We thank the editors and guest-editors of ELAD-SILDA and two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped to improve this paper. Parts of this work have been discussed at the International Conference “Adverbs and Adverbials: Issues in semantic and functional ambiguity” (Nicosia, Cyprus, 18‑19 May 2023). We thank the participants for comments and feedback. All remaining errors are our own.

Introduction

In this paper, we analyze two intra and cross-linguistically cognate pairs of adverbials: Portuguese (Pt.) and Spanish (Sp.) por completo and completamente, both meaning ‘completely’ in both languages (for Spanish, see, e.g., NGLE: § 30.8; GDLE: § 4.2.2.2, 37.6.5; for Portuguese, see, e.g. Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. completamente). The Spanish and Portuguese adverbials are cross-linguistic cognates insofar as they are all based on the Latin deverbal adjective complētus ‘complete, in its entirety’. Furthermore, we consider that Sp. por completo is an intra-linguistic cognate of Sp. completamente, as well as Pt. por completo is an intra-linguistic cognate of Pt. completamente. I.e., the adverbial prepositional phrases formed by the pattern “preposition + adjective” (PA) are cognates of their derived adverbial counterparts formed with the suffix ‑mente (for this use of the term “cognate”, see also Gerhalter and Koch submitted; Koch and Vecchia accepted; Mirto, 2018, 2022).

The adverbials por completo and completamente are synonymous, respectively, in Spanish and Portuguese. Moreover, they share the same functions in these languages, i.e., they are equally polyfunctional: they can be aspectual quantifiers and degree quantifiers. As aspectual quantifiers, they mainly modify verbs that denote telic, process-related events that imply an end (see GTG: s.v. adverbio de aspecto). For example, por completo and completamente indicate a resultative completion at a certain maximum stage or degree of the action/event expressed by verbs such as Sp. cambiar (examples 1 and 2) or Pt. mudar (examples 3 and 4), both meaning ‘to change’:

| (1) | Es extraño, pero cierto. Entre 1914 y 1919 la vida cambió completamente […]. Me desperté famosa en 1919. | (Spanish) |

| “It is strange, but true. Between 1914 and 1919 life changed completely […]. I woke up famous in 1919.” (CDH, 1997, Inmaculada Urrea: Coco Chanel. La revolución de un estilo) | ||

| (2) | La brújula, dentro de su sencillez, es tan maravillosa que, cuando se inventó (o se descubrió su principio básico), llegó a cambiar por completo la estructura del mundo conocido, porque facilitó la seguridad en la navegación y activó los grandes descubrimientos geográficos. | (Spanish) |

| “The compass, in all its simplicity, is so wonderful that when it was invented (or its basic principle was discovered), it completely changed the structure of the known world, because it facilitated safe navigation and made the great geographical discoveries possible” (CDH, 1999, Agustín Faus: Andar por las montañas) | ||

| (3) | A revolução tecnológica recente mudou completamente a forma de trabalhar e permitiu novas formas de organização empresarial à escala global. | (Portuguese) |

| “The recent technological revolution has completely changed the way we work and enabled new forms of business organization on a global scale.” (CdP, 1997, Thomas Malone, especialista do MIT) | ||

| (4) | Quando ele abriu a porta e fez entrar os hóspedes, a sua atitude mudou por completo: dirigiu-lhes um largo sorriso, deu-lhes as boas-vindas. | (Portuguese) |

| “When he opened the door and let the guests in, his mood changed completely: he gave them a broad smile and welcomed them.” (CdP, 1986, João Aguiar: O homem sem nome) | ||

Additionally, por completo and completamente are used as degree quantifiers, for example of adjectives, such as Sp. solo ‘alone’ (ex. 5 and 6) or Pt. livre ‘free’ (ex. 7 and 8). As such, they express a high or the maximum degree of a gradable property of the lexical unit in their scope (see Souza and Foltran, 2020):

| (5) | Mientras el tren permaneció allí tuve la sensación de que no estábamos solos por completo. | (Spanish) |

| “As long as the train remained there I had the feeling that we were not completely alone.” (CDH, 2002, Gabriel García Márquez: Vivir para contarla) | ||

| (6) | Me gustaba imaginarme sobre una duna en un desierto, completamente solo, como un indio o un cowboy | (Spanish) |

| “I liked to imagine myself on a dune in the desert, all alone, like a Native American or a cowboy.” (CDH, 1998, Patricia de Souza: La mentira de un fauno) | ||

| (7) | Meteu-se na grande orgia, para se convencer de que estava livre, livre por completo. | (Portuguese) |

| “He joined the great orgy to convince himself that he was free, completely free.” (CdP, 1910, Brazil, João do Rio: Dentro da noite) | ||

| (8) | É uma inclinação que me vem da infância e que acabou entrando em conflito com outra obsessão minha não menos intensa: a de ser completamente livre. | (Portuguese) |

| “It’s an inclination that comes from my childhood and ended up clashing with another obsession of mine that is no less intense: that of wanting to be completely free.” (CdP, 1961, Brasil, Eric Verissimo: O tempo e o vento, Parte 3, Tomo 2) | ||

In the present paper, we discuss the extent to which and the contexts in which por completo and completamente function as degree quantifiers, as well as how this secondary function develops diachronically based on their original function as aspectual quantifiers. We also analyze if there is a change in syntactic scope (verb-modification vs. adjective-modification) and position (before vs. after the modified element). We will describe the diachronic evolution of por completo and completamente in terms of Himmelmann’s (2004) context expansion on three levels: host-class expansion, semantic-pragmatic context expansion, and syntactic context expansion. We will also examine if there are bridging and switch contexts (according to Heine, 2002), or critical and isolating contexts (according to Diewald, 2002), respectively, in this evolution.

This endeavor raises further questions concerning (i) when this evolution occurred, (ii) if there are differences between Spanish and Portuguese, and (iii) if the diachronic developmental paths are similar for por completo and completamente. The latter, (iii), is of special interest, since diachronic studies on quantifiers so far have focused on mente-adverbs (e.g., on Spanish, García Pérez, 2022; Pérez García and Blanco, 2022; on Portuguese, Foltran and Souza, 2020). In contrast, the present study focuses mainly on PA, contrasting them with mente-adverbs. For example, the cognates can differ regarding the syntactic position: in examples (6) and (8), the degree quantifier Sp./Pt. completamente is placed before the modified adjectives (completamente solo/completamente livre), whereas Sp./Pt. por completo seems more natural after the adjectives (solos por complete/livre por completo), as in (5) and (7).

We draw on data from the Portuguese Corpus do Português (henceforth and in the bibliography CdP), as well as from the Corpus del Diccionario Histórico de la Lengua Española (henceforth and in the bibliography CDH) and the Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI (CORPES XXI) for Spanish. Although we take into account both languages parallelly, the analysis of the Spanish data will sometimes be more detailed than the analysis of the Portuguese data, due to the fact that the two Spanish corpora, at this point, are more elaborate than the Portuguese corpus, e.g., when it comes to the exact dating of historical examples (CDH) and to fine-grained search queries of specific patterns (CORPES XXI). Also, CDH is based on a larger database (355 Mio words) than the historical section of CdP (“Genre/Historical”: 45 Mio words).

This paper is structured as follows: We first present the theoretical framework of our study (Section 1) and then shortly discuss the etymology and the origins of the Sp./Pt. adjective completo, as well as the Sp./Pt. adverbials completamente and por completo (Section 2). In Section 3, we analyze the data provided by the corpora and look at the different diachronic steps in the evolution of the adverbials (e.g., regarding syntactic scope, syntactic position, and possible bridging/critical and switch/isolating contexts). In Section 4, we discuss the chronology of the assumed context expansion, the effect of whole paradigms of adverbs with similar meaning, function and syntactic position on an individual adverb’s evolution, and semantic restrictions of the context in which the studied quantifiers can occur.

1. Theoretical framework

In (1.1) we discuss the distinction and the overlap between aspectual and degree quantifiers, and in (1.2) we present a framework for the role context plays in semantic change.

1.1. Aspectual and degree quantifiers

We follow the classification proposed by Kaul de Marlangeon (2002: 123-145), who considers aspectual adverbs a subcategory of quantifier adverbs. The Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española (NGLLE), too, despite distinguishing between Sp. adverbios de aspecto ‘aspectual adverbs’ (§ 30.8) and cuantificadores ‘quantifiers’ (§ 30.4), observes that aspectual adverbs are, indirectly, also quantifiers (§ 30.4p-q). As for Sp. completamente, the Gramática de la Lengua Española (GDLE; therein § 37.6.5.1) sustains that, in some cases, it behaves like an aspectual adverb and in some cases like an adverbio de grado (‘grade adverb’, i.e., degree quantifier in our terminology).

The paradigm of aspectual quantifier adverbs in Spanish and Portuguese comprises mainly completamente ‘completely’, totalmente ‘totally’, enteramente/inteiramente ‘entirely’, plenamente ‘fully’ and parcialmente ‘partially’ (Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 158; NGLLE § 30.8; Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. completamente). According to NGLLE (§ 30.8) and GDLE (§4.2.2.2; 37.6.5), these adverbs modify telic verbs with process-related semantics, i.e., verbs that typically denote a gradual process with an inherent endpoint. More precisely, completamente and por completo modify such verbs in the sense that the action/event expressed by the verb is executed until completion, as in examples such as Sp./Pt. cambiar/mudar completamente/por completo ‘to change completely’. Aspectual adverbs are therefore quantifiers insofar as they quantify the degree to which a telic process is completed, or designate that its inherent endpoint is reached (Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 141-142). There is always a maximum or an endpoint in closed scales, e.g., if a work is completed, nothing else can be added, or if a glass of water is completely (100%) full as the result of filling it, no more water can be added without spilling it, i.e., the glass can never be ‘over-full’ (see the discussion in Fábregas, 2015: 249).

