The notion of influence is a problematic one, that takes on different meanings when used in different contexts. This paper does not aim to establish Flaubert’s writing as the main influence, or indeed the driving force, behind Nabokov’s work. Not only was Nabokov’s work influenced by a certain number of writers just as important as Flaubert, such as Tolstoy or Pushkin, but both Nabokov’s and Flaubert’ staunch belief in the individuality of the artist makes such a perspective untenable. Flaubert proved this by his lifelong refusal to be associated with any literary movement, Nabokov by his claim that all great contributions to literature came from individual efforts, never collective ones. Andrew Field, in his biography of Nabokov, even wrote that for Nabokov the two words “individual artist” were inseparable (Field 146). In this case, influence should be seen as a link between the two works, stemming solely from Nabokov’s individual interpretation of Flaubert’s work. Nabokov, as a reader/writer, formed his own Flaubert as we all do when reading any book. Just as Gérard Genette indicates in his book Palimpsestes, where he stresses the importance of interpretation and the fact that when Proust imitates Flaubert’s style in his famous pastiche, it is only a “Flaubert read by Proust”. In the same way, Nabokov was not influenced by Flaubert but by a Flaubert read by Nabokov, whose style is made up of those of Flaubert’s stylistic idiosyncrasies that were picked up by the reader/writer Nabokov. Therefore, the force of individuality is not to be neglected but should be incorporated into the idea of influence: influence is seen as a movement starting from Nabokov’s singular reading of Flaubert’s singular invented world, and ending with the effect of this on Nabokov’s writing.

The immediate effect of Flaubert’s influence on Nabokov is the great number of references to Flaubert’s novels in Nabokov’s work. These references, which showcase Nabokov’s admiration for Flaubert’s work and his thorough reading of it, have been listed by Flaubertian specialists, notably in a “Nabokov” entry written by Isabelle Poulin in the 2017 Dictionnaire Flaubert (edited by Gisèle Séginger), but also by Nabokovians such as Maurice Couturier in his article “Flaubert and Nabokov” in the Garland Companion to Vladimir Nabokov (Alexandrov 405). Yannicke Chupin also, in her article “The Novel Is Alive”, published in Kaleidoscopic Nabokov (Delage-Toriel and Manolescu 107), compared L’Éducation sentimentale to Ada and notably pointed out that Van Veen, in the novel, is born on 1st January 1870, one year after the end of Frédéric Moreau’s story in Flaubert’s novel. Many other direct references are to be found, such as Flaubert’s being mentioned twice in Lolita, when Humbert Humbert uses what he calls the Flaubertian expression “nous connûmes” in an anaphora (Lolita, 145). The second occurrence is a meta‑literary allusion to the status of characters, in which Humbert Humbert deplores the inability of literary characters to change course, or Fate: “Never will Emma Rally, revived by the sympathetic salts in Flaubert’s father’s timely ear” (Lolita, 265). This shows Nabokov’s knowledge of Flaubert’s life and that of his family, Flaubert’s father having been a well‑known surgeon in the Rouen hospital. There are other references and deviated references in Ada, where Flaubert’s name is distorted into Floeberg,1 and Pale Fire, where the narrator points out that the device of synchronization used by the poet John Shade has already been used by Flaubert: “The whole thing strikes me as too labored and long, especially since the synchronization device has been already worked to death by Flaubert and Joyce” (Pale Fire, 157). Most of the references are to Madame Bovary though, thus illustrating Nabokov’s opinion—and his father’s before him—that this novel was “the unsurpassed pearl of world literature” (Speak, Memory, 134) and Flaubert’s best work. However, Nabokov, according to his letters to his wife, did read Flaubert’s complete works at least twice, including Flaubert’s correspondence, which he used in his Cornell class on Madame Bovary. In The Gift, where several references are made to Madame Bovary, is to be found a rare reference to Flaubert’s last, unfinished novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet, indicating that Nabokov had also read that novel and had it in mind, like Madame Bovary, when writing his own novels:

(Oddly enough, exhibitions in general, for instance the London one of 1862 and the Paris one of 1889, had a strong effect on his fate; thus Bouvard and Pécuchet, when undertaking a description of the life of the Duke of Angoulême, were amazed by the role played in it… by bridges). (The Gift, 209)

This reference is made in the fourth chapter, which is devoted to the narrator (Fyodor)’s critical biography of Chernyshevsky. By having his narrator compare his own effort to Bouvard and Pécuchet’s failed attempt at writing down the life of an “imbecile” (Bouvard et Pécuchet, 148), Nabokov uses Flaubert’s example of a failed biography to undermine his narrator’s comments.

