When it comes to operatic adaptations of literary classics, King Lear stands in a class of its own. This play has deterred some of the most famous musicians of all time. Thus, after pondering over the tempting, yet overwhelming, intricacy of William Shakespeare’s famous double plot,1 composers such as Hector Berlioz, Ernest Bloch, Benjamin Britten, Claude Debussy, Henri Duparc, Edward Elgar, Joseph Haydn, Pietro Mascagni, Giacomo Puccini, Henry Purcell, Giuseppe Verdi or Richard Wagner thought it wiser to withdraw from such an enterprise. As critic Winton Dean stated, “only lesser beings have rushed in, mostly in Italy and France, with results that could have been predicted” (Dean 1964, 163).2

Aribert Reimann3 was perfectly aware of such a specificity when he started working in 1975 with librettist Claus H. Henneberg on a possible libretto for their opera Lear. “I hesitated much, rejected the idea. But I kept on reading the play during the year” (Reimann 1978, 51), the German composer said later. Still, the premiere took place on 9 July 1978 at the Munich National Theatre. It was highly successful. Reimann’s Lear was the achievement of a composer then aged 42, known as a professor of contemporary lieder at the Hamburg Conservatory and piano accompanist for singers such as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. For the first time, an attempt to match Shakespeare’s play on operatic grounds seemed definitely praiseworthy.4 For a long while, numerous Shakespeare critics have tended, in different ways, to single out King Lear from the rest of his plays, although recent criticism is tempted to regard this play as probably the best Shakespeare wrote, along with Hamlet. Some simply wished to “pass this play over, and say nothing about it” (Hazlitt 57), others thought that “auprès de Lear, les autres tragédies nous semblent raisonnables, bien composées, à la mesure de l’homme” (Fluchère 338) or that it was a “Leviathan” (Lamb 33), “Shakespeare’s greatest achievement, but […] not his best play” (Bradley 199), “the most perfect specimen of dramatic poetry existing in the world” (Shelley 134), even “the most tremendous effort of Shakespeare as a poet” (Coleridge 2)…

What follows, however, is not to determine whether King Lear deserves such comments or not. It is rather to examine a way to solve the all-time contradiction lurking between two different art-forms: opera and drama. Undoubtedly, the unusual scope and the intensity of the play make their combination even more difficult. A life-long Shakespeare lover and musical translator, Giuseppe Verdi delivered a grim diagnosis about the feasibility of such an effort. According to him, King Lear is “so vast and intricate that it seems impossible one could make an opera out of it” (Osborne 59). Fortunately, such words of warning did not put an end to Reimann and Henneberg’s project. Let us try to see how these bold artists managed to turn King Lear into an effective opera. More precisely, we will look at the way they solved the four main problems usually faced by any would‑be lyrical adapter of a Shakespeare play.

First of all, the fact that a spoken word is usually much more quickly delivered than a sung word leads to necessary cuts in the original text. As far as action is concerned, what should be left out and what should be kept? Is there a way for composers to speed up lyrical action without betraying or defacing their source of inspiration? Then appears another puzzling problem coming, this time, from the richness and ambiguity of some of Shakespeare’s characters. How did the German pair manage to avoid damaging Shakespeare’s finely sketched characters? What original solutions did they imagine in order to deal with characters such as Lear himself, but also Cordelia, Edgar or Gloucester, for instance? Then, since opera—compared to theatre—seems to offer a wider range of possibilities as far as the use of human voice is concerned (from normal speech to shouts and murmurs, but including also psalmody, monody, accompanied or unaccompanied recitatives, coloraturas, high pitched arias, falsettos, ensembles…), Reimann and Henneberg decided to set up their own scale of emotional expression, as will be detailed in our part 3. But does it work in Lear and how? Finally, opera being an art form with plots and agents that are definitely larger than life, adapting a play on the lyrical stage is a project that has to be tackled with extra precaution. Obviously, with a drama like King Lear, we are also in a land that is bigger than life. Yet it is not exactly the same land: if exaggeration is part of the essence of opera, psychology is usually poor. Therefore, how can such a gap be filled? How is it possible for a composer to take advantage of the melodramatic opportunities to be found in the original text? Should they be left out or re-shaped? And what does it mean when it comes to connecting drama and music? Thus, we will try to show how Reimann and Henneberg achieved a genuine tour de force, not only turning their Lear into an outstanding adaptation of King Lear, but also helping us to understand why some adaptations of Shakespearian plays for opera are successful and others are not.5

