Introduction

Soon after the result of the 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom’s continued membership of the EU, many journalists, and scholars, have started (or continued) to question some of the claims made during the campaign, in particular by the pro-Brexit side of the debate (Begg 2019; Mallaby 2019). What turned out to be, most of the time, “Brexit lies” (Grey 2022, 2023), along with Trump’s victory the same year, are symptomatic of what Fisher and Gaber (2022) call “strategic lying”, which seems to be part of the post-truth political era we currently live in (Marshall and Drieschova 2018; Allen and Stevens, 2018: 11; Musolff, 2022: 122). “Strategic lying” is defined by both “its misleading content and its strategic use within the context of a political campaign in which parties battle to control the campaign agenda” (Marshall and Drieschova 2018). It helps frame certain issues by giving prominence to a particular – and deceitful – understanding of political narratives.

As a matter of fact, storytelling, of which political narratives are the “communicative product” (Reisigl 2021), played an important role during the Brexit campaign and so-called “Brexit narratives” (Ridge-Newman et al. 2018) were instrumental in the overall framing of the Brexit debate (Bonnet 2020). This is why abundant literature has been devoted to the “populist narratives” (Brusenbauch Meislová 2021), elaborated by the Leave campaign, and based, in part, on the claims/lies that leaving the EU would bring an extra £350M to finance the National Health Service (NHS) (Schnapper and Avril 2019: 50), or that non-EU countries would line up to strike new free-trade deals with the United Kingdom (UK) (Clarke et al. 2017). It seems however that little attention has been devoted to the fallacious argument/ narrative that the EU was secretly plotting to ensure that Turkey would soon join the European organisation, and how leading Brexiteers narrated this idea for political gain, in what we might call “the Turkey story”.

In line with the general theme of this special issue of ELAD-SILDA, the aim of this paper is therefore to determine whether Vote Leave’s narrative about Turkey being “in the pipeline” to enter the European Union (EU) amounts to a conspiracy theory, or whether it might be considered as mere disinformation – or “strategic lying” – to fuel resentment at the EU, by dwelling on “ethnocentric sentiments” (Sobolewska and Ford 2020: 228) and resorting to what Wodak calls “the politics of fear”, through the discursive construction of “scapegoats and enemies” (2021: 8). Turkey’s accession to the EU has indeed led to highly sensitive political debate within the European organisation (Aydin-Düzgit 2012).

To examine how the argument about Turkey was narrated in discourse, we have assembled a corpus of documents from Vote Leave’s official website. The theoretical, contextual and methodological framework, defined in the first part, will help us understand the results of the narrative analysis, in the second part. The conclusion will discuss the conspiratorial potential of the “Turkey story” and introduce the concept of “strategic conspiracy”.

1. Contextual approach, theoretical framework and methodology

1.1. Setting the scene: Brexit as fertile ground for the emergence of the “Turkey story”

In a bid to mend political and ideological divisions within his party and reinforce his leadership – by neutralising the UK Independence Party (UKIP) threat and settling the European question for a generation – David Cameron proposed, in January 2013, a referendum on the UK’s continued membership of the EU (Dorey 2021). After negotiating a new deal with the EU, albeit quite limited, he led the Remain campaign. “Stronger in Europe”, the official group to stay in the EU, faced a fragmented, yet extremely determined, well-funded and highly organised opposition. Two groups, with different agendas, at first, campaigned to leave the EU: one unofficial organisation, Leave.EU, close to UKIP (Browning 2019), and Vote Leave, more “respectable” (Clarke et al., 2017: 31) and close to the Conservative Party, which was designated as the official Leave campaign by the Electoral Commission (Schnapper and Avril 2019).

The issue of sovereignty was at the heart of both Leave groups. Vote Leave focused on economic sovereignty and Leave.EU decided to lay the emphasis on territorial and cultural sovereignty (Browning 2019). The “heart vs. head” narrative dominated the campaign, as the crux of the debate was to win over wavering voters, who resented the EU but who thought that leaving might be too risky (Clarke et al. 2017: 33). As the economic arguments were clearly in favour of the Remain campaign, Vote Leave decided to change its strategy and to “turn up the volume on the one issue that was dominating the minds of most voters”: immigration (Clarke et al. 2017: 53). The overall narrative now was that uncontrolled EU immigration was putting immense pressure on the ailing UK social services, such as the NHS and the school system. Resorting to container metaphors, Vote Leave members depicted Britain as overwhelmed by immigrants and on the brink of collapse (Bonnet 2020). One month before the referendum (Worral 2019), Vote Leave senior member Michael Gove warned that Turkey and four other countries could join the EU as soon as 2020.

The “Turkey story”, as we have decided to call it in this paper, was simple: along with other Eastern – and predominantly Muslim – countries, Turkey was “in the pipeline” to enter the European Union and both the EU and the UK government were paying huge amount of money to facilitate the process. In addition to the claim that 15 million Turks would settle in the EU in the first ten years of membership, Turkey’s entry would stretch the EU borders all the way to “dangerous” countries, such as Syria, Iraq and Iran. Ker-Lindsay (2018) argues that the significance of this story should not be downplayed:

Ultimately, the claim that Turkey was on course to join the European Union, and that this would lead to an almost immediate surge of immigrants into Europe, and thus the United Kingdom, seems almost certain to have shaped the views of a significant number of voters. Whether this was merely an additional reason to leave – or was the issue that swung it – is hard to say. However, given the significance or the immigration debate and Turkey’s central role in that discussion, and given how close the final result was, there is a good case to be made that the unfounded claims made by the Leave campaign about Turkish membership of the EU have ultimately cost Britain its own membership of the Union.