Of course, the reasons why Nabokov makes numerous references to Flaubert and other writers vary, from a tribute paid to a beloved author to pure parody. Dale E. Peterson, in his article “Nabokov and Poe” in The Garland Companion, notes that Nabokov insisted on differentiating conscious from unconscious influence: “What is most telling about Nabokov’s repudiation of so‑called literary influence is his assumption that awareness of a stylistic echo removes the spell of an ancestor. It mattered to Nabokov to be clear about matters of apparent sameness; he drew careful distinctions between conscious and unconscious resemblances” (Alexandrov 463). According to Peterson, while Nabokov’s parodies may also be attempts at defusing the notion of influence—in the same fashion as he attempts to defuse the “Viennese delegation”’s psychoanalytical interpretations in advance by introducing fake primal scenes in his novels—they also paradoxically link Nabokov’s work to his reading of his precursors’ works: “These parodies allowed Nabokov to distance himself from subjection to the ‘influence’ of Poe while consciously (and ironically) continuing to cultivate Poe’s poetic principles in a post‑Romantic age” (Alexandrov 463). Moreover, Peterson points out Nabokov’s specific vision of parody, one of a stylistic game which feeds off the precursor’s work rather than a mockery of it: “Nabokov […] sensed in the parody not a ‘grotesque imitation’, but a playful collision of tradition with critical talent, as in his praise of Joycean parody for the ‘sudden junction of its clichés with the fireworks and tender sky of real poetry’ (SO 75–76)” (Alexandrov 465). Such parody may be found in a particular novel written by Nabokov: King, Queen Knave. Maurice Couturier, in his article on Flaubert and Nabokov from The Garland Companion, writes that King, Queen, Knave is a “parodic version of Flaubert’s masterpiece” (Alexandrov 409), Madame Bovary. Nabokov, in the preface, writes that his “imitations” of Flaubert’s novel constitute a “deliberate tribute”. As Genette indicates, there is no perfect imitation, not even a copy, and the remaining question is that of the degree of transformation. The theme of the two novels is indeed similar, a story of adultery which gradually turns into a story of despair and near insanity, culminating in the death of the female protagonist. There are also many differences, such as the age difference between the lovers, a “remotivation” in Genettian language (Genette 457), or Martha’s husband’s complete indifference to his wife’s demands and longings, compared to Charles Bovary’s clumsy attentions, cluelessness and desperate true love for Emma, analysed by Genette as “transmotivation” (Genette 458). As Nabokov indicates, the real parody seems to lie in a few passages dealing with the common theme of adultery, such as the philandering wife’s escapades and her adulterous thoughts.

Maurice Couturier has identified some of those passages, pointing out that the name of Martha’s trainer, Madame L’Empereur, is very close to that of Emma’s piano teacher, Mademoiselle l’Empereur (the same reference is to be found in Lolita, where the girl’s piano teacher is called “Miss Emperor”) (Lolita, 202). Another blatant reference Couturier mentions is the example of the slippers, a gift from Léon in Madame Bovary: “Des pantoufles en satin rose, bordées de cygne” (Madame Bovary, 397). In King, Queen, Knave, they become a « pair of slippers, (his modest but considerate gift) our lovers kept in the lower drawer of the corner chest, for life not unfrequently imitates the French novelists » (King, Queen, Knave, 128). Here Nabokov appropriates the Flaubertian objects or names and incorporates them into his own novel and in his own style, but acknowledges said borrowing. However, this hardly constitutes imitation, and is more in line with other references to Flaubert, where Nabokov seems to test his reader’s knowledge, establishing “une condition de lecture” (Genette 31), to use yet another expression by Genette. This type of references may serve another purpose for an author who rejected any notion of influence as applied to himself. Indeed, by resorting to explicit references Nabokov may have been trying to dismiss any assumption of covert traces of influence in his work, in the same way as he inserts false primal scenes and psychological symbolism in other novels to refute psychoanalytical interpretation (the oranges in Mary, the running taps in Pale Fire). By displaying the reference, Nabokov may be exhibiting his awareness of Flaubert’s work to discard the idea of a more profound influence of the Norman writer upon his work.

Likewise, his allusions to “amiable imitations” in the preface indicate that all similarities with Flaubert’s work are not coincidental but intentional. Indeed, several passages in the two novels mirror each other. The first one is located right after the adultery has taken place for the first time, as the female protagonist reflects upon her actions. In the two novels, the depiction begins with the same event: the character observing her own reflection in the mirror, and rediscovering herself.

In Madame Bovary:

[…] Mais, en s’apercevant dans la glace, elle s’étonna de son visage. Jamais elle n’avait eu les yeux si grands, si noirs, ni d’une telle profondeur. Quelque chose de subtil épandu sur sa personne la transfigurait.

Elle se répétait : « J’ai un amant ! un amant ! » se délectant à cette idée comme à celle d’une autre puberté qui lui serait survenue. Elle allait donc posséder enfin ces joies de l’amour, cette fièvre du bonheur dont elle avait désespéré. Elle entrait dans quelque chose de merveilleux où tout serait passion, extase, délire ; une immensité bleuâtre l’entourait, les sommets du sentiment étincelaient sous sa pensée, et l’existence ordinaire n’apparaissait qu’au loin, tout en bas, dans l’ombre, entre les intervalles de ces hauteurs. (Madame Bovary, 266)

In King, Queen, Knave:

She proceeded to change, smiling, sighing happily, acknowledging with thanks her reflection in the mirror. […] It’s all quite simple, I simply have a lover. That ought to embellish, not complicate, my existence, And that’s just what it is—a pleasant embellishment.” (King, Queen, Knave, 125/140)

Again, Nabokov borrows the theme from Flaubert, the character seeing her renewed self in the mirror, and pondering her having finally become the “woman with her lover” she had been longing to be since the beginning of the novel. However, the style is still Nabokovian, and this particular imitation seems to fit the notion of parody as described by Genette in Palimpsestes, a “playful transformation” (“transformation ludique”, p. 45). It is actually not technically an imitation, but what Genette would call a transformation, since the reactions displayed are quite different: Emma Bovary is portrayed as ecstatic at having finally fulfilled her idealistic vision of love derived from her sentimental reading of Walter Scott and other romantic novels, and Flaubert seemingly mocks his character for her illusions by overdoing her satisfaction (which, compared with the novel’s ending, is decidedly ironic). Martha is described as composed, assessing her adultery as her access to a new, improved social status. The effect is humorous for a reader of Madame Bovary, as Nabokov pointed out in his preface. The passage therefore constitutes a playful transformation, and differentiates Nabokov’s character from Flaubert’s, which Nabokov makes clear in the next page: “She was no Emma, and no Anna.” But Nabokov also pursues Flaubert’s already ironical description of his protagonist. In Madame Bovary, the description of Emma’s feelings is incredibly emphatic, Flaubert describing Emma’s recaptured femininity, as illustrated by the anaphora of “she”, in the final unleashing of emotions which had been portrayed as frustrated for the last 200 pages. Martha’s mild reaction highlights Emma Bovary’s deluded state of mind, which Flaubert already attempted to convey through several exclamation points, and an enumeration of cliché expressions such as “fever of happiness”, “passion”, “ecstasy” and “delirium”. Nabokov showcases his interpretation of Emma Bovary’s character and brings Flaubert’s emphatic description one step further.

