The Land Is the Law: On Climate Fictions and Relational Thinking”, shows how Aboriginal songlines, literature, and art function as spatial practices that conserve and revitalize Country through memory, ceremony, and kinship: “Our songlines—which form the oldest continuing transnational literatures—are designed to conserve Country through human stewardship, and to revitalize it through ceremonial activation” (23). From this perspective, mapping becomes an expression of care and accountability rather than control. It is an ethic that resists the settler colonial gaze and affirms enduring responsibilities to ancestral places. It also acknowledges that Country is both a sovereign land and a living network to which First Nations belong and from which they derive their identity and responsibility.9 This implies that maps must be decolonized, and that cartography should become an epistemological practice that includes a different relationship to Country. The selected poems testify to this transformative and decolonizing ecopoetics that contemporary First Nations poets work to craft. Through subversive language and inventive poetry, these texts materialize a deep resurgence in First Nations’ culture and knowledge to protect their lands, to defend their cosmogonies (which acknowledge the place of non‑humans in the world and ask for climate and social justice). The concerns about the dispossession of First Nations peoples and land exploitation account for the incorporation of decolonial theories in First Nations’ ecopoetics. As both humans and non‑humans face ongoing changes in their lives and landscapes, displacing the colonial worldview that forged hierarchies between races, genders and lands is a necessary step to strategize renewal and continuity within First Nations communities.

There is, however, a fundamental issue: how, in practical terms, can these First Nations writers’ poetic praxis prepare the ground for other possible relations between the land, the people, the plants, and the spirits? Can it facilitate the resurgence of alternative imaginaries in view of tackling the current ecological crisis?

Decolonial ecology: is it only a symbol or a metaphor?

In “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor”, published in 2012, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang argue that decolonization should become a radical project that cannot be reduced to metaphorical or symbolic acts. Unlike numerous approaches that tend to define decolonization as a shift in culture or pedagogy, they insist on its material and political dimensions—a message that clearly resonates in the works of Ellen van Neerven, Evelyn Araluen, and Jazz Money. Indeed, caution must be exercised when using the term “decolonization” as its meaning could be co‑opted by non‑First Nations and could ultimately undermine its goals. The three poets are fully aware of that pitfall since their poems expose how such acts of appropriation perpetuate colonial harm and erase First Nations’ agency. With regards to that, even if Evelyn Araluen’s poetry aligns itself with decolonial ecopoetics, she raises the issue that First Nations’ writers might “[…] run the risk of foreclosing decolonization to an academic elite by coding it purely within poetics and academic practice” (Araluen 2017). Indeed, in the absence of activism or direct environmental action, the theory may remain purely metaphorical. In her poem “Breath”, Evelyn Araluen pointedly asks, “What use is a poem in a museum of extinct things, where the Anthropocene display is half-finished?” (Araluen 2021, 77) which serves as a self‑reflexive question about poetry’s efficacy concerning ecological collapse. This remark finds a sharp parallel in Ellen van Neerven’s satirical poem “ecopotent”, which refuses to participate in ecopoetics when it is no more that sheer “ecopornograph[y]:

Dugai asks me

To pen poems

For ecopoetics journal

whatttttt you think words will save trees?

[…] label your art ecopoetic

I think it really is

Ecopornographic

Just call me ecopessimistic

Kick me out of the conference

(Van Neerven 66)

By voicing such skepticism, both Araluen and van Neerven underscore the political limitations of poetry (and scholarly discourse) as vehicles for ecological action. Van Neerven’s satire and critique are strongly felt in “ecopotent” which concludes by an anonymous person advising the poetic persona to write poems that could be labelled “ecopoetic” even though they themselves consider such type of poetry “ecopornographic”—a biting indictment of performative “eco” aesthetics. In the end, both poets insist that decolonial ecopoetics must associate language with tangible action, rather than remain confined to page or academy.

To deal with this dilemma, the poets do not simply resort to social media, a practice that could lapse into self‑promotion and/or performative activism, a self‑serving support to a cause. They also facilitate cultural projects through the creation of publishing houses, anthologies, artistic displays, workshops etc. In 2022, Evelyn Araluen called for national plans to advocate First Nations’ literature in a submission for the National Cultural Policy and mostly to officialize consultations with their communities in decision making and cultural projects developments. Indisputably, decolonial theories should benefit First Nations peoples under severe ecological pressure and help them prepare living sustainably in a world where they do not simply survive but thrive on their lands. Decolonial ecology should not remain at the symbolic level, where metaphors may also serve settler discourse. Such metaphorical engagements often leave intact the foundations of the colonial oikos. By contrast, the poets discussed here resist the ontological frameworks of extractivism and ruthless capitalism imposed by the settler-colonial worldview. In this perspective, the decolonial inhabitation theorised by Malcom Ferdinand does not simply oppose the colonial oikos; it constitutes a radical reconfiguration of Western conceptions of place, environment, and knowledge. Rather than a binary inversion, it demands a transformation of the very foundations of Western epistemology and political economy and calls for an end to the paradigm of extraction, accumulation and growth that sustained imperial domination and environmental degradation.

In Rewriting the Mainstream, Nyoongar elder Rosemary van den Berg advised academics to be humble and listen to Indigenous people more: “Academics who work in the field of literature should consult Aboriginal sources and read Aboriginal texts; and listen to the people” (van den Berg 120). This text, which was published in 1995 still resonates today, all the more as the Voice proposal was rejected in October 2023.10 Victims of setter-colonial power are best placed to articulate and manage their current living conditions, past experiences, and paths to achieve emancipatory aspirations: self‑representation by First Nations authors and community participation could more effectively address ongoing violence which affects both the land and its inhabitants (including non‑human entities).

Writing in a land up in flames has convinced both leading and emerging authors that they now urgently have to unsettle ideological and material manifestations of colonialism by combining words and actions. Poetic resurgence, as seen in these authors’ works, delineates possible futures in which First Nations’ knowledge is acknowledged not as peripheral but as central to rethinking ecological and cultural futures (without idealizing or instrumentalizing these poetic acts). It is a poetic and political gesture that supports ongoing forms of activism and deepens First Nations’ expressions of relationality with land as a continuation of enduring knowledges and practices for inhabiting the Earth in respectful and sustainable ways.

As Alison Whittaker noted in the foreword to the 2020 poetry anthology Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, “First Nations Writing Is on Fire!”, Jazz Money, Evelyn Araluen, and Ellen van Neerven develop poetic practices that articulate ecopolitical resistance within First Nations’ ontologies. Their poetry performs a form of cultural and territorial resurgence by reactivating ancestral narratives, oral traditions, and land‑based knowledge systems. Far from offering a reconciliatory discourse or symbolic activism, their work engages with poetry as a space of intervention, where language becomes a vector of presence, responsibility, and refusal. Through innovative formal choices and multilingual strategies, they reassert Country as a site of meaning, memory, and sovereignty. In doing so, they contribute to a broader praxis of decolonial inhabitation that resists settler-colonial structures and sustains relational bonds with land, beyond metaphor.