Introduction

The term transvestigation is a relatively new coinage referring to a specific socio-discursive phenomenon as it is platformed on various social media. Transvestigations are characterized by users referring to a person’s physiological features and behaviours as indicative of their transgender status. These primarily erroneous assignations of a person’s secret transgender status are often directed at celebrities and politicians, though they are also directed at fictional – including animated – characters from popular media and people in the transvestigator’s offline life. By focusing on rudimentary assumptions of sexed physiological difference and hegemonic expectations of gendered behaviours, transvestigators deploy cis- normative ideological framing and appeal to pseudo-scientific expertise to legitimize transphobia and conspiratorial thinking.

Despite the new nomenclature, these practices are not at all new on social media and in popular media cultures, more generally. Reality shows like There’s Something About Miriam (2004) and the infamous ‘Female or Shemale’ segment aired on RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009 –2023) have relied on the same tropes of transgender women’s trickery and misogynist examinations of women’s bodies. Indeed, even before the term transvestigation was coined, conspiracies surrounding some – primarily celebrity or otherwise publicly known – women’s secret transgender status have been platformed in various quarters. For example, Michelle Obama has long been victim of body-shaming for her purportedly masculine features – like the shape of her arms and shoulders – and unfounded allegations of her husband’s sexual activity with other men.1 These long-standing transvestigation discourses, albeit known by other names, highlight the intersectional nature of the hate and victimization on which they are built. Transphobia, homophobia, misogyny, and racism are enmeshed – albeit in various and variable permutations – in order to entertain others and/or direct the critique of other’s bodies as evidence of a social deception.

What is specific to social media transvestigations, as opposed to similar practices historically platformed in popular media, is the conspiratorial framing that underpins them. The conspiratorial basis of transvestigation discourses is threefold: 1) transgender ubiquity, 2) the threat of social contagion, and 3) the framing of transgender people as belonging to some elite cabal seeking to enslave the world’s cisgender population at large. Again, these conspiracies build on long-standing fascist ideologies. That is, antisemitic and homophobic conspiracies of the 20th century were predicated on similar premises (see Kerl, 2022). That these have found a public resurgence among the rising neo-fascism platformed on today’s social mediascape is unsurprising. Indeed, that they are now deployed against a new target is indicative of a shift in the locus of attention for reactionary politics and its associated socio-legal discourses in recent years.

This paper examines the manifestation of transvestigations on social media – focusing on posts from X (formerly known as Twitter) and Instagram – and their relationship with contemporary political and techno-discursive formations. First, I argue that transvestigations contract some mutuality with offline political discourses in the United Kingdom (UK) and United States (USA), which similarly rely on pre-occupations with sexed bodies and work to reify conspiracies of social contagion. Second, I argue that the techno-discursive properties of social media interaction and its mimetic antagonism render the distinction between transphobia and (potentially anti-transphobic) trolling a near impossible task. This paper therefore critiques: (1) how social media and its users discursively (re)construct a world without distinction between authenticity and inauthenticity2, and (2) the mutually constitutive relationship this indeterminably (in)authentic mediascape contracts with real- world politics. In doing so, I seek to highlight the infeasibility of social reform in these contextual conditions. In an age of significant and ever-increasing societal transphobia, this paper therefore seeks to provoke critical conversations about media literacy and the role of social media in reproducing, reinforcing, and resisting movements to hegemonize hate.

1. An ABC of mediatized transphobia

In this paper, I focus on three core elements of transphobia as it is currently mediatized: antagonism, bigotry, and conspiracy. I argue that this ABC of transphobia represents the building blocks of the so-called ‘gender-critical’ narratives that are embedded in some of the neo-fascist ideologies increasingly platformed on social media and that are reflected in reactionary politico-legal shifts in the West.

Gender-critical ideologies are largely predicated on an antagonistic positioning between sex, gender, and sexuality (Webster, 2023). Primarily, this antagonism is constructed vis-à-vis the intersectional experience of womanhood, wherein the experience, safety, and rights of cisgender women – and, often, specifically cisgender lesbians – are positioned as conflicting with those of transgender women (see Webster, 2022). Whilst there has been evidence in the past to suggest that the majority of cisgender women – including those identifying as lesbian or otherwise sexually and/or romantically attracted to other women (Curtice et al. 2019) – are supportive of transgender recognition, vocal minorities in various mediated spaces have sought to perpetuate this ideological and experiential antagonism. On social media, X (the platform formerly known as Twitter) is perhaps the platform most readily associated with the mediatization of these gender-critical voices and narratives. Given that antagonism is arguably a long-standing communicative norm on social media (Farkas et al., 2018), and X/Twitter, in particular (cf. Evolvi 2019; Jane 2017), its use in the articulation of transphobic antagonism is no real surprise. However, since 2019, transphobia on Twitter – and other social media platforms – has gained significant visibility and traction. Celebrities and politicians past and present have espoused their own brands of transphobia, whether by posting their own content or supporting the content of individuals and organisations that seek to falsely pit cisgender and transgender women against one another (see Gwenffrewi 2022; Ryan 2022). Moreover, the platform chose to remove protections for transgender people from its hateful conduct policy (Yang 2023). It is therefore also, perhaps, unsurprising that positive attitudes towards transgender people have significantly decreased year-on-year since earlier polls (Billson 2023). And these shifts have had great impact in real-world politics. In the USA, legislative and policy changes have variably been called for – and, in several instances, passed – that reify the antagonism between cisgender and transgender women in the domains of education, healthcare, and sports (Funakoshi & Raychaudhuri 2023). In the UK, this antagonistic positioning has been deployed in policy changes on prisoner placement and in debates over overarching equality legislation (Webster 2023). As such, though underpinned by a gender-critical ideological fiction, the antagonism between gender, sex, and sexuality is a key feature of current articulations of mediatized transphobia.

