The production of Antony and Cleopatra staged by Pascal Rambert in 1995 left strong memories in my mind. The play was performed in a National venue, MC93 Bobigny, situated in the northern suburbs of Paris, where the choice of plays is always challenging (needless to say, attracting educated Parisians rather than the multi-cultural locals); the actors playing the title‑parts, André Marcon and Dominique Reymond, had a long‑standing reputation as major actors, the young director, Pascal Rambert, was already well‑established as one of the leaders of his generation.

However, little did I know that the search for documents would be so full of difficulties and reveal such dramas.

When I started my research, I was told at the MC93-Bobigny Theatre that the storage-rooms had just been flooded destroying all their archives;1 Pascal Rambert’s agent answered my email straight away saying he had no archives on this production;2 André Marcon wrote to me he “would prefer not to” talk about this part as he felt that it was not a successful production and it would bring back heavy memories;3 the archives of the National Library were particularly thin, there were hardly any documents or reviews on the production. In his article, “Nightwatch Constables and Domineering Pedants: the past, present and future of Shakespearean theatre reviewing”, Paul Prescott seems to assume that getting material will be made easier in the modern world: “Theatre historians of the future wishing to reconstruct a production in 2012 will—in theory at least—only have to contact a company or a theatre archive to access a range of materials”, because “theatre companies are now generating an exponentially increasing amount of archivable materials by themselves” (Prescott 29). Note the “only have to” in this optimistic statement which did not prove true in this particular case, indeed reality may resist theory. However, I must say that this lack of archival memory and these closed doors only whetted my curiosity and encouraged me to inquire further.

The première of the production was supposed to take place on 12 January, according to the date printed on the programme, but it turned out that it was in fact postponed for a few days, to 18 January.4 It is a very unusual case, especially on a National stage. It showed that the time of rehearsal might not have been long enough to solve all the practical questions, with probably some hitch(es) at the very last moment, serious enough to need a few extra days of work.5

In his memoirs, published in 2005, exactly ten years after the staging of Antony and Cleopatra, when Pascal Rambert had made a name for himself, he mentions that his early success had been too quick and overwhelming for him. He had been caught in a prolific but devastating whirlwind of creation “until the boomerang shot of Shakespeare, the failure of Antony and Cleopatra in 1995 when everything stops” (Rambert in Goumarre 13).6 A failure? According to the words of the director himself. In this text, Rambert alludes to a post‑traumatic effect as an artist, with a dark period on the verge of a mental break down.

This confusion could not be perceived for the one‑night audience members. Personally, I really thought that the production highlighted very well some of the main issues of the play. Fortunately, my research led me to the actress playing the part of Cleopatra, Dominique Reymond, who was kind enough to accept an interview and provided me with some direct information.7

This paper will explore and discuss some of the aesthetical stands taken by Rambert in his approach of the play: the attention to the words of the text and the rhythm of the scenic action, then his focus on the two lovers magnifying the love story in which Cleopatra takes the lead, and last the visual defeat of Antony at the battle of Actium with the actors having to play on a stage full of water.

I. Poetry over scenography

1. Slow time

As a reaction against the teaching of Antoine Vitez8 who kept advocating his trainees to amplify everything on stage (voice effects, gestures, movements …), Pascal Rambert decided to take the opposite stand and get away from a “deliberately excessive acting practice” belonging to a historical tradition which he did not feel he could fit in. So he, deliberately, endeavoured to “slow down everything, the delivery of the text, the movement, in order to increase something else, the time which must pass over the stage, the time the actors must spend on stage” (Pascal Rambert in Laurent Goumarre 20–21).9

This frontal opposition to Vitez’s teaching seems rather surprising as Vitez is especially remembered for having worked on a kind of suspended rhythm, “in order to allow the dramatic time to flow” (Vitez).10 However, Rambert further supports his argument on the grounds that he is after some presence on stage even when the actors do not have to deliver any cues, so, beyond the words themselves (Rambert in Goumarre 33).11 Rambert refers to two influential sources of inspiration. First, the famous German dancer Pina Bausch and her Company, Tanztheater, who explored a fable through modern dance modelled on everyday gestures, and who started to punctuate her later scenarios with some texts.12 He also refers to a theatre director, Claude Régy, who promoted a minimalist aesthetics in which some of the actors, immobile on a bare stage transformed by suggestive lighting effects, had to convey a feeling of scenic presence through the only means of their bodily attitude.13 Rambert thus claims that the actors “could play without moving, deliver a monologue, extend its duration, and this duration became theatre” (Rambert in Goumarre 18).14