Speeding up Shakespeare

Actually, opera and drama are dubious, at times antagonistic, partners since both pull in opposite directions. In the first place, the tempi of theater and opera are totally different. The usual delivery of the spoken word is incomparably quicker than that of a sung word. Thus, a librettist adapting a theatrical masterpiece first has to drastically reduce the play down to a near quarter of its original length (though most productions of Shakespeare’s plays cut the text to some extent), if he does not want his opera to be just as long as the whole of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen and see his audience slumber. If working on King Lear, his task is bound to prove harder as this play is one of the longest ever written by Shakespeare.6 In the prospect of a lyrical performance, minor characters or events must be left out. Thus, for instance, characters such as Burgundy or Oswald are omitted in Reimann’s Lear. Occasionally, whole scenes or even a complete sub-plot have to be sacrificed. But this may simply not do the trick. In 1975, sketching his libretto for Reimann’s Lear, Claus H. Henneberg faced this very problem:

Tout d’abord, je me mis à condenser simplement certains passages du drame, ainsi qu’on le ferait pour une représentation de théâtre parlé, tout en réalisant combien j’enlevais de la vigueur au poème. En outre, il s’avéra que j’obtenais encore un opéra de six heures, même si je ne conservais que les scènes indispensables. (Henneberg 12)

Mere cutting is only one of the means to make up for the slack between two different delivery speeds. It has to be supplemented by a more efficient technique, such as melting several scenes into one. For instance, let us pay attention to the German librettist’s treatment of the two scenes7 where Goneril (I.4, 180–314) then Regan (II.2, 339–499) turn their father out of doors. These scenes are merged together in the opera (I.2, bars 664–918).8 As they stand, these bars concentrate the peak sequences of an action to which Shakespeare devoted half of act I (the quarrel with Goneril) and nearly the whole of act II (the parallel quarrel with Regan). Moreover, they illustrate from another point of view the different speed of action proper to opera and drama. “In the spoken drama, wrote W. H. Auden, the discovery of the mistake can be a slow process and often, indeed, the more gradual it is the greater the dramatic interest is, in a libretto the drama of recognition must be tropically abrupt, […], song cannot walk, it can only jump” (Auden 9).9 These two Shakespeare scenes (I.4, 180–314 and II.2, 339–499) were ill‑suited to opera tempo. Once merged, they offer a better dramatic balance presenting us immediately with two harpies blatantly joining hands in order to deprive of his belongings a “poor, infirm, weak and despised old man” (III.2, 20): their father and former King. Not only are words saved, but the inescapable tragic spell of the whole plot is greatly enhanced in the perspective of an operatic adaptation.

Nevertheless, this device is not free from drawbacks. Much of the interest in these two passages is derived from Shakespeare minutely combining a progressive unfolding of the real nature of his protagonists—scene after scene they are individuated, especially the two sisters—on the one hand, and a steady increase of the dramatic tension on the other. For instance, Shakespeare’s act II, scene 2, shows Lear more and more viciously humiliated by his shameless daughters. Such a gradual destructive process going from the “scared bravado” branded by Harley Granville-Barker as Goneril’s former attitude towards Lear (Granville-Barker 33) to the final decision to cast him out has been left out in the libretto.

I would also like to point out that simultaneity has not exactly the same meaning in a theatre and in an opera house. For instance, Reimann is able, in his opera, to develop together two strongly contrasted scenes (Shakespeare’s IV.2, 17–28 and IV.4, 1–20), when the Bard’s technique consists in suggesting simultaneity rather than actually writing it directly into his plays. In Lear, half the stage represents Albany’s castle and is devoted to the Goneril-Edmund lust scene, while the other half, located near Dover, features Cordelia “as a kind of beneficent Goddess of Nature” (Danby 134) pitying her father’s fate. Vocal lines are entwined, making us jump incessantly from one camp to the other. Moreover, throughout the passage (II.2, bars 147–232) the orchestral texture is progressively penetrated by a sense of impending danger: double-basses roar louder and louder at Cordelia’s entrance, a few bars later threatening sul ponticello violins punctuate her invocation to the “virtues of the earth” (IV.4, 16). Each party seems to keep a watchful eye on the other while forwarding its own pawns. Significantly, Cordelia’s imploring speech, based on King Lear’s IV.4, 15–20, is delivered thus:

Cordelia (near Dover):

All ihr glücklichen Geheimnisse, …

Goneril (in Albany’s castle):

Mein tapferer Edmund, Graf von Gloster! (Shakespeare IV.2, 25)

Cordelia (near Dover):

… ihr unbekannten Heilkräfte der Erde, …

Goneril (in Albany’s castle):

Ich schicke Nachricht über alles,

was diesen vorgeht. (Shakespeare IV.2, 18–19)

Cordelia (near Dover):

… sprieβt unter meinen Tränen hervor,

heilt diesen alten Mann.10

In other words, “while the order of the inner world of feeling is described, the outer order of the political sphere is not forgotten” to quote John F. Danby (Danby 135). In this instance, Reimann and Henneberg not only manage to compress the drama without defacing it, but what was to be implicitly understood in Shakespeare becomes visible in their opera, this being legitimate in the prospect of an operatic adaptation. Immediately effective as it might be, this treatment is not something original. As a matter of fact, Bernd Aloïs Zimmermann, in his opera Die Soldaten (1965), had already used simultaneous scenes.

What is to be done with Shakespeare’s characters?

Another reason for conflict between opera and drama, these two “notoriously unaccommodating bedfellows” (Dean 1965, 75), rests in the nature of the characters themselves. Self-deception, passivity or metaphysical concerns are certainly rich shafts of ore out of which fascinating characters in a novel or a drama can be dug, yet for librettists these dispositions have proved more than once to be quicksands. For example, numerous composers, from early 18th‑century Francesco Gasparini up to 20th-century dodecaphonic Humphrey Searle,11 have considered the workability of a lyric Hamlet. Hack or top librettists, among whom Arrigo Boito whose collaboration with Verdi on Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893) propelled him to the heights of operatic stardom, have penned their versions. Bewitched by the ghost of Hamlet’s father or puzzled by the young prince’s “antic disposition,” none of them has ever reached any sort of success, though some scores are still remembered today, such as Ambroise Thomas’ Hamlet (1868). Adrian Leverkühn, in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, may be right when he says that “music is ambiguity turned as a system” (Mann 1997, 51), yet as far as opera is concerned, this definition seems to be a dead end. Here, what is sung must correspond to dramatic reality, and any kind of distanciation would be out of place.

In this respect, King Lear has much to fear from the industry of would‑be operatic adapters. Undoubtedly, the dramatis personae of the play features characters likely to appeal to any composer. In this category the most prominent figure is Kent. Though a secondary character in the drama, his unquestionable physical courage, his unwavering allegiance to the royal prerogatives, his stubborn desire to protect and serve the King in spite of Lear himself make him fit for the opera-house. Other characters belong to the same group, such as Edmund, though the words sung by this hypocritical Machiavel and Iago’s match in villainy are often lies. Yet deceivers in opera can be aptly depicted by having the orchestral texture at variance with their vocal line. But, unless they are used very cautiously, such devices bring confusion rather than anything else. Quite naturally, the evil sisters, too, belong to this category, since boundless struggle for power is one of the most appealing and pictorial themes on a lyrical stage alongside with passionate love. The history of opera is full of variations on this theme, and, for instance, the daughters’ revengeful duet in Lear (I.2, bars 554–662) has a neo-Wagnerian flavour: it reminds one of the similar Ortrud-Telramund duet in Lohengrin (1850).