The bigotry of present-day transphobia is grounded in a cis-hetero-patriarchal hegemony, comprising sex essentialism, compulsory heterosexuality, and male supremacy. As Erspamer (1997: 153) astutely notes: ‘[bigots] must oppose all those who contradict their “single Supreme”, their principle of unitary consciousness’. Indeed, Erspamer’s equation of overt antisemitic bigotry and the more covert bigotry of liberal tolerance is directly analogous to the current mediatization of transphobic bigotry. For example, overt transphobia can be found in the recent sloganeering around transgender women’s inherently predatory nature, including their victimization of women and children. Whilst entirely unfounded, these claims have also been deployed in the legitimization of the politico-legal changes discussed above. Despite ongoing discourses of transphobia from other far-right LGB groups (e.g. LGB Alliance, Gays Against Groomers), these narratives often coincide with parallel narratives that conflate trans identities with drag performance and which also refer to other gender, romantic, and sexual minorities as paedophiles or otherwise as sexual predators. Much of this is also platformed on social media, by groups like Libs of TikTok, leading to multiple platforms banning the use of the term groomers to refer to LGBTQ+ people (Drennen 2022). More covert transphobia – or, at least, that which is perceived as less extreme – can also be found in similar quarters. For example, the very notion that gender-critical and trans-affirming views have equal moral and intellectual worth based solely on an unwavering – and flawed – commitment to the ideological bounds of democracy (cf. Webster 2023) is evocative of Erspamer’s critique of tolerance. In the UK, this has been repeatedly evidenced in the domain of politics and education, including in the passing of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, which saw 8 of 26 public evidence submissions variably reference this equivalence, including gender-critical beliefs (Ahmed, 2021; Stock, 2021), ‘transgender ideology’ (Biggar 2021), ‘transgender Orthodoxy’ (Kaufmann 2021), or ‘transphobia row’ (Durham Students’ Union 2021), in their justification for the bill to be passed. Similar are calls for the creation of a ‘third space’ in service provision (e.g. Lamb Tod 2018) and guidance that encourages educators to misgender pupils and out them to their parents (Hunte 2023), which are legitimized as a solution that protects cisgender women and children from perceived threats whilst also recognizing transgender identities. Such positions evoke Erspamer’s (1997: 152) narrative of compelling the outsider to ‘restrict themselves to “officially” sanctioned discursive formations’. As such, whilst there are contextual nuances unique to today’s transphobic bigotry, such mediatized discourses bear stark similarities to historical fascist bigotries, particularly with regards homophobia and racism.

Identity with historical – and ongoing – antisemitism and homophobia is as prevalent in the conspiratorial underpinning of transphobia as with the manifestations of its bigotry. The parallels between transphobia and homophobia are perhaps most easily identified. For example, the legitimization of new bills and guidance surrounding the teaching of transgender identities – and teaching by transgender educators – in both the USA and the UK are an exact replica of the ideology underpinning ‘Section 28’ (Local Government Act [1988]) in 1980s Britain. This conspiracy of social contagion via education in historical homophobic discourse directly correlates with contemporary anxieties surrounding viral contagion of HIV/AIDS (Haydon and Scraton 2002). This same confluence of medical discourse and a social contagion threatening children can be seen in conspiracies of ‘rapid onset gender dysphoria (ROGD)’, which transphobes claim is a symptom of transgender visibility (see Ashley 2022). Ironically, such transphobic discourses are arguably reliant on a manifestation of the earlier described covert liberal transphobia, with proponents of banning gender-affirming care for transgender children and young people citing a prevention of gay and lesbian erasure. That is, gender-affirming care for transgender children and young people will force those who would otherwise identify as either gay or lesbian to transition in order to ‘fit in’ with a homophobic transgender zeitgeist. These conspiracies are even legitimized in – albeit significantly methodologically flawed and evidently aligned with so-called ‘gender critical’ ideology – academic literature (see Littman 2018). The logical conclusion to this social contagion conspiracy, then, is the ubiquity of transgender identities and the wholesale replacement of otherwise gender-nonconforming LGB identities. This is, of course, patently untrue. But this conspiratorial framing also taps into some kind of transgender scheme to amend the social order in one way or another. Indeed, although the intersecting conspiracies of homophobia and transphobia are seemingly obvious, the re-appropriation of antisemitic conspiracies in narratives of transgender ubiquity is perhaps more subtle. For example, a particularly common (neo-)fascist trope is the conspiracy of a ‘slave-like new world order’ driven by a Jewish elite and their otherwise leftist co-conspirators (Lamy 1997: 106). I argue that it is exactly this parallelism with antisemitic conspiracy that is simultaneously the most dangerous and most ridiculous foundation of transvestigations as platformed online. It is the discursive manifestation of a transgender ‘new world order’ conspiracy that most explicitly calls into question the authenticity of transvestigations as what one might call ‘authentic’ hate. Indeed, the well-evidenced neo-fascist pre- occupation with disinformation and conspiracy, coupled with a consistent engagement with social media for propagating such narratives, relies on a re-deployment of historical conspiracies to stoke fear and legitimize ‘authentic’ bigotry. I argue that these very contextual conditions – of neo-fascist propensities for disinformation and the affordances of social media –make it impossible to determine the authenticity of these discursive manifestations of transphobia as neo-fascist conspiracy, as opposed to a unique form of (potentially anti-fascist) trolling.

In the age of social media’s attention-industrial complex, the impact of mediatized transphobia is far-reaching. That is, it the transphobia platformed on social media does not occur in a digital vacuum. Rather, it is evident that social media manifestations of transphobia are largely inextricable from the ‘real-world transphobia’ evidenced in recent social, political, and legal changes in the UK and USA. This paper therefore examines transvestigations as a socio-discursive phenomenon that exists in a mutually constitutive relationship with offline structures of increasing structural inequality.