Furthermore, aspectual completamente modifies participles and ‘perfective’ adjectives (i.e., adjectives that are related to telic actions/events, see GDLE: § 37.6.5.2), and highlights the process-related ‘perfection’ or ‘completeness’ of the property denoted by such an ‘perfective’ adjective. This property itself is also supposedly the result of or caused by an underlying process still inherent in the adjective’s semantics. For example, completamente limpio ‘completely clean’ can be interpreted as the result of the telic, process-related event of cleaning (e.g., GDLE: § 37.6.5.1). This example, though, raises the question if, in such contexts, completamente basically simply remains aspectual, or if indeed a high degree reading (‘very clean’) is foregrounded instead.

In some instances, such as in completamente loca ‘completely crazy’, completamente does arguably not express aspectuality (GDLE: § 37.6.5.1), because the state loca ‘crazy’ is not gradually completed or reached, i.e., it is probably not the result of a telic process (though some might argue that, to be crazy, you need to become crazy). Instead, in these cases, completamente expresses mainly a very high degree, or the maximum degree, of a property or a state. It enters (the same is valid for por completo in such contexts) the paradigm of degree quantifiers that intensify (in the sense of high quantity or high degree) the semantic property/properties denoted by the modified element on a gradual scale (intensificación del grado ‘degree intensification’; see Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 132-134, 158). This paradigm of degree quantifiers is formed by adverbs such as Sp./Pt. absolutamente ‘absolutely’, increiblemente/incrivelmente ‘incredibly’, extremadamente/extremamente ‘extremely’, altamente ‘highly’, excesivamente/excessivamente ‘excessively’, fuertemente/fortemente ‘strongly’, enormemente ‘enormously’, among others. These intensifiers are opposed to adverbs such as Sp./Pt. escasamente/escassamente ‘scarcely’ or poco/pouco ‘little’, which express attenuation/mitigation or diminution (Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 134, 158).

In principle, the semantics of the modified element (verb or adjective) determines the interpretation of completamente and por completo as either aspectual or as degree quantifiers. The aspectual reading with verbs is primarily foregrounded when the lexical aspect of the verb is telic. However, there are cases in which completamente and por completo are ambiguous between a reading as aspectual quantifier and a degree quantifier: depending on the broader context, Sp. está completamente roja ‘she is completely red’ may be interpreted either as the result of having blushed completely (aspectual) or as expressing a very high (momentary) degree of redness (GDLE: § 37.6.5.1). Other examples might be also interpreted as having both readings simultaneously. As the blushing/redness-example shows, the degree reading and the aspectual reading (completion of a telic process) are closely related.

In such ambiguous cases, the broader context of the sentence may help to disambiguate: e.g., Sp. quedarse completamente solo and Pt. ficar completamente sozinho ‘to be left completely alone’ are interpreted predominantly as aspectual (culmination of a process over time). Contrarily, in Sp. sentirse completamente solo/Pt. sentir-se completamente sozinho ‘to feel completely alone’, the foregrounded reading is probably, in most contexts, that of a high or maximum degree (‘extremely/very alone’). Similarly, Kaul de Marlangeon (2002: 142) states that, in sentences such as Sp. La región está completamente seca/Pt. A região está completamente seca ‘The region is completely dry’, the aspectual adverb indicates the final result of the gradual process of drying out over time. Contrarily, in Sp. La región es completamente seca/Pt. A região é completamente seca ‘The region is completely dry’ the state of being dry is not necessarily the result of a process, but the quantifier completamente expresses the maximum possible degree of the quality ‘dry’. This difference is obviously related to the difference in the verbal semantics of the Sp./Pt. copula ser and estar, the former designating permanent states and the latter transitory ones.

To sum up, por completo and completamente are aspectual quantifiers if the element in their scope somehow expresses a telic process that develops over time and can be completed when a final maximum state or endpoint is reached. As degree quantifiers, in principle, they modify any element that has scalar semantic properties. However, as we will show, there are some restrictions for the use of completamente and por completo as degree quantifiers. These restrictions are based on the fact that the attribution of quantity is almost always implicit in the lexical semantics of adverbs that are used as degree quantifiers (according to Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 134). For example, Sp./Pt. altamente ‘highly’, apart from expressing the property of ‘high’ or ‘high above’, is also always, due to this lexical semantics, quantitative in nature. I.e., such adverbs potentially retain qualitative and quantitative properties in their lexical semantics (see also Hummel, 2012, on polyfunctional and polysemous adverbs).

Since, in the specific case of completamente and por completo, the aspectual and degree interpretations largely overlap, we sustain that they cannot be considered truly polysemous. Instead, the two interpretations (aspectual or degree quantifier) should better be considered contextual variants of the core meaning ‘complete’. Rather than speaking of polysemy, polyfunctionality1 is a more appropriate term: por completo and completamente are polyfunctional regarding their adverbial functions (aspectual quantification vs. degree quantification) and regarding their syntactic scope (modification of a verb vs. modification of an adjective).

The interpretation as either aspectual or degree quantifier is not linked to a certain syntactic scope, i.e., both interpretations are possible with both verbs and adjectives in the scope of the quantifier. Therefore, an adjective, through its specific semantics, and depending on the context, can, for example, trigger either an aspectual-quantifier-reading (Sp. dejar completamente limpio/Pt. ficar completamente limpo ‘to leave/to become completely clean’) or a degree-quantifier-reading (Sp. sentirse completamente solo/Pt. sentir-se completamente sozinho ‘to feel completely alone’) in the adverb that modifies such an adjective. Accordingly, a verb can also trigger either an aspectual reading, like in Sp. cambiar completamente/Pt. mudar completamente ‘to change completely’, or a degree-quantifying reading, like in Sp./Pt. ignorar por completo ‘to ignore completely’, the latter not being a telic process, but a durative ‘state’.

Concerning syntactic positions, we adopt a scopal approach to adverb placement (Ernst, 2002), which allows for right and left adjunction, i.e., adverbs appear wherever they are ‘needed’, be it left or right of the modified element, and according to the syntactic rules in place for their specific type (adverb vs. adverbial prepositional phrase) in combination with the word class of the syntactic elements in their scope. We do not assume preliminarily fixed syntactic positions as advocated by Cinque’s (1999) cartographic approach.

In general, quantifiers in the Romance languages are usually placed directly before the modified element, except when modifying verbs, where they tend to be placed after the verb (Ilari, 2007: 161, 167-168 on Brazilian Portuguese). Similarly, Kaul de Marlangeon (2002: 126) states that quantifiers are pre-posed to adjectives, nouns, and adverbs, but generally post-posed to verbs in Spanish. As for participles, the quantifiers are pre-posed when the adjectival reading prevails, like in Sp. totalmente aclarado/Pt. totalmente esclarecido ‘totally clarified > totally clear’, and post-posed when the verbal reading is foregrounded, like in aclarado/esclarecido totalmente ‘totally clarified’ (see Kaul de Marlangeon, 2002: 126 on Spanish).

1.2. On the role of context and context expansion in language change

As largely discussed by many authors (e.g., Diewald, 2002, 2006; Heine, 2002; Smirnova, 2015; for a recent take on the matter, see Schneider, 2024), language change does not affect isolated lexemes, but lexemes in their context, i.e., as part of constructions (not necessarily in the narrow sense of Construction Grammar). To describe the evolution of the adverb(ial)s under scrutiny with regard to the context in which they appear, we follow the concept of context expansion on three different levels, as proposed by Himmelmann (2004: 32-34):

- Host-class expansion: the class of elements a word co-occurs with (i.e., the host-class, e.g., proper names) may be expanded by new classes of elements this word can co-occur with (e.g., all nouns), leading to new collocational patterns (see also Coussé, 2018 on the host-class expansion of the ‘open slot’ of semi-schematic constructions).

- Syntactic context expansion: the larger syntactic context and the position of a word may be expanded so that a word can occur in new syntactic contexts and new syntactic positions.

- Semantic-pragmatic context expansion: likewise, the semantic and pragmatic usage contexts may be expanded.

In this paper, we consider as host-classes three different categories of words that are modified by the adverb(ial)s por completo and completamente: verbs, participles, and adjectives. The syntactic context under scrutiny is specifically the immediate syntactic context of the adverbials (e.g., ser completamente seca vs. estar completamente seca), as well as the position of the adverb(ial)s with regard to the modified element (pre-position and post-position). Finally, the ‘semantic-pragmatic context’, in this paper, refers to different semantic traits of the modified verbs, participles, or adjectives in a specific context, e.g., culmination of a telic process, perfective adjectives, or adjectives that denote a gradual property with or without a maximum limit, as we will discuss in detail. We aim to analyze whether por completo and completamente show context expansion over time on these three levels, and whether the three levels are interrelated.

Although developed specifically for grammaticalization, Himmelmann (2004: 33) states that context expansion is a general type of language change that is not restricted to grammaticalization. Similarly, Schneider (2024) adapts the model of different context types that have been postulated to play a role in grammaticalization (untypical contexts > critical contexts > isolating contexts) to other patterns of language change. In the same vein, we refer to these context types to analyze the evolution of por completo and completamente, without considering this evolution a case of grammaticalization. We do so, as the evolution from an aspectual to a degree quantifier or the evolution from verb-modification to adjective-modification is not a change towards a more grammatical function. Moreover, several grammaticalization parameters postulated by Lehmann (2015: 129-188) do not apply in the case of the development of por completo and completamente: coalescence/bondedness, obligatorification, (positional) fixation, condensation of scope, and phonological attrition or erosion.

