We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers who brought interesting questions, suggestions and helped us improve the final version of this paper. We also thank the participants and the organisers of the “Adverbs and Adverbials: Issues in semantic and functional ambiguity” conference, which took place at the Nicosia University, in Cyprus, in a hybrid format on 18-19 May 2023. We also thank the audience of the “Simpósio Temático ST 39 – Estudos Formais de Sintaxe” at the XIII International Congress of the Brazilian Linguistic Association (Abralin) for their questions and comments, and the members of our research group, LaCaSa – Cartographic Syntax (from the University of Campinas, UNICAMP), where two versions of this paper were presented. We also thank Flore Kedochim for proofreading the French “résumé”. Finally, both authors acknowledge the financial support provided by FAPESP – the São Paulo Research Foundation – through research grants awarded to them (#2023/16142-0 and #2023/17225-7).

Introduction

In this paper, we turn to Brazilian Portuguese (henceforth BP) and Chilean Spanish (henceforth CS) in the study of some aspectual adverbs from different classes which, according to Cinque (1999, 2004), have a dual source both concerning their position in the universal hierarchy of adverbs and functional categories (also called “functional spine”) and their scope. We will be descriptively calling these adverbs “duplicating adverbs” throughout this paper.

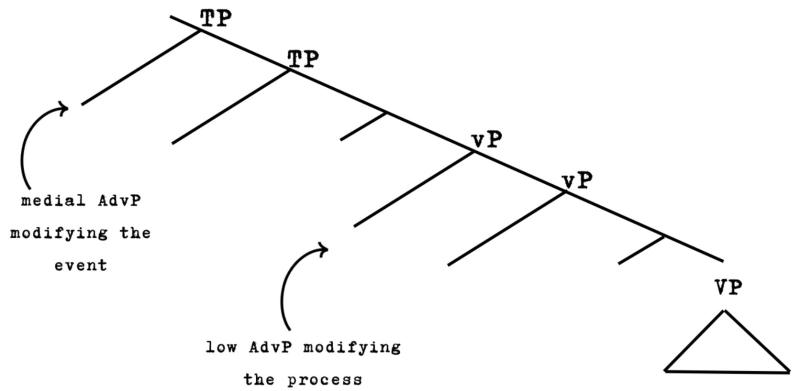

Duplicating adverbs can occupy two distinct positions within clausal structure. As noted by Cinque (1999, 2004), pre-minimalist studies had already observed their association with these positions, each linked to a different scope. A duplicating, “ambiguous” adverb quantifies either over the event – which corresponds, in terms of clausal composition in pre-minimalist work, to the IP domain – or over the process – which corresponds to the VP or thematic domain.1 These two different scopal configurations have been interpreted as the result of adjoining the (same) adverb to two distinct loci in the clausal spine. Thus, adjuncts modifying the event would be adjoined to TP (or to IP) while adjuncts modifying the process would be adjoined to vP/VP, as shown in Figure 1.2

Figure 1: The two scope positions in traditional adjunction approaches to adverbial modification

Languages may vary regarding the specialisation of adverbs for either scope zone. For instance, in the case of habitual adverbs, Italian distinguishes between the two scope positions for this category: di solito (‘usually’) occupies the higher position (labelled “Asp(I)” as detailed below), while abitualmente (‘usually’) is the sole candidate for the lower position (“Asp(II)”), as shown in (1). English, by contrast, does not exhibit such specialisation (see (2)). The examples in (1)‑(2) are taken from Cinque (1999: 204, n. 36).

| (1) | a. | Gianni (di solito) non prende più (*di solito) la metropolitana. | (Italian) |

| “G. (usually) no longer (usually) takes the subway.” | |||

| b. | G. (??abitualmente) non prende più (abitualmente) la metropolitana. | (Italian) |

| (2) | a. | ?They usually no longer win. |

| b. | They no longer usually drink much beer. |

In English, the same lexical item (usually) occupies both positions – one to the left and one to the right of no longer (see (2)). In contrast, Italian differentiates between the two: the PP di solito (‘usually’) exclusively fills the higher event-related position (see (1a)), while the AdvP abitualmente (‘habitually’) is specialised for the lower process-related one (see (1b)).

As already mentioned, in this paper we will turn to “duplicating” adverbs in BP and CS, limiting ourselves to those with specific aspectual import – see their description in Section 1. Following Cinque (1999, 2004), we will use the (I) index for the higher source, i.e., for adverbs modifying the event, and the (II) index for those modifying the process (and placed closer to the vP/VP projections) (see Section 1). As we will see throughout Section 2, an interesting cross-linguistic pattern is found in these two languages:

| (i) | Asp(I) adverbs can only appear to the left of the main V in BP and CS, with the exception of the AspSgCompletive adverb, due to the obligatory raising of the main V in both languages, to which we will return in Sections 2.1 and 2.2 (see (3)); |

| (ii) | Asp(II) adverbs can both be lexicalised by an adverb ending in -mente or, preferentially, by the corresponding PP form (P + NP) in BP; in CS, the lowest position can only be realised by the PP (see (4), (4’)). |

The sentences in (3), (4) and (4’) illustrate the pattern just mentioned in (i) and (ii).

| (3) | AspFrequentative(I): | ||||

| a. | João | frequentemente/*com frequência | sai | com as mesmas pessoas. | (BP) |

| J. | often/with frequency | goes-out | with the same people | ||

| b. | Juan | frecuentemente/*con frecuencia | sale | con las mismas personas. | (CS) |

| J. | often/with frequency | goes-out | with the same people | ||

| “J. often goes out with the same people.” | |||||

| (4) | AspFrequentative(II): | ||||

| a. | João | sai | frequentemente/com frequência | com as mesmas pessoas. | (BP) |

| J. | goes-out | often/with frequency | with the same people | ||

| b. | Juan | sale | ??frecuentemente/✔con frecuencia | con las mismas personas. | (CS) |

| J. | goes-out | often/with frequency | with the same people | ||

| “J. goes out with the same people often.” | |||||

| (4’) | AspFrequentative(II): | ||||

| a. | João | sai | com as mesmas pessoas | frequentemente/com frequência. | (BP) |

| J. | goes-out | with the same people | often/with frequency | ||

| b. | Juan | sale | con las mismas personas | *frecuentemente/con frecuencia. | (CS) |

| J. | goes-out | with the same people | often/with frequency | ||

| “J. goes out with the same people often.” | |||||

While only an adverb ending in -mente (e.g. frequentemente/frecuentemente ‘often’) can fill the higher, Asp(I) projections in both languages (see (3a,b)), there is variation regarding the candidate(s) which can fill the lowest, Asp(II) projections, namely, those positions from which the adverb has scope over the process. An adverbial PP (e.g., com frequência/con frecuencia ‘often’) is a good representative in both languages, while only BP also allows for an adverb ending in -mente (frequentemente) to fill that position (see the data in (4) and (4’)). As we will see from now on, this pattern is consistent with all classes of duplicating adverbs (see Section 1).