2. Examining transvestigations as a socio-discursive phenomenon

The platforming of gender-critical ideology on social media is nothing new. Renowned for their connection with transphobia and gender-critical discourses are X/Twitter and Mumsnet (Pearce et al. 2020). Other transphobic discourses have notably been platformed elsewhere (see, for example, Thach et al., 2022). However, the ‘transvestigation’ phenomenon has surfaced on most major platforms, including X/Twitter, Reddit, YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. I analyse in this paper 26 instances of ‘transvestigation’ discourses as platformed on X/Twitter and Instagram. These data were selected via platform-internal searches for the terms transvestigation and transvestigations. Engagement with these search results in turn led to the identification of new key terms and phrases within this conspiratorial lexicon, including EGI (or, elite gender inversion), and of responses to such posts in the form of both satire and conspiratorial solidarity. I recognize that the contextual nuances of a platforms’ affordances, its users’ engagement, and its platform-internal conditions directly influence how discourses are manifested. This paper focuses on the general structural conditions of today’s social mediascape, which prioritises attention and antagonism, that render the authenticity of transvestigation discourses and their conspiratorial underpinnings indeterminable. As such, I do not argue for or seek to identify differences in the manifestation of such discourses across and between platforms. Instead, I focus on the unifying features of transvestigations as a socio-discursive phenomenon that spans both transphobia and trolling.

Whilst I rely on a broadly interdisciplinary approach to critical media studies, I primarily draw from socio-cognitive discourse studies (e.g. van Dijk 2009) as a methodological approach and theoretical framework. In so doing, I rely on a tripartite theoretical and analytical structure. At the theoretical macro-level, there are the largely unchanging structural conditions that variably enable and constrain the ways in which we can go on in the world. These are analysable at varying scales, including the political- economic conditions of the offline world (within which the online world is embedded), the prevailing conditions of social media communication in an age wherein it is inextricable from our daily lives, or the local conditions of a specific platform and its internal techno- social ecosystem. At the micro-level, there are the discursive manifestations of our experiences, ideas, values, and beliefs. On social media, these are variably analysable as the text, images, audio-visual content, and meta-communicative functions (e.g. likes, shares, follower/friend connections) that are produced, distributed, and consumed in social media interactions. It is at the meso-level of cognition – of interpretation and construal – that I argue the trouble with transvestigations occurs. Cognition is theorized as a mediatory process bridging macro-level structures and micro-level discourse. However, because the prevailing structures of today’s attention-industrial complex broadly encompasses norms of disinformation, the radicalization of political ideology, and extreme antagonism, it calls into question how users’ discursive interactions interact with those structures. That is, do discourses authentically reflect the social structures most directly associated with their linguistic content (i.e. an increasing societal transphobia)? Or, do they represent an interpretation of the context’s communicative function (i.e. disingenuous communication, disinformation, and antagonism)? Indeed, given that the relationship between discourse and society is mutually constitutive and therefore bi-directional, (how far) do transvestigation discourses reify societal transphobia and/or the indeterminable authenticity of social media communication? In this paper, I primarily argue for the indeterminacy of transvestigations as an authentic discursive manifestation of transphobia. I also argue, then, that the interplay between transvestigation discourses, users’ responses to them, and authentic examples of transphobia in both online and offline spheres, renders this indeterminacy of its status as an authentically transphobic discourse a moot point. Rather, I contend that it is exactly the mutual reinforcement of online and offline communicative practices as indeterminably authentic in contexts of hate that should provoke us – as scholars, activists, and global citizens alike – to reassess the role social media play in reproducing, resisting, and reinforcing socio-structural inequalities.

3. Discursive codes and online-offline mutuality

A basic textual analysis unveils discursive codes that are both commonly shared among transvestigation posts and shared with offline politicking around transgender identities in the USA and the UK. I focus here on the pre-occupation with sexed physiology – including musculoskeletal features and external sex characteristics – and false appeals to scientific expertise as a legitimization strategy. From these features, I argue that transvestigation discourses online share features with offline political discourses in their discursive manifestations of transphobia. I also discuss some coinages specific to transvestigation discourses that highlight their conspiratorial underpinning and indeterminable authenticity.

