My thanks go to Giulia Loi for translating this article from its original French version, to Derek Woods and Liliane Campos for inviting me to think in terms of scale, and to Katherine Hayles for inspiring this work on Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future.

In the opening of his book Facing Gaia (2017), Bruno Latour explains what he means by the “New Climate Regime” (an expression he derives from the work of Aykut and Dahan 2015), noting from the outset that because of it, “everything changes in the way stories are told”:

I use this term [New Climate Regime] to summarize the present situation, in which the physical framework that the Moderns had taken for granted, the ground on which their history had always been played out, has become unstable. As if the décor had gotten up on stage to share the drama with the actors. From this moment on, everything changes in the way stories are told, so much so that the political order now includes everything that previously belonged to nature […]. (3)

At stake here is the status of nature, of the “physical framework”—essential, but conceived as inanimate—of modern scientific and political culture, but also of modern artistic and literary culture, which crucially includes what has been called “realism”. In literature and the arts, realism has indeed constituted a dominant mode of representation and narrative, from the nineteenth century onward. It has accompanied the coming to maturity of a certain industrial and positivist modernity, in Europe and North America. Even today, realism remains the norm in “serious” literature (no longer in its narrow definition, which would restrict it to the historical moment of Balzac and Hardy, but more broadly understood as the Other of the mythic, epic, fantasy or science fiction modes). A glance at the list of 2020 nominees for the Goncourt, Booker and Pulitzer prizes is enough to convince us of this (the cries of astonishment uttered that year, when L’Anomalie won the 2020 Goncourt—a science fiction novel! published by Gallimard!—show the persistent relevance of this norm, at least in the French-speaking world). But if the great “actors”—the politicians, entrepreneurs, and scientists that have been playing out the drama of modernity—suddenly see their “stage” coming to life, if Gaia becomes an agent of this drama, everything indeed changes in the way we tell stories. For it is then necessary to take a new category of characters seriously: climatic and geophysical planetary forces. Admittedly, those have never been totally absent from the novelistic scene—as the recent collection Le temps qu’il fait (Naugrette and Lanone 2020) demonstrates, tracing the role of weather in English literature from Chaucer to Dickens. But climatic and geophysical actors have, most of the time, been turned into mere décor by a literary modernity that has deployed most of its narratives on the scales of individual inner life, of family or community relations, or, to a lesser extent, of the city, region or nation.

In this article, I will try to elucidate how The Ministry for the Future (2020), the most recent novel by American science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, responds to the demands formulated by the new climate regime: how to tell stories in which geophysical entities act on a planetary scale? What techniques can a novel use to “face Gaia”?

Realists for a larger reality

To begin answering these questions, I would like to return briefly to that of realism. In 2014, receiving the lifetime achievement award from the American National Book Foundation, Ursula K. Le Guin gave a committed speech—abundantly cited since then, notably by Isabelle Stengers in her essay “Thinking in SF Mode” (2021), some of whose arguments I will take up here. Le Guin then declared, about this prize:

And I rejoice in accepting it for, and sharing it with, all the writers who’ve been excluded from literature for so long—my fellow authors of fantasy and science fiction, writers of the imagination, who for fifty years have watched the beautiful rewards go to the so-called realists.

Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom—poets, visionaries—realists of a larger reality. (113, emphasis mine)

Robinson appears as one of those “realists of a larger reality”. Instead of striving to represent “reality” as a given state of affairs, his fictions illuminate how it is perpetually produced by negotiations and experimentations, in workshops and laboratories, parliaments and schools, streets and fields, or on social networks. Thus refusing the description of a reality that would have been established once and for all, Robinson summons the natural and social sciences, with the debates and controversies animating them, to imagine this “larger reality” of which Le Guin speaks.