Yet other aspects of influence may be shown by those passages that were directly referenced by Nabokov in his preface. In that particular excerpt, Nabokov borrows not only a theme used in Madame Bovary, but also seems to briefly imitate Flaubert’s style. In this scene, Emma and Martha visit their lovers, Rodolphe for Emma and Franz for Martha. In the preface, Nabokov writes that he “remembered remembering” “Emma creeping at dawn to her lover’s chateau along impossibly unobservant back lanes”. The passage thus reads:

Un matin, que Charles était sorti dès avant l’aube, elle fut prise par la fantaisie de voir Rodolphe à l’instant. On pouvait arriver promptement à la Huchette, y rester une heure et être rentré dans Yonville que tout le monde encore serait endormi. […] Cette première audace lui ayant réussi, chaque fois maintenant que Charles sortait de bonne heure, Emma s’habillait vite et descendait à pas de loup le perron qui conduisait au bord de l’eau.

Mais, quand la planche aux vaches était levée, il fallait suivre les murs qui longeaient la rivière ; la berge était glissante ; elle s’accrochait de la main, pour ne pas tomber, aux bouquets de ravenelles flétries. Puis elle prenait à travers des champs en labour, où elle enfonçait, trébuchait et empêtrait ses bottines minces. Son foulard, noué sur sa tête, s’agitait au vent dans les herbages ; elle avait peur des bœufs, elle se mettait à courir ; elle arrivait essoufflée, les joues roses, et exhalant de toute sa personne un frais parfum de sève, de verdure et de grand air. (Madame Bovary, 267–268)

The passage from King, Queen, Knave is shorter, but mirrors Emma’s escapades:

More and more often, with a recklessness she no longer noticed, Martha escaped from that triumphant presence to her lover’s room, arriving even at hours when he was still at the store and the vibrant sounds of construction in the sky were not yet replaced by nearby radios, and would darn a sock, her black brows sternly drawn together as she awaited his return with confident and legitimate tenderness.

The common theme here is the character’s impatience, which conveys the irresistible nature of her affair. Martha’s “recklessness” echoes Emma’s “bold venture”. As in the other passage, the transformation of “plowed fields” and “pastures” into “vibrant sounds of construction” and “cattle” into “nearby radios” is playful. However, Nabokov’s use of the form “would + verb” as he describes Martha’s repeated actions when she “would darn a sock” is more telling, as it illustrates the influence on Nabokov’s style of his vision of Flaubert’s style. In Flaubert’s passage, he uses the famous “éternel imparfait” as Proust dubbed it, so as to describe actions which are repeated by his characters in an habitual manner. In his class on Madame Bovary, Nabokov had to retranslate part of Madame Bovary for his students, since he disliked Eleanor Marx’s available translation, particularly because she had eliminated Flaubert’s specific use of the “imparfait” verb tense, to rather translate all its forms by preterits. This is what Nabokov says of Flaubert’s use, and of the appropriate translation:

Another point in analyzing Flaubert’s style concerns the use of the French imperfect form of the past tense, expressive of an action or state in continuance, something that has been happening in an habitual way. In English this is best rendered by would or used to: on rainy days she used to do this or that; then the church bells would sound; the rain would stop, etc. Proust says somewhere that Flaubert’s mastery of time, of flowing time, is expressed by his use of the imperfect, of the imparfait. This imperfect, says Proust, enables Flaubert to express the continuity of time and its unity.

Translators have not bothered about this matter at all. In numerous passages the sense of repetition, of dreariness in Emma’s life, for instance in the chapter relating to her life at Tostes, is not adequately rendered in English because the translator did not trouble to insert here and there a would or used to, or a sequence of woulds.

In Tostes, Emma walks out with her whippet: “She would begin [not “began”] by looking around her to see if nothing had changed since the last she had been there. She would find [not “found”] again in the same places the foxgloves and wallflowers, the beds of nettles growing round the big stones, and the patches of lichen along the three windows, whose shutters, always closed, were rotting away on their rusty iron bars. Her thoughts, aimless at first, would wander [not “wandered”] at random […].” (Lectures on Literature, 173)

In the latest translation of Madame Bovary by Lydia Davis, Flaubert’s imperfect has also been translated by would. For example, this is how she translates the ending of the second passage:

Then she would strike out across the plowed fields, sinking down, stumbling, and catching her thin little boots. Her scarf, tied over her head, would flutter in the wind in the pastures; she was afraid of the cattle, she would start running; she would arrive out of breath, her cheeks pink, her whole body exhaling a cool fragrance of sap, leaves, and fresh air.

Lydia Davis, in a presentation at the Center of Translation, explained that she examined Nabokov’s annotations and commentaries and used them in her own translation (Davis), a rare example of inverse influence, whereby Nabokov’s vision of Flaubert’s imperfect becomes part of the reading experience of Madame Bovary by English-speaking readers.