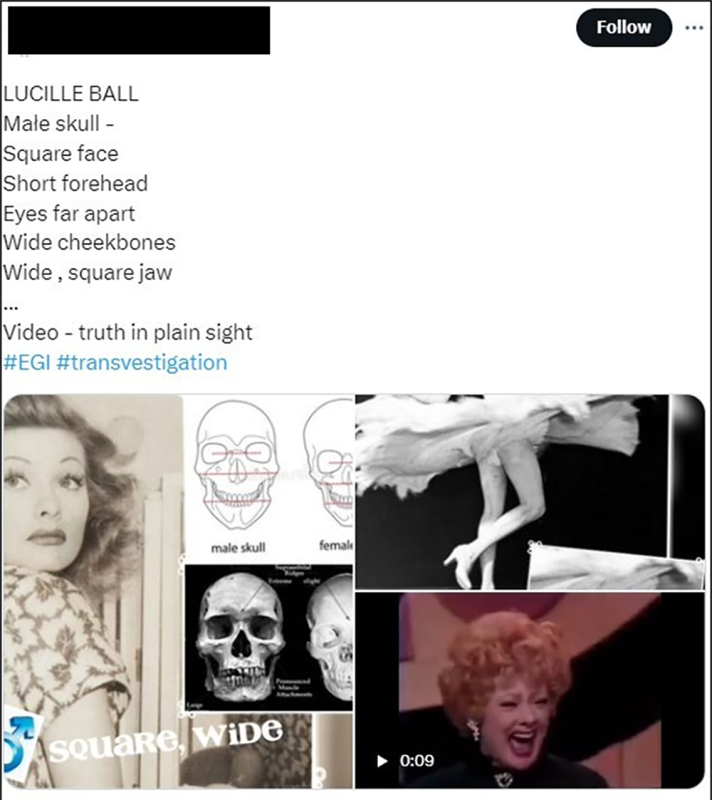

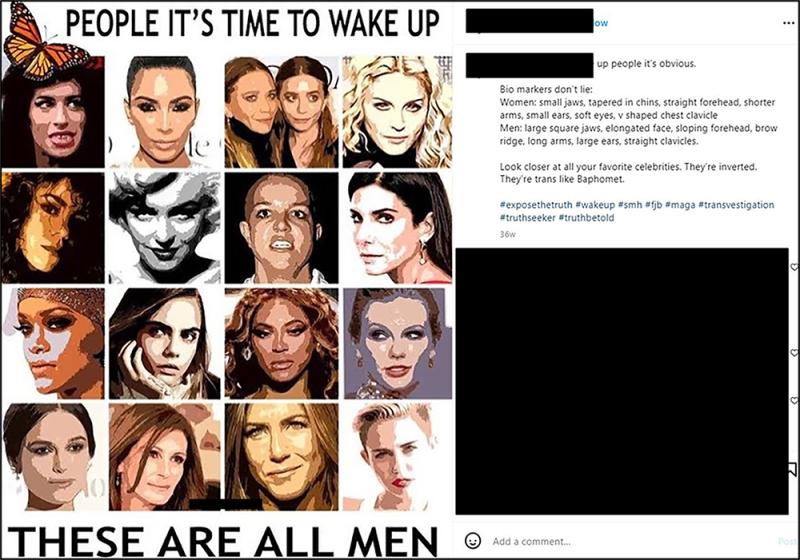

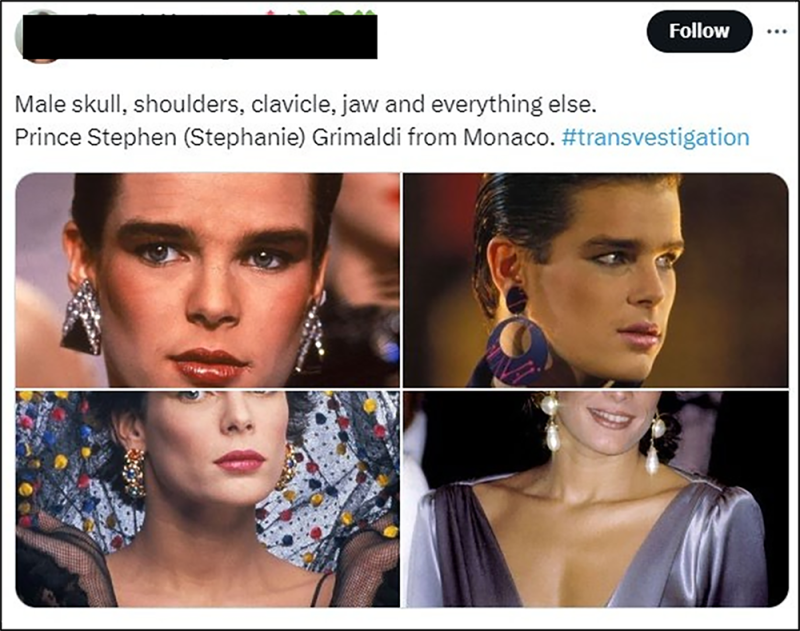

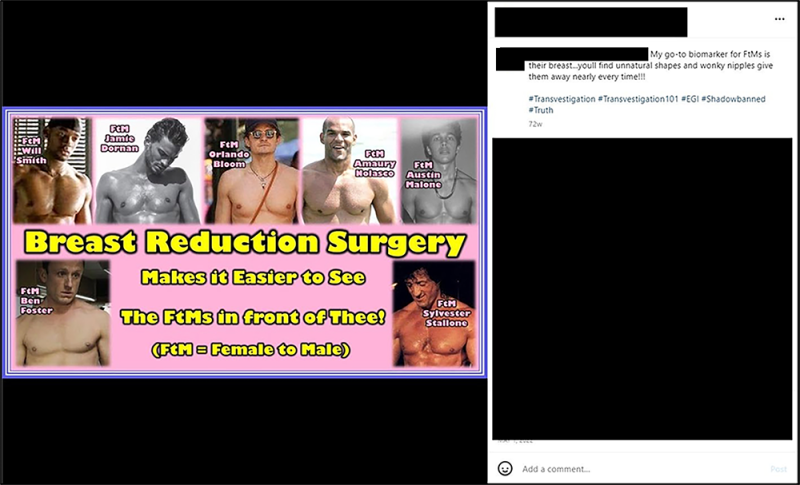

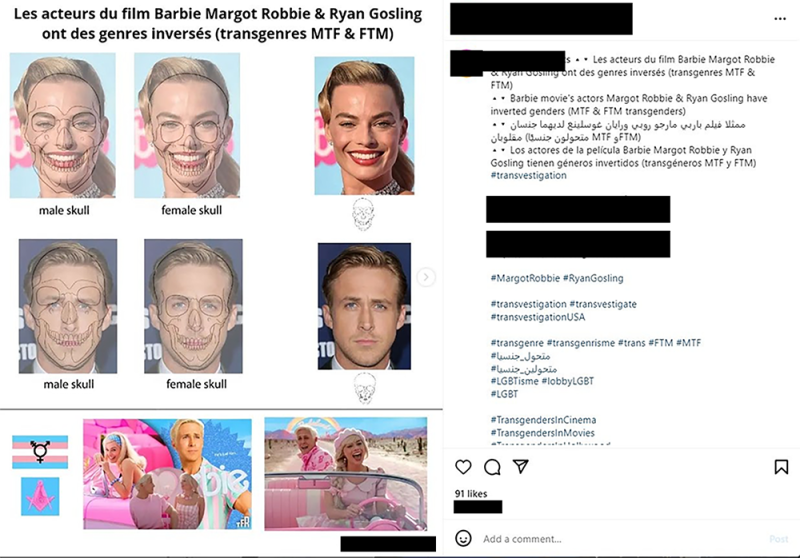

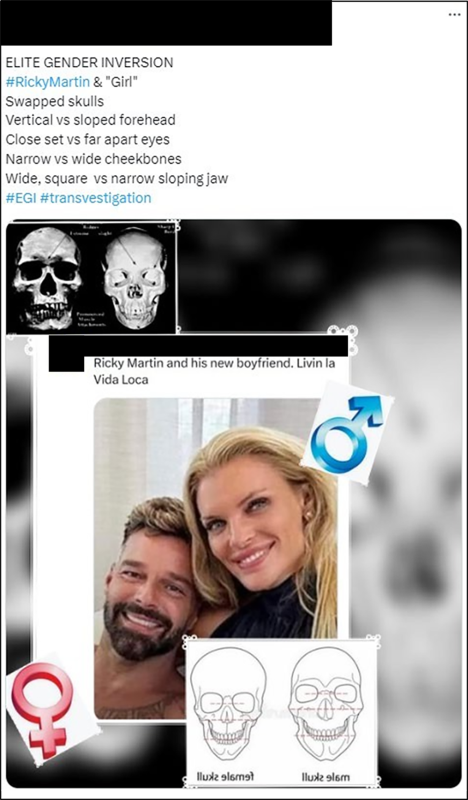

There is a significant focus on the size, shape, and spatiality of a person’s musculoskeletal features in transvestigation discourses. Tranvestigators often reference the skull and the placement or shape of facial features as a purportedly fool-proof and consistent means of identifying an individual’s sex as assigned at birth (examples 1-2). Other examples also focus on the size and shape of specific body parts (examples 3-4). Some of these examples appropriate rudimentary means of identifying the sex of skulls and/or skeletons, which rely on averaged measurements and do not consistently account for what bodies would look like with muscle, flesh, hair, and clothing (cf. University of Sheffield 2023).

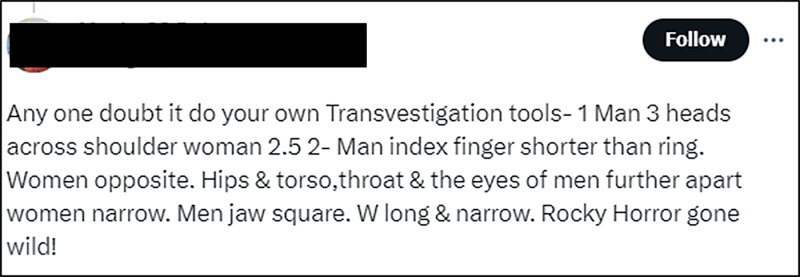

Again, other examples deviate from this and make use of completely arbitrary measurements for sex distinction that are reminiscent of children’s tall tales and nonsense ‘folk’ knowledge, such as the number of heads that should fit within a person’s shoulder span or the