Before going further, however, I would like to maybe state the obvious in noting that traditional literary realism, when invested in social critique, can also participate in the production of a “larger reality”. This is explicit when we read in full Stendhal’s famous formula—often used as slogan for realism—describing the novel as “a mirror carried along a high road”. The narrator of The Red and the Black (1830) then continues: “His mirror shows the [muddy] mire, and you accuse the mirror! Rather accuse the main road where the mud is, or rather the inspector of roads who allows the water to accumulate and the mud to form” (chapter XLIX). Stendhal’s realism might not be especially well equipped to “see alternatives to how we live now”, but it can prepare the ground for such visions by showing how the present is produced (here by the inspector’s socio-technical agency). Realist critique may thus constitute a first step toward the speculative imagining of “other ways of being”. But what kind of mirror does it need to envision those hyperobjects (Morton) that are climate change, the sixth extinction, or the Anthropocene or Chtulucene (Haraway)? When the “ground” of the high road comes alive under our feet, and the “muddy mire” takes on a planetary scale, narratives have to embrace new scales, and widen their scope beyond individual, family and regional histories.

The Ministry for the Future attempts such upscaling, telling a story of the Earth from 2025 to about 2055; from the creation of a UN agency charged with defending the rights of future generations—dubbed the “Ministry for the Future” (16)—to the celebration of “Gaia Day” (545), which marks a relative restoration of our planet’s climatic and ecosystemic balance. Robinson thus works to remedy what Timothy Clark calls, following Hannes Bergthaller, the failure of the imagination in the face of the ecological crisis (Clark 2015, 18). Locating himself in the moralistic vein of the Stendhalian narrator, he claims to have written a “low bar utopia”:

And I write as a utopian science fiction writer, which at the moment we’re at right now in world history means that I have to set a pretty low bar for utopia. If we dodge a mass extinction event in this century, that’s utopian writing. (McKibbens 2021, unpaginated)

Indeed, the utopian breath carrying The Ministry for the Future does not push it away from realism, but on the contrary towards an archipelago of actual scientific works and technical experiments within political economy, finance, cognitive psychology, glaciology and ecology. While mobilizing those fields, Robinson’s science fiction fully plays the role that Isabelle Stengers attributes to the genre, that of keeping open the doors of the imagination, a “keeping open [that] does not involve the passivity of leaving open” (2021, 124). This writerly practice of speculation allows us to “resist the temptation to subscribe to the reasons we might give for accepting the order of things and maintaining that it could not be otherwise” (124, see also the notion of “otherwise” developed by Crawley 2016). “Thinking in SF mode”, as Stengers puts it following Haraway, is to recognize “SF” as a way of going beyond a literary realism limited to the description of reality as it has been so far: “So Far is the very cry of resistance against the normality claimed by states of affairs” (126).

When composing The Ministry for the Future, Robinson had to resist the hegemonic “normality claimed by states of affairs”: “Another thing that kept coming back to me when I was writing the book was how these ideas sound utopian crazy. We have that hegemonic response in our heads—an imitation of common sense—that says, ‘Well, that couldn’t happen’” (Gordon 2020, unpaginated). Refusing this “imitation of common sense”, Robison’s novel sharply contrasts with the resignation running through the dystopias (Moylan 2020, 164), post‑apocalyptic fictions and other eschatologies and collapsologies that have swarmed since the beginning of the 21st century (here is a sample, in literature: Oryx and Crake, The Road, Station Eleven; in cinema: The Day After Tomorrow, Melancholia; in video games: The Last of Us).

Helping us to “imagine real grounds for hope”, The Ministry for the Future deploys its reasonable utopia on a planetary scale, and makes it possible to envision a globalization that would no longer be placed under the colonial/imperial sign of appropriation and extraction, of the conquest of territories and markets, but under that of a community of destiny uniting earthlings, whether they are human or non-human, biological or geophysical.