The emphasis laid on Turkey is, arguably, not random. Aydin-Düzgit (2012: 1) explains that the country’s potential entry “poses a profound challenge to the European project due to the perceived ambiguities over its ‘Europeanness’”. Amid highly emotional – and sometimes heated – debates, many EU politicians have argued that “Turkey’s democracy, geography, history, culture and the mindset of its politicians as well as its people qualify it as a non-European state that is unfit to become a member of the EU” (ibid.). Turkey, as a predominantly Muslim country that is geographically straddling Europe and Asia Minor, raises ontological fears and cultural anxieties which were duly exploited by politicians, in order to use the “Turkish Other” as “a mirror for defining not only the ‘European Self’, but also European values” (Tekin 2010). In reality, the pace of Turkey’s potential accession has significantly slowed down in the past decade, in part because of Turkey’s authoritarian turn (Ker-Lindsay 2018), which means that VL members’ assertion that the country was about to enter the EU was not vindicated by political facts (Marshall and Drieschova 2018: 94).

The impact of this story, however, and its unfounded dimension, highlights the conspiratorial potential of the Brexit debate. As a matter of fact, belief in conspiracy theories tend to increase during political campaigns (Golec de Zavala and Federico 2018) and the Brexit referendum campaign was indeed no exception (Payne 2016). As such, the inherent link between Brexit and conspiracy theories has been the subject of much academic research. Digital media in particular played a key role in the dissemination of conspiracy thinking (Del Vicario et al. 2017) about how the Remain side tried to undermine the Leave campaign by manipulating the mainstream media or by “voluntarily” crashing the government’s voter registration website (Bienkov 2016). Douglas and Sutton (2018) argue that conspiracy theories tend to change people’s attitude on important political matters, this is why much attention has been paid to the influence of such conspiracy theories on people’s voting in the referendum (Jolley et al. 2021). As “alternative narratives” (Douglas and Sutton 2018), conspiracy theories are both subversive and empowering, and in this article, we propose to study them as discursive constructions (Catenaccio 2022). This approach, nonetheless, calls for terminological clarification.

1.2. Conspiracy theories as narrated explanations

As “feature of civilised social life” (Douglas and Sutton 2018), conspiracy theories are a constant of human societies (Demata et al. 2022: 1). The creation of the term “conspiracy theory”, on the other hand, is fairly recent and is usually attributed to Austrian philosopher Karl Popper, who talked about so-called “conspiracy theory of society” in his 1952 book The Open Society and Its Enemies (Diéguez and Delouvée, 2021: 96). At its most basic, conspiracy theories are “attempts to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events as secret plots by powerful and malicious groups” (Douglas, Sutton and Cichocka, 2017). They usually emerge in times of crises (Desormeaux and Grondeux 2017). This is why the European Commission, along with the UNESCO, have recently issued “educational infographics” to debunk the recent spread of Covid-19 pandemic-related conspiracy theories. In a similar vein, the EU-funded research program Compact (Comparative Analysis of Conspiracy Theories) has issued a “Guide to Conspiracy Theories” to provides an overview of the phenomenon of conspiracy theories and recommendations on how to deal with them.

The term “conspiracy theory” remains nonetheless ambiguous as no consensus seems to have been reached to propose an accepted, and definitive, definition. In what might amount to an academic continuum, Dieguez and Delouvée (2021: 66-67) argue that some researchers adopt a neutral approach and see conspiracy theories as an explanation for a historical event which happens to involves a conspiracy. Others consider conspiracy theories as alternative explanations. As it comes in addition to the official version, it is, by definition, false and unreliable, if not preposterous. However, most researchers today tend not to discard conspiracy theories as totally irrational (Giry 2017). Growing attention is devoted today to so-called “conspiratorial studies”, which, according to Forberg (2023) “aims to treat conspiracy theorists not as engaged in irrational, anti-political responses but as ‘a rational attempt to understand social reality’ by ‘more or less normal people’”. As a matter of fact, many scholars acknowledge that “conspiracy theories can be a way of expressing opposition, or can be part of what creates a sense of group identity” (Compact 2020: 9), which makes conspiracy theories particularly relevant as far as Brexit is concerned because, as Sobolewska and Ford (2020: 234) argue, Brexit is the political expression of “new identity divides over immigration, national identities and equal opportunities”. Conspiracy theories therefore help create antagonism between different social groups, which vindicates our focus on the “Turkey story”, as “belief in conspiracy theories constitutes a ‘mentality’ based on individuals’ and groups’ fears and antipathy against minorities and outgroups” (Moscovici 1987).

As stated before, conspiracy theories represent an alternative story, supposedly coming from regular people. Demata et al. (2022: 1) argue that “conspiracy theories attempt to make sense of the world by constructing narratives running directly counter to the ‘official’ ones, often by ‘connecting the dots’ between otherwise seemingly unrelated events that, for them, are evidence of a conspiracy”. As narratives, they play with reality, or at least overlook concrete – and contradictory – elements that seem not to fit with the overall narrative structure (Uscinski 2020). We might therefore argue that most of the power of attraction of conspiracy theories, and their reassuring dimension, resides in their narrative forms. The emotions they create are in opposition to the rationality of both the official version and the complexity of the world. Indeed, as stated in the Compact guide (2020: 4), conspiracy theories “do not spring from nowhere […] often, they are responses – albeit simplified and distorted – to genuine problems and anxieties in society”.

The narrative format of conspiracy theories is universally recognized in the academic literature and yet very little research has been conducted on conspiracy narratives per se (Mason 2022: 171). This academic void has been partly filled by Demata et al.’s recent book (2022) on conspiracy theory discourse. Our research intends to draw on this work, by proposing a narrative analysis of the “Turkey story”.