relative length of their index and middle finger (example 5). The logical fallacy – argumentum ab auctoritate, or argument from authority – of uncritically appealing to science and folk knowledge is a means of legitimizing the assignation of (secretive) transgender status to the person under analysis, positioning the user posting the content as an expert. Indeed, this is reinforced in those posts that seek to instruct others on how to engage in transvestigations (examples 5-6). Despite the ridiculousness of these claims, they are by no means harmless. Aside from the transphobia (and, most often, misogyny) inherent in pejoratively questioning a person’s sex assigned at birth with reference only to physical features, these discourses bear more than a passing resemblance to historical applications of pseudo-science to violent ends, which used physiological features to classify individuals as less than, other, or otherwise undesirable (e.g. phrenology; eugenics).

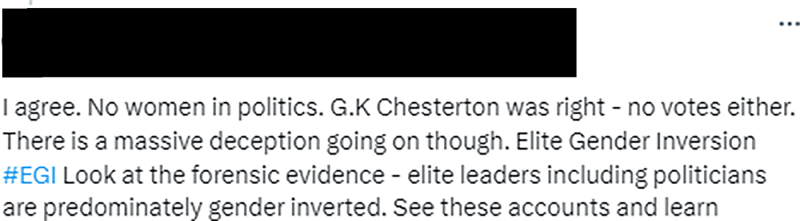

Example 1. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 2. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 3. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

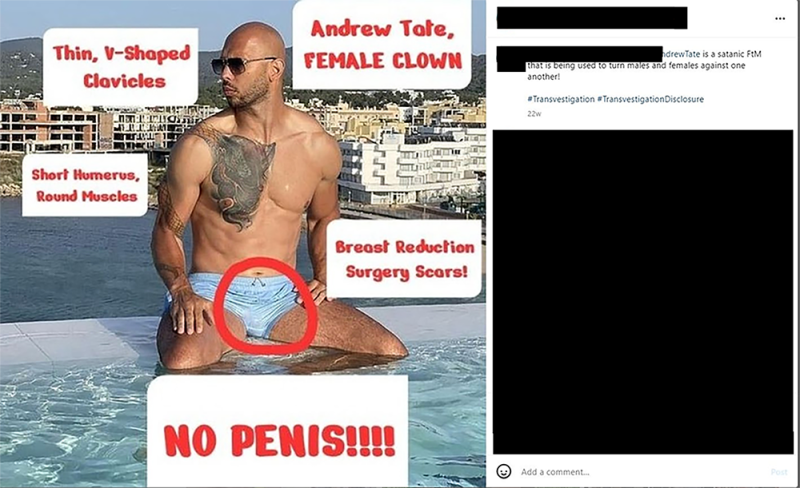

Example 4. Retrieved from Instagram.