This being said, the main goal of this paper is to review some cases of apparent ambiguity3 as featured by “duplicating” adverbs from distinct aspectual classes (those detailed in the next section) in BP and CS. We aim to argue, on Syntactic Cartography grounds (see, a.o., Cinque, 1999, 2004; Rizzi, 1997, 2004; Cinque and Rizzi, 2010; Laenzlinger, 2011; Rizzi and Cinque, 2016), that this ambiguity is much more apparent than real. With this main goal in mind, we take/develop a set of syntactic tests which can help one: (i) determine the position of “ambiguous” adverbs – those indicated by the indexes I and II in Cinque’s (1999) hierarchy (completive, frequentative, repetitive, inceptive, celerative) –in sentence structure; and (ii) distinguish their different semantic contents.

To achieve these goals, the paper is organised as follows. First, we make a brief review of the theoretical framework, paying particular attention to the classes of duplicating aspectual adverbs studied here. Next, in the subsections of Section 2, we go through seven syntactic configurations – some of them illustrating particular syntactic phenomena (V raising, VP ellipsis, etc.) – which can be taken as diagnostic tools to discriminate between the two sources for duplicating aspectual adverbs. In Section 3 we interpret, from the syntactic perspective penned by Syntactic Cartography, the results of the preceding section. Finally, in the subsequent section we bring the main conclusions and wrap up the paper. There is also an “Appendix” featuring eight tables with the complete set of data used in this work for consultancy.

1. Theoretical background

Within the Cartographic framework, based on Cinque’s (1999) seminal work, adverbs are considered to be specifiers of rigidly ordered IP-internal functional projections, and not simple adjunctions. In Cinque’s representation of the IP domain, this field is formed by over 30 functional categories. Each category – which corresponds to an autonomous functional projection – making up this inflectional domain or IP has its specifier position potentially filled by an adverb matching the (same) semantic content of the corresponding head. By hypothesis, this configuration is part of the initial state of the Language Faculty – meaning that it should apply to all natural languages. Given that adverbs occupy rigidly fixed positions, they can be used as diagnostic tools to determine the raising of other constituents, such as the raising of the Verb and its arguments. This proposal is motivated by the fact that the co-occurrence of two adverbs in a given sentence is only possible if they do not belong to the same category/class and if they are linearised in one of the two possible relative orders, as shown in (5).

| (5) | a. | John doesn’t any longer always win his games. |

| b. | John doesn’t always any longer win his games. (Cinque, 1999: 33) |

Category is taken here in Jackendoff’s (1972) sense: two items belong to the same category if their co-occurrence is banned.4 They belong, on the other hand, to different categories if their co-occurrence is allowed. Once Cinque identified the categories displayed in (6) – essentially on the basis of previous work from Linguistic Typology and from (distinct) theories of Grammar, including but not limited to Generative Grammar –, he turned to precedence-and-transitivity tests5 in order to determine the relative order of such categories.

| (6) The Universal Hierarchy of Adverbs and Functional Projections (Cinque, 1999: 106) |

| [frankly MoodSpeechAct > [luckily MoodEvaluative > [allegedly MoodEvidential > [probably ModEpistemic > [once TPast > [then TFuture > [perhaps MoodIrrealis > [necessarily ModNecessity > [possibly Modpossibility > [usually AspHabitual > [finally AspDelayed > [tendentially AspPredispositional > [again AspRepetitive(I) > [often AspFrequentative(I) > [willingly ModVolition > [quickly AspCelerative(I) > [already TAnterior > [no longer AspTerminative > [still AspContinuative > [always AspContinuous > [just AspRetrospective > [soon AspProximative > [briefly AspDurative > [(?) AspGeneric/Progressive > [almost AspProspective > [suddenly AspInceptive > [obligatorily ModObligation > [in vain AspFrustrative > [(?) AspConative > [completely AspSgCompletive(I) > [tutto AspPlCompletive > [well Voice > [early AspCelerative(II) > [out of nowhere AspInceptive(II) > [again AspRepetitive(II) > [often. AspFrequentative(II) > [completely AspSgCompletive(II) V |

Our starting point is the acknowledgment of the validity of this hierarchy across languages. Work by Tosqui and Longo (2003), Sant’Ana (2005, 2007), and Tescari Neto (2013, 2019) have already tested the validity of the hierarchy in (6) for BP. Wechsler (2023) also tested its validity on CS. Hence, there is motivation for replacing the representation provided in Figure 1 with an alternative assuming a more fine-grained structure, like the one in (6). In this revised representation, each distinct semantic class of adverb – here identified as a separate category– would correspond to a distinct syntactic class of adverbs. This amounts to saying that adverbs modifying the event – those identified with the (I) index (i.e., the adverbs from distinct Asp(I) classes) – are not taken to simply adjoin to the TP, as in Figure 1. Rather, they come in distinct specifier positions which are rigidly ordered in terms of a hierarchy of categories. By their turn, adverbs modifying the process – namely, those identified with the (II) index (i.e., the adverbs from distinct Asp(II) classes) – are not taken to simply adjoin to the vP, as in Figure 1; they also come in distinct specifier positions.

