1. Context

Many scenes in our daily life are related to a certain domain, and, consequently, some type of specialised discourse: e.g., when practicing our profession or when reading a text related to a certain domain, like a weather report (meteorology) or a horoscope (astrology).1 As such, a cognitive linguistic framework which aims to be a valid theory about language should take into consideration the specialised contexts in which language is used and, therefore, also the possible specialised features of language. Within the framework of Construction Grammar (CxG), this raised the question of whether constructions can have specialised manifestations – and, if so, whether it is even possible to talk about specialised constructions (Fischer and Nikiforidou, 2015; Bücker et al., 2015; Gautier and Bach, 2019).

A first case-study on the matter is provided by Gautier and Bach (2019). After having examined be- and have-structures in French oral wine descriptions as in (1), they argued that these can only be explained when integrating other knowledge components, which appear to be “encapsulated” in the constructions themselves. Their analysis of a corpus of professional wine descriptions in French has shown that both verbs are only used in pre-formed structures with specific slots directly associated with (i) the specialised knowledge about wine production and (ii) the discursive and epistemic knowledge about the structuration of wine descriptions as a discourse pattern:

| (1) | a. Fr.: […] sinon on a les Gevrey Chambertin les Sevrey de chez Olivier Juin en 2013 […] |

| “otherwise we have the Gevrey Chambertin les Sevrey from Olivier Juin from 2013” | |

| b. Fr.: […] donc là on est vraiment sur le fruit croquant […] | |

| “and so this one is more crispy and fruity” |

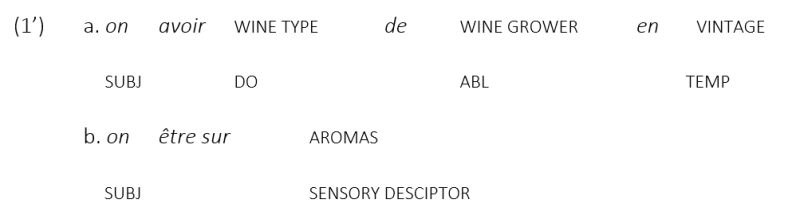

The constructions postulated here can be schematised as follows:

In both cases, these constructions, which can only be found in these discourse patterns, do not correspond to any known valency schemata of the verbs être (‘to be’) and avoir (‘to have’). In (1a/1a’), the construction is linked with definitory segments of wine production in France: wine has a precise origin that gives it its name, is grown by an identified producer and is characterised through the vintage. In (1b/1b’), the construction refers to the structure of wine description that always includes a presentation of the aromas. In both cases, the subject position is consistently occupied by on.

An overview of the current CxG-literature shows that only a few constructions in a select array of specialised discourse traditions have been considered so far. So, first, the hypothesis that constructions do have specialised manifestations needs to be sustained by more data, involving different constructions, domains and languages. Secondly, on a more theoretical level, many questions remain unanswered, like (i) how these specialised manifestations can be linked to the cognitive architecture of the domain, and (ii) whether we can – based on (a) the domain-related features the constructions gain and (b) their position within the constructicon – even call them specialised constructions, rather than specialised manifestations of general constructions. To this aim, this paper considers so-called existential constructions (e.g., constructions with er is/zijn; het is; het wordt in Dutch – see Bentley et al., 2013) in a corpus of Flemish weather reports to find out whether they show domain-related features (Section 4.2) and to elaborate on the questions raised above (Section 5).

2. Corpus

This exploratory study utilises a pilot corpus of Flemish newspaper-weather reports. These weather reports are often cited as classic examples of text genres in various textbooks (Liégeois, 2021: 199; 2022) since they show (i) a highly routinised linguistic structure reflecting (ii) a conventionalised cognitive architecture of the specialised field. This makes newspaper-weather reports an excellent experimental ground for the hypothesis explained above.

We created a corpus of such reports using two Flemish newspapers, De Standaard and Het Laatste Nieuws, over the span of one year, from July 2019 until August 2020. The corpus encompasses 124,000 tokens, taken from 334 weather reports.

A first manual analysis of a sample of texts of each newspaper, based on the four criteria singled out by Gautier (2009) – main text function (a), propositional contents (b), information structure (c) and stylistic and formulative prototypical features (d) – confirms their highly routinised linguistic structure:

- The informative text function dominates these texts, leaving no place for other ones – reflecting the expectations of the readers who consult such reports to gain basic information to guide their own behaviour (e.g., “Can I go for a walk without an umbrella?”).