Example 5. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

As can be gleaned from the above examples, visual accompaniments range from the obvious to the outlandish. With reference to the former, there is some pre-occupation with the (in)visibility of genitals or secondary sex characteristics as an indicator of a person’s sex (examples 6-7). The latter, then, use bizarre image overlays and other symbols to visually demonstrate the sexed shapes and measurements described in the above paragraph (examples 8-9). A pre- occupation with genitals is perhaps unsurprising, given that a common transphobic trope surrounds the concept of genital reconfiguration – or lack thereof – and that gender-critical discourse is often underpinned by the threat of the ‘physiologically intact’ transwoman-as- predator. As such, whilst the examples appear ridiculous and can be easily explained by such concepts as lighting, dress, pose, and intentional editing, they do serve to reinforce existing transphobic ideologies. The more bizarre use of visual overlays (i.e. drawings of skulls, spines, and pelvises) and symbols indicating spatiality in the musculo-skeletal structure, then, simply serve to reinforce the logical fallacy of transvestigations’ appeal to authority. Again, this is reinforced by pseudo-tutorials on how to apply such investigative tools (example 10), which further construct an expert positioning among some users within transvestigation discourses.

Example 6. Retrieved from Instagram.

Example 7. Retrieved from Instagram.

Example 8. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 9. Retrieved from Instagram.

Example 10. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Whilst many of these posts merely allude to a conspiracy of transgender ubiquity, particularly among celebrities, others explicitly name it. These range from the simplistic and explicit phrasing of ‘illuminati trannies are everywhere’ and similar constructions (example 11) to more obscure references invoking other conspiratorial discourses (examples 12-20). Coinages like ‘elite gender inversion’ and ‘[the] wonky eye’ take the conspiracy of social contagion implied in other posts to greater lengths. Specific reference to ‘elites’ – in the form of celebrities and politicians – as somehow inverted and otherwise in a position of power over others is evocative of antisemitic conspiracies of a new world order (cf. Lamy 1997). A pre- occupation with eyes, as can be seen in other examples above, and a focus on ‘[the] wonky eye’ arguably also invoke similar conspiratorial discourses. For example, the conspiracy of the ‘Illuminati’, which is also oft-associated with antisemitism (see Garner et al. 2022), is heavily associated with eye imagery (see Stæhr 2014). Within conspiracy models, the placement of secret imagery is seen to be indicative of a secret code or clues as to the cabal’s existence (cf. Dyrendal 2012). Again, these allusions to conspiracy and antisemitic tropes indicate a similarity with other manifestations of fascist ideology, both past and present.

Example 11. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 12. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 13. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 14. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 15. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Of course, many of the examples cross the line from the laughable to the utterly ridiculous. However, some of the features of transvestigation discourses are not without their direct counterparts in offline politicking against transgender people in the UK and the USA. Politicians readily rely on the same tropes to legitimize their ideological positions and justify politico-legislative changes. Whether a pre-occupation with physiology in the form of genital configurations (Brooks 2023; Lavietes 2023) and other unsubstantiated references to biology (Meighan 2023), or false appeals to science to support conspiracy theories of social contagion in relation to both identity (Dodds 2023) and behaviour (Kessler 2023), there is evidently some mutuality between transvestigations discourses and politicised transphobia offline. Indeed, the more (seemingly) ridiculous aspects of platformed transvestigation discourse aside, it is exactly this mutuality between online and offline transphobia that arguably make the indeterminacy of transvestigations’ authenticity somewhat irrelevant. That is, many elements of such discourses and ideologies are granted legitimacy by dint of their reification in real-world practices that have significant and concrete impacts on – both transgender and cisgender – people’s capacity to safely and freely go on in the world.

4. Reclaiming hate, challenging received wisdom, and the art of trolling(?)

Other users’ responses to transvestigation posts also highlight key features that impact the indeterminacy of the wider transvestigation discourse’s authenticity. I categorise these responses into three main themes. The first is what I call ‘reclaiming hate’, wherein users respond to transvestigations – either directly to specific posts or more generally to the wider discourse – with humour and satire in order to mock the ridiculousness and question their authenticity. The second category I dub ‘challenging received wisdom’, which represents users who position themselves as sympathetic to the transvestigator’s cause, or at least broadly to gender-critical transphobia, but challenge their conclusions and methods. Finally, and perhaps the most indicative of transvestigations’ indeterminable authenticity is the category that I have deliberately named with/as a question: “the art of trolling?”. In this discursive manifestation, transvestigations are directed at known transphobes and gender-critical figures. As opposed to the ‘reclaiming hate’ category, a satirical intention in these posts is not evident and they are instead indistinguishable from other transvestigations.