However, Rambert’s stands were not favourably received for Antony and Cleopatra. One review, expecting sound and fury in a play devoted to a violent passion between the protagonists, an expectation which was conveyed by the programme featuring some incandescent lava (Figure 1), complained of a lack of direction in an article entitled “Shakespeare without passion”. The reviewer, René Solis, who obviously knew about the rehearsal difficulties (without naming them), could not find harsh enough words to describe “this absence of performance”: “the stage seems bare as [the actors] seem so far away from each other, condemned to a hieratic austerity, devoid of passion” (Solis 1995).15

Figure 1. – The programme of the performance.

With courtesy of the Archives of MC93 Bobigny.

Indeed, the two characters are far apart in the play. They long to be together but are not often united by Shakespeare, and more often than not, when they are, they are at odds with each other. Antony is also at odds within himself every time “a Roman thought” (1.1.88) crosses his mind or Roman affairs are in his way.16 He is alone, fighting with his passion that Philo qualifies as “dotage” (1.1.1) in the opening line of the play, and which he eventually acknowledges towards the end of act III (3.11.15). Then, he admits being completely under the irresistible charm of Cleopatra, his defeated opponent whom he names “my queen” (1.1.55), a contradictory conflation of a possessive and a title of superiority, who has caught him in her net of seduction and domination.

2. The Poetry of Shakespeare’s words

Shakespeare gives the sense of Cleopatra’s seductive power, not by a visual pageantry, but through the most inspired description of Enobarbus in act II (2.2.201–242). We can imagine the actor playing Enobarbus standing on the bare boards of the Jacobean stage to embark on the lavish description of the queen’s munificence as her barge slowly progresses towards the “Third Pillar of the World”, the victorious Roman General, now her master. His words exhale “a strange invisible perfume” which “hits the senses” (2.2.222) of Agrippa and Maecenas, Octavius Caesar’s followers, as they provide an approving audience within this dramatic mise en abyme and also of the audience without, of all times, who can also revel in the words and rhythm of this most beautiful passage, preceded by Agrippa and Maecenas’s enraptured comments, but who perceive immediately the danger of such a powerful seductress for Antony and for the Roman Empire (2.2.243).

By the same token, Rambert wanted the words to “o’erflow” (1.1.2) his production. Indeed, the text is a primordial component of his own work. As a writer and playwright in his own right, he provides a good sample of a style based on a nervous, vehement flow of words.17 Thus, Jean-François Peyret,18 a translator and a director, was commissioned to write a new version of the play which was praised in most reviews,19 and more importantly by Dominique Reymond who, as Cleopatra, was in the best position to appreciate its precise wording, its clarity, its easy flow of delivery.20