1.3. Stories, narratives and the persuasive dimension of storytelling in political communication

Narratologists tend to differentiate stories and narratives (De Fina 2017: 234). Abbott (2008: 21) explains that “a story is the series of events at issue, while narrative is the story “mediated” through how the teller presents it”. Generally speaking, “story” can be defined as “a sequence of events, experiences, or actions with a plot that ties together different parts into a meaningful whole” (Feldman et al. 2004: 148). It is a series of “temporally and causally ordered events”. A narrative, on the other hand, is “one verbal technique for recapitulating past experience” (Labov and Waletzky 1967: 13) which constitutes a cognitive activity (De Fina and Georgakopoulou, 2012: 5) that is inherently subjective and has an emotional (Reisigl 2021) and persuasive (Polletta 2006) effect on the story recipient. In political communication, we envisage the concept of story as “the use of an amusing, or otherwise emotion-generating anecdote to make a point, break the ice, or in some other way support an effective public utterance” (Schnur Neile 2015: 1). As such, our understanding of story in political discourse is “a spreading story aimed to explain an aspect of reality or to interpret events, and it is able to influence the opinion and behaviour of people” (Casagrande and Dallago 2023: 125).

Stories, and the way they are narrated, play a key role in political communication (Gabriel 2015: 276; De Fina 2017). Narratives are often favoured in political discourse today because they are “seen as representing a non-argumentative, more common-sense and therefore more grass-roots inspired mode of conveying political views” (De Fina 2017: 239). Atkins and Finlayson (2012) explain that, over the past 40 years or so, narratives, which are “the communicative products of the process of storytelling” (Reisigl 2021), have become ubiquitous in political rhetoric (De Fina, 2017: 236). Storytelling is a “polymorphous concept” and “a relatively old marketing technique, whose aim is to use narration to arouse interest by telling stories to audiences” (Gallot and Leroux, 2021: 3). Political storytelling is sometimes considered as deceitful and dangerous propaganda, because it operates, supposedly, without the knowledge of the recipient (Salmon 2007). This negative – and restrictive – understanding has been criticized and researchers nowadays call for a more neutral approach, so as to better appreciate all the facets of this polymorphous discursive tool. Storytelling plays indeed a key role in political communication because it reinforces the mobilisation of people around certain values (Berut 2010) and contributes to the construction of a “ritualization” (Dayan 2006: 166), i.e., a worldview that is specific to a given society. The narrative format is indeed particularly valuable in political communication, as Feldman et al. (2004: 148) explain: “through the events the narrative includes, excludes, and emphasizes, the storyteller not only illustrates his or her version of the action but also provides an interpretation or evaluative commentary on the subject”.

Storytelling seems to be one of the fundamental characteristics of the human species, because, as Fludernik (2009: 1) argues: “the human brain is constructed in such a way that it captures many complex relationships in the form of narrative structures, metaphors or analogies”. Communicating narratives allow us to mobilise our senses and share our emotions, which is crucial to the process of social interaction. Fisher (1985: 74), who developed the “narrative paradigm” theory, even talks of “Homo Narrans” – the idea that “humans are storytellers” – and argues that meaningful communication is in the form of storytelling. Stories therefore have a foundational dimension (Barthes 1966: 1).

What makes narratives appealing, in terms of political persuasion – and conspiratorial thinking – is their structural and conceptual power. White (1980: 5) considers narrative as a “metacode” that can be understood as the solution to the problem of “fashioning human experience into a form assimilable to structures of meaning”. Stories simplify complex issues by ordering the chaos of the world through the introduction of a familiar narrative pattern: a beginning, a middle, and an end that contains a conclusion or some experience of the storyteller (Titscher et al. 2000: 125). As such, stories bring (superficial) cohesion and meaning to what could sometimes be seen as a (naturally) chaotic – and ruthless – world. Besides, shared narratives enable us to create the ties that form a sense of belonging and identity within a community.

Narratologists have long recognized the cognitive dimension of narratives (Prince 1982; De Fina et Georgakopoulou 2012; De Fina and Georgakopoulou 2015). Labov (1972) explains that narrative is nothing but “the cognitive representation of reality” imposed by narrative structure on our experience of the world. Brooks (2001) even argue that narratives constitute “a universal cognitive tool kit” to make sense of the world and to construct our sense of self. Narratives appeal to powerful emotions which constitute “potent, pervasive, predictable […] drivers of decision making” (Lerner et al. 2015 1). Drawing on Lakoff’s conceptual approach, Seargeant (2020: 63) argues that stories function as “an organizing framework for our thoughts”, notably in political persuasion:

Through careful management of language, those in power can influence the way our brains interpret important political issues and thus influence the way we perceive reality […] the associations that build up around a concept, that become the ‘natural’ way of thinking about that idea, are often structured by an underlying story (2020: 141).

Polletta (2015: 37) identifies two main cognitive drivers to explain the ubiquity of storytelling in political communication. First, the so-called “willing suspension of disbelief” entailed by the narrative structure tends to inhibit counterarguing, simply because when people use narratives rather than arguments as a means of persuasion, the audience is less concerned about the credibility of the speaker (Green and Brock 2000, cited in Seargeant 2020: 78). Second, she argues that people tend to naturally “adopt the views of the character with whom they identify” which encourages to “vicariously [share] the emotions and perspectives of the character” (Polletta, 2015: 38). Fludernik (2009: 6) explains that “the experience of these protagonists that narratives focus on, allows readers to immerse themselves in a different world and in the life of the protagonists”.