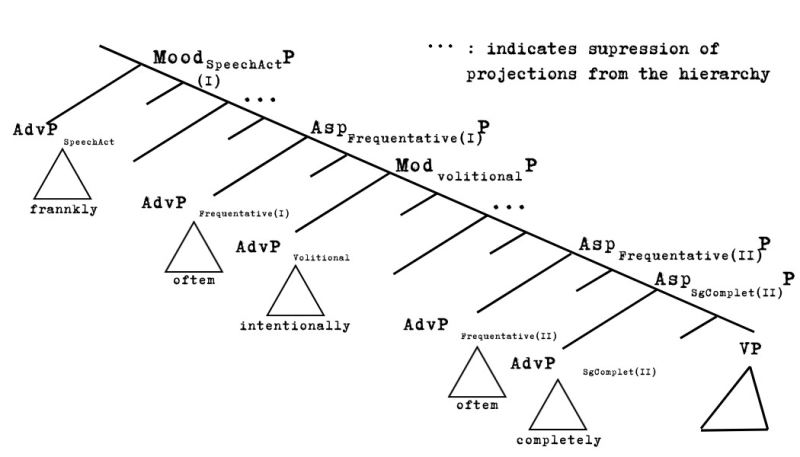

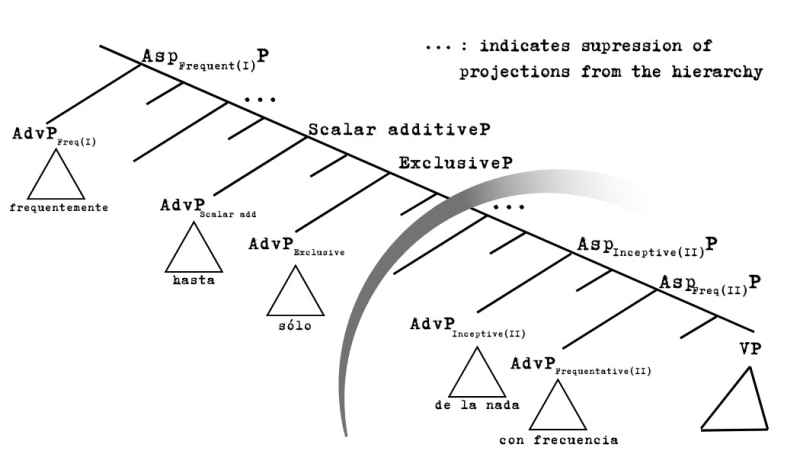

Figure 2 below shows the two positions associated with the frequentative aspect, a category represented in English by the adverbs often and frequently. Given the hierarchy in (6), there is not merely one position for adjuncts modifying the event and one for adjuncts modifying the process (as suggested by the traditional approach described by Figure 1); adverbs are rigidly ordered and what is shown as one position in Figure 1 – e.g., the position whose adjunct modifies the event – has to be seen as a set of positions, rigidly ordered as in (6).

Figure 2: Extract from Cinque’s hierarchy with two AspFrequentative positions

Besides the AspFrequentative category, there is a set of other categories from the hierarchy in (6) which come into two semantically related positions, a point we have already touched upon in the Introduction. This amounts to saying that there are two different positions, each one associated with a distinct category or “class” in the hierarchy, overlapping for some semantic feature. Each “duplicating” category has a different scope in sentence structure, much in the spirit of the representation in Figure 1, from the previous section. Evidence for that comes from sentences like (7), featuring two instances of the AspRepetitive adverb twice. The sentence in (7) is to be interpreted in the following way: “John gave two knocks on the door and that whole event [of twice knocking on the door] took place twice”. If the two instances of twice belonged to the same category, they should not be able to co-occur, given Jackendoff’s (1972) criterion. Furthermore, these two instances of twice are interpreted differently: the one to the left must necessarily take scope over the event while the second, to the right of the V, has to take scope over the process/action of knocking.

| (7) | John twice knocked on the door twice. (Cinque, 1999: 27) |

The duplicating aspectual categories in Cinque’s hierarchy – object of this paper – are AspRepetitive(I) and AspRepetitive(II), AspFrequentative(I) and AspFrequentative(II), AspCelerative(I) and AspCelerative(II), AspInceptive(I) and AspInceptive(II), and, finally, AspSgCompletive(I) and AspSgCompletive(II). Let us now briefly describe one by one.

It is important to recognise – with the tradition in typology (see Comrie, 1976) and with Cinque (1999) – that the main difference between the repetitive and the frequentative aspects consists in the amount of times an event or action is repeated. Hence, while the (two instances of the) repetitive aspect indicate(s) that something took place only twice, or once again, the (two instances of the) frequentative category necessarily imply(ies) that the event or process took place more than twice. Thus, in the latter case, we have an iteration of events or processes. The sentence in (7) just presented illustrates the co-occurrence of two AspRepetitive categories, namely, AspRepetitive(I) and AspRepetitive(II). Below, sentence (8) illustrates the co-occurrence of two instances of the (also) duplicating frequentative adverb.

| (8) | John, wisely, often dates the same person often (Cinque, 1999: 92) |

As in the case of twice, from the example just seen in (7), the two instances of often in (8) have different scopes: the one to the left of the V takes the event under its scope, while the one to the right of the V takes the process under its scope. There is a tradition in Generative Grammar to associate the scope over the event position with adjunction of the adverb to the TP and the scope over the process with adjunction to vP/VP, as sketched in Figure 1 (also see the related text). Once Cinque (1999) realises that each different adverb class from his hierarchy (as seen in (6)) come in a different (specifier) position, the idea behind Figure 1 has to be revisited. Thus, one has to associate scope over the event/the TP – in the spirit of Figure 1 – with Aspxxx(I) and scope over the process/the vP with Aspxxx(II), where the subscripted “xxx” stands for the pairs of duplicating Asp categories.

The categories of AspCelerative refer to the speed in which an event or action takes place. Once again, the (I) and (II) positions differ regarding their scope, with the higher, Asp(I) modifying the event – as in (9) – and the lower, Asp(II) modifying the process – see, for instance, (10).

| (9) | John quickly lifted his arm. (Cinque, 1999: 93) |

| (10) | John lifted his arm quickly. (Cinque, 1999: 93) |

The inceptive aspect marks the beginning of an event/action. It can be filled by adverbials like suddenly and out of the blue. Interestingly enough, these two categories are not filled by the same lexical items in English. As we will see, in BP and in CS, there are specialised items for these two “faces of the same coin” of the inceptive category. (11) and (12) respectively illustrate a sentence featuring the AspInceptive(I) adverb suddenly and a sentence featuring the lower representative of the inceptive category, namely, the AspInceptive(II) adverbial out of the blue.

| (11) | John has suddenly disappeared. (adapted from Cinque, 1999: 208) |

| (12) | Joan Jett plays her guitar out of the blue. (Sant’Anna, 2023: 18) |

Finally, the completive aspect carries the notion of a telic event/process fully achieving its ending point, i.e., an event or process having reached its telos. The hierarchy in (6) makes a distinction between singular and plural completive (aspects): while the first refers either to one object or to each object of a set taken individually, the second refers to a set of objects taken as a whole. Only the singular completive categories are duplicated, thus being of interest in the present study. (13) features the AspSgCompletive(I) category, while (14) illustrates AspSgCompletive(II).

| (13) | John completely forgot her instructions. (Cinque, 1999: 178) |

| (14) | John forgot her instructions completely. (Cinque, 1999: 178) |

As is the case for the other duplicating categories, AspInceptive(I) and AspSgCompletive(I) take scope over the event, while AspInceptive(II) and AspSgCompletive(II) take scope over the action or process.