Concerning untypical, critical, and isolating contexts, as used by Diewald (2002, 2006) and Smirnova (2015), these concepts refer to the following successive stages:

- Untypical contexts: unspecific expansion of the distribution of the lexical unit in question to contexts in which it had not been used before; the new meaning may arise as a conversational implicature (Diewald, 2002: 103). This stage, called extensional by Schneider (2024), corresponds to the host-class expansion described above (Himmelmann, 2004: 32‑34; Schneider, 2024: 316).

- Critical contexts: multiple structural and semantic ambiguities invite for several alternative interpretations, among them the new meaning (Diewald, 2002: 103).

- Isolating contexts: specific contexts that favor only one reading to the exclusion of the other(s) (Diewald, 2002: 103); when this change is completed, the new meaning is isolated as a separate meaning from the older one(s), and the paradigm that is the target category (to which an item via its new meaning belongs) is reorganized. The item has become truly polysemous (Diewald, 2002: 103).

This model partially overlaps with Heine’s (2002) model of context-induced reinterpretation which focuses on semantic change. Starting with the initial stage (source meaning), he postulates the following stages: bridging context > switch context > conventionalization. One could apply Heine’s (2002) terminology to classify the semantic evolution from aspectual to degree quantification as follows:

- Bridging contexts are ambiguous contexts (Diewald’s critical contexts, 2002), where, in addition to the established source interpretation of a linguistic unit, a ‘new’, contextually inferred interpretation is possible, too (Heine, 2002: 84-85). Therefore, for our purposes, in addition to the aspectual reading, a degree reading can be inferred (e.g., Sp./Pt. completamente limpio/limpo ‘completely clean’, ambiguous between ‘clean as the result of cleaning’ or, depending on the context, ‘very clean’).

- Switch contexts are very specific contexts that isolate (see Diewald’s isolating contexts, 2002) the target meaning from the source meaning, which is then ruled out in the end in this context (Heine, 2002: 85). In this case, degree quantification is foregrounded in specific constellations, e.g., Sp./Pt. completamente loca/louca ‘completely crazy’ in contexts meaning ‘very/extremely crazy’, as opposed to constellations in which the aspectual reading is present like in Sp./Pt. volverse completamente loca/ficar completamente louca ‘to become completely crazy’. In some instances of this stage (switch context), the degree reading is already the only possible interpretation.

- The conventionalization stage is reached when the new interpretation becomes context-independent and can be used in contexts other than the ones characterizing bridging and switch contexts; the new interpretation turns into a ‘usual’ meaning (Heine, 2002: 85). If we assume this stage for por completo and completamente, then they should be able to modify any adjective with inherent scalar properties and could, syntactically and collocation-wise, freely alternate with other degree quantifiers such as Sp./Pt. muy/muito, altamente ‘highly’, excesivamente ‘excessively’, fuertemente/fortemente ‘strongly’, etc. (as we will see in Section 4.3., this is not the case).

2. General overview of the origins of completo, por completo, and completamente

Before analyzing the different steps in the semantic and syntactic evolution of completamente and por completo, we first need to look at the general diachronic panorama of the adverbs under scrutiny, based on historical linguistic dictionaries and corpus data.

2.1. The etymology of the adjective completo

The adjective completo in Spanish and Portuguese is a learned loan word from Latin (Sp. cultismo; see, e.g., Corominas and Pascual, 1996 [1980]: s.v. cumplir]), as it is in the other Romance languages and beyond, e.g., in English complete, or German komplett via the Romance languages, or via Middle/Renaissance Latin as a language of erudition. The etymology is Latin complētus, -a, -um, ‘full, filled (up)’, which is originally a past participle of the Latin verb cŏmplēre ‘to fill (up), to complete’ (see Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. completo; Corominas and Pascual 1996 [1980]: s.v. cumplir). Therefore, the original core semantics of completo, both in Spanish and Portuguese, refers to something that is totally and absolutely full and completed, and is therefore telic in nature, or linked to telicity. Hence, the etymological meaning of the adverbial cognates based on completo is the aspectual one. It, completo, means ‘completed’, in the first place, and only then, based on the first meaning, takes on the meaning ‘complete’.

The earliest use of completo in Ibero-Romance is the feminine plural form completas as lexicalized and substantivized ellipsis of horas completas ‘full hours’. Completas belongs exclusively to the religious discourse tradition and refers to the last prayer of the day according to the liturgy (Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. completa). In Spanish and Portuguese, this specific use is documented from the (late) 13th century on in the corpora CDH and CdP. In this ecclesial, and especially monastic discourse tradition, Latin was always present, also when denominating the hourly structure of the day, which facilitated this (semi-)cultism.

According to Corominas and Pascual (1996 [1980]: s.v. cumplir), Sp. completo as an adjective is a later loan word. In CDH, completo is documented as an adjective, in other contexts than horas completas, only from the 15th century on (ca. 1464).2 However, its hereditary, patrimonial cognate cumplido ‘fulfilled, perfected, accomplished’ (predominantly a participle, but also an adjective) is even attested already at the beginning of the 13th century: conplido (Poema de Mio Cid, 1140/1207), complido (omne complido, in the Fazienda de Ultramar, ca. 1200), and cumplido (en [la] cumplida corte, in the document Cortes de Benavente, 1202).

In Portuguese, the adjective completo appears later, for the first time in 1650, according to Houaiss et al. (2015: s.v. completo). This is consistent with the first documentations of completo in CdP in the 17th century. Again, the hereditary cognate cumprido/comprido ‘fulfilled/long’ is documented earlier (Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. comprido): comprjdo (1279), comprido (13th century), conplido (13th century), and cõprydo (14th century). Other variants documented in CdP are cõplido (15th century) and complido (16th century).

Unlike many other adjectives (see, e.g., Hummel, 2024: 404-412), completo is only marginally used as an adjective-adverb, i.e., with adverbial functions, but without any morphosyntactic markers of adverbiality like preceding prepositions or adverbial suffixes. In example (9), one of the few documentations in CDH, the aspectual quantifier Sp. completo modifies the verb Sp. transmitir ‘transmit’ and simultaneously conserves a predicative reading referring to the direct object, e.g., to the noun phrase el empuje de los remos (‘the thrust of the legs’):

| (9) | El ser ancha, recta y el estar bien unida á la grupa, son las bellezas absolutas de la region lombar, como que suponen condiciones mecánicas favorables á cualquier género de servicio. A ellas se debe el desarrollo, fuerza y resistencia de los lomos, como tambien la aptitud de trasmitir completo á las partes anteriores del tronco el empuje de los remos pelvianos ó posteriores. | (Spanish) |

| “Being broad, straight, and well attached to the rump, they are the absolute beauties of the loin region, as they imply favorable mechanical conditions for any type of service. They are the reason for the development, strength, and resistance of the loins, as well as for the ability to completely transmit the thrust of the pelvic or posterior legs to the front parts of the torso.” (CDH, 1881, Santiago de la Villa y Martín: Exterior de los principales animales domésticos y particularmente del caballo) | ||

As a modifier of adjectives, the adjective-adverb completo is also very scarce, since such an adjective-adverb can always be misinterpreted as an adjective itself in most cases. Some exceptions can be found, though:

| (10) | D. Carlos.— Pues no hagas caso de mí. Yo soy completo francés, Alegre, vivo, ligero: ¡Vaya! Si no hablo, me muero. |

(Spanish) |

| “D. Carlos: Well, don’t pay any attention to me. I am a complete Frenchman/I am completely French cheerful, lively, easy-going: Come on, if I don’t speak, I’ll die.” (CDH, 1845, Fernando Calderón: A ninguna de las tres) |

||

But even in (10), the interpretation is ambiguous concerning the modified element francés ‘French’, since the latter can be either a noun (> ‘a complete Frenchman’), which can easily license completo as an adjective in pre-position – and therefore completo wouldn’t surprise in its adjectival form –, or an adjective (> ‘completely French’), where indeed an adjective-adverb to the left of the modified adjective would be a rare attestation. One may suspect that this ambiguity is a factor for why such cases cannot be found too often in the first place.

Since the adverbial use of completo, as we have just seen, is marginal, we focus on the adverbials por completo and completamente.

2.2. The origins of the adverb completamente

The adverb completamente is formed by the feminine singular form of the adjective (completa) and the derivational suffix ‑mente. This suffix overtly marks the grammatical status of the word as an adverb. It is the most common way of deriving de-adjectival adverbs in the Romance standard languages except for Romanian (see Hummel, 2024: 413-418). This specific adverbial mark makes ‑mente-adverbs (mente in what follows), in general, highly flexible from a syntactic point of view: they can freely take almost any syntactic position in a sentence, and they can modify any syntactic constituent in Spanish and Portuguese (Martelotta, 2012; Raposo, 2013: 1600-1603; Company Company, 2014: 460-467; Company Company, 2018: 605).3

Mente form a (semi-)open class, since almost any Sp. or Pt. adjective can be used as a derivational basis (e.g., for Portuguese, Basílio, 1998; Raposo, 2013: 1579-1580). From a diachronic point of view, mente are the result of a morphological univerbation of Lat. noun phrases of the type A + N, e.g., san-ā (healthy-abl.f.sg) + ment-e (mind/sense.f-abl.(f).sg) ‘with a sound mind’ > e.g., Sp./Pt. sanamente ‘healthily’ (e.g., Karlsson, 1981: 47, 142). Their functional and semantic evolution is widely analyzed in terms of grammaticalization (e.g., for Portuguese, see Pinto, 2008; Silva, Carvalho and Almeida 2008; for Spanish, see Company Company 2012a, 2012b, 2014).