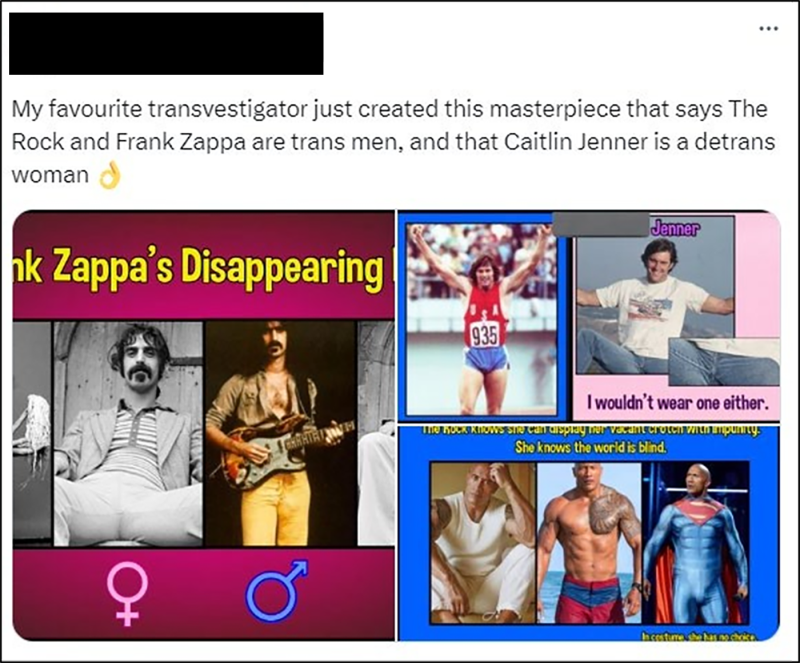

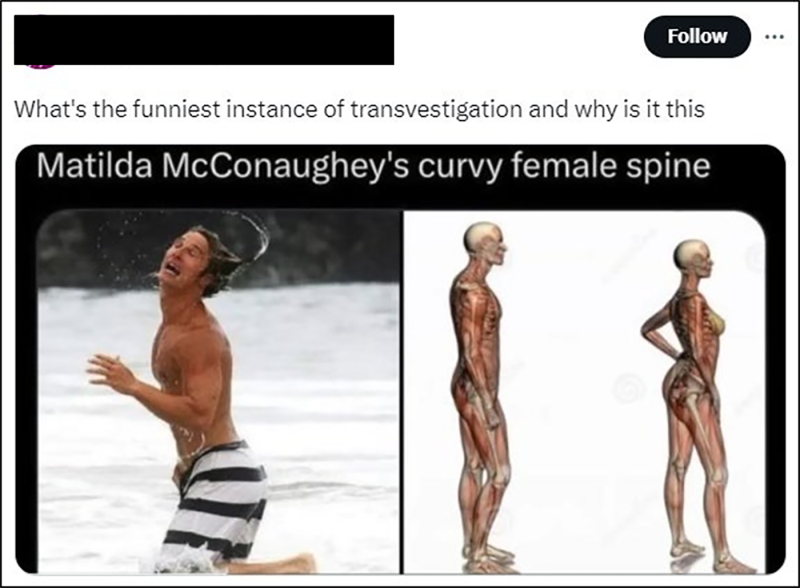

By re-contextualising transvestigation discourses as an object of humour, users deride their conspiratorial underpinning and attempt to negate their harmful intentions. In doing so, users share favourites (examples 16-17), post satirical re-appropriations (example 18), and directly challenge their authenticity (examples 19-20). Whilst users often take care to ensure that these responses are explicitly satirical and that they do not enable transvestigator’s to accumulate attention from such satire (e.g., by posting screenshots, rather than sharing content via a platform’s internal sharing mechanism), this re-appropriation of discursive strategies of one’s ‘ideological opponent’ is a direct example of the propensity for social media users to engage in mimetic antagonism. This phenomenon refers to the ‘type of [discursive] mirroring where combatants increasingly come to resemble each other’ (Jane 2017: 467).

Albeit an intentional mirroring, in the attention economy of social media, this kind of provocative satirisation potentially represents a direct attack on transvestigation discourses and its – assumedly – gender-critical and transphobic ideological bases. Indeed, this again calls into question the redundancy of determining the authenticity of transvestigation discourses. For those users without the capacity or inclination to critically interrogate the media they consume, these practices of satirisation may also serve to reinforce ongoing antagonism and vitriol in more general gender-critical fora.

Example 16. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 17. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 18. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 19. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 20. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

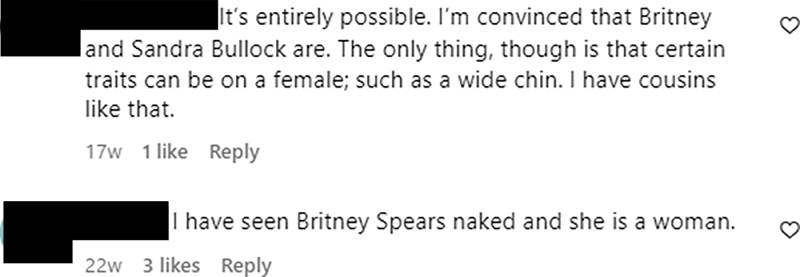

The argument that transvestigations could well be indistinguishable from other forms of authentic platformed transphobia, even by gender-critical individuals themselves, is reinforced in the way such users challenge the received wisdom of transvestigation posts. Such examples do not explicitly challenge the ridiculousness of transvestigations, more generally, but seek primarily to challenge the methods applied and conclusions drawn (examples 21-22). These challenges can also rely on personal experiences and anecdotes to refute claims made about specific celebrities (examples 23-24). Whilst these challenges evidently call into question the constitutive elements of transvestigation posts, they do not explicitly challenge the authenticity or appropriateness of transvestigations as a general socio-discursive practice.

Indeed, this lack of direct challenge to transvestigations, more broadly, lend legitimacy to the argument that they are indistinguishable from other socio-discursive manifestations of transphobia. The possibility of all such challenges also being posted by users pretending to be gender-critical notwithstanding, this has striking implications for the online-offline mutuality of transphobic discourses. That is, if ordinary citizens and organisations are already influenced by transvestigation-esque discourses in the justification for policing gendered spaces (e.g. Billson 2022; O’Sullivan 2021), then there is little in the way of preventing transvestigations from being directly referenced or otherwise re-appropriated in offline political discourse in the same way as other features of transphobia have already. After all, I have explained above how such offline political discourses already show substantive identity with tropes of more general transphobic discourse, which are also evident in transvestigations.