At any rate, this proves that Nabokov was well aware of the significance of this device as well as of the specific intonation it granted to Flaubert’s style, so that its use in this passage, already Flaubertian in its theme, constitutes an imitation by Nabokov of Flaubert’s style. This is not an isolated use of such value and effect of the imperfect tense by Nabokov though. Indeed, in Lolita, Nabokov uses would to describe “something that has been happening in a usual way”:

[…] she would set the electric fan-a-whirr or induce me to drop a quarter into the radio, or she would read all the signs and inquire with a whine why she could not go riding up some advertised tail […] Lo would fall prostrate […] and it would take hours of blandishments, threats and promises to make her lend me for a few seconds her brown limbs […]. (Lolita, 147)

In this passage, Nabokov sums up a large period of time through repeated actions, like Flaubert did through the use of the imparfait. In Ada, as well: “[…] she would clench them, allowing his lips nothing but knuckle, but he would fiercely pry her hand open to get at those flat blind little cushions” (Ada, 59).

Still, transformation intervenes. Indeed, Nabokov’s interpretation of Flaubert’s imparfait is unique in its focus on the imparfait as expressing “a state or action in continuance”. When Nabokov writes that “Proust says somewhere that Flaubert’s mastery of time […] is expressed by his use of the imperfect”, he is most likely alluding to Proust’s 1920 article, “Sur le style de Flaubert”. Yet, in this article, Proust lists several uses of Flaubert’s imparfait, including but not limited to continuing actions or states. Indeed, he also mentions Flaubert’s use of the imparfait to convey characters’ speech in free indirect speech, quoting this passage from L’Éducation sentimentale: “L’État devait s’emparer de la Bourse. Bien d’autres mesures étaient bonnes encore. Il fallait d’abord passer le niveau sur la tête des riches […]” (Philippe 2004, 86). Nabokov, however, does not mention this use, and selects one of the effects of Flaubert’s use of the imparfait. Nor does Nabokov’s vision fully match Gilles Philippe’s depiction of Flaubert’s “imparfait phénoméniste”, which “when substituted to the expected simple past, shows the unfolding of action, which seems to be much less of an event, and as it is perceived by a consciousness: ‘Mlle Marthe courut vers lui, et, cramponnée à son cou, elle tirait ses moustaches’”.2 This example depicts a singular, unrepeated action expressed continuously, not “something that has been happening in an habitual way”. At any rate, Nabokov’s interpretation creates a Nabokovian version of Flaubert’s imparfait which is focused on expressing the continuity of repeated actions. Moreover, the use of “would” in Nabokov’s work seems to be reserved for love relationships between his characters, and the modal would is often written by a first‑person narrator, not only to convey an impersonal and forlorn description of a character trapped in a repetitive state, like Flaubert did, but also the homodiegetic narrator’s obsession, so that the repetitive state is also induced by this narrator as a character. Even in Pale Fire, where Kinbote describes a recurring dream by the King about the Queen Disa, the use of would has to do with love and obsession:

These heartrending dreams transformed the drab prose of his feelings for her intro strong and strange poetry, of which would flash and disturb him throughout the day […] He would see her being accosted by a misty relative so distant as to be practically featureless. She would quickly hide what she held and extend her arched hand to be kissed […] She would be cancelling an illumination, or discussing hospital cost with the head nurse […] He would help her again to her feet and she would be walking side by side along an anonymous alley, and he would feel she was looking at him […]. (Pale Fire, 168)

The idea of Nabokov being influenced by his own interpretation of Flaubert seems quite relevant here. His vision of Flaubert’s imparfait, as described in his class on Madame Bovary and used in the above-quoted passages, is selective. Indeed, Proust explains that Flaubert also uses the imperfect tense to convey his character’s speech indirectly, or a clichéd speech, while Thibaudet’s view is that it sometimes serves to mark a brutal return to reality for the characters. Yet Nabokov only retained one of the values or effects of the Flaubertian imperfect. Therefore, his using the modal would as an equivalent for the French imparfait illustrates the importance of the reader/writer’s interpretation in the phenomenon of influence.

Nabokov explores the would device in his class on Madame Bovary, in the “Flaubert’s style” section, the would device being the fourth identified feature in Flaubert’s style. Just as interesting when it comes to analyzing the influence of Flaubert’s work on Nabokov is the first device mentioned: the use of the semi‑colon and coordination conjunction “and”. Here is what Nabokov says about this structure:

In order to plunge at once into the matter, I want to draw attention first of all to Flaubert’s use of the word and preceded by a semi‑colon. (The semicolon is sometimes replaced by a lame comma in the English translation, but we will put the semicolon back.) This semicolon-and comes after an enumeration of actions or states or objects; then the semicolon creates a pause and the and proceeds to round up the paragraph, to introduce a culminating image or a vivid detail, descriptive, poetic, melancholy, or amusing. This is a peculiar feature of Flaubert’s style.