In a similar vein, by relating stories, a politician effectively acquires the status of storyteller, that is, the person who makes stories possible, and by extension, the person who is able to set things in motion. Storytellers are therefore in a position of control and authority. Anthropologists have showed the social and societal importance of stories, as storytellers tend to coordinate social behaviour and encourage cooperation (Smith et al. 2017). This is why storytellers are often associated with the notion of wisdom: they are in possession of a certain knowledge, and more importantly, they are able to share and pass on this knowledge to others, by making complex situations or events more intelligible. Storytelling is therefore a powerful tool which helps build the ethos of a politician and reinforces their position of power and their leadership over a given community.

1.4. Corpus and methodology: The moral economy of critical narrative analysis

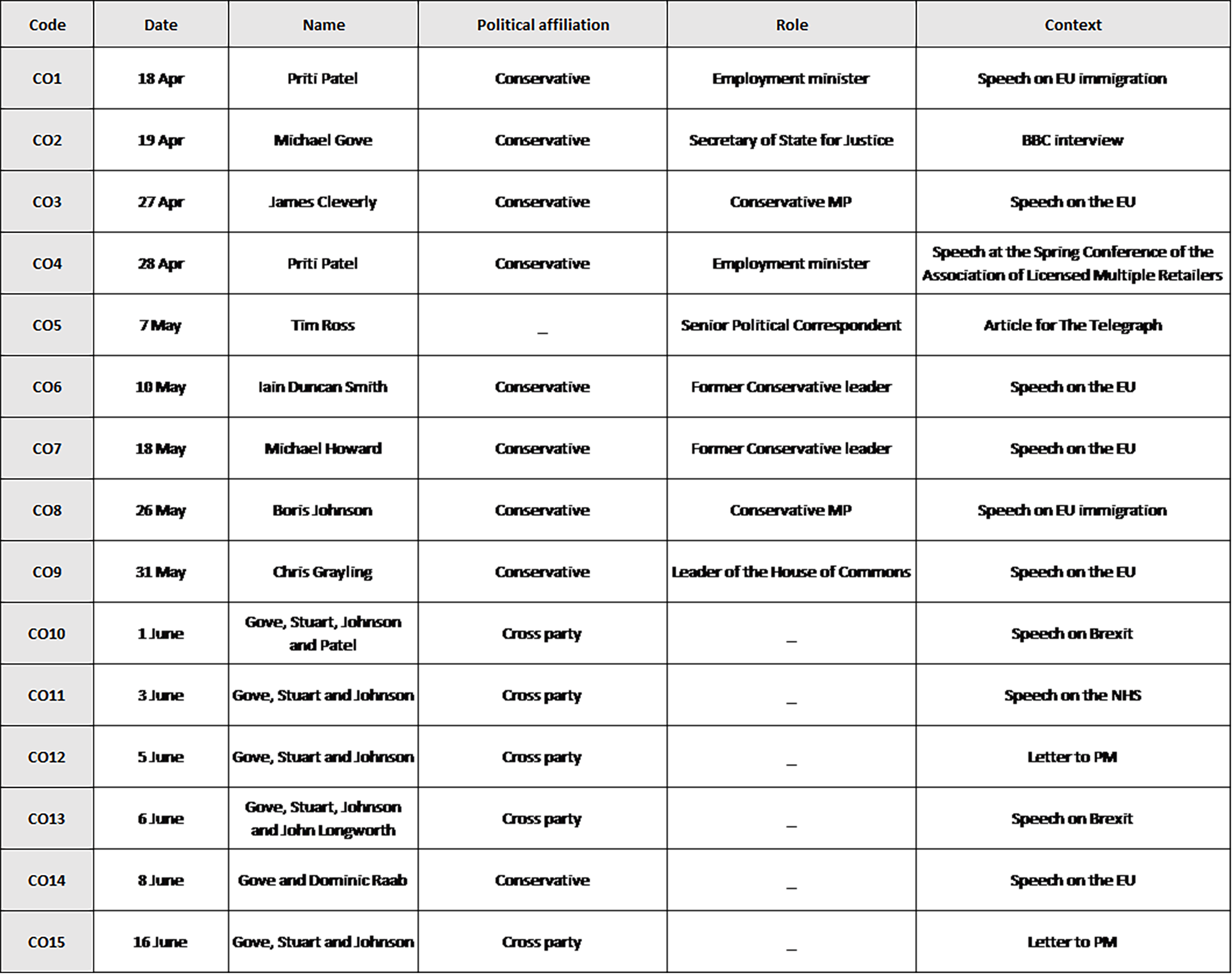

To investigate Vote Leave’s rhetoric and in order to carry out a comprehensive narrative analysis of the “Turkey story”, we uploaded all the documents available on VL’s official website in the “Key speeches, interviews, and op-eds” section onto corpus manager and text analysis software Sketch Engine. From this initial set of documents (statements, speeches, open letters and newspaper articles, 53,389 words in total), we extracted every occurrence of the terms “Turkey” and “Turkish” which allowed us to trim down our corpus to 15 texts (Table 1 in Appendix).

Vote Leave was a cross-party organisation, with both Labour and Conservative MPs, however, the extraction process shows that the terms “Turkey” and “Turkish”, and by extension the “Turkey story”, were overwhelmingly present in documents produced by or about Conservative politicians. The only Labour MP in the corpus, Gisela Stuart, is always writing with Conservative politicians (CO10, CO11, CO12, CO13 and CO15) and the only document not produced by a politician (CO5) is an opinion piece on Tory MPs, in a conservative-leaning newspaper. This restrictive use, we argue, calls for a critical approach. Van Dijk (2001: 352) describes Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as “a type of discourse analytical research that primarily studies the way social power abuse, dominance, and inequality are enacted, reproduced, and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context”. Wodak (2011: 38) understands CDA as “a problem-oriented interdisciplinary research programme” which effectively subsumes “a variety of approaches, each with different theoretical models, research methods and agenda […] what unites them is a shared interest in the semiotic dimensions of power, identity politics and political-economic or cultural change in society”.