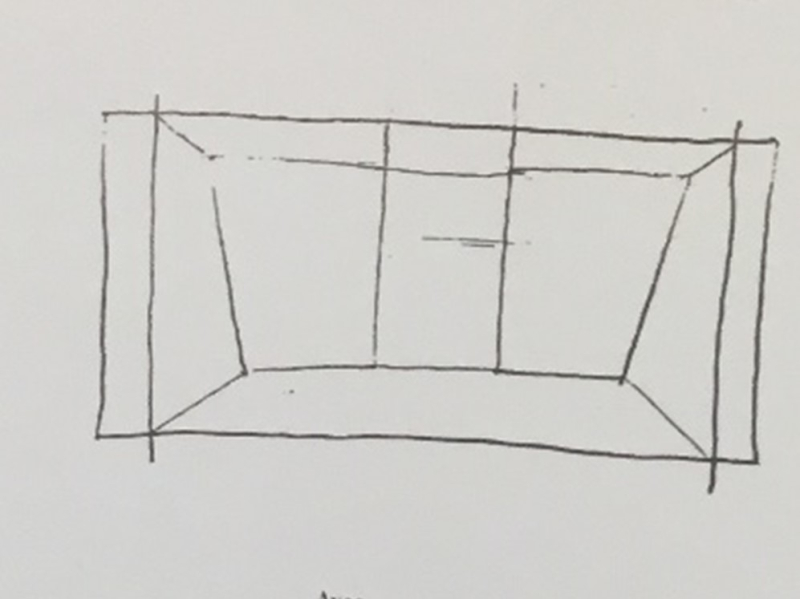

Rambert’s approach to scenography was resolutely minimalist. In his memoirs, the chapter devoted to scenography is entitled “The décor which kills”: “I did not believe in décors anymore”, he adds, explaining that “a décor was just another means to pile up more false elements on stage” (Rambert in Goumarre 49). He further argued that after Marcel Duchamp and the surrealist movement, it was impossible to content oneself with the exhibition of a makeshift illusion of the real world on stage.21 Fred Condom, his usual designer, left the stage bare, with grey walls in which several doors allowed for quick changes as the action switches from one location to another (one of the great difficulties of the play faced by directors). There were very few movable props, a golden chair of state, a suggestive white box (Figure 2: Sketch of the set) which could in turn represent Alexandria and Rome, Pompey’s galley or Cleopatra’s monument. This set certainly contributed to magnify the beautiful, deep voice of Dominique Reymond when she was playing inside the box then featuring her Alexandrian Palace.22 Due to the enclosed space, the sounds of her voice reached a fullness which reverberated and elongated the words she uttered. Her mezzo voice highlighted the beauty of the text and made her the dominant figure in this love story, even if Pascal Rambert meant to explore the theme of the play in a different perspective. At the end of act IV, Cleopatra and her women23 endeavour to lift Antony up to the top of the set representing then the monument, focussing on the general dying in the arms of his lover. In this sequence, Antony, who has failed in committing suicide the Roman way (unlike his servant Eros), seems to have lost all dignity and command of himself. The actor looked embarrassed and clumsy, with Cleopatra kneeling over him.

Figure 2. – White set, programme.

Archives of MC93 Bobigny.

II. A magnified love story

1. “And”

In his Introduction to the play, John Wilders states that “unlike Shakespeare’s early romantic tragedy, Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra is also a play about international politics, a public as well as a private drama in which Antony and Octavius compete for mastery over the Roman empire” (Wilders 2). In this production however, the international issues and political stratagems were completely by‑passed by Rambert who chose to concentrate his interpretation of the play on the two lovers. Indeed, he focused his attention on the title which contains the two names, the Roman General coming first, followed by the name of the Egyptian queen which sounds so seducing with a word full of vowels and ending with an assonance (in “a”) which can be elongated. Rambert wanted to set himself the challenge of proving that the title was right, “in spite of the play”, he writes, because Shakespeare did not write many scenes or sequences where Antony and Cleopatra are united. Rambert made it his single aim, to explore the conjunction “and” on a grammatical and theatrical point of view, considering it not as an addition or a measure “that can be reckoned” (1.1.15), but as the symbiotic nature of their attachment (Rambert in Goumarre 33). Antony and Cleopatra, a mature couple of exclusive lovers, experience passion when their hair is turning grey; Antony even says that he can still have the ardour of youth in war and in love, “Though grey / Do something mingle with our younger brown” (4.8.19–20) in an illusory attempt at trying to have a grip on reality. Rambert considered them as the late counterparts to Romeo and Juliet, the early epitome of devouring passion, as both couples are forever linked in the title of their tragedy. So, they can be defined as Romeo and Juliet grown old (see Solis 1995). In fact, in both plays, the Jacobean Roman tragedy and the Elizabethan Italian drama, the togetherness of the heroes is concluded forever “when they are alone in the monument hit by a love which will live after their deaths. So, this ‘and’ is death” (Rambert in Goumarre 34).24

Even before the production started, the previews had highlighted their high expectation towards the two actors who would play Antony and Cleopatra. Fabienne Pascaud, who is usually more prone to criticize than to praise, wrote enthusiastically of “a dream-like cast” (Pascaud 2019).25 And indeed, these very talented actors mastered their parts and gave a sense of their characters’ unnatural bond the one for the other. They showed that their love transcended duty and society, they were above friendship and even enmity. They dominated the cast, the play, and were the focal points of the production, in their shiny, golden gowns. They somehow eclipsed the other members of the cast. They were praised unanimously by all reviews alike, the only asset in an otherwise overtly critical, if not entirely negative assessment of the staging and scenography.26

2. Cleopatra’s triumph over her lover

However, on stage, the two lovers were not equal. Indeed, Cleopatra/Reymond dominated the production and had the favour of all the reviews. For one thing, the figure of the Egyptian queen has acquired a mythic status over the centuries, twice seducer of her successive invaders, Julius Caesar first and then Antony, the famous general who cannot fight against his devouring passion. Her story has been dealt with in many artistic forms and still fascinates. However, in his play, Shakespeare does not explore the success of the lovers but their story past the apex. Antony is seen on the decline, a man under influence, whose “goodly eyes [which] / Have glowed like plated Mars” (1.1.2/4) are now blinded by “dotage” and his “captain’s heart” has been “transformed / Into a strumpet’s fool” (1.2.12–13), according to the Roman conception of manhood and honour seen through the eyes of Renaissance England.