- The main argument (or topic) of the texts is nearly always the evolving weather situation, expressed through various categories and based on an opposition between the current weather situation (meteorological observations) and expectations for the future.

- The information structure of the text is marked by the many temporal and locative segments which situate the weather in time and space and therefore function as thematic indicators. Each paragraph explains the weather situation on a certain day (e.g., maandag, ‘Monday’) or moment of the day (e.g., vanavond, ‘tonight’). This temporary weather situation, in turn, is highlighted for different places (e.g., aan zee, ‘at the coast’; in de Ardennen, ‘in the Ardennes’).

- Regarding the stylistic and formulative prototypical features, the dominance of the topic (weather) and informative text function identified above together with the dependence on temporal and locative categories amount to a highly structured text with discourse patterns consisting of weather-related, temporal and locative segments. Exceptionally frequent is the following pattern, in which a temporal or locative segment serves as the primary indicator, the weather as the topic and a temporal or locative segment as the secondary indicator:

[Time/Place]indicator [Weather]topic [Time/Place]indicator

This initial description of our corpus aligns closely with Meulleman and Paykin’s (2023) analysis of French weather reports, as well as with the analyses by Liégeois (2021, 2022) on German and Italian weather reports, and Liégeois et al. (2023) on Norwegian, Swedish, and Dutch weather reports. Regarding the possible existence of specialised constructions, we hypothesise that the pattern singled out above converges with other constructions frequently used in the specialised text genre (i.e., weather reports). We further postulate that the constructions with which this pattern converges have some features (regarding meaning/form or function) which make them particularly suitable for the purpose of these specialised texts (i.e., informing people about the weather). This convergence, in turn, would lead to specific formal features, valency schemata and could even generate new meanings.

3. Pilot study

3.1. Object of study

In this paper, we will consider existential constructions (see McNally, 2011; Bentley et al., 2013) within the domain of weather reports. Considering that previous literature has often pointed out the nominal style of this text genre (Liégeois, 2021: 215‑216) – meaning that the most substantial information is carried by nouns or adjectives and that the verbal field is mostly occupied by modal verbs or copulas –, these constructions can be expected to appear frequently in weather reports. They are best exemplified by the following English sentence (2):

| (2) | Eng.: There are some books on the table. (Bentley et al., 2013: 1) |

In Dutch, het is (‘it is’), er is/zijn (‘there is/are’) and het wordt (‘there will be’) appear in such existential constructions. Bentley et al. (2013: 1) explain their structure with the following schema (3):

| (3) | (expletive) [proform] [copula] [pivot] [coda] |

A proform (There) serving as the subject of the phrase is combined with a copula (are), a pivot, which is mostly found in post-copular position (some books), and a coda (on the table), i.e., an addition like a locative or temporal phrase.

Their valency schema does not adhere to the canonical valency schemata of copular verbs (see (3); Beaver et al., 2005). Accordingly, Bentley et al. (2013) state that “Existential constructions are constructions with non-canonical morphosyntax which express a proposition about the existence or the presence of someone or something in a context” (Bentley et al., 2013: 1; our emphasis).

Within the above definition, we highlighted two elements that appear promising for this pilot study: (a) the “non-canonical morphosyntax” and (b) the “importance of the context”:

- CxG approaches of predicate-argument structures enable us to treat the question of the non-canonical morphosyntax by considering the whole structure as a form-meaning pairing, without solely looking at syntactic features and, above all, without postulating that structures which are used differently, as in so called “normal” conditions, are always deviations from the norm and “non-canonical”.

- If the context is such an important factor, then it should be defined precisely, as well as investigated with regard to how it is implemented in the construction – especially in the case of specialised language use.

In weather reports, these existential constructions have already been studied by Liégeois et al. (2023) for Norwegian, Swedish, and Flemish.2 Their research, in fact, suggests that existential constructions in weather reports exhibit various domain-related constructional features (see Section 5). Our analysis adopts the same methodology but utilises a different corpus of Flemish weather reports, although there is some overlap in the texts. Thus, the goal and relevance of our study is twofold: on the one hand, to verify or falsify their findings; on the other, to integrate these domain-related features into CxG theory, with particular emphasis on the constructicon and the interaction between CxG and frame semantics (see Section 5).