Yet not all characters in King Lear are built on this pattern. Thus, Lear, Cordelia, Edgar and Gloucester represent a much stiffer challenge. For instance, how should a composer handle Lear’s evolution in relation to his widely diverging experiences: madness, remorse, despair, submission? What should one do with Gloucester’s desire to keep a foot in each camp up to the third act? Cordelia—the most silent character among the main protagonists (she only has 114 lines and appears in just four scenes)—is sure to force a librettist into desperate measures for even when absent, she looms large in the drama. Her part is what William R. Elton calls “a constant argumentum ex silentio” (Elton 75). A nightmare in terms of operatic translation. When faced with such cruxes, librettists and composers are usually left hopeless and helpless. For instance, Henry Litolff (Le Roi Lear, composed in 1889–1890) omitted all of the Gloucester plot: out went Edmund, Edgar and Gloucester, as well as every scene in Shakespeare in which they appear. In Vito Frazzi’s Re Lear (1939), Cordelia never appears on stage, yet the voice of her ghost—not the ghost itself—is to be heard at the end of the opera. Admittedly, the credibility of an opera libretto rests heavily on its ability to generate extremely stylized climactic situations from which much of the expressive power of the opera itself will be derived. For, as Gary Schmidgall puts it, “music is uniquely capable of accompanying and vitalizing such explosive moments of existential insight. In its impetus toward concentrated and striking expressivity, opera is an epiphanic art-form” (Schmidgall 12). But most main characters in King Lear are endowed with an emphatic vitality that seems to run counter to any stylizing attempt. Definitely larger than life, they are in fact “too huge for the (operatic) stage,” as A. C. Bradley might have said (Bradley 247).

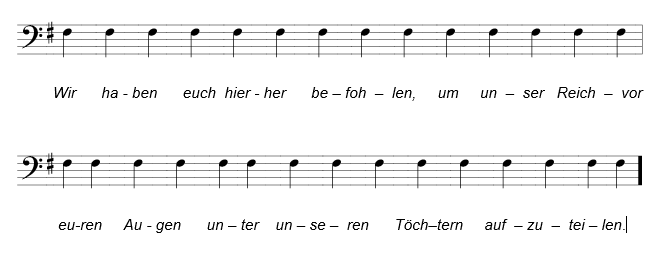

Among other reasons, Reimann’s is a major score—superior to former lyric Lears—because he made no effort to conceal this very contradiction. On the contrary, he fully acknowledged it. Where a sung line would not do justice to a speech, Reimann gave up song and resorted to a particular kind of psalmody. Thus, when Lear announces his intention to divide the kingdom between his three daughters, he does it in the following manner:12

Where mere information is to be provided, Reimann uses the spoken voice, as Gloucester does when reading Edmund’s forged letter (I.1, bars 351–356). In so doing, Reimann follows a path Verdi had already trodden in his Macbeth (created in 1847 and re‑vamped in 1865), when he had Lady Macbeth read her husband’s letter about the witches’ prophecies on stage.

Uttering Shakespeare on the lyrical stage

In order to get away from the usual operatic dead ends likely to turn Shakespeare’s characters into nonentities, Reimann and Henneberg devised a scale of expressive, emotionally focused utterance which expands the traditional span of the lyrical voice and, for instance, includes shouts or murmurs alongside with straight ensembles or arias. This scale of rising emotional intensity—from realistic to operatic—differs substantially from the one devised in his time by Gary Schmidgall and often used as a reference (Schmidgall 1977, 11).

Also, Reimann left aside the still fashionable Wagnerian leitmotiv (which Italian composer Vito Frazzi13 did not) but developed a handful of themes or dodecaphonic series and sometimes superposed them as exemplified by Lear’s death. The old King dies as the dodecaphonic series of the tempest and of Cordelia fade away. In short, every time the German composer felt the limits of the operatic genre jeopardizing his adaptation, he looked for original answers, sometimes in other fields, and tried to adapt them to his medium. In his mind, stage concerns come well ahead of any claims for orthodoxy or originality.

So when dealing with Edgar, Reimann provided his character with a double tessitura. The voice of Gloucester’s son is that of a tenor, yet, in Poor Tom’s guises, he switches to countertenor. This device confirms what Gloucester says (IV.6, 7–8 in King Lear; II.5, bars 391–392 in the opera).14 Thus, downfall from the highest spheres to utter wretchedness is symbolically and ironically15 translated in Reimann’s scenic dramaturgy by switching to the upper ranges of the human voice. Significantly, when challenging his brother Edmund, the future King resumes his former tessitura.