[…] Emma bored with her marriage at the end of the first part: “She listened in a kind of dazed concentration to each cracked sound of the church bell. On some roof a cat would walk arching its back in the pale sun. The wind on the highway blew up strands of dust. Now and then a distant dog howled; and the bell, keeping time, continued its monotonous ringing over the fields.” (Lectures on Literature, 171)

Again, Nabokov’s interpretation of this device highlights the importance of the reader’s individuality when it comes to influence. Proust, in his study of Flaubert’s style, considers that Flaubert’s suppression of “and” in enumerations is just as significant as his use of it, and does not mention the semi‑colon and as a way to “round up the paragraph”. Rather he focuses on its introducing a secondary sentence, but never ending an enumeration: “En un mot, chez Flaubert, ‘et’ commence toujours une phrase secondaire et ne termine jamais une énumération” (Philippe 2004, 88). Thibaudet, in his study of Flaubert’s style and of his use of “and”, does not mention any particular punctuation associated with it, even for the “and” of “movement” as he calls it, which most resembles Nabokov’s depiction of the device: “[…] et de mouvement qui accompagne ou signifie au cours d’une description ou d’une narration le passage à une tension plus haute à un moment plus important ou plus dramatique, une progression” (Thibaudet 265).

Once again, this Flaubertian device as seen by Nabokov can be found in several of Nabokov’s novels. In Lolita, for example, in a paragraph where the would is also present:

She sat a little higher than I, and whenever in her solitary ecstasy she was led to kiss me, her head would bend with a sleepy, soft, drooping movement that was almost woeful, and her bare knees caught and compressed my wrist, and slackened again; and her quivering mouth, distorted by the acridity of some mysterious potion, with a sibilant intake of breath came near to my face. (Lolita, 14)

The first two “ands” are quite different from the last. They merely coordinate the various clauses, which express successive actions depicting a scene of calm and affection. The semicolon, as described by Nabokov in his class on Madame Bovary, creates a pause in the scene, while the and introduces a culminating clause, including the vivid, slightly jarring, detail of the “quivering mouth”. Likewise, Nabokov uses the preterit in the sentence introduced by “; and” contrasting with the “would + verb” construction of the first sentence, in the same way as Flaubert uses the simple past after the imperfect. In Flaubert’s work, this is not systematic. He sometimes also uses the imperfect for his last sentence, as can be seen in one of the examples quoted by Nabokov in his class: “[…] and she would push him away, half‑smiling, half‑vexed, as you do a child who hangs about you”3 (Lectures on Literature, 171). Whenever Nabokov makes a similar use of “; and”, however, he often uses the preterit, or another tense, but rarely the “would + verb” construction. The effect of this is a flattening of the continuous effect created by the imperfect or the “would + verb” construction. In Flaubert, even the simple past, describing an instantaneous action, gives an impression of slowness and doomed repetition, as indicated by the verb “continue” and the adjective “monotonous” in: “[…]; and the bell, keeping time, continued its monotonous ringing over the fields”4 (Lectures on Literature, 171). This is due to Flaubert’s “; and” device having the intention both to “heighten the tension” as Thibaudet pointed out, but also, as Nabokov taught in his class to “round up” (Lectures on Literature, 171) the sentence, the paragraph or the chapter. Nabokov only very rarely uses “; and” to end a chapter, which, in addition to the difference in the use of tenses, indicates that Nabokov’s use of the device introduces a jarring or culminating clause rather than “round[s] up” the sentence.

That Nabokov should have had culmination as an aim when using “; and” is corroborated by a difference in rhythm. In all examples given by Nabokov of Flaubert’s use of the device, the clauses introduced by “; and” take up only one or two lines, serving their purpose as conclusions of the sentence. However, Nabokov often introduces much longer clauses with the same device, sometimes amounting to explanatory digressions, as is the case in this quote from Ada:

A freshly emerged Nymphalis carmen was fanning its lemon and amber‑brown wings on a sunlit patch of grating, only to be choked with one nip by the nimble fingers of enraptured and heartless Ada; the Odettian Sphinx had turned, bless him, into an elephantoid mummy with a comically encased trunk of the guermantoid type; and Dr Krolik was swiftly running on short legs after a very special orange‑tip above timberline, in another hemisphere, Antocharis ada Krolik (1884)—as it was known until changed to A. prittwitzi Stümper (1883) by the inexorable law of taxonomic priority. (Ada, 56–57)

In this passage, Nabokov seems to follow Flaubert’s use of the device, rounding up the phrase with a culminating image, in this case Dr Krolik chasing a butterfly. Yet, unlike what happens in Flaubert’s prose, Nabokov continues the sentence, introducing such vivid details as the two names of the butterfly, and several events, letting the reader know that Dr Krolik did catch the butterfly, but was beaten to the discovery by another lepidopterist. This is part of a pattern in Nabokov’s use of “; and” where, instead of Flaubert’s sharp, riding up clause, which heightens the tension by jarring with the previous slow enumerations, Nabokov introduces several images and details, as if starting on another idea altogether, so that instead of concluding the sentence, his last clause takes on a life of its own and becomes a series of culminating images.

The two authors’ different uses of “; and” reflect a disparity in style and a decidedly original take on the device by Nabokov. Indeed, Nabokov’s excess disconnects the device from the main clause. In the first example taken from Lolita, the playful description of the character’s movements shifts into a darker depiction: “[…] her quivering mouth, distorted by the acridity of some mysterious potion” (Lolita, 14). These details clash with the tone created in the previous enumeration of actions. Thus the change in tone combines with the culminating effect. The following lines, taken from John Shade’s poem in Pale Fire, offer a particularly striking example of this:

We’ll think of matters only known to us—

Empires of rhyme, Indies of calculus;

Listen to distant cocks crow, and discern

Upon the rough gray wall a rare wall fern;

And while our royal hands are being tied,

Taunt our inferiors, cheerfully deride

The dedicated imbeciles, and spit

Into their eyes just for the fun of it. (Pale Fire, 47)

The structure of the poem separates “and” from the semicolon having remained in the preceding line. However, the basic pattern remains: an enumeration of images and actions, “empires of rhyme, Indies of Calculus”, “distant cocks”, “a rare wall fern” is broken by a pause in the action, marked by the semicolon. The “and” which follows introduces a culminating image. This last clause also concludes the sentence, but Nabokov introduces another “and” in the sentence, thus prolonging it so that it makes up half of the stanza. Nabokov’s deviation from his Flaubertian model is illustrated here, as the culminating image seems to have little to do with the beginning of the stanza. Indeed, the seemingly peaceful enumeration, painting a still picture in which one might use the Flaubertian imperfect without conflict with the original tone (“the distant cocks would crow”) is followed by a striking depiction of a King who, having been made prisoner, maintains a shockingly cavalier and contemptuous attitude.