3.2. Procedure

After compilation, the corpus was processed using Sketch Engine. We first sought to describe the lexical features of the texts by looking at the keywords list – which singles out text-specific vocabulary through a statistic comparison with the Dutch Reference Corpus3 (hence “DRC”) – and the frequency list of verbs. Based on this, we were able to verify whether the semantic categories of weather, time and place (the discourse pattern) dominate our entire corpus and deliver some first insights into the used verbal categories. Thereafter, we looked at the (possibly domain-related) constructional aspects of existential constructions with er is/zijn, het is and het wordt. More specifically, we considered (i) their frequency, (ii) possible form-specific features, (iii) valency schema, and (iv) meaning.

4. Results

4.1. Lexicological analysis

4.1.1. List of specific terms

Considering this corpus as a specialised one, a first traditional approach to characterise it is to look at terminology. The corpus’s single-word keywords list (consisting of 100 items) shows that very few verbs – even specialised ones – can be considered as frequently present and corpus-specific. The only verbs included in the list of specific terms are waaien (‘blow’) and schommelen (‘fluctuate’). Instead, the list contains mostly nouns designating weather phenomena – e.g., opklaring (‘clearance’), rukwind (‘gust’) –, indicating that nominal structures dominate the texts. Other than weather-related nouns, we find two types of circumstances: place – e.g., Samber (‘Sambre [Belg. River]’), zuidwest (‘southwest’) – and time (e.g., maandag ‘Monday’, ‘s ochtends ‘in the morning’). This reflects the discourse pattern singled out in Section 2 with weather as the topic and time/place as situational indicators.

These preliminary quantitative findings suggest that domain-related nominal terms are used within structures presenting domain-transcending verbs – among them existential structures. This can be confirmed by taking a closer look at the frequency of verbs in Section 4.1.2.

4.1.2. Frequency list of verbs

Within the frequency list of verbs – produced with the POS-tagged module of Sketch Engine that also provides a normalised frequency p/million –, almost no specialised verbs are featured. Waaien en schommelen only occupy the 6th and 7th place and more general verbs like zijn (‘be’) and worden (‘become’) are used instead. This confirms our first observations about verbs being domain-transcending (see Section 4.1.1.) and corresponds to previous observations regarding the nominal style from weather reports (Liégeois, 2021: 215‑216).

Table 1: 10 most frequent verbs

| Item | Freq. | Normalised Freq. | DRC |

| zijn | 1,821 | 14,480.97 | 18,279.13 |

| worden | 1,538 | 12,373.19 | 7,282.75 |

| blijven | 899 | 7,232.44 | 741.05 |

| kunnen | 712 | 5,728.03 | 5,918.90 |

| liggen | 584 | 4,698.27 | 635.23 |

| waaien | 393 | 3,161.68 | 10.74 |

| schommelen | 375 | 3,016.87 | 0.26 |

| vallen | 353 | 2,839.88 | 329.12 |

| nemen | 255 | 2,051.47 | 869.25 |

| verwachten | 247 | 1,987.11 | 170.83 |

The verb zijn shows the highest frequency, followed by worden. Both have a normalised frequency of over 10,000, with worden even showing an overrepresentation of 5,000 words p/million when compared with the DRC.

The following Section 4.2 will discuss some of the structures with zijn and worden, which we will argue to be (specialised) existential constructions.

4.2. Constructional analysis

4.2.1. Frequency

The verbs zijn and worden are, in fact, mostly used in existential structures similar to the ones discussed in Section 3.1. The verb zijn is accounted for 62.05% (1,130/1,821) of the time with the pro-forms er4 (404 attestations) or het (726 attestations) in subject position. Structures with the verb worden appear 64.69% (995/1,538) of the time with the pro-form het in subject position (4):

| (4) | a. Dt.: Morgen is er eerst vooral richting Franse grens veel bewolking met nog wat regen […] |

|

“Tomorrow there is initially a lot of cloud-cover with some rain towards France” |

|

| b. Dt.: In het noorden en het oosten is het droog met brede opklaringen. | |

| “In the North and the East it is dry with extensive sunny spells” | |

| c. Dt.: Het wordt vandaag wisselend bewolkt met in de loop van de dag enkele buien […] | |

| “It will be partly cloudy today with some rain showers later on” |

This leads to a relative frequency of 3,258.06 for er is/zijn, 5,854.84 for het is and 8,0224.193 for het wordt. These frequencies are remarkably higher than those of er is/zijn- (1,206.86) and het is-structures (2,794.13) in the DRC. Het wordt-structures also appear more frequently than in the DRC (7,868.10), but here the difference is less notable.