Contrariwise, Lear—another outcast—remains a baritone throughout. Though the evil sisters tend to consider the parting of the kingdom and Lear’s old age as sufficient grounds for disregarding royal prerogatives,16 he never did give up his kingship. According to Regan and Goneril, King Lear should be replaced by a man from their party. Such contempt for the allegiance to the King’s body and, generally speaking, disregard for the law at the head of the state, give license for subjects to break the law.17 Significantly, Reimann and Henneberg did not cut out the episode (III.7, 71–81) in which a servant, revolted by arbitrary cruelty, feels compelled to put an end to Cornwall’s and Regan’s deeds and draws his sword against the duke (II.1, bars 94–102) to enforce respect for the law of Nature. While his very father and his brother Edmund do not recognize Edgar, Lear—even when roving madly—is still considered as the only embodiment of royal legitimacy in the kingdom, at least by some of the characters. Consequently, his tessitura remains the same while Edgar’s does not.

Comparatively, Reimann’s treatment of Cordelia seems somewhat unfortunate. Though Henneberg boasted that, in his libretto, he paid more attention to the character of Cordelia than Shakespeare did,18 we may not agree. Firstly, she is allotted what the German librettist calls an aria (Henneberg 13) when her line “mein Vorsatz bleist, ich werde schweigen” (I.2, bars 59–60 echoing Shakespeare’s “Love, and be silent” (I.1, 62) just seemed to have paved the way for a subtler account of a character who “absent is, perhaps, as powerful as […] present” (Elton 75). Furthermore, Reimann’s much stressed idea of giving her a dodecaphonic serie, which is the exact inversion of Edgar’s, is highly debatable as inverted series can logically indicate proximity as well as difference. No doubt Cordelia and Edgar have much in common: in Victor Séméladis’s opera Cordélia (1854), for instance, they are engaged. Both are young and represent the younger generation confronted with the reactions of blind fathers. They are outcasts—though unlike Cordelia, Edgar must hide himself—and real embodiments of Danby’s tragic axiom: “Goodness needs a community of goodness. And that is unlikely to be found in the world” (Danby 166). In King Lear, the initial partition of the kingdom has undermined the very foundations of kingship. This degeneration has opened the doors to Machiavellianism without any possible return. Significantly, at the end of the play, Albany, the last representative of the royal family, offers Kent and Edgar the possibility of sharing with him the reins of power. Kent refuses, while Edgar’s answer is a rather bitter one.19 In Lear, this passage is omitted, the opera ending with Lear’s despair, the body of dead Cordelia at his feet. “Goodness needs a community of goodness. And that is unlikely to be found in the world.”

In Reimann’s mind, a musical proof of the proximity of both characters was more effective than mere lines added to the libretto. Structurally, this is well thought out, yet, dramatically, the process does not take into account a huge difference in the temper of the two Shakespearian protagonists. “Imperfection, instability, or confusion will lay everyman open to the necessity of acting more parts than one, until the order is restored. Duplicity will be enjoined on [Edgar] as a virtue” (Danby 171). But duplicity cannot be blamed on Cordelia. Her early voiced resolution to “love according to (her) bond no more nor less” (I.1, 92–93) is her motto throughout the play. Edgar’s series of social and strategic metamorphoses are unparalleled in the character of Cordelia.

Cordelia: We are not the first

Who, with best meaning have incurred the worst.

For thee, oppressed King, I am cast down;

Myself could else outfrown false Fortune’s frown.

Shall we not see these daughters and these sisters?

King Lear: No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison;

We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage (V.3, 3–9).

Held prisoners by the evil sisters, she recklessly faces a very likely death sentence, while the old King tries to evade his fate. Unlike Edgar, she never conceals anything, either herself or her thoughts. She will die; he will become king.