CDA linguists are mainly concerned with two interrelated concepts, context and persuasion, and believe that language is crucial “in determining social power relationships” (Charteris-Black 2014: 83). The aim of CDA, therefore, is to bring to light the manipulative use of language by people in position of power and to show how “difference in power and knowledge are created by inequalities in access to linguistic resources” (83). Hence the importance of power, as Charteris-Black (84) argues:

Power is a central notion in CDA and can be taken to mean the way that a particular social group is able to enforce its will over other social groups. Power is when a powerful social group (A) persuades another social group (B) to do things that are in A’s best interests, and prevents B from doing things that are B’s best interests.

As such, CDA enables to decode the political ideology – and personal ambitions – behind the rhetoric used by politicians, as Waugh et al. (2016: 72) explain:

By studying discourse, [CDA] emphasizes the way in which language is implicated in issues such as power and ideology that determine how language is used, what effect it has, and how it reflects, serves, and furthers the interests, positions, perspectives, and values of, those who are in power.

We argue that CDA is probably the most appropriate theoretical approach for our study, for two main reasons. First, because VL was the official campaign to leave the EU, which provided it with important public resources and significant media exposure. Zappettini (2019: 404) argues that Vote Leave “had the power to influence public opinion on the meaning of Brexit and to frame the context of the debate by reproducing, challenging or silencing certain discourses and ideologies”. As such, the Out group was able to control the narrative, which is a prerequisite to the process of political persuasion but also calls for critical deciphering.

The second element of interest, as noticed before, is that our corpus is composed only of documents produced by or evoking Tory politicians, most of whom Conservative heavyweights, such as Boris Johnson or Michael Gove. VL, hence, represented the “respectable” side (Clarke et al. 2017, 31) of the leave campaign, which means that a potential conspiratorial, even xenophobic narrative about Turkey, seems to run counter to the social liberal values that incumbent Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron had tried to promote when he set to “decontaminate” his party’s brand in 2005 (Bale 2010: 285). CDA will therefore enable us to decipher how leading Conservative members of VL used their supposed respectability to convey a conspiracy-inspired message.

Since our intention to focus on the “Turkey story”, we will combine CDA with narrative analysis, what Souto-Manning (2014: 163) calls “Critical Narrative Analysis” (CNA) and which, she explains, “allows us to learn how people create their selves in constant social interactions at both personal and institutional levels, and how institutional discourses influence and are influenced by personal everyday narratives”.

Charteris-Black (2014) argues that CDA must follow a three-stage methodological process. The first stage consists in analysing and explaining the overall context, or “speech circumstances”. The second stage involves both the identification of storytelling units and their eventual classification according to their inherent meaning, and function within the text. To this end, the theoretical framework of our research is based on Soteras’ work. Drawing on Taguieff’s ground-breaking analysis of conspiracy theories, she proposes three “key pillars” (2020: 74) that seem to underpin and structure every single example of conspiracy theory. This typology will constitute the backbone of our analysis:

- The first pillar argues that a group of conspirators secretly act behind closed doors, for their own vested interest. Conspiracy theorists believe that there is “a secret, omnipotent individual or group that covertly orchestrates the events of the world” (Fenster 2008: 1). The key question is “cui bono” or “who profits from this?”. The emphasis on secrecy and the inherent link with powerful – and malevolent – actors are at the core of every definition of conspiracy theories. In terms of narrative structure, those conspirators are “villains” to be defeated whereas conspiracy theorists become whistle blowers and selfless “heroes”.

- The second pillar highlights the idea that nothing is as it appears and people are being lied to. The aim of conspiracy theorists therefore is to “connect the dots” so as to correct the official version and unveil the truth by revealing the identity of the culprits. This detective work aims to propose an alternative narrative to the one put forwards by official sources. As such, conspiracy theorists are inherently anti-establishment, which aligns them, ideologically, with populism in their rejection of the elite and their defence of regular people (Demata et al., 2022: 4). Many scholars recognize that conspiracy theories and populism “share the same basic tenets” (ibid.: 4) and that populist leaders often construct conspiracy theories to create “a strategically ‘useful’ scapegoat” (Wodak 2021: 84).

- The last pillar claims that everything is connected, nothing happens by accident, there are no coincidences. In that way, conspiracy theories have a reassuring dimension in that as they “make the world meaningful because they exclude chaos and coincidence […] they also make the world intelligible because they provide a simplistic explanation for political and social developments […] they are a strategy for dealing with uncertainty and resolving ambiguity” (Compact 2020: 7). This pillar is often underpinned by paranoiac behaviour: because conspiracy theorists are supposedly aware of hidden secrets, they are “not content with denouncing this or that conspiracy, real or imagined [..] on the contrary, the conspiracy becomes the systematic and systemic grid through which the whole of human history is read and interpreted” (Giry 2017).