According to the data in CDH, Sp. completamente is first documented in 1408, i.e., even earlier than the adjective completo. This means that completamente is created (supposing derivation) approximately at the same time as the adjective completo (1464) itself is loaned into Spanish, as far as we can tell from the available data. This may suggest a prior parallel existence of both, obscured by the missing data from earlier centuries. The form based on the hereditary cognate cumplido, i.e., cumplidamente, is already attested in 1254.

In Portuguese, completamente appears three centuries later than in Spanish and is documented first in the 18th century in CdP. More precisely, according to Houaiss et al. (2015: s.v. completamente), the first attestation is from 1712. Once more, the patrimonial cognate, e.g., as cõplidamente, conplidamente, and cumpridamente (all 15th century), is attested earlier in CdP.

2.3. The origins of the adverbial por completo

The adverbial prepositional phrase por completo is an adverbial locution of the type “preposition + adjective” (PA), a productive pattern especially in earlier stages of the Romance languages (see, e.g., Hummel et al., 2019; Hummel, 2024: 418-422). In fact, as shown by Solari Jarque (2021, 2022), the PA pattern was already productive in Latin: for example, Lat. in vanum ‘in vain’ (cf. Pt. em vão; Sp. en vano), Lat. in brevi ‘in short’ (cf. Pt. em breve, Sp. en breve), and Lat. ad extremum ‘extremely’ (cf. Pt. ao extremo, Sp., today, en extremo). Individual PA-adverbials, as well as the productive PA-pattern itself, presumably were directly inherited by the early Romance languages (Hummel, 2019a: 147-148; see also García Sánchez, 2022: 7).

In the Romance languages, PA other than the inherited ones from Latin supposedly emerged as systematic and productive alternatives to adjective adverbs (even before mente appeared on a grand scale), enriching the inventory of Romance adverbials, from the Latin-Romance transition phase onwards, during the centuries of linguistic elaboration, at least until the 16th century (Hummel, 2019a: 156; 2019b: 308; see also Gerhalter, 2020a). However, beginning with the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, mente witnessed a steep rise in usage rates and productiveness (see Grübl, 2018; Bauer, 2003), and from the 17th century on, mente marginalized nearly all other types of adverb formation in the Romance standard languages such as Spanish and Portuguese. While some PAs lost ground (mainly to mente), others continue in present-day language as lexicalized adverbials (see, overall, Hummel, 2019a, 2019b). Nowadays, PA are generally less frequent than their mente-cognates and other means of adverb formation/creation (see, e.g., Gerhalter and Koch, 2020, on Brazilian Portuguese).

The Spanish PA por completo fits in this general panorama, but, contrarily to completo and completamente, it is first documented in Spanish only in the 17th century (1645). It seems that this PA was productively created in 17th century Spanish, since no precursor in Latin (*per complētum, *pro complētō, or any other combination with complētus) is documented in Solari Jarque (2021, 2022). If we took search results in CDH seriously, por completo would even be first attested already in 1485, or 1489, or 1507, but the years assigned to the corresponding tokens are erroneous. The attestation of por completo in CDH from 1485 is invalid, since it comes from a 1995 regest (i.e., a summary of the original document’s content by the Modern Age editor), which precedes the edition of a document redacted between 1485-1488 (see Ser Quijano, 1995). The other two (supposedly 1489 and 1507) are also useless for diachronic research. The first is a translation of a 15th century text in Arabic (a letter from Boabdil to the sheikhs of Ugíjar), translated between 1898 and 1910 by Mariano Gaspar y Remiro and edited by Miguel Garrido Atienza (1910: 188-189). The second is extracted from a historical treatise from 1908 (Rodríguez Villa, 1908: XLVIII-XLIX), in which some few citations from texts of the 1500s are included, but the part that contains por completo is simply a text written by the 20th century historian. This leaves only two examples from 1645 as valid first attestations (see example 12 for the first one).4

It is very eye-striking that the first legit attestations of por completo come from America: 1645 Mexico (2 tokens), 1747 Peru (2 tokens), and other colonies: 1754 Philippines (5 tokens), 1770 Philippines (1 token). Only then, the first authentic attestation from Spain is documented (1774, 1 token), followed by attestations from 1835, 1837 and 1843 (one token each, which are also the next attestations after 1774 in all the Hispanic world). The next documentation, again, is from the Americas: Chile 1845 (12 tokens). This goes very well along with Hummel’s (2019a) observation that quite a number of Spanish PAs are first documented in the Americas, leading to the assumption that PA, supposedly of oral origin, particularly surfaced in written language in contexts where normalization was less present (writers who only became writers out of necessity; see Oesterreicher, 2012).

In Portuguese, por completo might be a calque from Spanish:

por completo [Houaiss is underlying], hoje inteiramente integrado à língua portuguesa viva, foi dado como um espanholismo por alguns puristas, que sugeriram em seu lugar completamente, integralmente, de todo etc. [por completo, now fully integrated into the living Portuguese language, was considered a Hispanism by some purists, who suggested instead completamente, integralmente, de todo etc.] (Houaiss et al., 2015: s.v. completo).

This suggests that the Pt. PA por completo, according to these purists, did not evolve in Portuguese based on or inspired by pre-existing completo or completamente. This might be backed up by its rather late first attestation in CdP, which comes only from the 19th century (when the PA pattern in general was not that productive anymore).

As to why the preposition por was the one to be chosen (specifically in Spanish if we consider Pt. por completo as a later calque from Spanish), we can only make an educated guess. First, another PA, Sp. por entero ‘entirely’, which is documented since the 14th century (see next section), could have been a ‘model’ for creating por completo. Second – if we assume that the prepositions used to form PA-adverbials add a specific semantic value –, Sp. por as a continuer form of two Latin prepositions pro ‘for’ and per ‘through’, which merges the semantics of its Latin predecessors/etymons, would then convey some additional semantic value or cue underlining the process related and telicity related character of completo (and entero), whereas prepositions like de ‘from, by, of’ or cum ‘with’ would make less sense for this specific semantics. Other prepositions such as ad ‘to, at’ > Sp./Pt. a ‘to, at’, a poly-use preposition in Ibero-Romance, semantically also have the potential to convey process-related and telic information. Indeed, some sporadic attestations of the variant Sp. al completo (preposition a + article el + completo), are documented:

| (11) | Pero importa más el ambiente, el clima, que el escenario en sí, que por mucho que trate de explicar un locutor, nunca estará narrado al completo. | (Spanish) |

| “But the atmosphere, the climate, is more important than the scenario itself, which, no matter how much a radio announcer tries to explain them, will never be fully narrated.” (CDH, 1986, José Javier Muñoz; César Gil: La Radio: Teoría y práctica) | ||

According to the data in CDH, the adverbial al completo is quite recent, it appears only in the late 20th century. Data from CORPES XXI shows that al completo is used predominantly in Spain. For Portuguese, there are no occurrences of *ao completo as a PA-adverbial in any section (historical or present-day) of CdP. In this paper, we leave this variant – which proves that the pattern is still punctually productive in Romance – aside and focus on the older form por completo.

2.4. Overall frequencies in diachrony

In this section, we present the overall picture of the adverbials under scrutiny in CDH and CdP.5 Table 1 shows the absolute number of tokens resulting from the search queries and the normalized/relative frequency (ocurrences per 1 million words) of Sp. por completo and completamente in the five periods pre-established by CDH: Medieval Spanish, Spanish of the Golden Age, 18th, 19th, and 20th century Spanish.

Table 1: Spanish por completo and completamente (CDH), normalized frequency rounded to two decimals

| Period | Sp. por completo | Sp. completamente | |||

| Absolute frequency | Normalized frequency | Absolute frequency | Normalized frequency | ||

| 1064–1500 | Medieval Spanish | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0,08 |

| 1501–1700 | Golden Age | 2 | 0,02 | 5 | 0,05 |

| 1701–1800 | 18th century | 7 | 0,43 | 99 | 6,20 |

| 1801–1900 | 19th century | 1675 | 37,82 | 3367 | 76,02 |

| 1901–2005 | 20th century | 5455 | 30,87 | 9693 | 54,86 |

The first documentation of completamente is <completamiente> in 1408. The first documentation of por completo is from 1645. During the first centuries, both cognates are scarcely attested and only a few examples can be found. From the 17th century on, both adverbials’ frequency increases remarkably, especially that of completamente, which is clearly the more frequent cognate of both. This matches the general panorama of mente being preferred over PA from the 17th century onwards (see 2.3).

In Portuguese, both adverbials are documented later. Rather than reflecting an indeed later apparition of these adverbials, this could also be an effect of corpus size (remember that CDH is a much larger corpus than the historical part of CdP). Table 2 shows the absolute number of tokens and the normalized/relative frequency (cases per 1 million words, manually calculated) of Pt. por completo and completamente across the three centuries for which there are attestations in CdP.