Reshuffling the Shakespearian cards

A fourth major reason for the precarious cohabitation between opera and theatre is their diverging scopes. Indeed, opera is an inflationary art form, it requires extraordinary plots and agents from its demiurges. Thus, resorting to song as a medium for communication between the characters may appear partly justified. Seventy years ago, W. H. Auden summed up the requirements of the genre:

The librettist need never bother his head, as the dramatist must, about probability […]. A good libretto plot is a melodrama in both the strict and the conventional sense of the word; it offers as many opportunities as possible for the characters to be swept off their feet by placing them in situations which are too tragic or too fantastic for “words”. (Auden 9)

Thus, in Lear, we find most melodramatic elements coming from Shakespeare’s text carefully reassessed. For instance, in the play, both Regan and Edmund are led off-stage where they die while Goneril stabs herself in some private room unseen from the audience. In the opera, on the contrary, the three of them die on stage and within a few minutes: Regan, Edmund and Goneril die respectively at bars 745, 768 and 780. This triple death gives Reimann an opportunity to develop a thrilling death-song for Goneril whose atmosphere evokes that of an execution, barely supported as it is by a slow and regular roll of timpani:

Goneril: Er starb, so sterbe auch ich.

Mir helfen keine Götter mehr.

Leib und Seele habe ich selbst zu richten.

Komm, Tod und nimm mich,

die dir so reiche Ernte brachte…20

These lines—II.7, bars 768–782—are a Reimann-Henneberg coinage not to be found in Shakespeare’s text.

Gloucester’s blinding goes through a similar treatment. In his play, Shakespeare has Cornwall alone applying his eye-for-eye conception of justice, even if “pressing poetic justice still further, Regan urges that both eyes be extinguished” (Elton 107) and then kills the revolted servant who has deadly wounded her husband. In Reimann’s opera, Regan herself has an active part in the gouging out of the Earl’s eyes. Of course, the symbolic value of the ignominious deed is greatly enhanced by having a female hand directly partaking in it. But mostly, it provides a cogent justification for the ensuing dialogue—a piece of sheer drama: II.1, bars 111–134—in which the real nature of Edmund is unfolded to his father who weeps tears of blood as Regan hysterically laughs and yells. Blinding Gloucester, she metaphorically helps him to open his eyes to reality. A librettist’s task is to seek or create such crude contrasts.

Yet one ought to bear in mind that, as Winton Dean observes, “a good libretto is a scaffold, not an independent structure. To compare it with the play[-text] is irrelevant and unfair; if there is to be a comparison, it must be between the play and the whole opera, music and words together,” preferably both on a stage (Dean 1968, 88). The poetry of opera is essentially to be found in music, words being some sort of springboards. When the two perfectly lock together, they can create “melodramatic opportunities” like the unfolding of Edmund’s real nature. These “melodramatic opportunities” are the very stuff opera is made of. They should break loose from the narrative network and rise to a clearly universal significance. Thus, much of the impressive strength of Reimann’s score rests on such “epiphanies” as Gary Schmidgall would call them, such as the storm scene (I, interlude 2, bars 38–134) and the Dover cliff scene (II.5, bars 374–455). Effective as they might be, these scenes still need a link to connect them together. As Benjamin Britten’s librettist for The Rape of Lucretia (1946), Ronald Duncan puts it:

There are points in a libretto where the drama must unfold, proceed from one situation to another. These developments must be heard and understood […]. Other moments in the drama might give opportunity for a situation to be held or sustained […]. I found I was underestimating the power of music to express precise emotion and characterizations, but later relied on its contribution to the actual statement of the drama. (Duncan 61–62)

Following in Alban Berg’s footsteps (the opera Wozzeck was created in 1925), Reimann and Henneberg focused their libretto on the illustration of one individual and exemplary tragedy. To reduce Shakespeare’s polyphonic drama to its essential simplicity and concentrate on Lear’s destiny implied a radical clearing out of most political or social statements of the play. To the intricate Shakespearian plot, Reimann and Henneberg substituted a bare trajectory: exposition, peripetia, catastrophe. Summarized, their libretto yields the following synopsis:

-

1st part: partition of the kingdom and Lear’s decisions. Lear’s humiliation. Confrontation between genuine (Lear’s) and feigned (Edgar-Tom’s) forms of madness;

-

2nd part: excesses of Evil confronted with momentary triumph of Virtue eventually leading to final catastrophe.

Indeed, with Reimann and Henneberg, we realize that a libretto is a distinct literary form, “not a mere drama that is then set to music. It should be a drama which is written for music. This distinction describes the form itself” (Duncan 59).