This three-part typology provides a mechanism of categorization that conceptualizes the boundary work that narratives perform in the elaboration of conspiracy theories and simplifies the identification of narrative elements by framing their distinctive features. It will therefore help us determine whether the “Turkey story” can be classified as a conspiracy theory

The final stage studies the interaction between the overall political context, the image of the speaker and the choice of storytelling elements. Feldman et al. (2004: 154) propose a three-level analysis. The first level consists in identifying the storyline. The objective here is to determine the type of narrative archetypes being used to convey political ideologies and worldviews. Seargeant (2020: 87) argues that the two most relevant archetypes in political narratives are what he calls “rags to riches”, which is an initiatory trip in which the speaker acquired the wisdom to lead a community, and “overcoming the monster”, in which a community is being threatened by some evil force and, in response, a hero sets out to fight and eventually defeat this monster. The second level of analysis consists in establishing the opposition(s) in the story because, according to Feldman et al. (2004: 155) “looking for oppositions allows the researcher to uncover the meaning of a key element of the discourse by analysing what the narrator implies the element is not”. The third and final level of analysis consists in determining the argument at the heart of the story. In other words, the objective is to “reproduce the story in the form of syllogisms, logical arguments that help the storyteller express the ideas in the story”, in order to explicit the storyteller’s arguments. Very often, one part of the logical reasoning is left for the hearer to imply, which reinforces the persuasive effect of truncated syllogisms, or enthymemes.

2. Key findings: The narrative boundaries of a potential Brexit conspiracy

2.1. Speech circumstances

The abundant literature on the 2016 referendum often highlights the very negative tone of the Brexit campaign, which was “divisive, antagonistic and hyper-partisan…” (Moore and Ramsay 2017: 168). The debate became extremely emotion-driven (Rivière-De Franco 2017) and both camps accused each other of lying and dishonesty. Marshall and Drieschova (2018: 91) argue that the referendum campaign was shaped by post-truth politics, which is “a politics which seeks to emit messages into the public domain which will lead to emotionally charged reactions, with the goal of having them spread widely and without concern for the accuracy of the messages provided” (ibid.: 90). This form of politics, they explain, has been made possible by two recent developments: the growing and widespread usage of social media for acquiring information and a growing distrust in traditional elites as well as expertise (ibid.: 92). Against the backdrop of exacerbating political tension and within weeks of the vote, Vote Leave decided to change its strategy and focus on immigration, in place of the economic argument they had promoted at the beginning of the campaign, but which had failed to provide a clear alternative to the EU’s economic advantages (Clarke et al. 2017: 53). This is when several stories about Turkey being on the verge of entering the EU began to emerge in the Vote Leave literature.

2.2. Pillar 1: A group of conspirators secretly act behind closed doors

The first pillar rests on three main elements. First, the belief that events are secretly manipulated, behind the scenes, by powerful and malevolent forces. This is at the heart of the conspiracy theory dogma. Second, a plot is being orchestrated by an opaque organisation which aims to promote its own interests, to the detriment of the common good. Those so-called “conspirators” are therefore enemies of the people, which enables conspiracy theorists to divide the world between good and evil, using basic “us vs. them” rhetoric (Wodak 2021: 8). Third, conspirators supposedly try their best to hide their purposes, which reinforces “the assumption is that if you dig deep enough, you will find hidden connections between people, institutions and events that explain what is really going on” (Compact, 2020: 4).

Vote Leave’s rhetoric seems to draw on some of these elements. The most prominent argument is the fact that the EU is working against the interests of the UK and might actually take decisions that British people did not approve of and did not vote for. The EU is therefore depicted as an undemocratic organisation whose decisions have a negative impact on regular British citizens. The following three examples are quite significant:

The Government has failed because of the simple reality that inside the EU we cannot control immigration - it is literally impossible because we have no choice but to accept the principle of free movement and the European Court has ultimate control over our immigration policy […] the Prime Minister’s deal has given away control of immigration and asylum forever […] the rogue European Court now controls not just immigration policy but how we implement asylum policy under the Charter of Fundamental Rights. And, on top of all of this, new countries are in the queue to join the EU and the EU is extending visa-free travel to the border of Syria and Iraq. It is mad (CO8).

Nearly ninety million people in Turkey and four Balkan countries are being lined up for free movement followed by EU membership […] if those countries join, EU migration is forecast to go over 400,000 a year by 2030, that is a city the size of Bristol every 12 months. Meanwhile, control of our borders will ebb away to Brussels. Unaccountable EU judges already stop us turning away criminals or people who come here without a job, despite Cameron saying he could win curbs to unrestricted freedom of movement. The judges are now extending their power so they control immigration to Britain from outside the EU (CO13).

Inside the EU we have to accept that anyone with an EU passport - even if they have a criminal record - can breeze into this country. That will include countries in the pipeline to join the EU - Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey (CO2).

The overall storyline in these three representative examples reads like a study in failure – or a Greek tragedy: the UK is battling against powerful and malevolent forces trying to subdue its legitimate will to control its external borders, but however hard it may try, the UK, as a nation, is doom to fail. An aggravating factor is the secret complicity of the UK government, as “the Prime Minister’s deal has given away control of immigration and asylum forever” (CO8). The omnipotence of what VL consider as “villains” is highlighted by the fact that even the duly elected UK government has “no choice but to accept” decisions over EU immigration, and beyond. The lack of legitimacy and credibility of what amount to “conspirators”, in the conspiracist creed, are being discursively reinforced, as the European Court is a “rogue” (CO8) organisation and EU judges are “unaccountable” (CO13).

There are several key oppositions: the UK vs. the EU obviously, but also political legitimacy vs. authoritarianism and more importantly, as far conspiratorial studies are concerned, accountability vs. a clear lack of EU transparency. The main argument developed in this first pillar, we argue, can be summarized in the following enthymeme: sound democracy rests on accountability and transparency (major); the EU cannot be held into account (minor); the EU is therefore not a democratic institution and the UK should leave (implicit conclusion). It should be noticed that although the major and minor premises are explicit, the conclusion is not and is left for the audience to imply.