Polyphony

It has become commonplace, following Bakhtin’s essays on “Dostoyevsky’s Poetics” and “Discourse in the Novel”, to define the modern novel as constitutively (though not systematically) an assemblage of voices and points of view. Harmonious or contradictory, expressing themselves in direct discourse or through narration, these voices and points of view are weaved into a textual matrix that Bakhtin situates at the crossroads of linguistic and social dynamics (we should add: of ecological dynamics, since not only does the novel models aspects of life, but its very existence depends on solar energy flowing into paper making trees, and into the plants feeding the writers’ and readers’ metabolism). It is in Dostoevsky that Bakhtin first finds this dialogical polyphony, internal plurilingualism or heteroglossia, following Otto Kaus’s reading of the nineteenth century Russian novelist in the light of an emerging capitalist consciousness that “broke down the seclusion and inner ideological self-sufficiency of […] social spheres” (Bakhtin 1984, 19). Although Bakhtin is essentially interested in its “structural peculiarities”, he agrees that “[t]he polyphonic novel could indeed have been realized only in the capitalist era” (19–20), a view that partially anticipates Jacques Rancière’s identification of its affinity for democracy (2014, 34). In seems in any case probable that, despite the universality that its defenders have wanted to allocate it (see for example Léon Daudet’s 1922 eulogy for Proust), the modern novel belongs to a specific phase of our civilization: relatively democratic (as far as the internal politics of Western states are concerned) and capitalist, but also: nationalist, individualist and humanist (or rather: anthropocentric). However, and as we have seen above, the traditional scales of its narratives seem unsuited to the realistic description of a drama whose spatial, but also temporal scope exceeds that of individual human consciousness and experience. Can we adapt polyphony to the larger reality of the new climate regime? Is the democratic agora of the novel hospitable to collective, technical or non-human voices? What happens when we extend the polyphonic novel to the planetary scale? We will now explore these questions, keeping in mind Anna Tsing’s critique of scalar operations, which she associates with the modern episteme (2015, 38–39) and its “triumph of precision design, not just in computers [with their “effortless zoom”] but in business, development, the ‘conquest’ of nature, and, more generally, world making” (2012, 505). Tsing warns us that scalar logics can block “our ability to notice the heterogeneity of the world” (505) and we should accordingly remain attentive to what changes, when we attempt to scale the novel up to the Gaian level.

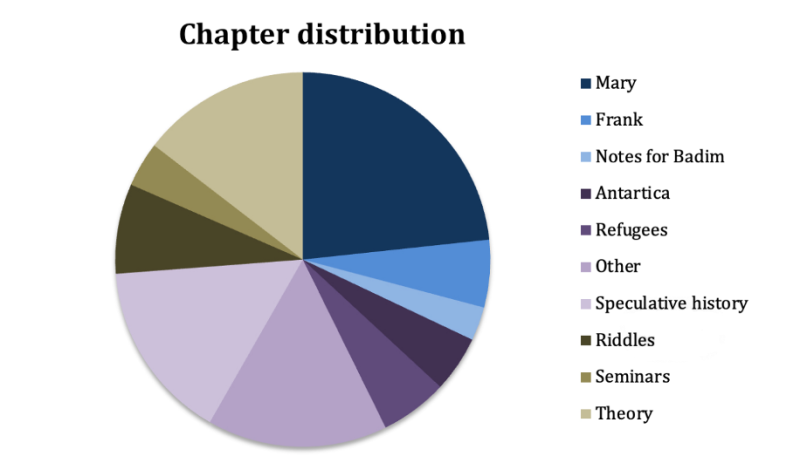

Planetary polyphony appears in any case as a strategy favored by Robinson’s novel to achieve a portrait (obviously partial) of the struggle against climate change in the central decades of the twenty‑first century. The Ministry for the Future is thus presented as a patchwork of voices and points of view, weaving together political and techno-scientific actors, identified protagonists and anonymous characters, individual and collective voices, human, animal and geophysical actants. These voices and points of view are arranged in 106 chapters, which we could classify into three main families:

-

the “classic” chapters, that follow Frank (a humanitarian doctor, traumatized by his experience of a heat wave that kills twenty million Indians in 2025, and who will become a sort of independent eco‑terrorist agent), Mary (the director of the “Ministry for the Future”), or the members of her team (these chapters are represented by the three blue areas on the following graph);

-

the chapters, of an equally narrative nature, but staging the voices of anonymous individuals, emblematic of a certain group (scientists in Antarctica, refugees in Switzerland, slaves freed from a ship or a mine), or the voices of a community, speaking in the first-person plural (eco‑terrorists, citizens of India, inhabitants of a flooded or dried‑up city), or a third‑person objective narration of events in Earth’s history (these chapters are in purple on the graph);

-

the non‑narrative chapters, that give voice to non-human entities (riddles formulated by the sun, the Earth, a photon, CO2, history, the market, herd animals, code), or that explain (directly, or through debates in the form of anonymous dialogues) different theories from the humanities and social sciences (Gross Domestic Product, ideology, cognitive or psychopathological errors in relation to the climate crisis, financial and banking history, the philosophy of technique; these are in brown on the graph).

The distribution of chapters on this graph clearly shows that those that focus on recurring and evolving characters (in blue), and that present a more familiar narratological profile, occupy only one‑third of the novel. Even among these, the three chapters classified as “Notes for Badim” present minutes of ministry meetings, written by an anonymous assistant, which essentially describe debates and decision-making around this or that measure supposed to fight climate change (carbon currency, quantitative easing, a new user‑owned social network…). The novel is thus largely dominated by collective and/or anonymous voices (in purple on the graph), and by non-narrative discourses of knowledge (in brown), leaving comparatively little room for the everyday life or heroic actions of individuals, for their emotions, ruminations and discussions, that have occupied a large part of the modern novel.

Collective voices

Through this assembly, we participate in a series of political, scientific and technical controversies, not in detail (they are too numerous), but through vignettes showing how they unfold over several decades. The reader thus follows experiments that fail or succeed, ideas that are put into action, a world being (re)constituted—on a relatively long time scale, albeit one that remains within the limits of a human life (and so one that does not extend into the geological, like for example in Gillian Clark’s “stone poems” studied by Sophie Laniel-Musitelli 2022). One of those experiments is the implementation of an international program to drain the watery carpet on which the glaciers of Antarctica slide towards the ocean, from its genesis during a simple discussion between glaciologists, at a conference (chapter 22), to a fairly advanced state of the project: “So, at the end of the season, we were flown into the middle of the Recovery Glacier, where we had drilled a double line of wells five years before. One of the lines was reporting that all its pumps had stopped” (472). This trivial-sounding passage interestingly departs from what we find in most realist fiction. Instead of focusing on individual and/or human affairs, it features a collective voice (“we”) responding to a technical actant (“one of the lines was reporting”), within a temporal framework defined both by natural cycles (“end of the season”) and by those of an engineering project (“five years before”). Its spatial framework is constituted by a geophysical entity (the “Recovery Glacier”), and its action is conditioned, not by biographical reference points, but by those of a collective enterprise that holds planetary stakes.

It should be noted in passing that the planetary “ground” or “décor” (to use Latour’s terms) is not particularly animated in these geoengineering Antarctic chapters, nor in the one describing the temperature-reducing program of spraying sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, devised by India after the catastrophic heat wave it endures (chapter 10). Robinson’s reasonable, polyphonic utopia thus includes terraforming endeavors that prolong the technicist hubris typical of industrial modernity (a hubris that becomes strangely recursive, contrasting with the modern view of progress as linear: “terraforming”—a term first used in science fiction to designate efforts to make a planet more Earth‑like—here implies we use all our scientific power to reshape the Earth in… its own form; a paradox unpacked by Woods 2020). These projects do not, however, impose on their executants an entirely dominant view of nature, since even the voice that passionately recounts glacier-breaking operations proposes to speak of “GEO‑BEGGING” rather than “geoengineering” (265). In the face of climate change, technical action is imagined as a supplication to the planet, and not the exercise of an instrumental will disconnected from Gaia.