With this in mind, let us now have a look at seven different tools which can be used to discriminate between each representative of “ambiguous” duplicating adverbs.

2. Diagnostic tools: Data and discussion

In this section, we show seven different diagnostic tools which can be used to discriminate between the two sources or scope positions for each one of the “duplicating” aspectual classes of adverbs – frequentative, repetitive, celerative, inceptive, and completive, as described in the previous section – in clausal structure. Each diagnostic tool can be of help to differentiate the higher source (namely, the position identified by the index (I) from where the adverb has scope over the event) and the lower source (namely, the position identified by the index (II), whose scope is identified as the process). As already said at the very beginning of the paper, we are here drawing our analysis on Cinque’s (1999) cartographic approach. As also said in the previous section, Cinque assumes that adverbs are located in specifiers of distinct maximal projections whose heads match the semantic content of their corresponding specifiers. So, each test has to be interpreted – under Cinque’s cartographic proposal – as indicating whether an adverb is merged in a higher, index (I) position, or in a lower, index (II) one. Of course, approaches turning to more “minimalist” representations in spirit, as the one given in Figure 1, will also benefit from the set of tests presented below as they are indeed also intended to discriminate between the two adverbial sources under scrutiny here.

Before going through the tests, it is important to spell out some preliminary assumptions regarding the methodological démarche to deal with the data. Following the tradition in Generative Grammar, our data has been gathered by introspection. So, the two of us have judged the grammaticality of the sentences – a common practice in Generative Grammar –, the first author being responsible for the data on BP and the second for the data on CS.

From a purely methodological point of view, it is important to note that each sentence composing our corpus must be judged in an out-of-the-blue context – namely, as an answer to questions like the one given in (15) –, so as to guarantee trustworthy minimal pairs.

| (15) | a. | A: | O que aconteceu? | (BP) | |||

| “What happened?” | |||||||

| B: | João | rapidamente | bebeu | a cachaça. | |||

| J. | quickly | drunk | the sugar-cane-brandy | ||||

| “J. quickly drank sugar cane brandy.” | |||||||

| b. | A: | ¿Qué pasó? | (CS) | ||||

| “What happened?” | |||||||

| B: | Juan | rápidamente | se tomó | el pisco. | |||

| J. | quickly | drunk | grappa | ||||

| “J. quickly drank grappa.” | |||||||

This being said, let us now go through each one of the seven tests.

2.1. The relative position of “ambiguous” adverbs with respect to the main Verb

This test is built on the tradition initiated by Emonds (1978) and Pollock (1989). In post-pollockian studies, adverbs are taken to occupy fixed positions in clausal structure. Other constituents, including the main V(erb) and auxiliaries, are taken to raise over these modifiers (see Figure 3 later in the text). Hence, they are considered pivotal-like elements able to identify the position of other constituents in the sentence. This idea, initially developed within Pollock’s approach, has successfully been incorporated into cartographic-like studies that turn to layered representations of the clausal domain. Given that adverbs are rigidly ordered within the clause structure, they serve as precise diagnostics for identifying the various heights which the main verb – as well as other verb forms (e.g., auxiliaries, modals) – can reach within the hierarchy of adverbs outlined in (6) (see Cinque, 1999, Appendix 1; Laenzlinger, 2011; Tescari Neto, 2013, 2025a; Schifano, 2018; Wechsler, 2024).

Since the two languages under investigation exhibit V raising (on BP, see Galves, 1994; Cyrino, 2013; Tescari Neto, 2013, 2020, a.o.; on CS, see Wechsler, 2023), the motivation behind this test is: the maximal height where the V can go may help one discriminate between the two scopal positions. The “template” to be used to diagnose the position of the V relative to adverbs is given in (16).