Conclusion: reasons to hope

Therefore, condensing King Lear into an effective libretto is undoubtedly a very complex undertaking. Yet somehow the very nature of Shakespeare’s dramaturgy does not seem completely antagonistic with the requirements of such an opera-text. Roughly speaking, a Shakespearian play can never be reduced to the sole meaning of its plot or even to the quality of its poetry. Thus, in spite of the inherent difficulties or impossibilities mentioned above, a librettist pondering over the adaptation of a Shakespearian play is likely to find his project and the spirit of the play congenial on three points at least.

Let us remember that Shakespeare’s plays were not meant to be printed or read but actually performed on a stage. As critic Andrew Gurr aptly stated:

The fundamental principle they all held, which underlies all consideration of the body of literature they produced, is that their works were written for the stage, for the playing companies, and the durability of print was a secondary consideration, the sort of bonus that would normally only come in the wake of a successful presentation in the company repertoire. (Gurr 22–23)

Now, as far as opera is concerned, few people, even among music lovers, can read a score at sight. Therefore, just like Shakespeare’s plays, opera mainly exists when performed. This is a first common point.

Although it was not a concern at the time of Shakespeare’s plays, let us point out that what we may consider today like apparent improbability seems, at first sight, to be a snare sometimes threatening his plots. For instance, Lear’s initial partition of his kingdom probably appears to most modern readers as too emphatic, a somewhat far-fetched idea lacking credibility.21 Yet this seems to be essentially a problem when reading the plays. On stage, the author’s superior handling of his sources systematically blurs this aspect of his dramaturgy. Moreover, his most puzzling or depraved characters can usually be related to a historical or legendary trend, thus granting a credibility to their actions on stage. Lear’s idea of a “Triall of Love”—as Raphael Holinshed (one of Shakespeare’s sources) called it—may seem to us psychologically improbable or too emphatic, yet it is recorded in several chronicles of the time. Opera and Shakespeare’s plays may have diverging scopes, nevertheless they share a second specificity: emphatic vitality.

Finally, turning a play into a libretto implies, above all, drastic cuts in the original text. As we have seen, difficulties arise when one has to select the actual passages or characters to be omitted. Yet, by interlarding his plots with independent themes or topos,22 Shakespeare fortuitously provided such a selection for the benefit of his future operatic adapters, though he obviously did not intend to do so. In the prospect of a libretto, these insertions can be removed without damaging the general sense of the play too much. Furthermore, this impoverishment of the play is sure to be concealed, in the opera, by the shifted poetic focus—from words to music—inherent to any adaptation of this kind.23 This specificity of Shakespeare’s dramaturgy cannot solve every problem a librettist may encounter. Yet, as such, it shows that, in essence, opera and Shakespearean drama are not necessarily antagonistic genres. Or, as composer of Béatrice et Bénédict (1862, an opera inspired by Much Ado about Nothing) Hector Berlioz said:

Ce n’est pas qu’il soit possible de transformer un drame quelconque en opéra sans le modifier, le déranger le gâter plus ou moins. Je le sais. Mais il y a tant de manières intelligentes de faire ce travail profanateur imposé par les exigences de la musique. (Berlioz 1)

How this “work of profanation”—reducing Shakespeare’s five acts and twenty-four scenes to two parts, five interludes and eleven scenes—was carried out by Reimann and Henneberg will be judged from our Annex 3 below. But, at the end of this paper and in a last attempt to illustrate Reimann and Henneberg’s approach to Shakespeare, let us mention, for example, that most of the Fool’s lines in Lear are not derived from Shakespeare but from an anonymous sixteenth-century text, Die Ballade vom König Leir und seinen drei Töchtern, as pointed out by Henneberg himself.24 In a somehow similar and surprising way, when Reimann was asked why he insisted on having this very character played by an actor and not a singer, something very unusual in an opera house, he boasted: “C’est justement parce que cela ne se fait pas, le Fou reste à l’écart” (Reimann 2022, 133). With Lear, the audacious German pair achieved a genuine tour de force no other opera creators came close to. Never wavering when they thought it necessary to go against current uses or aesthetics, they managed to be faithful to Shakespeare, while half of the words in their libretto did not come from his King Lear (Candoni 77). One of the main reasons for their success probably lies in this capacity to go recklessly against the grain, just like Shakespeare did. “Le[s] fou[s] reste[nt] à l’écart.”