The novel thus stages collective actions and voices, taking place on a planetary scale, but also on the smaller level of relations between cities/nations, for example when an individual speaks on behalf of Hong Kong: “What did we teach Beijing, you ask? We taught them a police state doesn’t work!” (513). As is often the case in The Ministry for the Future, the dialogic form here reflects a polyphonic controversy that, by being juxtaposed with the debates that animate technoscientific collectives, shows how reality is continuously produced, at the distinct but intertwined geophysical and political, planetary and international scales.

Speculative history

In addition to these collective or anonymous voices, the novel includes chapters of speculative world history under the new climate regime. Take, for example, this excerpt from chapter 51 (we are halfway through the novel):

The thirties were zombie years. Civilization had been killed but it kept walking the Earth, staggering toward some fate even worse than death.

Everyone felt it. The culture of the time was rife with fear and anger, denial and guilt, shame and regret, repression and the return of the repressed. They went through the motions, always in a state of suspended dread, always aware of their wounded status, wondering what massive stroke would fall next, and how they would manage to ignore that one too, when it was already such a huge effort to ignore the ones that had happened so far, a string of them going all the way back to 2020. […]

So it was not really a surprise when a day came that sixty passenger jets crashed in a matter of hours. All over the world, flights of all kinds, although when the analyses were done it became clear that a disproportionate number of these flights had been private or business jets […] But people, innocent people, flying for all kinds of reasons: all dead. […]

The War for the Earth is often said to have begun on Crash Day. And it was later that same year when container ships began to sink, almost always close to land. (227–229)

Here again, the temporal scale of events extends beyond that of everyday realism: the time unit is the decade (“the thirties”, “all the way back to 2020”). The spatial scale also goes beyond that of most modern novels, as the summary encompasses the whole planet (“the Earth”, “all over the world”). The subjects and objects of the action are collective, both human and technical (“civilization”, “everyone”, “the culture”, “they”, “sixty passenger jets”, “innocent people”, “container ships”). Considered from such distance, events appear caught in a complex mesh of causes and consequences that prevents straightforward moral judgement (that private jet owners are killed is “not really a surprise”, but they remain “innocent people”). Finally, the capitalization of two events (“War for the Earth”, “Crash Day”), historicizes them, implying a retrospective look at a planetary history that appears as already constituted—in contrast with the world-making negotiations and experimentations we follow in most of the novel.

This historicization is however itself destabilized by a historiographic discourse, formulated in one of the “theoretical” chapters. This one reveals the arbitrary and provisional, but also potentially subversive character of any periodization:

Of course attempts are always made to divide the past into periods. This is always an act of imagination, which fixes on matter geological (ice ages and extinction events, etc.), technological (the stone age, the bronze age, the agricultural revolution […]. They are dubiously illuminative, perhaps, but as someone once wrote, “we cannot not periodize” […]. Perhaps periodization makes it easier to remember that no matter how massively entrenched the order of things seems in your time, there is no chance at all that they are going to be the same as they are now after a century has passed, or even ten years. […] Raymond Williams called this cultural shaping a “structure of feeling”, and this is a very useful concept for trying to comprehend differences in cultures through time. (123–124)

Along with speculative history, the novel calls upon historiography to keep the doors of our imagination open, and to remind us that the order of things, the “normality claimed by states of affairs” (to reemploy Stengers’s formula), are always only temporary: historical periods follow one another, and worldviews with them. The Ministry for the Future thus train us once again to “think in SF mode”: by taking up the codes of academic writing (the reference Raymond Williams, a father of British cultural studies), it integrates science in fiction, in a speculation that puts “states of affairs” to the test of a dense, polyphonic world of intertwined agency. Collective voices, anonymous perspectives and scientific discourse are thus interwoven to make us experience a larger reality, that of a possible future for our planet. But Robinson also invites us to experience this future through the individual, embodied perspective of two protagonists: Mary and Frank.