| (16) | a. | O João | ADV | bebeu | ADV | cachaça | ADV. | (BP) |

| The J. | ADV | drank | ADV | sugar-cane-brandy | ADV | |||

| b. | Juan | ADV | se tomó | ADV | pisco | ADV. | (CS) | |

| J. | ADV | CL took | ADV | grappa | ADV | |||

| “J. drank sugar cane brandy/grappa.” | ||||||||

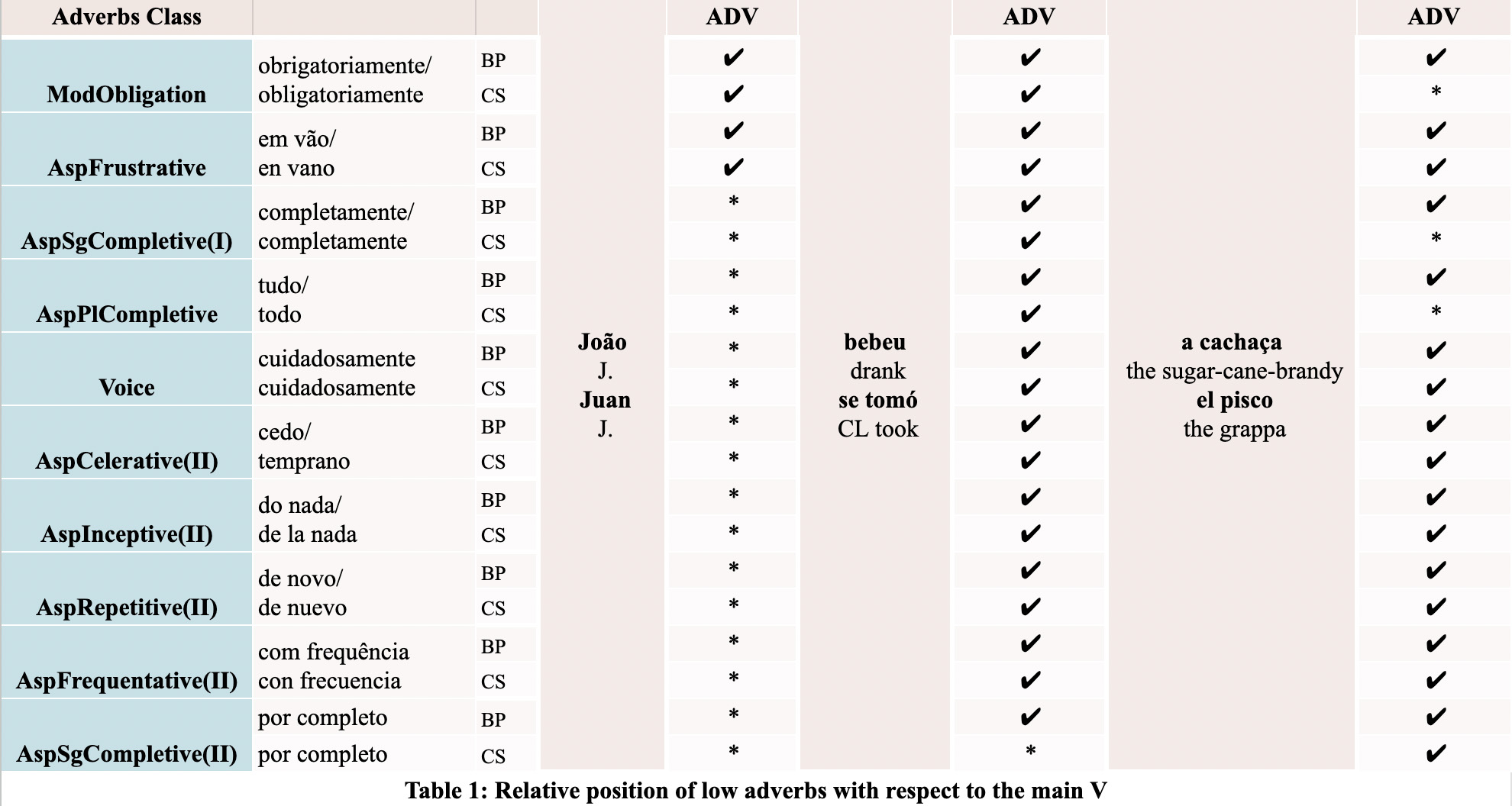

As shown by (16), three surface positions for adverbs are worth testing: the position to the right of the direct object (cachaça (a)/pisco (b)), the position between the main V and its object, and the pre-verbal position. As stated in the Introduction, PPs can only be merged in the lower position in BP and in CS. See also Section 2.2, as well as the paragraphs preceding the data in (3) in the Introduction, for a discussion on the specialisation of PPs and adverbs ending in -mente for specific positions (Asp(I) and Asp(II)) in these two languages.

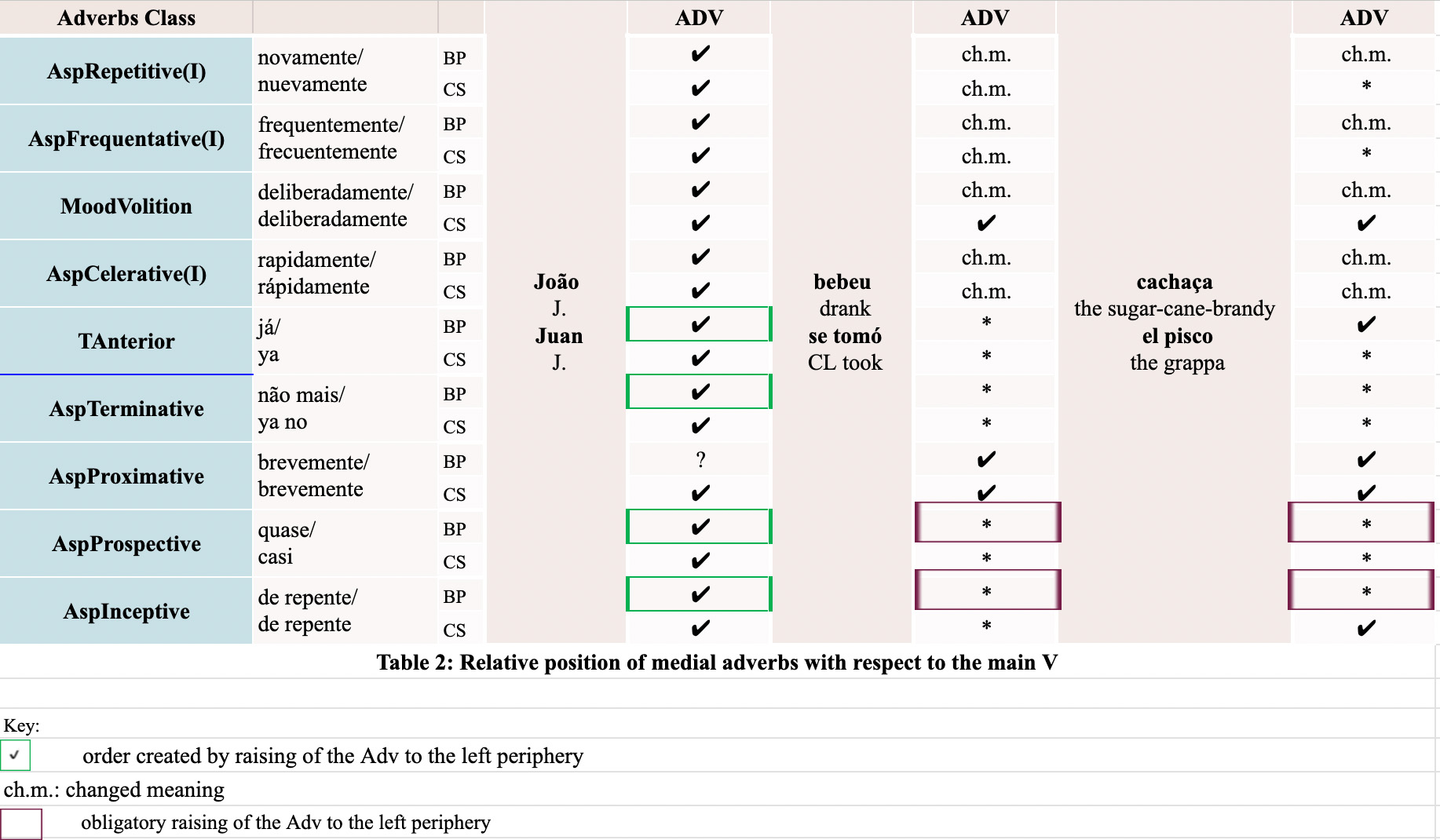

Now, the expected scenarios for BP and CS are those described in the sequence. In BP, given that the main V performs optional V raising among medial adverbs – see the data in Table 2 of the Appendix –, one expects that “duplicating” adverbs ending in -mente can fill both the high, Asp(I), and the low, Asp(II), positions, while PPs can only fill the two positions to the right of the V in the template in (16). When it comes to CS, things are even clearer as the only position which can be filled by adverbs ending in -mente is the one to the left of the V, the positions to the right of the V only accepting PPs. This prediction is actually borne out by the data. Below, we illustrate this test: example (17) features a low adverb as a representative of the Asp(II) class; example (18) features a medial adverb as a representative of the Asp(I) class.