4.2.2. Word order

Our corpus-based analysis directly points to form-specific features of the three structures above. Rather than following the canonical Dutch word order SV(O), 76.90% (869/1,130) of the structures with zijn and 73.77% (734/995) of the ones with worden demonstrate subject inversion (5), leading up to a total of 1,603 structures with subject inversion:

| (5) | a. Dt.: Maandag zijn er afwisselend zonnige en bewolkte periodes. |

| “Monday there are variable sunny and cloudy spells” | |

| b. Dt.: In het noordwesten is het vrijdag zwaarbewolkt maar droog. | |

| “In the Northwest it is overcast but dry on Friday” | |

| c. Dt.: In de loop van de namiddag wordt het zo goed als droog vanaf het noorden. | |

| “In the course of the afternoon it will be as good as dry from the north” |

This subject inversion is, however, also the main word order with the relevant structures in the DRC. Er is/zijn appears with subject inversion 58,26% of the time, het is 55,56% and het wordt 74,30%. Subject inversion with zijn appears more frequently in our own corpus, whereas subject inversion with het wordt is slightly – less than one percentage point – more present in the DRC.

The following subsections will focus on subject inversion-constructions like the ones in (5).

4.2.3. Collocations and valency

The subject inversion of the three constructions is always imparted upon them by the left context (LC). This LC is almost exclusively occupied by temporal ((5a) T-SEG) and locative segments (5b,5c) L-SEG), which situate the weather in time or space. These components, in turn, force subject inversion upon the existential constructions (see Table 2).

Table 2: Distribution of components in the LC

| is/zijn er | is het | wordt het | Total | |

| T-SEG | 202 | 422 | 617 | 1,241 |

| L-SEG | 111 | 90 | 78 | 279 |

| T/L-SEG | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| Other | 13 | 30 | 31 | 74 |

The above table (Table 2) demonstrates the high frequency of these T-SEG and L-SEG in the LC, with T-SEG being attested for 1,241 times, L-SEG 279 times and temporal/locative ones (T/L-SEG) 9 times, whereas other components only account for a total of 74 attestations.

Not only in the LC, but also in the right context (RC), routinised patterns of components may be found. In this case, only three segment types appear after the verbal phrase (see Table 3):

Table 3: Distribution of components in the RC

| is/zijn er | is het | wordt het | Total | |

| T-SEG | 98 | 222 | 170 | 490 |

| L-SEG | 64 | 70 | 194 | 328 |

| W-SEG | 322 | 543 | 738 | 1,603 |

Always present is the weather-related component (W-SEG), which is accounted for 1,603 times. Other possible components in the RC specify time (T-SEG) or place (L-SEG).

The above observations (see Table 2 and 3) about the LC and RC correspond to the discourse pattern singled out in (2), in which the weather functions as the main topic of the text, and temporal and locative segments as primary (in the LC) and secondary thematical indicators (in the RC). This pattern is also exemplified in the sentences in (5b) and (5c) above. Concerning the structure laid out by Bentley et al. (2013: 1) (see Section 3.1), we should point out that our existential constructions can, in fact, have two codas (time and place). We therefore argue that these are specialised valency schemata of the construction. However, Liégeois et al. (2023: 173) note that T-SEG and L-SEG frequently occur with general is/zijn er-, is het-, and wordt het- structures in the DRC (see Section 5). Yet, other lexical segments – i.e., those unrelated to the categories of time, weather, or place – dominate these lists. In contrast, weather appears to function as a slot specific to existential constructions in weather reports. Thus, the high frequency and near-exclusive occurrence of these segments in the relevant structures, combined with the presence of two codas, constitutes their specialised manifestations.

4.2.4. Meaning

The last part of our constructional analysis questions whether the discourse pattern imposes a new meaning on the verbal phrase. This is indeed the case for those constructions with is/zijn er and is het that appear with a temporal segment as primary/secondary frame-setting topic (see the examples in Section 5). These verb phrases typically denote a present event, yet here the discourse pattern (i.e., the temporal segment denoting a future event) imposes an inchoative-future-existential reading on them.