Table 2: Portuguese por completo and completamente (CdP), normalized frequency rounded to two decimals

| Period | Pt. por completo | Pt. completamente | ||

| Absolute frequency | Normalized frequency | Absolute frequency | Normalized frequency | |

| 18th century | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1,34 |

| 19th century | 22 | 2,20 | 757 | 75,63 |

| 20th century | 292 | 14,60 | 1381 | 69,05 |

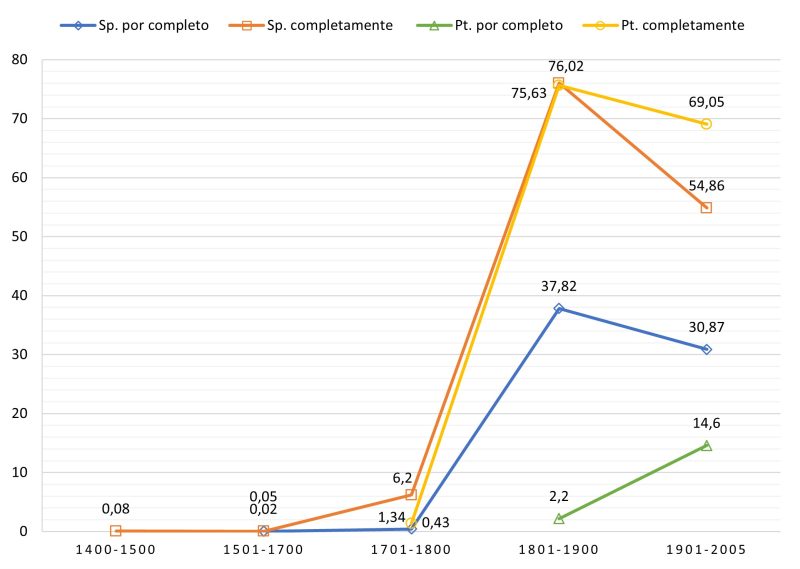

To compare both languages, Figure 1 combines the data (normalized frequency per 1 Mio words) from Tables 1 and 2, starting with the 15th century.

Figure 1: Normalized frequency (per 1 Mio words) of Spanish and Portuguese por completo and completamente

Despite of Sp. completamente being used since 1408, its relative frequency only starts to rise (very steeply) in the 19th century. This is an eye-striking parallel with Pt. completamente, which even only appears for the first time in the 18th century in CdP (see the yellow and the orange graph). Sp. por completo is also documented since the 17th century, but it is always less frequent than completamente. However, Sp. por completo equally shows a clear rise in frequency in the 19th century. The least frequent, and the latest adverbial of this group to enter the stage, is Pt. por completo, the supposed calque from Spanish, whose frequency increases from the 19th to the 20th century when the other adverbials show a slight decrease in frequency.

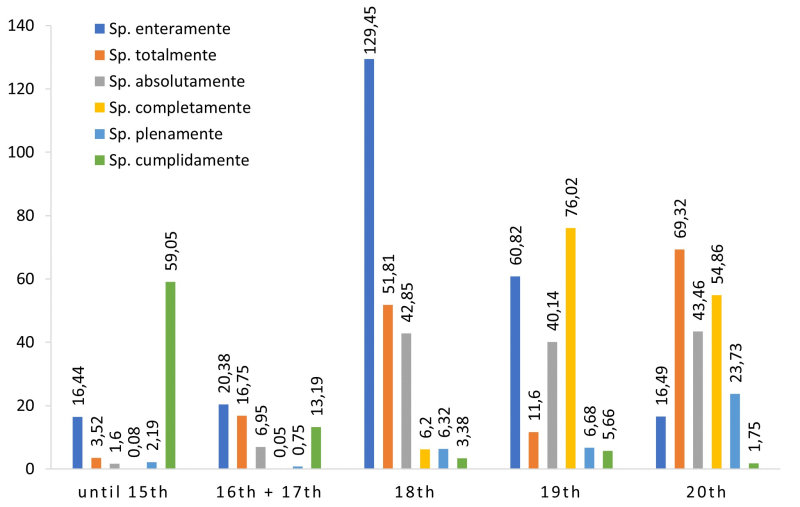

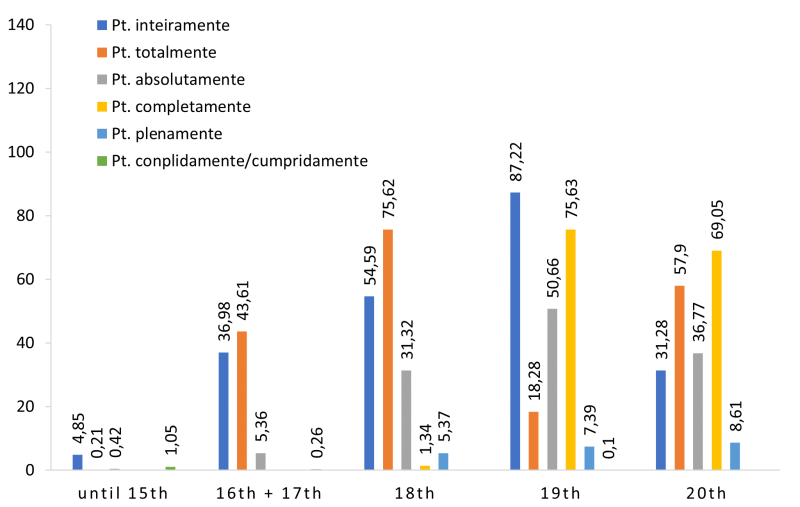

In Figures 2 and 3 we check if the rise in frequency of Sp./Pt. completamente in the 19th century is an exception or a common phenomenon within the paradigm of aspectual/degree adverbs. We compare the normalized frequencies of several adverbs – all (near-)synonymous with completamente and also cognates in Spanish and Portuguese – across the five periods established in CDH (again, manually calculating the normalized frequency for Portuguese in these periods in CdP).

Figure 2: Normalized frequencies (per 1 Mio words) of the Spanish paradigm of aspectual/degree quantifiers in CDH

Figure 3: Normalized frequencies (per 1 Mio words) of the Portuguese paradigm of aspectual/degree quantifiers in CdP

The rise of Sp./Pt. completamente in the 19th century is a quite ‘late’ fashion, since enteramente/inteiramente ‘entirely’, totalmente ‘totally’ (with a striking ‘gap’ in the 19th century), and absolutamente ‘absolutely’ already increased in frequency from the 16th or 17th century onwards. In the 20th century, completamente has become the most frequent member of this paradigm in Portuguese and the second most frequent in Spanish. Therefore, completamente – to a certain degree – replaces the other adverbs.

The general rise of frequency of the adverbs in Figures 2 and 3 may also coincide with the documentation of more diverse text types in the corpora; the percentage of literary, poetic, and descriptive (scientific) texts increases enormously with progressing time. As a hypothesis, these are supposedly texts in which more adverbs are used, and in which also a certain ‘need’ of degree quantifiers might be felt (while in legal documents, the predominant text type of the surviving documents from the Ibero-Romance Middle Ages, adverbs are rather scarce: it suffices to check, e.g., the legal documents from 912 to 1300 published by Ruiz Asencio and Ruiz Albi, 2007, to get a first impression).

Contrarily to the -mente-paradigm, the corresponding PA-paradigm is more reduced, and its exponents are less frequent, but just as with completamente, por completo is not the first adverb(ial) of its kind in its paradigm. Sp. por entero ‘entirely’ is documented earlier (first attestation in 1300, Sp. por completo in 1645), and Pt. por inteiro ‘entirely’ is first documented in the 16th century (once, as per inteiro), while Pt. por completo only appears for the first time in the 19th century.

As shown in Table 3, Sp./Pt. por entero/inteiro is used more frequently than Sp./Pt. por completo in earlier centuries, but then is outpaced by the it – just as Sp./Pt. enteramente/inteiramente by Sp./Pt. completamente.

Table 3: Normalized frequency of Spanish and Portuguese por completo and por entero/inteiro (CDH/CdP)

| Sp. por entero | Sp. por completo | Pt. por inteiro | Pt. por completo | |

| 1064–1500 | 3,70 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1501–1700 | 8,49 | 0,02 | 2,30 | 0 |

| 1701–1800 | 6,39 | 0,43 | 0 | 0 |

| 1801–1900 | 5,59 | 37,82 | 2,50 | 2,20 |

| 1901–2005 | 4,79 | 30,87 | 4,28 | 14,60 |

Other PAs of this paradigm, such as Sp. en extremo ‘extremely’ (1400), en absoluto ‘absolutely’ (1549; again, the supposed first attestation in CDH from 1489 stems also from Gaspar y Remiro’s translation realized between 1898 and 1910 of an 15th century Arabic text), Sp. de pleno ‘completely’ (1504) and Sp. en total ‘totally’ (1575) are all first attested earlier than Sp. por completo (1645). In Portuguese, two of the existing corresponding PAs are documented first in the 16th century: em cheio and ao extremo/em extremo. The adverbial em absoluto is attested first in the 19th century, just as no total (all dates according to CdP), which confirms that 19th century por completo is, indeed, together with the two latter examples, a ‘late’ member of this paradigm. A simple quantitative comparison of these forms is not possible, though, because there are a lot of interfering examples in the corpora in which these sequences are not interpretable as adverbials (a manual filtering is not feasible within the limits of this article).

3. Steps in the semantic and syntactic evolution of completamente and por completo

In this section, we will first focus on por completo in Spanish (3.1) and Portuguese (3.2), and then contrast its evolution with completamente in Spanish (3.3) and Portuguese (3.4).