| (17) | a. | O João | (*de novo) | bebeu | (de novo) | cachaça | (de novo). | (BP) |

| The J. | again | drank | again | sugar-cane-brandy | again | |||

| b. | Juan | (*de nuevo) | se tomó | (de nuevo) | pisco | (de nuevo). | (CS) | |

| J. | again | CL took | ADV | grappa | ADV | |||

| “J. drank sugar cane brandy/grappa.” | ||||||||

| (18) | a. | O João | (novamente) | bebeu | CM(novamente) | cachaça | CM(novamente). | (BP) |

| The J. | again | drank | again | sugar-cane-brandy | again | |||

| b. | Juan | (nuevamente) | se tomó | CM(nuevamente) | pisco | (*nuevamente). | (CS) | |

| J. | again | CL took | ADV | grappa | ADV | |||

| “J. drank sugar cane brandy/grappa.” | ||||||||

While only adverbs ending in -mente can fill higher, Asp(I) positions – see the ungrammaticality of the order PP (de novo/de nuevo ‘again’)-V in (17) and the grammaticality of the order adverb in -mente-V in (18a) –, PPs can fill post-verbal positions in both languages – see (17), where de novo/de nuevo (‘again’) can appear in the two positions to the right of the V. Adverbs ending in -mente are totally fine in the two post-verbal positions in BP (see (18a)), but with a change in their meaning (which is indicated by the superscripted CM in the examples): when linearised post-verbally, the ending in -mente adverb modifies the process, being a representative of the Asp(II) category; in this case, adverbs ending in -mente do not have access to the higher position of merger – only Asp(I) adverbs can be merged there. Thus, in post-verbal positions, it is the Asp(II) projection that is activated and, therefore, the adverb merged there is the one to be linearised. Evidence from this conclusion comes from CS: only PPs are allowed in post-verbal positions. This indicates that one must assume distinct scopal positions, one lower and one medial in the structure. Regarding the other six classes of “duplicating” adverbs, we refer the reader to Tables 1 and 2 from our Appendix. The pattern presented is the same for the other classes.

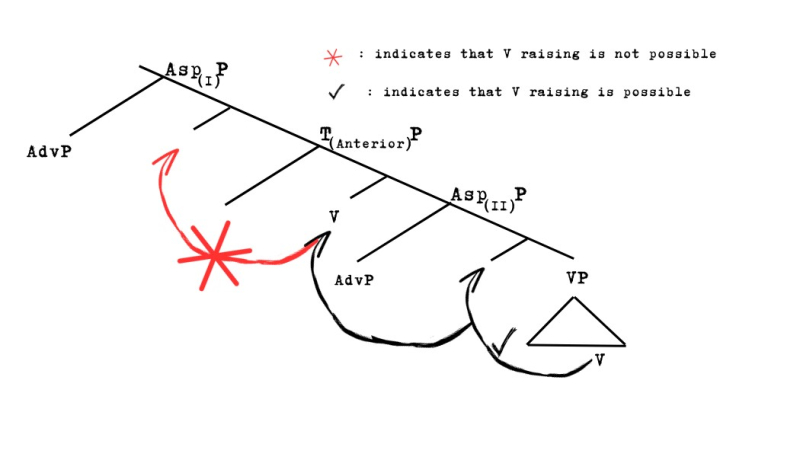

Figure 3: Verb Raising as a diagnostic for the Asp(I)/Asp(II) distinction

Taking the relative position of the Asp(I)/Asp(II) adverb with respect to the V is convincingly a reliable test in BP and in CS to discriminate between the two adverbial sources. While the main, finite V must raise over all Asp(II) adverbs – and optionally over some medial adverbs –, it cannot raise over medial Asp(I) adverbs (see Figure 3 and Tables 1 and 2), reason why adverbs ending in -mente in post-verbal positions change their meaning in BP. This “changing in meaning” is only epiphenomenal: it is no longer the higher, Asp(I) position which is linearised, but the lower, Asp(II) one. Therefore, one can take this test as a bona fide diagnostic at least in BP and CS, given the obligatory raising of the main V across the lower portion of the clause in both languages.

2.2. The morphological nature of ambiguous adverbs

As already mentioned in the Introduction, natural languages may vary regarding the realisation of duplicating aspectual categories either by the same lexical item or by different, specialised items. Examples (1) and (2) (from the Introduction) show that, while Italian has different lexical items for the higher and lower AspRepetitive positions, English only counts on one same lexical item for both positions. For a more thorough discussion on this important cross-linguistic variation matter, see Cinque (1999, 2004).