This can be considered the most striking feature of existential constructions in our corpus of weather reports, as we would not expect constructions with worden and zijn, whether existential or not, to exhibit the same aspectual properties. In the following, we will argue that this inchoative-future-existential reading is a specialised characteristic of the existential constructions found in (Flemish) weather reports (see Section 5).

5. From specialised frames to specialised constructions: The pressure of the domain

Drawing from the discussion in Section 4.2, we can enlist the following specialised constructional features for the existential constructions under consideration: (i) their high frequency (see Goldberg, 2006: 5) and (ii) form-specific features (subject inversion, which, however, is already very frequent with zijn and worden-structures in the reference corpus), (iii) their specific valency schemata (with respect to Bentley et al.’s 2013 representation), and (iv) the inchoative-future reading laid upon the is het- and zijn/is er-structures. This list corresponds to the specialised constructional features singled out by Liégeois et al. (2023: 174), meaning that we can confirm the results from this study.

We now turn to the theoretical questions posed in Section 1: (i) how such specialised manifestations can be linked back to the cognitive architecture of the domain, and (ii) whether we can call them specialised constructions instead of merely specialised manifestations of constructions.

When it comes to the first question, frame semantics – as a model aiming at representing knowledge structures evoked by words – may be viewed as a starting point for the description of the cognitive architecture of the underlying domain (Dalmas and Gautier, 2018). The relation between this cognitive framework and that of CxG has been emphasised from the beginning of CxG:

It has been argued that meanings are typically defined relative to some particular background frame or scene, which itself may be highly structured. I use these terms […] to designate an idealisation of ‘a coherent individuatable perception, memory, experience, action, or object’. (Goldberg, 1995: 25; our emphasis.)

For English, FrameNet defines a weather-frame as “ambient conditions of temperature, precipitation, windiness, and sunniness pertain at a certain Place and Time.”

This definition highlights the three components identified through both the 4-level analysis of the corpus in Section 2 and the postulated weather-specific existential constructions described in Section 4.2: weather phenomena (see the definition above), time (a) and place (b):

| Time [T]: | This FE identifies the Time when the weather occurs. |

| Place [P]: | This FE identifies the Place where the weather occurs. |

The categories of time and place become even more relevant in weather reports, since they are needed to aptly describe the weather to the lay audience (Liégeois, 2021: 207). If we take the frame-semantic representation as being representative of the domain’s cognitive (ontological) architecture, we see a full convergence between this cognitive architecture and the existential construction as described by Bentley et al. (2013). This mirrors what we tried to capture in the 4-level model discussed in Section 2. Level 1 – the main text function – is not isolated, as it can be looked at as a kind of meta-frame of pragmatic nature organising the whole discourse pattern (Czulo et al., 2020). For future research on constructions in specialised discourse, we argue that FrameNet can serve as a valid point of reference regarding the domain’s cognitive architecture (see our conclusion).

Concerning the second question, we can say that for realising these (specialised) constructions one needs to know the construction (existential construction) and the discourse pattern(s). This implies two things:

- First, based on the discourse patterns and needs of the domain, constructions are chosen which aptly suit those patterns/needs. This regards the nominal style (e.g., the use of verbs like zijn and worden), but also the need for inversive structures, due to locative and temporal segments appearing at the beginning of the clause. This makes existential structures, which already frequently appear with subject inversion in general (see Section 4.2.2) as well as T- and L-SEG (see Section 4.2.3), apt candidates that fit within the style/patterns of weather reports. The combination of the patterns with the constructions, in turn, leads to specialised features, like existential constructions with two codas and zijn/is er- and is het-constructions with inchoative-future-existential meaning. The aspect (inchoative-future-existential) is thus automatically laid upon the constructions by the domain, regardless of the “general” aspect of the verb.