Nabokov’s immoderate style pushes the Flaubertian culmination further so that the clause introduced by “; and” dwarfs the sentence beginning the poem rather than concludes it or “round[s] it up”. This likely has to do with Nabokov’s use of the first-person narrator, compared to Flaubert’s third person, neutral narrator, better appropriate to achieve Flaubert’s commitment to the impersonality of the writer. Nabokov, on the contrary, impersonates a character, and in this case a poet, John Shade, whose style is also largely Nabokov’s, although its exuberance and excess probably also indicate a shift in the character’s mindset. Such deviation from Flaubert’s use of “; and” is not the only one of its kind.

Indeed Nabokov finishes the novel Ada with a clause introduced by “; and”. The rhythm of the Flaubertian device is present, as Nabokov enumerates several images before coming to a break with the semicolon:

Not the least adornment of the chronicle is the delicacy of pictorial detail: a latticed gallery; a painted ceiling; a pretty plaything stranded among the forget‑me‑nots of a brook; butterflies and butterfly orchids in the margin of the romance; a misty view descried from marble steps; a doe at gaze in the ancestral park; and much, much more. (589)

Despite the similarity in rhythm, a crucial element of the Flaubertian device is missing, as the “; and” structure fails to introduce a striking image, detail or action. Instead, a simple comparative, preceded by a quantifier repeated once, without a verb, forms the whole clause. Nor does it “round up” the sentence, the paragraph, nor the novel itself. Quite the contrary, as the very brief clause suggests that all preceding images only make up a small portion of the imagery of the lovers’ story. Thus the device is made to serve almost the opposite purpose it does in Flaubert, since, instead of concluding an enumeration by a culminating detail, the clause introduced by “; and” rather opens the sentence out, conjuring up a new enumeration of images, sometimes even unrelated to the beginning of the sentence. The enumeration being kept silent further stimulates the reader’s imagination, giving way to a wide possibility of interpretations. This may be the major difference in the use of the “; and” by Flaubert and Nabokov. Flaubert uses the device to seal the sentence and engrave in the reader’s mind the last striking detail. In Nabokov’s prose, it seems to launch the sentence anew, breaking as it does from the beginning of the sentence to trigger flights of fancy and release new images.

What can Nabokov’s appropriation of the Flaubertian “; and” device and deviation from it tell us about the issue of influence? In The Anxiety of influence, Blooms lists different types of influence corresponding to different postures taken by the influenced authors in regards to their predecessors (Bloom 1973, 14). To Bloom, influence can manifest itself in the form of imitation, continuation, complete deviation, recreation, appropriation, and even destruction. The type of influence described by Bloom which may best fit Flaubert’s influence upon Nabokov seems to be what he calls Tessera: “[…] which is completion and antithesis. […] A poet antithetically ‘completes’ his precursor, by so reading the parent-poem as to retain its terms but to mean them in another sense, as though the precursor had failed to go far enough” (Bloom 1973, 14). As has been seen through Nabokov’s specific interpretation of Flaubert’s imperfect tense and “semicolon‑and” devices and his subsequent original uses of it, Nabokov seems to adopt Flaubertian turns only to take them in another direction.

The issue of interpretation as raised by this definition, however, relies on the key notion of “misreading”, defined by Bloom as follows: “Poetic history, in this book’s argument, is held to be indistinguishable from poetic influence, since strong poets make that history by misreading one another, so as to clear imaginative spaces for themselves” (Bloom 1975, 5). Misreading is thus seen as an inevitable deviation operated by the individual reading another’s work, so that appropriation and interpretation of said work begins with the act of reading: “Reading, as my title indicates, is a belated and all‑but impossible act, and if strong is always a misreading” (Bloom 1975, 3). While the individual deviation operated by any reader on the text does seem inevitable, the “mis‑” prefix indicates a necessary flawed interpretation on the reader’s part. This would require the existence of a true meaning of the text from which the individual reading would part. Nabokov’s analysis of Flaubert’s writing in his class certainly constitutes an individual vision of Flaubert but not necessarily a misinterpretation. Rather, his knowledge of Flaubert’s work and his creative take on Flaubert’s writing showcase the power of his “mis”‑reading. His having translated passages of the novel himself rather than using an existing translation is more evidence of the originality of his reading: he created a Flaubert of his own, in agreement with his personal interpretation. Indeed, although his issues with Marx-Aveling’s translation come from a complex understanding of Flaubert’s style, specifically Flaubert’s use of past tenses, Nabokov himself argues that a purely scholarly translation will not be an effective one if it lacks the essential quality of creativity:

The scholar will be, I hope, exact and pedantic […] The laborious lady translating at the eleventh hour the eleventh volume of somebody’s collected works will be, I am afraid, less exact and less pedantic; but the point is not that the scholar commits fewer blunders than a drudge; the point is that as a rule both he and she are hopelessly devoid of any semblance of creative genius. Neither learning nor diligence can replace imagination and style. (Nabokov 1941)