Sensationalism

It is in Frank’s skin that we enter the novel, plunging in a terrible scene of eco‑horror (see Rust and Soles 2014 about this sub‑genre). An American humanitarian doctor, Frank is on a mission in Uttar Pradesh (a province in northern India, west of New Delhi), when a wet heat wave hits and kills, in three days, about twenty million humans. The horror of the situation, for the readers, lies in the feeling that such hecatomb is indeed possible. As climatologists Raymond, Matthews and Horton (2020) write, the occurrence of extreme wet heat has doubled on Earth since 1979; a worrying tendency, because the human body can no longer regulate its internal temperature when the outside temperature reaches 35° Celsius with 80% humidity (wet bulb temperature). This is what happens in The Ministry for the Future’s first chapter: as the local electrical network and the air conditioning fail, most of the city’s inhabitants find themselves “steamed” or, as in the case of Frank and of the citizens who take refuge in the lake, poached in hot water.

For ten intense pages, we share Frank’s point of view, or rather “point of feeling”, to borrow the more apt expression coined by neurologist Alain Berthoz (2004, 266). Indeed, the text foregrounds sensations of unbearable heat:

It was getting hotter.

Frank May got off his mat and padded over to look out the window. Umber stucco walls and tiles, the color of the local clay. […] Sky the color of the buildings, mixed with white where the sun would soon rise. Frank took a deep breath. It reminded him of the air in a sauna. This the coolest part of the day. In his entire life he had spent less than five minutes in saunas, he didn’t like the sensation. (1)

The initial sentence here functions as a potential synecdoche: designating the local weather, the first “It” can also refer to the planet—both are “getting hotter”. It loops the local and the global, a cross‑scale recursion that runs through and structures the entire novel. The text then takes us into Frank’s point of feeling, moving from a familiar action (easy to imagine with our muscular and motor body: “got off his mat and padded over to look”), to vision (the color palette: “Umber stucco walls”, “Sky the color of the buildings”), and then to respiration (“Frank took a deep breath”), which we are invited to experience through his memory of being in a sauna, a memory most readers can reactivate. This sensorimotor imagery, and the affects attached to it (“he didn’t like the sensation”) are vivified by the use of a minimalist free indirect style (“This the coolest part of the day”), aligning the reader’s inner voice with that of Frank, and thus facilitating the embodied sharing of his bodily state.

This initial situation deteriorates rapidly, and the following dawn reveals a macabre picture:

Four more people died that night. In the morning the sun again rose like the blazing furnace of heat that it was, blasting the rooftop and its sad cargo of wrapped bodies. Every rooftop and, looking down at the town, every sidewalk too was now a morgue. The town was a morgue, and it was as hot as ever, maybe hotter. The thermometer now said 42 degrees, humidity 60 percent. (8)

The passage from the figurative (“like the blazing furnace of heat”) to the literal (“that it was”) materializes a situation that should have remained imaginary (eco-horrific). Repetition and variation (“Every rooftop… every sidewalk too was now a morgue. The town was a morgue”) follow Frank’s progressive realization of the extent of the disaster. As in the previous sentence, this realization oscillates between the metaphorical and the literal: the town is both like a morgue, and truly a morgue. This difficulty in fixing reality also translates into a sensory uncertainty (“maybe hotter”), which the narrative, still in internal focus, tries to overcome by an objective measure (“42 degrees, humidity 60 percent”).