It seems, however, that one essential element is missing from this first pillar, as no stated – and more importantly, hidden – purpose is mentioned. The EU and the UK government are not working in the best interest of the UK population, but Vote Leave members do not give any explicit motive for this. We might assume that it is in order to subjugate Britain, but this is not clearly stated. The conspirators are therefore not trying to hide their objectives, as no objective is given, and if the EU is indeed depicted as a powerful and malevolent organisation trying to manipulate events to the detriment of the UK, it is done in plain sight.

2.3. Pillar 2: Nothing is as it appears, people are being lied to

In line with the previous pillar, which assumes that powerful and malevolent forces manipulate events behind the scenes and try to hide their evil purposes, conspiracy theorists claim that you need to look beneath the surface to see the truth. Their role is thus to decipher the lies of the conspirators so as to unveil the truth and, even if they are often stigmatized, conspiracy theorists usually “take comfort from the idea that – unlike the rest of the population – they have woken up and understood what is really going on” (Compact 2020: 6-7).

We saw that Vote Leave members accused the government of being in collusion with the EU over “uncontrolled” immigration, which reinforced the fear that official politicians were teaming up with occult forces to work against the general interest of British people. In a Telegraph article (CO14), senior political correspondent Tim Ross defended the idea that the government’s handling of immigration was detrimental to the UK population:

For the first time, a government report reveals the full impact of years of immigration from Europe on the state education system, at a time of growing strain on classroom places […] Priti Patel, the employment minister and a member of the Leave campaign, warned it would get worse, with countries including Turkey “in the pipeline” to join the EU […] the official estimates emerged at a critical time in the battle over Britain’s future in Europe, with the referendum campaign about to enter an intense final six weeks […] the latest government figures, released by the Government’s chief statistician, John Pullinger, were published without fanfare last week on Parliament’s website, on a page listing papers deposited in the House of Commons library. It follows a row last month when ministers were attacked for refusing to publish an investigation into the impact of migration on state schools until after the referendum. More than a year ago, Nicky Morgan, the Education Secretary, launched a major government review into the issue, and promised before the election to provide extra help for teachers who have to cope with new pupils who do not speak English […] however, the Telegraph disclosed in April that Mrs Morgan would not publish the findings of the report until after the referendum on June 23 at the soonest, and may not publish them at all (CO5).

This is the story of selfless and patriotic politicians trying to uncover what the UK government is attempting to hide from the public. In what amounts to political betrayal of public trust on the part of the government, Vote Leave members claim to reveal a truth that UK officials would prefer to hide. The UK government is not directly accused of lying about immigration, but they voluntarily try to mislead the British public by publishing discreetly (“without fanfare”) the latest official figures on the subject. The narrative twist comes with the claim that the government is supposedly withholding a damning report until after the referendum, which entails that it would be bad publicity for the Remain campaign – which means that official authorities are biased and promoting the In-campaign. As the report is not being published, Vote Leavers assume that immigration has a very negative impact on state schools, even if the claim cannot be corroborated by facts. However, Vote Leavers do not accuse the government of lying directly. Instead, they pretend that the government is lying by omission, which fuels suspicion and reinforce the idea that the safer choice is to leave the EU altogether.

The clear set of oppositions is between good and decent British people vs. the deceitful UK government; between truth and lies and quite significantly, between public trust and political dishonesty and potential covering up. The line of argument put forward here is that sound government is about transparency (major); the EU’s immigration conundrum is forcing the UK government to lie by omission (minor); real transparency is not achievable as long as the UK is part of the EU, so the UK should leave to safeguard democracy in the country (implicit conclusion).

The “Turkey story” developed by Vote Leave members, and the general narrative about uncontrolled EU immigration, seems to fit in with the second pillar of Soteras’ typology, but only to a certain extent. Indeed, in a similar vein to the first pillar, it is not possible to find all the defining features of this second pillar. Here, Vote Leave members do not assert that people are directly being lied to. Instead, it would be more accurate to say that their claim is that people are being misled and that the political elite is voluntarily selective with the truth.

2.4. Pillar 3: Everything is connected, nothing happens by accident and there are no coincidences

The conspiracy creed seems to rest on a deterministic approach to how the world works. Giry (2017) argues that “the conspiratorial approach is concerned with gathering and ordering, within a unique and coherent narrative framework, scattered facts and events which, a priori, do not make sense together […] the intention is to provide proof that the facts and events in question are necessarily linked, because they result from a single cause, i.e. a conspiracy”.

This third pillar does not seem to be predominant in the “Turkey story”. What is nonetheless interesting is that what is being connected is the link between mass immigration and the current difficulties of the public services, in particular the school system and the NHS:

On Monday, parents across the UK will be told whether their children got into their primary school of choice. Tens of thousands are expected to be told that they will not obtain their first preference. Membership of the EU means we are completely unable to control EU migration, and that puts unsustainable pressure on school places. This will only get worse with five more countries - Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey - in the pipeline to join the EU. The fact is, the UK has to pay £350 million to the EU every week - if we Vote Leave we can take back control over that money and reinvest it in our vital public services (CO1).

As we have set out before, it is government policy for five new countries to join the EU: Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey. We are paying billions to these countries to help them join. The EU is already opening visa-free travel to Turkey. That would create a borderless travel zone from the frontiers of Syria and Iraq to the English Channel. The EU’s plans for future growth will lead to demands being placed on the NHS far beyond what its funding can cope with (CO11).

The storyline is that the EU is a failed institution that is incapable of regulating internal migration, which dramatically affects the lives of EU citizens. This is once again a tragedy that befalls regular British people. The opposition is between vulnerable British people and highly technocratic, yet inefficient, EU bureaucrats. The logical structure is that sound governance should provide strict immigration control (major), but the EU has no control over immigration (minor), so the EU is politically irresponsible and should be left (implicit conclusion).