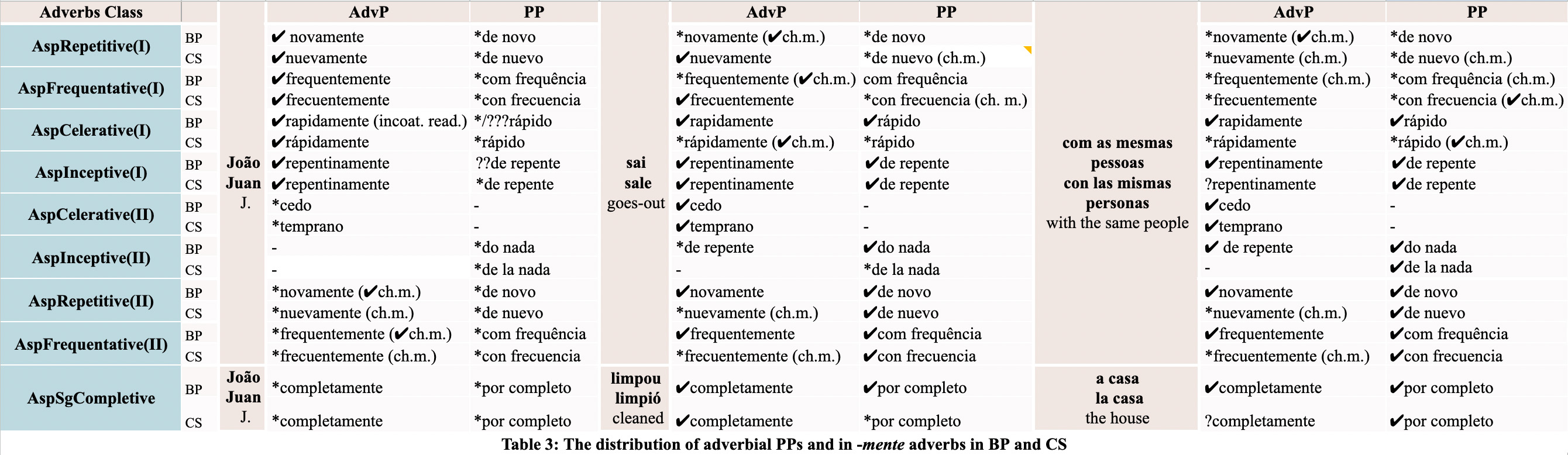

In BP and CS, “duplicating” adverbial categories may be realised by an AdvP ending in -mente (like novamente/nuevamente ‘again’, for example) and/or by a PP (like de novo/de nuevo ‘again’).6 Considering some languages’ lexical distinction for duplicating categories, our aim with this test is to determine which morphological form(s) – AdvP in -mente and/or PP (P + NP) – can occupy each aspectual category and whether the morphophonological realisation of an adverbial can help us distinguish the higher from the lower duplicating categories.

For this diagnosis, we turn to sentences like (19)‑(20) featuring the two possible morphological realisations (namely, AdvP in -mente and/or PP) appearing before – therefore, in the higher (I) position (see (19)) – and after the Verb– in the lower (II) position (see (20)).

| (19) | AspRepetitive(I): | ||||

| a. | João | novamente/*de novo | serviu | todos os pratos. | (BP) |

| J. | again | filled | all the plates | ||

| b. | Juan | nuevamente/*de nuevo | sirvió | todos los platos. | (CS) |

| J. | again | filled | all the plates | ||

| “J. once again filled everybody’s plates.” | |||||

| (20) | AspRepetitive(II): | ||||

| a. | João | serviu | novamente/de novo | todos os pratos. | (BP) |

| J. | filled | again | all the plates | ||

| b. | Juan | sirvió | ??nuevamente/de nuevo | todos los platos. | (CS) |

| J. | filled | again | all the plates | ||

| “J. filled again everybody’s plates” | |||||

| (20’) | AspRepetitive(II): | ||||

| a. | João | serviu | todos os pratos | novamente/de novo. | (BP) |

| J. | filled | all the plates | again | ||

| b. | Juan | sirvió | todos los platos | *nuevamente/de nuevo. | (CS) |

| J. | filled | all the plates | again | ||

| “J. filled again everybody’s plates” | |||||

This test demonstrates that the higher (I) category can only be lexicalised by an ending in -mente AdvP, while the lower (II) category can only be realised by a PP in CS and preferentially by a PP in BP, though either form for the (II) category is possible in this latter language – as already stated in previous sections. The results for other aspectual categories can be found in Table 3 from our Appendix.

Given that different categories occupy different positions, this seems to be a matter of structure, i.e., of how Narrow Syntax (NS) maps out different structures to the interface systems – here, the conceptual-intentional system – to be interpreted. The morphological nature of the adverbial can therefore be useful in discriminating duplicating positions and proves to be a trustworthy diagnostic to disambiguate same-aspect adverbs (specially for CS and for adverbial PPs in BP).