The chapter closes the following night, as Frank and other citizens have taken refuge in the lake, from which they cannot help but drink the corpse-infused hot water. By giving us, from the start, the embodied experience of this nightmarish climatic event, The Ministry for the Future forces us to share the trauma that will motivate the eco‑terrorist actions of survivors (like Frank, and the members of an organization called the “Children of Kali”), but also the unilateral diffusion, by the Indian government, of aerosols in the Earth’s atmosphere, to create a cooling comparable to the one caused by the explosion of the volcano Pinatubo. Exploiting the scale and terrain of individual feelings, this sensationalist episode makes tangible the intensity of the catastrophe, an intensity against which readers will measure the interventions of the novel’s various actors (activists, refugees, scientists, bankers; individuals, nations, chemical elements, technical devices…). These interventions, spread over some thirty years, will finally allow the climate to stabilize, and are described with great sobriety, if we compare with the opening scene (and this in spite of the dramatic nature of the events that will affect Frank, Mary and certain members of her team: assassination, cancer, divorce, terrorist bombings, a flight on foot across the Alps…).

We can consider this initial episode, filled with eco‑horrific energy and playing powerfully on the reader’s empathic and sensory‑motor imagination, as a seed‑situation, the core around which the world imagined by Robinson grows. As Isabelle Stengers writes about another science fiction writer:

Le Guin tells us that it is often the imagination of a situation that provides her with the starting point for a fiction, yet this situation must have the ability to call forth a world to which it would belong. This world is fictional but must have consistency: it must make its creation, and the exploration of what it demands, inseparable. (2021, 125).

In The Ministry for the Future, this consistency is in part produced by the heat wave scene, which calls forth the novel’s polyphony of human and non‑human, individual and systemic, organic and geophysical voices, each charged with its own interests. It is through this assembly of voices and points of feeling that the world of the novel manifests itself. Responding to the demands of the new climatic regime—demands made clear during the sensational, initial situation—this consistent, polyphonic world scales up to the planetary level. Zooming out, it shows how the fate of individuals is inextricably linked to that of the planet. It is because Frank suffers from climate trauma that he will briefly take Mary hostage, in the hope that she will take more radical action against climate change, which she will indeed do, authorizing clandestine sabotage operations to be led from within her own organization, and thus contributing in the long run to stabilize the climate. The traumatic seed-situation thus produces a narrative matrix, a world where collectives interact across (political, ecological…) scales, as Katherine Hayles (2021) underlined during a recent oral intervention.

Non-human actants

One of the consequences of scaling up the polyphonic novel to the planetary level, in The Ministry for the Future, is its inclusion of non-human voices. Robinson cleverly invokes these voices in a series of chapters in the form of riddles, posed in the first person. For example, the second chapter, which we approach still in shock from the heat wave scene, lets us guess that the voice we are hearing is the sun’s:

I am a god and I am not a god. Either way, you are my creatures. I keep you alive.

Inside I am hot beyond all telling, and yet my outside is even hotter.

At my touch you burn, though I spin outside the sky. As I breathe my big slow breaths, you freeze and burn, freeze and burn.

Someday I will eat you. For now, I feed you. Beware my regard. Never look at me. (13)

This cosmic “I”—by stating the titanic power of life and death it holds over us, and by voicing an imperative constitutive of the human condition (“Never look at me”)—makes visible the sun’s divine dimension. This dimension implies a subjection to nature that a certain Modernity, in its hubris, has tried to ignore. It is consequently unsurprising that the non-human here speaks in a format that recalls the medieval (hence pre‑modern) Anglo‑Saxon tradition of riddles. As is the case in Tolkien’s works (see Curry 1997)—another piece of speculative fiction that played a major role in the emergence of the late twentieth century ecological, posthumanist consciousness and culture—through these riddles, the medieval serves to remedy Modernity, providing a format through which the novel rehabilitates that “physical framework that the Moderns had taken for granted” (Latour). But if the sun is “a [pre‑modern] god”, it is also “not a god”: its divine qualities are articulated through its physical qualities, as defined by science (solar cycle, temperature, ecological role). Scientific knowledge thus feeds an eco‑religious, neo‑pagan respect for planetary, non‑human actants, a feeling that finds fertile ground in the heat wave trauma the reader has just experienced.