3.1. Semantic-functional evolution of Sp. por completo

The first authentic attestation of por completo from 1645 is a post-posed aspectual quantifier modifying a verb:

| (12) | Se van enriqueciendo los religiosos de esta América con las limosnas, fundaciones, rentas, comercio y opulentísimos negocios, y entretanto los diezmos concedidos por la Santa Sede a nuestros católicos príncipes y por ellos con su esclarecida y regia piedad aplicados a las catedrales para su mantenimiento se consumen con tales lucros y desaparecen por completo. | (Spanish) |

| “The clerics of this very America are getting richer with alms, foundations, rents, commerce and opulent business, and in the meantime the tithes granted by the Holy See to our Catholic princes and by them with their enlightened and royal piety applied to the cathedrals for their maintenance are consumed with such wastefulness and disappear completely.” (CDH, 1645, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza: «Carta a Inocencio X» (Cartas), Testimonios varios [México]) | ||

In this example, the verb desaparecer ‘to disappear’ itself is clearly telic and process-related, allowing to interpret por completo basically only as an aspectual quantifier (original source meaning): the process of disappearing is fully completed when no money at all is left.

The next stage in the evolution of por completo, documented a century later, consists of the foregrounding of the degree-quantification-reading, both when por completo modifies a verb (desconocer por completo) or an adjective (inútil por completo). In both instances, por completo is still in post-position (see example 13).

| (13) |

No dudo que tendrá algunas cualidades, como ordinariamente las tienen los árboles y plantas que se crían en semejantes lugares; he de confesar que las desconozco por completo, ni he oido entre los naturales cosa particular que sea digna de apuntarse. […] La yerba llamada lunga-lunga es muy parecida á la del ajonjolí con la diferencia de ser ésta buena y utilísima, y la otra inútil por completo: no hemos de poner los ojos solamente en lo exterior, para conocer lo bueno ó lo malo, sino en los frutos que cada uno lleva […] |

(Spanish) |

| “I do not doubt that it will have some qualities, as the trees and plants that grow in such places usually have; I must confess that I am completely unaware of them, nor have I heard anything particular among the natives that is worth noting. […] The herb called lunga-lunga is very similar to sesame, with the difference that latter is good and very useful, and the former is completely useless: we must not look only at the exterior, to know the good or the bad, but at the fruits that each one bears [...].” (CDH, c1754, Juan José Delgado: Historia general sacro-profana, política y natural de las islas del Poniente llamadas Filipinas) | ||

In example (13), por completo is a degree quantifier of the verb desconocer ‘to not know’ and the adjective inútil ‘useless’. The verb desconocer is atelic and durative. Therefore, desconocer por completo can only be read as a context of degree modification. Por completo does therefore not designate the maximum limit or endpoint of a telic process, but rather the maximum (or at least a very high) degree of the properties or the states expressed by the semantics of the corresponding verb.

The adjective inútil ‘useless’ could, in principle, also refer to the result of a telic process (of getting useless), and an aspectual reading of por completo would indicate that the culmination of this telic process is reached (see also completamente rojo and the discussion in 1.1). However, in this specific context referring to a plant that did not undergo such a process, the foregrounded interpretation is that of degree quantification, indicating the highest possible degree of uselessness (obviously, subject to definition): the absolute maximum, a 100% of uselessness (or, 0% of usefulness). Since the aspectual interpretation is ruled out in both instances in (13), the example illustrates two switch or isolating contexts.

The first attestation of por completo modifying a participle is from 1856 (coinciding with the steep rise in frequency of por completo in the 19th century; see 2.4). In this example, the PA is still post-posed and is ambiguous (aspectual and degree quantifier), caused by the static semantics of estar. This is a classic bridging or critical context.

| (14) | Deberíamos á continuacion de la descripcion y discusion teórica de los aparatos que se han puestos en práctica para la aplicacion del aire caliente; pero teniendo este elemento únicamente aplicacion en la reduccion de los minerales de hierro, y estando por otra parte abandonada esta práctica casi por completo, nos ocuparemos del estudio de esta modificacion del aire al tratar del hierro. | (Spanish) |

| “We should continue with the description and theoretical discussion of the apparatuses that have been put into practice for the application of hot air; but this element having only application in the reduction of iron ores, and this practice being moreover almost completely abandoned, we will deal with the study of this modification of air when dealing with iron.” (CDH, 1856, Constantino Sáez de Montoya: Tratado teórico práctico de metalurgia. Dispuesto para uso de las escuelas y establecimientos en donde se enseñe esta asignatura, para los metalurgistas, mineros, etc.) | ||

Since abandonada ‘abandoned’ is a participle, it has both verbal and adjectival properties: it retains a verbal reading (abandonar por completo ‘to abandon completely’ > abandonada por completo ‘completely abandoned’), while being a nominal. Furthermore, the past participle form adds a perfective factor to the mix, i.e. the action of abandoning is concluded (i.e., the condition of a 100% of abandonment is met, since no one uses the described technique anymore). Por completo is, thus, also ambiguous between verb-modification and adjective-modification, but maintains the prototypical position of verb-modifiers in Ibero-Romance (post-position).

Still in the mid-19th century, a new syntactic position is documented: por completo as a degree quantifier is also pre-posed to participles and adjectives, that is, it takes the prototypical position of other types of degree quantifiers (such as mente) when modifying adjectives. The first attestation of such pre-posed por completo modifying a participle (cubierto ‘covered’) comes from 1865 and is the first documentation of pre-position of por completo at all (example 15):

| (15) | Así, valuada esta última en 5.100,000 miriámetros cuadrados, 3.700,000, algo ménos de sus 3/4 están ocupados por las aguas, y comparadas las superficies de ambos hemisferios, el boreal contiene él solo 4/5 de tierra, mientras que el austral, casi por completo cubierto de agua, 1/5. | (Spanish) |

| “Thus, the latter being valued at 5,100,000 square myriameters, 3,700,000, slightly less than 3/4 are occupied by water, and comparing the surfaces of the two hemispheres, the boreal alone contains 4/5 of land, while the austral, almost entirely covered with water, 1/5.” (CDH, 1865, Manuel Merelo: Nociones de geografía descriptiva) | ||

Example (15) is again functionally ambiguous: casi por completo cubierto ‘almost completely covered’ can still be interpreted as the result of successively covering the landscape with water (aspectual reading), but it can also be interpreted as an example of high degree quantification (i.e., this is also a bridging/critical context). Again, the use of the resultative passive with the verb estar may even foreground the aspectual reading.

So, it is not a degree-quantifier-reading alone that can trigger pre-position. Moreover, examples (13) to (15) show that the semantic interpretation of por completo depends on the semantics of the modified element and on the context, but not so much on its syntactic position. Nevertheless, examples of pre-posed aspectual or ambiguous por completo possibly paved the way for pre-position of degree quantifying por completo. Indeed, por completo in pre-position modifying ‘regular’ adjectives is documented at just about the same time in the 19th century, as it is with verbal adjectives (participles):

| (16) | Estas son por completo distintas al pié de fábrica, de las que despues se fijan para el servicio; pues sabido es que los proyectiles, como todos los objetos elaborados por la mano del hombre, sufren más ó ménos con el uso y con los demás accidentes á que están expuestos, […] Al abandonar el proyectil la pieza, el anillo de papier maché se deforma y desaparece de una manera por completo inofensiva. | (Spanish) |

| “These [established tolerances] are completely different when [the projectiles are] fresh from the factory than those that are later fixed for service; for it is known that the projectiles, like all objects made by the hand of man, suffer more or less with use and with the other incidents to which they are exposed, [...] When the projectile leaves the cartridge, the ring made of papier mâché is deformed and disappears in a completely harmless manner.” (CDH, 1870, Cándido Barrios: Nociones de Artillería, I) | ||

| (17) | Siendo, pues, nuestro dogma el desarrollo de la personalidad humana, es necesario que coloquemos al hombre fuera de todo daño, como el cristianismo coloca sus dogmas fuera de la discusion. Si alguna vez la humanidad llega á arrancarse de su corazon el pecado, á penetrar con su mirada en lo más profundo del seno del sér, entonces nuestra religion habrá caducado y el precepto humano será por completo positivo. | (Spanish) |

| “Since our dogma is the development of the human personality, it is necessary that we place man out of harm’s way, as Christianity places its dogmas out of discussion. If humanity ever manages to tear sin from its heart, to penetrate with its gaze into the profoundest depths of the bosom of existence, then our religion will have expired and the human precept will be entirely positive.” (CDH, 1873, Serafín Álvarez: El Credo de una Religión Nueva) | ||

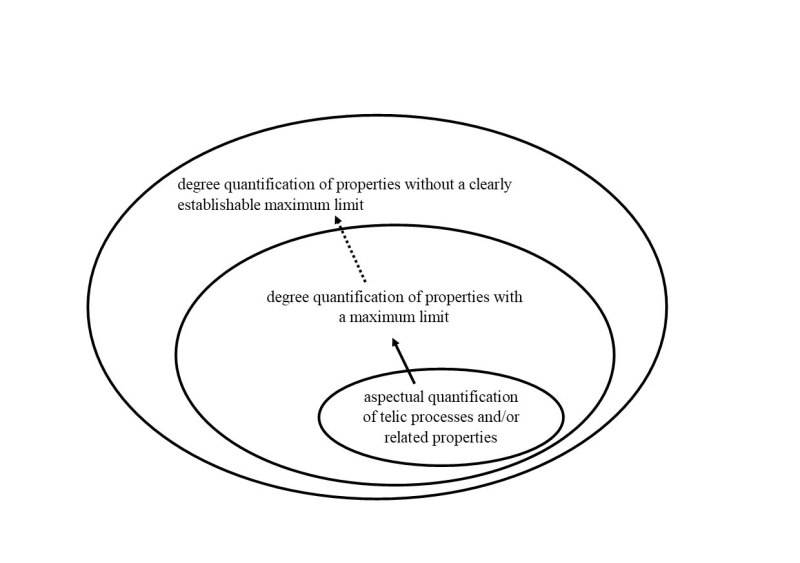

In (16‑17), the original reading (aspectual quantification) is ruled out, i.e., these examples represent switch or isolating contexts. The only likely interpretation of por completo distinta, por completo inofensiva (16) and por completo positivo (17) is that of a degree quantifier, since the semantics of these adjectives is not linked to telicity, and they do not denote process-induced properties. But all three adjectives, distinto, inofensivo, and positivo, denote scalar properties that can be somewhat objectively limited by por completo, i.e., there is a 100% maximum degree of distinction, inoffensiveness, and positivity that cannot be surpassed. We will call this semantic trait ‘maximum limit’ or max.lim.