Such creative genius implies invention on the part of the translator and originality, as stemming from an individual and subjective input. When Nabokov wrote his book on Gogol, he claimed that by translating him he had “created” him: “I had first to create Gogol (translate him) and then discuss him (translate my Russian ideas about him)” (Boyd 63). In the same way he created “his” Gogol, Nabokov created “his” Flaubert at the same time as he was influenced by the latter. Misreading therefore appears to have much to do with the reader’s individuality as it influences his reception of the author’s work. In his essay Comment parler des livres que l’on n’a pas lus, Pierre Bayard discusses the existence of an “inner book”, formed by the reader’s experience and previous readings:

Tissé des fantasmes propres à chaque individu et de nos légendes privées, le livre intérieur individuel est à l’œuvre dans notre désir de lecture. […] les livres intérieurs individuels forment un système de réception des autres textes et interviennent à la fois dans leur accueil et dans leur réorganisation. En ce sens, ils constituent une grille de lecture du monde, et particulièrement des livres, dont ils organisent la découverte en donnant l’illusion de la transparence. Ce que nous prenons pour des livres lus est un amoncellement hétéroclite de fragments de textes, remaniés par notre imaginaire et sans rapport avec les livres des autres […]. (83–84)

As much as in Bloom’s notion of misreading, Bayard’s view suggests that the reader’s imagination and ideas command his interpretation of the text, since each reading operates an individual deviation from the author’s work. Such is the idea expressed by Pascal about Montaigne’s influence upon him, quoted by Bloom in The Anxiety of Influence: “It is not in Montaigne, but in myself, that I find all that I see in him” (Bloom 1975, 56). Bloom dismisses this assertion as an effort by an anxious Pascal to distance himself from a precursor with whom he shares many “parallel passages” (Bloom 1975, 56). Yet, in this sentence, Pascal articulates a vision of the reader’s creating an individual text, born of a selection of ideas, while discarding others having appeared in the course of reading. The fear of seeing one’s individuality dismissed may be the reason for what Bloom calls the anxiety of influence, and why many authors are reluctant to admit their having been influenced. Nabokov is one of them. In a 1932 interview with the Estonian newspaper “Today”, quoted by Field, he agreed that “one might speak of a French Influence. I love Flaubert and Proust” (Field 115). However, he also minimized his precursors’ influence in a 1964 interview with Life magazine, while conceding some occasional similarities between his writing and his past readings:

Today I can always tell when a sentence I compose happens to resemble in cut and intonation that of any of the writers I loved or detested half a century ago; but I do not believe that any particular writer has had any definite influence upon me. (Strong Opinions, 46)

The issue thus seems to lie in the definition of influence rather than in deciding whether he was influenced or not. Indeed, Nabokov declared in his class that “Without Flaubert there would have been no Marcel Proust in France, no James Joyce in Ireland. Chekhov in Russia would not have been quite Chekhov. So much for Flaubert’s literary influence” (Lectures on Literature, 147). Would Nabokov, who wrote to his wife Véra that he had read Madame Bovary “a hundred times” (Voronina and Boyd 173), have been Nabokov without Flaubert? Probably not, but Nabokov’s reluctance to discuss this influence may stem from his deep concern for the artist’s individuality, and from his vision of influence as a “dark and unclear thing” (Field 265). However, when seen in light of the notion of misreading, the fact that Nabokov created his own Flaubert by reading his whole works in Russia between the age of 14 and 15, may allow for a definition of influence which would fully take into account the influenced author’s individuality.

Derek Attridge, in The Singularity of Literature, gives a definition of influence inspired by Kant’s “exemplary originality”, described as a “type of genius” which “provides both a pattern for methodical reproduction by future artists lacking in genius and more significantly, a spur to future geniuses for the further exercise of exemplary originality” (Attridge 36). Influence is not only perceived as a source of anxiety for the influenced author, struggling to overcome his precursor’s “genius”, but also as a stimulus for the reader/writer’s creativity. Flaubert himself, in his letters, describes this dual feeling when he discusses his reading of Shakespeare. In 1845, in a letter to Alfred le Poittevin, he writes: “Plus je pense à Shakespeare, plus j’en suis écrasé” (Correspondance I, 247). In 1846, to Louise Colet, he expresses a different feeling: “Quand je lis Shakespeare je deviens plus grand, plus intelligent et plus pur. Parvenu au sommet d’une de ses œuvres, il me semble que je suis sur une haute montagne : tout disparaît et tout apparaît. On n’est plus homme, on est œil ; des horizons nouveaux surgissent, les perspectives se prolongent à l’infini […].” (Correspondance I, 364)

In Palimpsestes, Genette argues that even a writer with a strong “stylistic individuality” (he quotes Nabokov as an example) cannot be free of influence:

[…] une individualité littéraire (artistique en général) peut sans doute difficilement être à la fois tout à fait hétérogène et tout à fait originale et « authentique » — si ce n’est dans le fait même de son éclatement, qui transcende et de quelque manière rassemble ses éclats, comme Picasso n’est lui‑même qu’à travers des manières qui l’apparentent successivement à Lautre, à Braque, à Ingres, etc. (176)

Originality and influence are therefore not incompatible at all, and influence may be seen as a two‑fold movement of continuity and deviation, the influenced author’s individuality being the driving force behind the two phenomena: continuity, because Nabokov carries forward not Flaubert’s work but the work of “his” Flaubert, a vision born of his misreading; and deviation because Nabokov departs from this vision by exploring different ideas.