The possibility of a spiritual response to the new climate regime becomes explicit at the very end of the novel, during the simultaneous, planet wide celebration of “Gaia Day”, which gives us a glimpse of the tremendous joy and spiritual awakening accompanying humanity’s reconciliation with its environment. But the polyphonic novel remains a “reasonable utopia”, and Gaia Day is also the occasion of this exchange between Mary and her new friend Art:

Did you feel the moment?

No. It was too cold.

Me neither. But people seemed to like it. (546)

By zooming in on this sober reaction, weaved in with other voices (including the awe‑inspiring non‑human riddles), Robinson provides us with a variety of cognitive and affective tools to re-imagine our attachment to the Earth and to try to extend, to the planetary scale, the Heideggerian injunction of relearning to dwell, to “be of the land” (in “Building, Dwelling, Thinking”).

A reasonable utopia?

Among these various tools is the (parsimonious) use of lists, as in chapter 85, which enumerates, in alphabetical order (from Argentina to Zimbabwe), the associations participating in an international summit on climate change:

Hi, I am here to tell you about Argentina’s Shamballa Permaculture Project. We are representatives of Armenia’s ARK Armenia, happy to be here. Down in Australia we’ve connected up our Aboriginal Wetland Burning, Shoalwater Culture, Gawula, Greening Australia, How Aboriginals Made Australia, Kachana Land Restoration [… … …] I am from Zambia to tell you of the Betterworld Mine Regeneration. I am from Zimbabwe to speak for the Africa Centre for Holistic Management, and the Chikukwa Ecological Land Use Community Trust. (425–428)

Like the evocation of the heat wave, or of the “sun god”, this dense list, stretching over four pages, makes us feel almost physically the scope of the climate stakes. Utopian but reasonable, speculative but pragmatic, it carries the dream of a humanity capable of uniting in a single community of interest and destiny.

This utopian breath is central Robinson’s literary endeavor, helping us to “imagine real reasons to hope” (Le Guin), and to envision the new pleasures possibly offered by the ecological transition. The novel thus describes the replacement of airliners by airships, trains and boats, perhaps with a certain naivety (but isn’t that a judgement based on a deceptive common sense? On a false “normality claimed by states of affairs” (Stengers):

Mary took a train to Lisbon and got on one of these new ships. […] They sailed Southwest far enough to catch the trades south of the horse latitudes, and in that age‑old pattern came to the Americas by the way of the Antilles and then up the great chain of islands to Florida. The passage took eight days.

The whole experience struck Mary as marvelous. She had thought she would get seasick: she didn’t. She had a cabin of her own, tiny, shipshape, with a comfortable bed. Every morning she woke at dawn and got breakfast and coffee in the galley, then took her coffee out to a deck chair in the shade and worked on her screen. […] She stopped working for birds planning by, and dolphins leaping to keep up. (418)

Such “marvelous”, pastoral crossing sounds like a dream for many of us traveling for professional reasons: there are worst things than being “stuck” for eight days on a sailboat between Lisbon and the West Indies, drinking coffee on a deck chair in the shade, working while dolphins jump around the merry ship!

This scene participates in The Ministry for the Future’s reasonable utopia, drawing, through the ecological catastrophe, hope for new ways of life. The novel thus responds to the demands of the new climate regime. By scaling up its narrative to the planetary level, by integrating non‑human and collective voices in its polyphony, by canalizing the sensational energy of a situation to power up its fictional world and speculative history, and by caring for the politics and technics necessary to build a reality beyond what we have known so far, Robinson’s speculative fiction might just be an example of that realism of a larger reality that Ursula K. Le Guin deemed to be called for by the hard times that are coming.