This max.lim can be a trait of telic verbs (Sp. cambiar ‘change’, Pt. mudar ‘change’), adjectives (and particularly past participles) linked with telicity (denoting the result of a telic process, like Sp./Pt. cambiado/mudado or the Sp./Pt. adjective completo itself) and ‘atelic’ adjectives (like Sp./Pt. distinto, inofensivo, positivo) alike.

The semantic property of por completo and completamente of denoting or foregrounding such a maximum limit will be called ‘designate maximum limit’, or des.max.lim.

Such a maximum limit is, probably, not inherent in the core semantics of distinto, inofensivo, and positivo, as it is a question of definition. It is only established and attributed by por completo, subjectively, according to the speaker’s definition or idea of maximum distinctness, inoffensiveness, or positiveness. Since in telic, process-related contexts, a maximum of execution of an action or an event is reached in the end (the potential for this represented by the semantic trait max.lim), and por completo exactly foregrounds this maximum completion of such a telic action or event (e.g., llenar por completo ‘to completely fill up to a 100%’), one can argue that por completo is destined to carry over this semantic component or trait of designating this maximum (des.max.lim) to its degree quantifying function. It is this trait which makes the transition to being a degree quantifier of certain scalar adjectives much easier. Contrarily, the semantic trait that gets lost in the evolution from aspectual to degree quantification is that of reaching the maximum as the result of a telic, process-related event. Therefore, por completo expands the semantic-pragmatic contexts it can appear in as the result of a semantic generalization.

3.2. Semantic-functional evolution of Pt. por completo

Pt. por completo appears for the first time in the 19th century in CdP.6 It is documented as an aspectual quantifier placed after the verb destruir ‘to destroy’ (i.e., the process of destroying is completed until absolutely everything is 100% destroyed):

| (18) | [...] apesar de ter a polícia corrido para evitar qualquer assalto a esses jornais, não chegou a tempo de evitá-lo, pois a multidão aos gritos de viva a República e à memória de Floriano Peixoto invadiu aqueles estabelecimentos e destruiu-os por completo, queimando tudo. | (Portuguese) |

| “[...] although the police rushed to prevent any assault on these newspapers, they were not in time to prevent it, because the crowd shouting “long live the Republic” and “to the memory of Floriano Peixoto” invaded these establishments and completely destroyed them, burning everything to the ground.” (CdP, 19th century, Euclides da Cunha: Os Sertões) | ||

In the same century (and by the same author) por completo is also used as a post-posed modifier of the participle refeitas (‘redone’), with a clear aspectual-quantifier-reading, too:

| (19) | Duvido mesmo já que os aficionados do Campo Pequeno, pela maioria exigentes e sabedores da técnica taurina, se achem dispostos a tolerar espectáculos só com portugueses, e viverá pouco quem não chegar a ver daquele redondel não só expungidos os maus artistas, como também ampliadas e refeitas por completo as corridas de touros, que entre nós são ainda um espectáculo branco e sem catástrofes. | (Portuguese) |

| “I really doubt that the aficionados of Campo Pequeno, the majority of whom are demanding and knowledgeable about bullfighting techniques, will be willing to tolerate shows with only Portuguese performers, and it will be a short life for anyone who doesn’t get to see not only how the bad artists are expelled from that ring, but also how the bullfights, which here are still a clean spectacle without catastrophes, are expanded and completely redone.” (CdP, 19th century, Fialho de Almeida: Gatos 6) | ||

One century later, in the 20th century, por completo is also documented post-posed to adjectives. In example (20), it modifies the adjective alheia ‘alien’:

| (20) | Com uma resignação de freira, alheia por completo ao mundo, vivendo na perpétua lembrança do marido, na exclusiva preocupação dos filhos, passou anos Eugênia sem sair de casa, levando uma vida toda crepuscular, na inteira abdicação do seu querer, colada ao dever como a lapa ao rochedo, alumiada e forte sempre a alma do alimento ázimo do Passado, o seu fino rosto austero idealizado por uma transcendente, uma inabalável expressão de confiança e de doçura. | (Portuguese) |

| “With the resignation of a nun, completely oblivious to the world, living in perpetual remembrance of her husband and in exclusive concern for her children, Eugenia spent years without leaving the house, living an entirely crepuscular life, in complete abdication of her needs, glued to her duty like a limpet to a rock, her soul always illuminated and strong from her unleavened feeding on the past, her thin austere face idealized by a transcendent, unshakeable expression of trust and gentleness.” (CdP, 20th century, Abel Botelho: A Consoada) | ||

The context of this example could be classified as a bridging/critical context: in principle, alheia por completo ‘completely oblivious/alien’ is ambiguous between aspectual or degree quantification. However, although this characteristic could be the result of a gradual process of becoming oblivious, it seems that the degree quantifying reading is foregrounded in (20).

In the same century, por completo appears as well in a new syntactic position; it is pre-posed to a participle for the first time:

| (21) | Ora a Conceição morava ali bem perto, quáse à raiz da rua da Atalaia, em casa da conhecida Consuelo, a Consuelo rebolona, antiga dançarina de S. Carlos, agora quáse por completo passada à inactividade, apenas tendo, por pausas, alguma escritura ocasional em teatros de #3.a ordem. | (Portuguese) |

| “Now, Conceição lived very close by, almost at the beginning of Rua da Atalaia, in the house of the well-known Consuelo, Consuelo the show-off, former dancer at S. Carlos, now almost completely inactive, with only occasional assignments in 3rd order theaters.” (CdP, 1957, Fernanda Botelho: O Angulo Raso) | ||

Example (21) is clearly aspectual: the process of ceasing professional activities extends over time and has almost completely culminated (the maximum limit will be reached with a 100% inactiveness).

Finally, pre-posed modification of adjectives is only attested in the 21st century, like in the following example of modification of alheia ‘alien’ (22):

| (22) | Esta noção de uma igreja universal invisível é por completo alheia do Novo Testamento. | (Portuguese) |

| “This notion of an invisible universal church is completely alien to the New Testament.” (CdP Web/Dialects, Brasil, internet) | ||

In this specific context, the copula verb é ‘is’ presents a state and excludes a telic, process-related reading of é por completo alheia. Therefore, in contrast to example (20) above, an aspectual reading is completely ruled out in (22), and the reading of por completo as a maximum degree quantifier is the only possible interpretation. It is, therefore, clearly a switch/isolating context. In this context, again, the modified adjective has the semantic trait max.lim: por completo (via its des.max.lim trait) establishes that the maximum possible degree of alienness is intended (100%). Moreover, examples (20) and (22) show that not only the specific semantics (max.lim or not, telicity related or not) of the modified element (in 20 and 22, the adjective alheia) determines the interpretation of the quantifier por completo, but it is also the specific broader context of the sentence which does.

To sum up, Pt. por completo roughly goes through the same stages as already documented for Sp. por completo, from verb modification via participle modification to adjective modification (in Spanish, though, participle and adjective modification both first appear nearly at the same time, within five years), and from pre-position to post-position, but remarkably later.

3.3. Semantic-functional evolution of Sp. completamente

The first attestation of Sp. completamente shows that this adverb is used first as a verb quantifier in the early 15th century:

| (23) | Porque vos mando á todos é á cada uno de vos en [vuestros] logares é jurisdicciones, que veades estas mis Leyes, ó el [dicho] su traslado signado, como [dicho] es, é publicadlas é facedlas guardar é complir las cosas en ellas contenidas en todo é por todo, bien é completamiente, segun que en ellas se contiene, é no vaiades, ni pasedes, ni consintades ir ni pasar contra ellas, ni contra parte dellas, agora ni de aqui adelante, en ningun tiempo, por alguna razon que sea […] | (Spanish) |

| “For I command you all and each one of you in [your] homesteads and jurisdictions, that you see these my Laws, or the [said] signed copy of them, as it is [said], and publish them and make them respected and make that the things that are contained in them are well and completely fulfilled from top to bottom, according to what is contained in them, and do not go against them, nor trespass them, nor consent anyone to go them or trespass them, nor any part of them, now or hereafter, at any time, for any reason whatsoever […]” (CDH, 1408, Anónimo: «Ordenamiento hecho por la reina gobernadora doña Catalina, a nombre de su hijo el señor don Juan II, sobre la divisa y traje de los moros») | ||

In example (23), completamente modifies the verb cumplir ‘comply with, lit. fulfill’ and refers, in this context, to obey the content of laws in the maximum degree possible, i.e., in every single detail. While English to comply with is arguably not telic, Spanish cumplir, in other contexts than in (23), could still have a rest of a telic, process-related semantics (remember that the verb cumplir and the adjective completo go back to the same Latin etymon, see 2.1; hence, cumplir completamente is almost a tautology). But the semantics ‘fulfill’ still is rather punctual than telic, so also Spanish cumplir must be interpreted primarily as non-telic. Therefore, the more probable interpretation of completamente in example (23) is that of a degree quantifier (i.e., already a switch/isolating context). This would mean, assuming a development according to the Heine’s (2002) and Diewald’s (2002) stages, that the supposedly pre-dating bridging/critical context had occurred probably very early, and, in any case, it is not documented in CDH.