Jealous of Fulvia, then of Octavia, Cleopatra is ready to “sink Rome” (3.7.15) but it is Antony who is sinking, following Cleopatra even when her ship leaves the battle, and who must face his shame as a soldier: “My heart was to thy rudder tied by th’ strings” (3.11.57). Cleopatra has indeed enraptured the Roman General past the point of decent manhood. The actress showed perfectly well her determination to seduce and dominate her conqueror. Dominique Reymond was unanimously praised for her force of persuasion.27 Whereas André Marcon, for all his art, was considered as disappointing in this part: “Unfortunately, two people are necessary to enhance Cleopatra […] but André Marcon is absent, withdrawn” (Schmitt 1995).28 I presume the reviewers were expecting an imperial conqueror, but they saw a defeated “fool” (1.1.13), a loser, and also, an actor who may have had difficulties to find his own way against the management of their director.

III. “By sea, by sea” (3.7.40)

1. The flooded stage

According to Dominique Reymond, Pascal Rambert wanted to introduce three elements in his production: fire, hinted at by Cleopatra at the very end of the play, “I am fire and air” (5.2.288), certainly the colour of passion (some braziers were meant to burn on stage, but the idea was discarded because of the smoke); wind, or air (discarded as well because of the noise produced by the ventilators); and water, the only natural element which was maintained. In his memoirs, Rambert acknowledges the influence of Pina Bausch and her scenographer, Peter Pabst, for whom the surface of the stage is fundamental (Rambert in Goumarre 61). Rambert could have been influenced by a much earlier, much analysed, iconic play/dance, Arien, staged by Pina Bausch in 1979. Her dancers had to move barefooted in water, they would run, splash each other, fall; their costumes, heavy with water, became transparent; the lighting effects on the moving expanse of the water producing further scenic images.29

This calls to mind an earlier use of water on stage, if not even more spectacular, and equally famous also dating from the 1970s when experimentations were conducted in many directions. Patrice Chéreau, then a promising, challenging young assistant director to Roger Planchon at the TNP, Villeurbanne (in the suburbs of Lyons), had a real swimming‑pool on stage for the staging of Christopher Marlowe’s Massacre à Paris in 1972.30 The actors would be knee‑deep in water but could also walk on dry platforms set against a high tower. The actors splashing each other would produce most beautiful plumes of water which were enhanced by the lighting effects (see Bataillon 141–167). The comments described the effect of surprise and the pure beauty of the scenic images, the admiration being only tampered by financial considerations because it had meant extravagant expenditures (also see Goy-Blanquet 45–53).

Rambert used this kind of device. During the interval, the stagehands covered the stage with a thick sheet of plastic and filled it with about thirty centimetres of water thanks to four taps placed at each of the four corners. Dominique Reymond remembers the surprise of the spectators when they entered the auditorium after the interval [I must say I remember it too].

Indeed, for the second part of the performance, the stage was entirely under water. Rambert meant to stage literally the defeat of Antony’s navy at Actium. Antony, the Roman General who has led his soldiers to many victories on land, for the Roman Empire, and also for the sake of Cleopatra and her progeny, through blinded braggartry in front of Cleopatra, decides to fight by sea the other member of the former Triumvirate, now his opponent, whom he still later calls wrongly “the boy Caesar” (3.13.17): “We / Will fight with him by sea”, he declares to Canidius, a decision that Cleopatra echoes within the same line: “By sea, what else?” (3.7.28). He is warned against it, by Enobarbus first (“No disgrace. / Shall fall you for refusing him at sea, / Being prepared for land”, 3.7.38–40) and then, even by an unnamed soldier who dares contradict his master whom he senses has become weaker and has chosen the wrong strategy: “Trust not to rotten planks” (3.7.62). However, Antony is past listening to sound advice and goes blindly to his disgrace and the fall of all his followers.