Example 21. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 22. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 23. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 24. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

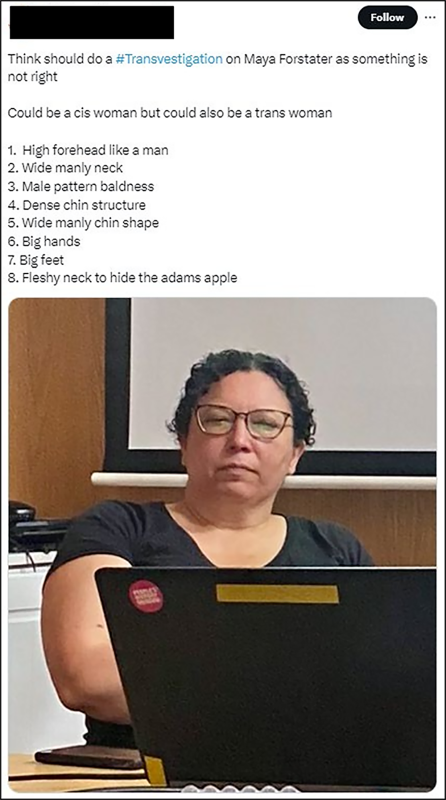

Another potential example of transphobia ‘eating itself’ is found in the final category of transvestigation responses, wherein there are specific examinations of and calls to transvestigate known gender-critical figures. Whilst such calls have been used by transgender users and their allies in the past during explicit attempts to troll transphobic users, there are also examples that are not explicitly satirical (examples 25-26). Given that there is no explicit indication of satire, and that such posts also include many of the transvestigation- specific discursive codes identified earlier in this paper, these examples represent the most direct challenge to the determinability of transvestigations’ inauthenticity. Perhaps these are examples of anti-transphobic trolling, which seek to highlight exactly the ridiculousness of transvestigations and their conspiratorial underpinning. Otherwise, they may represent a significant extension of the conspiracies of transgender ubiquity and the existence of an elite transgender cabal. That is, if taken as an authentic theory, the conspiracy potentially extends to the premise that an elite transgender cabal is so deeply engrained in society’s structures that elite transgender individuals are also embedded at the upper echelons of their own ideological opposition (i.e. within the ranks of transphobic and/or otherwise ‘gender-critical’ ideologues). Regardless of whether this is particularly sophisticated and ‘layered’ trolling or an over-extension of a transphobic and antisemitic conspiracy theory, these examples offer the most direct explanation for why we must reassess our critical engagement with social media as a vehicle for resisting, reproducing, and hegemonizing hate.

Example 25. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Example 26. Retrieved from X/Twitter.

Each of these categories of response arguably contributes to and represents examples of a social mediascape wherein authenticity – whether of hate, satire, or some other discursive function – is largely indeterminable. Indeed, the antagonistic communicative norms of social media’s attention economy – wherein ideological polarization is seemingly predicated on an ever-increasing radicalization of narrative – mean that even users engaged in the antagonism over transgender recognition (and on both sides) are evidently unsure of the (in)authenticity of transvestigations as a form of platformed transphobia. Again, this renders the authenticity – or not – of such discourses a moot point insofar as, regardless of their authenticity, transvestigations serve to reinforce antagonistic communication between ideological opponents in the social mediascape. Moreover, their indistinguishability from otherwise authentic gender-critical narratives means that transvestigations also represent a significant potential threat similar to that of more mundane manifestations of transphobia, which have already gained a foothold in offline political discourse. This is especially true in an offline politico-legal context that is, itself, increasingly indistinguishable from the attention-industrial complex of mass (social) mediatization.

Conclusion: Indeterminable authenticity in the attention economy

This paper sought not only to explain the indeterminable authenticity of transvestigation discourses and their conspiratorial underpinning, but also to highlight the implications such indeterminable authenticity has on our critical engagement with social media as a vehicle for reproducing, reinforcing, and resisting socio-structural inequalities. In so doing, I constructed two primary arguments: (1) transvestigations are partially reified in ongoing offline politico-legal manifestations of transphobia and risk being increasingly reified in the future; and (2) the techno-social affordances of social media render the authenticity of transvestigations as transphobic discourse a largely meaningless concept.

The indeterminable authenticity of transvestigations and the existing mutuality between online and offline transphobia arguably serves to shift the Overton window of what is palatable in Western political discourse. Transphobia evidently already has a foothold in ongoing politico-legal movements in the UK and the USA. Some features of transvestigation discourses, including the pre-occupation with genitals and fallacious appeals to scientific expertise, are already manifested in offline politics and (calls for) legislative change. That transvestigations are largely indistinguishable from other forms of – what we might call – authentic transphobia means that it is not unrealistic to presuppose that the further embedding of the foundational principles of transvestigation discourses is also a potential threat to social harmony and the (continuing) equitable socio-legal recognition of transgender identities and individuals. Indeed, similar narratives are already used to justify citizen policing of gender-segregated spaces, which has impacted both transgender and cisgender people. It is important to note that I am not, myself, engaging here in conspiratorial thinking. I do not think that politicians will introduce bone-measuring practices in order to enable access to sexed spaces. Rather, given the apparent similarities between transphobia and other (neo-)fascist discourses past and present, I am suggesting that such practices may also begin to bear similarity to such discourses. That is, people – cisgender and transgender alike – may (feel the) need to carry identity documents to prove their gender or sex at specific points in their daily lives.

Perhaps more critical to this forum as an exercise in academic dialogue, the indeterminable authenticity of transvestigations provokes significant questions about our engagement as critical discourse/media analysts with social media communication as an object of enquiry. My analysis here is intended to highlight that it is not (necessarily) enough to see social media as a direct reflection of society or as a causal mechanism of social inequality. Instead, I argue that the indeterminable authenticity of transvestigations points to the mutually constitutive relationship between social media discourse and society at large (both online and offline) is not simply bi-directional, but far more deeply enmeshed, entangled, and confused. What we might have previously identified as one discursive phenomenon or another – for example, satire or conspiracy – or even as one masquerading as another is not sufficient to account for the hypercomplexity of social media discourse.

Instead, transvestigations are an example of how discourses can be representative of both one thing and another simultaneously, albeit variably interpreted and interpretable. I therefore contend that hypercomplexity and indeterminacy is a largely unchangeable structural-discursive condition of our contemporary social mediascape. I end this paper, then, with a provocation: without radically rethinking our approach to critically analysing social media discourse, we are at risk of misunderstanding its ongoing, ever-evolving interaction with and impact on wider society, rendering our (inter)disciplinary pursuits towards social change redundant.