As a next step, completamente appears as a pre-posed degree modifier, first attested in the mid-15th century, modifying the verb consentir ‘to consent’ (example 24).

| (24) | En lo qual ella llagada de un muy estranno dolor, la fama de sus virtudes en esto seer manzillada, la qual ella tenia speçial entre todas las duennas romanas, que esto escogiesse non sabia, a la fin, aunque non completamente, consintio con Sexto Tarquino soliçitador de adulterio. | (Spanish) |

| “In it [i.e., the adultery], she, struck by a very strange pain, as the fame of her virtues, [a fame] which she had in a particular way among the Roman women, was tainted, didn’t know that she chose this [i.e., the adultery], [and] in the end, even if not completely, consented with Sextus Tarquinius, the requester of the adultery” (CDH, 1440–1455, El Tostado [Alonso Fernández de Madrigal], Libro de amor e amicicia) | ||

While consentir certainly can be considered as having the max.lim trait (again, as almost always in such cases, subject to subjective definition by the speaker), it would be difficult to attest it a telic character, which results in the near impossibility to read (24) as an instance of aspectual quantification and makes an interpretation as degree quantification the only reasonable choice (switch/isolating context).

Sp. completamente as a pre-posed modifier of adjectives appears as early as the first half of the 17th century, more than two centuries earlier than Sp. por completo:

| (25) | y así es que todo suceso importante ocurrido dentro ó fuera de España, era al punto narrado y glosado por mil plumas desconocidas, mas ó menos autorizadas, que se disputaban á porfía el derecho de anunciar al público leyente noticias las mas veces poco exactas, siempre exageradas, cuando no completamente falsas. | (Spanish) |

| “And so it is that every important event which occurred inside or outside Spain, was at once told and commented on by a thousand unknown pens, more or less authorized, who were eagerly vying for the right to announce to the reading public most often inaccurate, always exaggerated, if not completely false news.” (CDH, 1634, Sebastián González: «Carta», Cartas de algunos padres de la Compañía de Jesús, I) | ||

| (26) | Los que niegan la possibilidad de la transmutación de los metales ponen mucho ahínco en probar que son de especies completamente distintas y que, assí, es impossible el tránsito de unos a otros; | (Spanish) |

| “Those who deny the possibility of the transmutation of metals put much effort into proving that they are of completely different kinds and that, therefore, the transition of one into the other is impossible;” (CDH, 1640, Álvaro Alonso Barba: Arte de los metales) | ||

In principle, both completamente falsa and completamente distinta could be the results of telic processes, but in the specific contexts of examples (25) and (26), the aspectual reading is excluded: both falsas ‘false’ and distintas ‘different’ describe stable characteristics of certain news (25) and certain metals (26). The adverb completamente expresses the maximum degree (100%) of these characteristics (i.e., there is nothing correct or similar at all). Therefore, both examples are also illustrative of the switch/isolating context in which the atelic maximum degree interpretation is the only possible one.

It is noteworthy that in its first documentation in which it is not modifying a verb, completamente immediately appears as a pre-posed modifier of adjectives. Only a few cases of modification of participles are documented in the early phase, the first attestation (ex. 27; 1680) dates from some decades later than the first attestations of modification of adjectives (ex. 25; 1634, and ex. 26; 1640). In (27), the interpretation of completamente as a maximum degree quantifier is foregrounded, since desordenado ‘in disorder’, in this specific context, is not presented as the result of a process. This may be underpinned by the combination with the Sp. copula ser, although at this rather early stage, ser still could be used in resultative and ‘static’ contexts, for permanent and temporary states, as the distinction ser vs. estar hadn’t yet been fully cemented (exemplified, e.g., by Penny, 2002: 160).

| (27) | No solamente nos es permitido cambiar lo antiguo, sino rechazarlo totalmente cuando es completamente desordenado | (Spanish) |

| “We are not only allowed to change the old, but to totally reject it when it is completely in disorder.” (CDH, 1680, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora: Teatro de virtudes políticas que constituyen a un príncipe) | ||

The pattern “participle + post-posed completamente” occurs even later, in the first half of the 18th century:

| (28) | Calificado, ya a mi parecer, con esta ejecutoria, el esplendor de mis ascendientes, y refutada la malignidad de mis contrarios, lo primero con la ejecutoria que expongo, y lo segundo, con la relación que llevo hecha de mis procederes, no me queda duda en que Vd. y sus amigos en quien reina una razón desapasionada y un juicio prudente y cristiano, nieguen sus oídos a las perversas calumnias de mis opuestos, desvanecidas y deshechas completamente en virtud de las poderosas razones que manifiesto. | (Spanish) |

| “Having proven, in my opinion, with this patent of nobility, the splendor of my ancestors, and having refuted the malignity of my opponents, the first with the patent of nobility which I hereby show, and the second with the account I have given of my actions, I have no doubt that you and your friends in whom dispassionate reason and prudent and Christian judgment reign, will refuse to listen to the perverse calumnies of my opponents, which are completely vanished and undone by virtue of the powerful reasoning I am presenting.” (CDH, 1737, Juan Francisco Melcón: Carta satisfactoria) | ||

In (28), completamente modifies, arguably, either one (deshechas ‘undone’) or two participles (desvanecidas y deshechas ‘vanished and undone’), which stem from telic, process-related verbs. In this context, completamente is interpretable as an aspectual quantifier: the culmination of the process of vanishing and undoing the denounced calumnies is reached by presenting several arguments. Even if we interpret this, undoing and vanishing, as rather quick, punctual events in other contexts, telicity is still inherent, the duration of the inherent process does not necessarily play a role in acknowledging the principal existence of this telic process.

On the one hand, the equally (compared with por completo) late attestation of completamente as a post-posed aspectual quantifier of participles can maybe be attributed to the arbitrariness of the historical data (lack of documentation). On the other hand, the existing data suggests that completamente and por completo start to modify participles only comparably late (which is difficult to believe, though, considering the verbal character of participles, and the fact that all four Sp./Pt. adverbial cognates studied in this paper first appear with verbs). We will come back to this discussion in Section 4.1.

3.4. Semantic-functional evolution of Pt. completamente

In Portuguese, completamente first enters the scene in the 18th century, as an aspectual quantifier placed after the verb it modifies (restablecer ‘restore’, a verb that is clearly process-related and telic):

| (29) | Declarando-se Hipócrates a Fila e persuadindo-a a lisonjear o amor e esperanças do príncipe, conseguiu restabelecer-lhe completamente a saúde. | (Portuguese) |

| “By declaring himself to Fila and persuading her to flatter the prince’s love and hopes, Hippocrates managed to restore her health completely.” (CdP 1756, Cavaleiro de Oliveira: Cartas) | ||

The modification of adjectives, with completamente both post-posed and pre-posed, follows in the 19th century:

| (30) | Ela disse à sua aia: - “Phebe, eu estou só com Carlos; e quero estar só. Em casa para ninguém.” – “Sim, minha senhora.” Resposta obrigada do criado inglês a tudo. E ficámos sós completamente. | (Portuguese) |

| “She said to her maid: ‘Phebe, I’m alone with Carlos, and I want to be alone. I am at home for no one.’ – ‘Yes, madam.’ The English servant's obliging reply to everything. And we remained completely alone.” (CdP, 19th century, Almeida Garrett: Viagens) | ||

| (31) | Homem de quarenta e sete anos de idade, baixo e aparentemente robusto, feições regulares, tez moreno-escura, olhos negros e vivos, tinha larga testa e belo crânio, completamente calvo, que dos paraguaios lhe valeu injuriosa alcunha. | (Portuguese) |

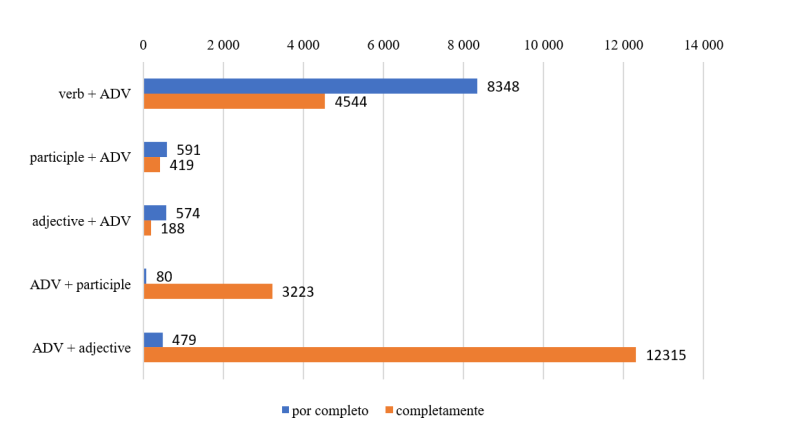

| “He was a man of forty-seven years, short and apparently robust, with regular features, a dark brown complexion, lively black eyes, a broad forehead and a beautiful skull, completely bald, which earned him an insulting nickname from the Paraguayans.” (CdP, 19th century, Afonso de E. Taunay: A Retirada da Laguna) | ||