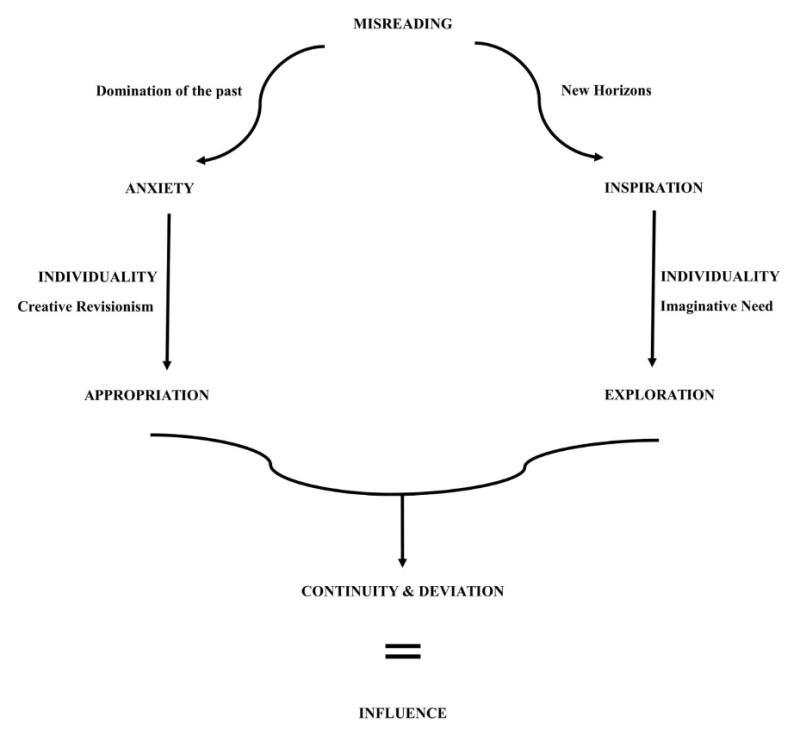

Such a process may be summarized by the following scheme:

Illustration 1. – Scheme of the process from misreading to influence.

Misreading is the fundamental element, leading the influenced author to produce an individual reading of the author’s work, in this case Nabokov’s misreading of Flaubert. Then, the reader/writer is faced with two paths, which he follows simultaneously: inspiration, marked by an enthusiastic discovery of new ideas and horizons found in the precursor’s work. This corresponds to what Flaubert wrote about being inspired by Shakespeare, and Attridge’s description of “exemplary originality” as a “spur for futures geniuses”. The second path is anxiety, fueled respectively by a feeling of being dominated by past achievements, again described by Flaubert, but which Nabokov also expressed in poems such as “Fame”, where the poet declares that his work is doomed to be forgotten. Afterwards, individuality, the key factor in the process, transforms impressions into actions, as the act of writing follows the act of reading. Such are the two axes of influence: inspiration leads to the precursor’s ideas being further explored and experimented with, while anxiety, which also induces creativity, leads to an individual interpretation and appropriation of the predecessor’s work.

The impact of individuality may best be described once again through the example of Flaubert’s “; and” device. Nabokov interpreted that device in his own way, describing the break made after an enumeration, followed by a culminating detail. This leads to Nabokov’s appropriation of the device, put to use in his own works but not copied. Nabokov is the one who discarded the other uses of Flaubert’s “; et” alluded to by Zola and Thibaudet and singled out its usage as the conclusion of a sentence. This concords with Pierre Bayard’s vision of reading as a “gathering of fragments” (Bayard 83–84).5 This may also be linked with what Bloom calls “creative revisionism”, a phenomenon which allows the clinamen (deviation) process to occur: “The clinamen, or swerve […] is necessarily the central working concept of the theory of Poetic Influence, for what divides each poet from his Poetic Father (and so saves, by division) is an instance of creative revisionism […]” (Bloom 1975, 42). Nabokov created his own definition of what he perceived to be Flaubert’s devices and of their purpose, so that Flaubert’s other uses of “; and” are dismissed in his analysis, while only one, clear Nabokovian definition is retained. This is coherent with Bloom’s vision of creative revisionism: “[…] the new poet himself determines his precursor’s particular law. If a creative interpretation is thus necessarily a misinterpretation, we must accept this apparent absurdity” (Bloom 1975, 43). Unless, as Paul Valéry states in “À propos du Cimetière marin”, there is no true meaning of a text, and therefore no flawed interpretation, so that the more creative the reader is, the richer their interpretation will be:

Quant à l’interprétation de la lettre, je me suis déjà expliqué ailleurs sur ce point ; mais on n’y insistera jamais assez : il n’y a pas de vrai sens d’un texte. […] Une fois publié, un texte est comme un appareil dont chacun peut se servir à sa guise et selon ses moyens : il n’est pas sûr que le constructeur en use mieux qu’un autre.

Nabokov’s use of “; and” also explains the second axis of influence—inspiration leading to exploration. Indeed, while Nabokov appropriates and puts Flaubert’s device to use, he does not use it exactly in the same way as described in his class on Madame Bovary. Nabokov’s “; and” device fits his general style, characterized by more excess and flights of fancy than Flaubert’s. His imaginative drive leads Nabokov to deviate from the device’s original purpose and effectively create a new device, marked by his individuality.

Following the two axes of influence, Nabokov, according to a complex process of continuity and deviation, both highlights his own vision of Flaubert, revealing unknown aspects of the precursor, and establishes his own “exemplary originality” by enacting his “stylistic individuality”.