In terms of political economy, as those two examples are extracted from speeches delivered by senior Conservative MPs Priti Patel (CO1) and Michael Gove (CO11, along with Boris Johnson and Gisela Stuart as signatories), we argue that linking Turkey’s potential entry into the EU and the ailing public sector in the UK might amount to a deliberate use of the so-called “dead cat strategy” (Clarke et al. 2015; Gaber and Fisher 2022 developed by Tory spin doctor, Lynton Crosby. A shocking announcement is made in order to divert media attention from an embarrassing situation, as Boris Johnson (2013) put it:

Let us suppose you are losing an argument. The facts are overwhelmingly against you, and the more people focus on the reality the worse it is for you and your case. The solution is to perform a manoeuvre that a great campaigner describes as ‘throwing a dead cat on the table, mate’, the aim of which is to distract your onlookers to the point where they will be talking about the dead cat, the thing you want them to talk about, and they will not be talking about the issue that has been causing you so much grief.

Scholars and journalists alike tend to link the sorry state of the public sector in the UK, in part, to the budget cuts of the Cameron government and the so-called austerity policy imposed by then Chancellor George Osborne (Bach 2016; Emery and Iyer 2022; Campbell 2022). We might assume that creating a connection between Turkey’s potential entry and the pressure on public services that it would entail is a strategy not to talk about the Conservatives’ record, while blaming the EU for the current situation.

Once again, the “Turkey story” does not seem to fit in perfectly with Soteras’ pillars. If Vote Leave members show that there is a link between Turkey’s entry and the difficulties of the public sector, there seems, however, to be no “unique and coherent narrative framework” which would emerge from an EU conspiracy aiming to grant Turkey access to European organisation. The connection being drawn here between Turkey and the UK public sector seems rather to be purely political, to fuel resentment at the EU and divert attention from the consequences of the economic measures taken by the Conservative government, and not an EU plot to destroy the UK service sector.

Conclusion

The idea that Turkey was on the verge of entering the EU, which would give millions of Turks access to the UK ailing public sector, and that the only way to avoid this situation was to vote to leave the EU before it was too late, reads like a powerful story indeed. In terms of narrative archetype, the “Turkey story” falls within Seargeant’s “overcoming the monster” category (2020: 87). As such, the narrative structure is straightforward: the EU, as the “enemy”, has devised an evil plan – to let Turkey enter the supranational organisation – which will be detrimental to the British nation, and more generally, to Britishness. This desperate situation calls for “heroes” to intervene and right the wrongs. Vote Leave members take on this role by uncovering the EU’s Machiavellian plan and revealing the UK government’s collaboration.

The oppositions are somewhat revealing of populist undertones (Wodak 2021) on the part of Vote Leave: the EU elite vs. the regular British people; the collaborating UK government vs. the Vote Leave whistle blowers; lack of accountability vs. transparency and more importantly, tyranny vs. democracy. The overall enthymemic framing of the “Turkey story” could be summarized as: sound politics is about trust (major); the potential entry of Turkey is hidden by EU politicians (minor); the EU cannot be trusted and therefore should be left (implicit conclusion). Other syllogisms could also be elaborated. A more ethnocentric argument could be: Europe is a Judeo-Christian continent; Turkey is a predominantly Muslim; Turkey’s entry will upset the cultural balance of the continent. Last but not least, a Britain-centred argument would read as: the UK civil services are in a poor state; Turkey’s entry would increase the burden on the UK civil services to breaking point; the UK should leave the EU to safeguard the UK civil services.

This narrative analysis reveals the rhetorical potential of the “Turkey story”. However, determining whether this amounts to a conspiracy theory or whether it could be considered as mere disinformation – and “strategic lying” – is not as straightforward as one might expect at first. The EU, with the help of the UK government, is making decisions that are deemed negative for the UK population. Vote Leave members therefore assume that a powerful elite is working against the interests of regular people. Such “us vs. them” narrative is usually at the heart of conspiracy theories rhetoric (Wodak 2021: 8); however, no ultimate motive seems to emerge to explain the “secret” ambitions of the EU. Besides, the EU and the UK government are not directly lying to British people, they are simply withholding the truth, or just showing part of it. Still, Vote Leave members, in a move reminiscent of conspiracy theorists, do try to connect the dots in order to question the overall aim of the EU and the reasons why the UK government is supposedly not being straightforward with British people. Last but not least, a connection is being created between Turkey’s entry and the current difficult situation of the public sector in the UK, but once again, it seems to be more of a political argument rather than telling evidence of a conspiracy theory. The “Turkey story” proved nonetheless useful during the referendum as it allowed Vote Leave members to focus on emotional topics, rather than technical – and dull – arguments, like the Remain campaign (Schnapper 2017).

To answer the initial research question, we might argue that Vote Leave members created some form of rhetorical continuum between conspiracy theories and strategic lying, in what might amount to “strategic conspiracy”, or simpler, “Brexit conspiracy”. They used some important elements of the conspiratorial creed in order distort reality in a way that was beneficial to their cause, as “populist politicians often use conspiracy theories strategically in order to mobilise their followers” (Compact, 2020: 5). What seems to make the “Turkey story” tilt slightly towards strategic lying rather than conspiracy theory, however, is the rapidity with which some prominent Vote Leave members distanced themselves from it (Worrall 2019). Its emotional appeal made it relevant during the referendum, but the plain lies it was built on, and the racism it carried, made it toxic for politicians aspiring to have an important role in the UK government after the referendum.