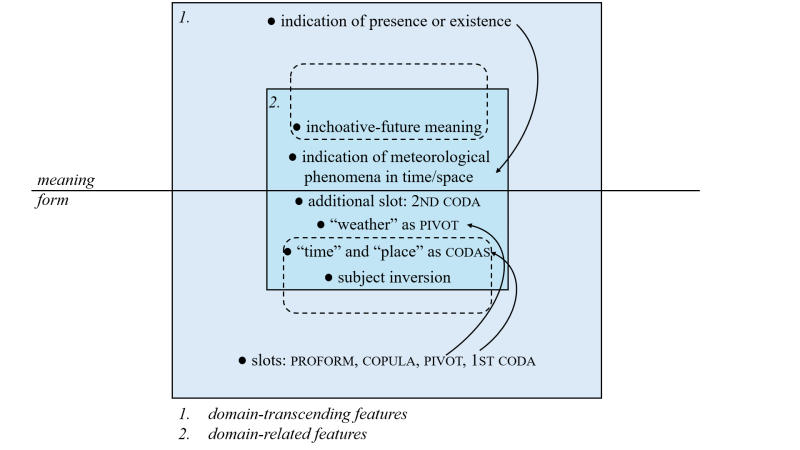

In this regard, a formalisation of our specialised manifestations, inspired by Croft and Cruse (2004) but adapted to distinguish between general language and specialised communication, should take the following form (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Formalisation of existential constructions in Flemish weather reports

The features in 2. are specific to the realisation of existential constructions in weather reports. However, as Figure 1 illustrates, different specialised features – such as the indication of meteorological phenomena in time/space, “weather” as the pivot, and “time” and “place” as codas – represent specific semantic or lexical instances of the general constructional features. Similarly, the dashed circled features already appear frequently in general existential constructions (e.g., “time” and “place” as codas, subject inversion) or are automatically evoked by specific existential constructions – such as wordt het-structures, which automatically carry a future meaning. Regardless, these features are always automatically imposed on the constructions by the domain (see above).

- Secondly, since speakers already need to know the construction, these specialised manifestations should, within the constructicon, be located below the construction-level. A question which remains, however, is whether the point of convergence between the construction and the knowledge of the domain should be situated above or on the level of constructs. The fact that new meanings and formal features might be realised through this convergence, is an element in favour of the former, in which case we might, in fact, speak of specialised constructions, situated on some kind of secondary construction-level. However, considering – as mentioned in our introduction – that there are many domains and specialised discourse traditions, which all have specific discourse patterns, this would lead to an explosion of constructions, which is an argument in favour of the convergence being oriented at the level of constructs. Should they be situated at the construct-level, a further question will need to be addressed: namely how the abstract discourse patterns singled out is Section 2 fit within CxG-theory or even the constructicon, since they impose the new features on the constructions.

Conclusion

Our paper dealt with the relationship between constructions (in the sense of CxG) and specialised discourse. Looking at existential constructions (Dt. er is/zijn; het is; het wordt) in Flemish weather reports as a case-study, we considered their possible specialised features, and tried to shed light on the question (i) how these specialised manifestations can be linked back to the domain, and (ii), whether they might even be called specialised constructions, for which (a) their domain-related features and (b) position in the constructicon were taken into consideration.

In our discussion of the results, we were able to link the frequency (Section 4.2.1), form-specific features (Section 4.2.2), valency schemata (Section 4.2.3) and meaning (Section 4.2.4) of these constructions back to the discourse pattern singled out in Section 2, which regarded the semantic categories of weather, time and space. Looking at the frame-semantic representation of “weather”, we argued that these specific manifestations coincided entirely with the domain’s cognitive architecture. We, in turn, situated these specialised manifestations below the level of constructions. However, this led to the question of whether there exists an intermediary level between constructions and constructs where the constructions and patterns converge, or whether this convergence should simply be situated at the level of constructs. We encourage future research to consider this theoretical question in more depth.

The hypothesis of specialised constructions proves to be an interesting one. However, as previously stated in Section 1, it remains imperative that more empirical research is done. Our theoretical discussion in Section 5 is intended as a starting point for those studies, which should not only concern the constructions and specialised discourse patterns discussed here, but many other constructions and specialised knowledge domains (e.g., legal, medical and economic texts) and in different languages as well. A final suggestion for future studies is to consider the interface between constructions and frames, particularly the relationship between CxG and frame semantics (see Section 5). As Bach (2021) has pointed out, many constructions are associated with or even evoked by specific frames. Given that many frames, like the weather-frame, are linked to a particular domain, exploring this interface could provide a valuable starting point for addressing the questions raised at the end of our analysis.