2. Playing in the water

All the actors had to wear plastic shoes for the second part of the production. They were impeded in their progression on stage, Dominique Reymond remembers with a smile that they were somehow met with laughter from the audience as they splashed each other. Antony had to literally fight against the water “most lamentably” (3.10.26) to get to Cleopatra. The bottom of André Marcon’s toga getting darker as it became wet with water, he seemed to be impeded in his progression, having to fight against the mass of water. He was shown as physically defeated, clumsy, baffled by his own thoughtless decision, losing ground, and thoroughly ashamed of having followed his own inclination. Antony was clearly a loser in front of Cleopatra who seemed unable yet to fully understand the gravity of her act and their subsequent defeat. The actress seemed so much in control of her influence over Antony. She was a seducer to the end, with her elegant gestures, and, most of all, her beautiful voice which was magnified by the vibrations of the water.

At the end of the play, Cleopatra asks her women to dress her in her best attire: “Give me my robe. Put on my crown” (5.2.279). When she dies, Charmian closes Cleopatra’s eyes and sets her crown straight (“Your crown’s awry”, 5.2.317) so that her mistress appears as the royal queen that she was when Octavius Caesar and his train enter the monument (5.3.335–336). On stage Dominique Reymond wore a most beautiful full length pleated golden gown which shimmered in the light and a high golden tiara reminiscent of Nefertiti’s. When Cleopatra died, the tiara fell to the ground, the actress slowly knelt down, and remained head half immersed in the water for ten long minutes until the end of the performance, her kneeling figure being duplicated on the shiny surface of the water. As if Cleopatra could find some support from the element which gave her majesty to seduce Antony and which now can help her avoid the shame of being a captive in Rome. As opposed to Antony, a man of the land whose “legs bestrid the ocean” (5.2.81), Cleopatra enjoys the fluidity of the water, and is ready “again for Cydnus” (5.2.227). This conclusion provided a beautiful scenic picture, with silvery/grey lighting effects on the shiny surface of the water, even if the position was certainly not entirely comfortable for the actress.

Conclusion

When Pina Bausch and Patrice Chéreau challenged tradition with a stage covered with water, they were praised for their creativity because the water was really a dominant component of the scenography and staging, providing the dancers and actors with a material they could play with.

However, in this case, the water on stage was not taken favourably by the reviewers. One, even, whose excessive punctuation (exclamation marks, question marks, suspension points) translated the subjectivity of the author: “After the interval we find ourselves in a pool of water. Why? What is the symbol? We are furious, sad—so much waste …” (C. A. 1995).31 The pejorative connotation of the metaphor “pool of water”, the first-person plural and the choice of verb giving the impression that the audience were also in the water further contribute to this negative opinion.

The text of the play starts with a water metaphor and the sense of an excess (“o’flows the measure”, Philo. 1.1.2), however, strangely enough, not all the reviews mention the water on stage. This is the case of Olivier Schmitt who manages to devote three dense columns to this production (Schmitt 1995). René Solis, for instance, who explores the volcano metaphor of the programme at length, does not account for this unusual feature in the seven columns of his article, although the two pictures which are inserted concern sequences from the second part showing the shiny surface of the water: Eros raising his sword over kneeling Antony (4.14) and Cleopatra dying (end of performance). His only allusion to water is metaphorical in his negative conclusion: “This three‑hour and fifteen-minute voyage is a strange adventure in which the flashes are rare, but on which nonetheless floats Shakespeare’s spirit” (Solis 1995).32 Most of the references to water are metaphorical and provide negative puns, such as InfoMatin’s title “Who wants to drown Shakespeare…” and concluding sentence with a watery pun (Nicolet 1995), impossible to translate into English.33

These negative opinions criticize the stage effect without considering that this scenography could be seen as the scenic translation of the various excesses explored by Shakespeare, in particular the character of Antony who falls due to an excess of pride.

However, even if this production of Antony and Cleopatra proved so laden with conflict, it was a landmark for Rambert. He decided to leave Shakespeare’s plays aside, as well as any other canonical texts altogether; he discarded famous actors whose conceptions differed too much from his own, and staged only his literary production with the actors with whom he could feel a strong sense of empathy. His choice was indeed the right one: in 2016 he was awarded the prestigious Theatre Award of the French Academy for his work and career in the performing arts. Shakespeare is for all seasons, but perhaps not for all directors.