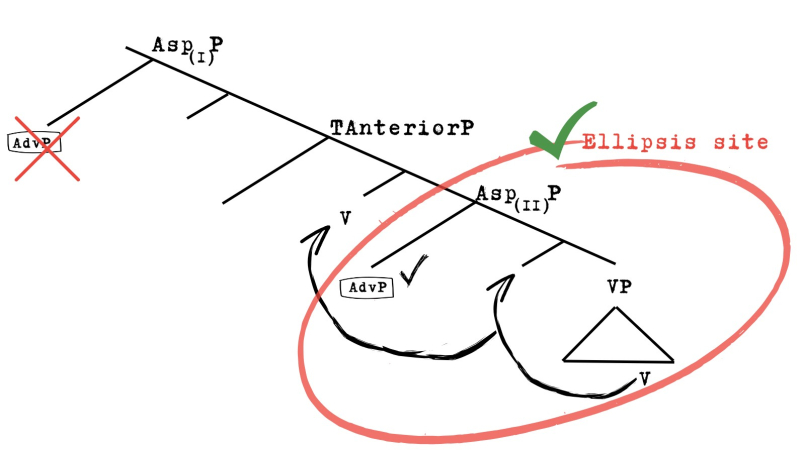

2.3. The recovery of an adverb by the elliptical VP

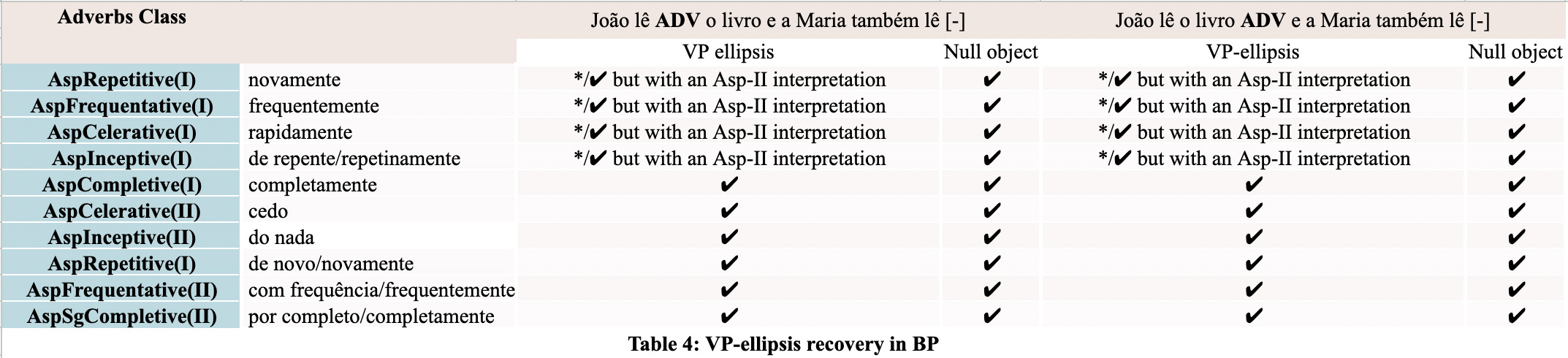

Another diagnostic tool to discriminate between the two scope positions is VP ellipsis. This test is only useful for BP, since this language exhibits this phenomenon while Spanish does not (see Matos and Cyrino, 2001; Cyrino and Matos, 2002). Given that the finite main V can go up to TAnterior in BP (Tescari Neto, 2013), the recovery of adverbs below TAnterior by the gap in coordinated structures giving rise to VP ellipsis is possible. Thus, the main motivation for this test is that, since VP ellipsis is dependent on V raising, which is limited in BP – the main V cannot raise over Asp(I) adverbs (which are, with the exception of the AspSgCompletive(I) completamente ‘completely’, above TAnterior) –, it can be used to discriminate between the two scopal positions: the only possible recovery of adverbs –by the gap in coordinated structures giving rise to VP ellipsis – is the recovery of Asp(II) adverbs. This prediction is borne out by the data.

| (21) | The recovery of Asp(II) adverbs by the gap (see the interpretation in (i)) in coordinated structures giving rise to VP ellipsis constructions is possible: | ||||

| João | bebe | cachaça | com frequência | (BP) | |

| J. | drinks | sugar-cane-brandy | with frequency | ||

| e a Maria | também | bebe | [-]. | ||

| and the M. | also | drinks | [-]. | ||

| “J. frequently drinks sugar cane brandy and so does Maria.” | |||||

| (i) | [-]: OKdrinks sugar cane brandy frequently. | ||||

| (ii) | [-]: OKsugar cane brandy. | ||||

| (22) | The recovery of Asp(I) adverbs by the gap in coordinated structures giving rise to VP ellipsis constructions is not possible (see the interpretation in (i)): | ||||

| João | frequentemente | bebe | cachaça | (BP) | |

| J. | frequently | drinks | sugar-cane-brandy | ||

| e a Maria | também | bebe | [-]. | ||

| and the M. | also | drinks | [-] | ||

| “J. frequently drinks sugar cane brandy and so does Maria.” | |||||

| (i) | [-]: *drinks sugar cane brandy frequently. | ||||

| (ii) | [-]: OKsugar cane brandy. | ||||

While the recovery of an Asp(II) adverb by the gap in VP ellipsis constructions is possible – see the interpretation suggested by (21i) for the gap ([-]) in (21) –, such a recovery is not possible for Asp(I) adverbs (see (22i)), at least in BP. This is so because the maximum height of movement for the V in BP is TAnterior, a position below the Asp(I) positions in the hierarchy in (6). The only exception is the AspSgCompletive(I) completamente (‘completely’), which is lower than TAnterior. As such, the recovery of this adverb by the gap is possible.

Data featuring the other adverbs is shown in Table 4 in the Appendix. Recovery by the gap in coordination structures like (21‑22) giving rise to VP ellipsis is possible to each adverb below TAnterior. This is illustrated by Figure 4, which shows that below TAnterior, say, below the elliptical site, there are only Asp(II) adverbs. Recovery of these adverbs by the gap in coordination structures giving rise to VP ellipsis is possible. Therefore, VP ellipsis is a useful diagnostic, at least in BP.

Figure 4: VP ellipsis as a diagnostic for the Asp(I)/Asp(II) distinction in BP

2.4. The placement of an adverb(ial) in the structure “Infinitival Subject Clause” + Small Clause

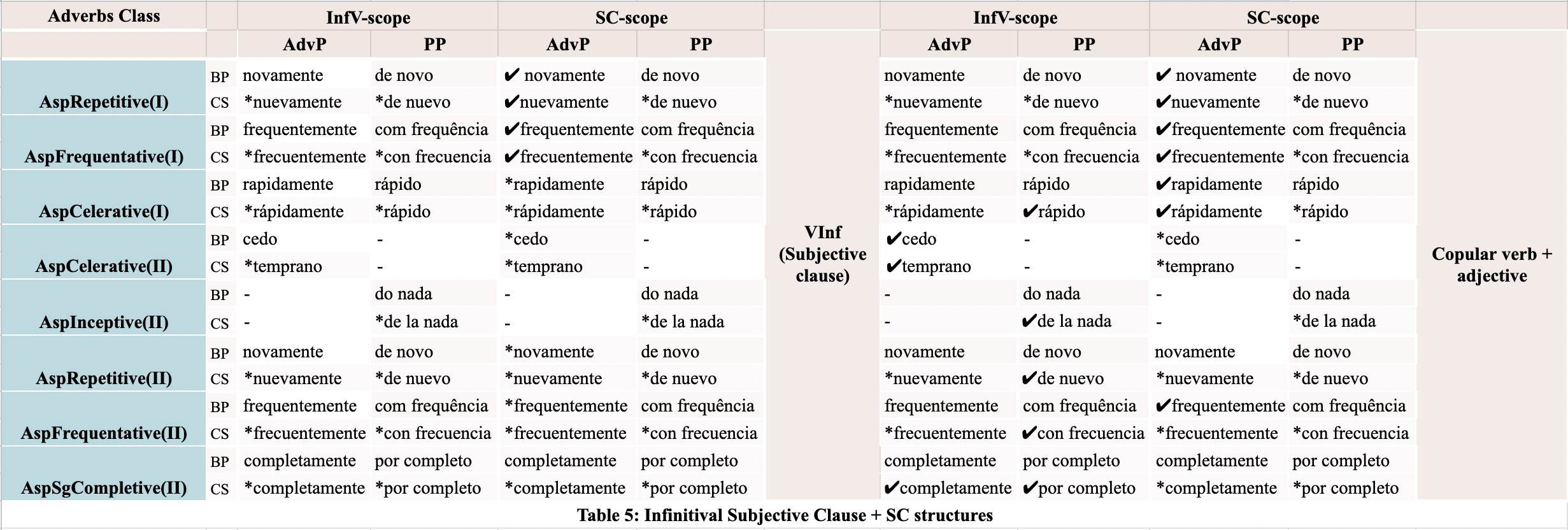

For this test, we take small clauses (SC from now on)—like Correr é bom/Correr es bueno ‘To-run is good’—formed by a copular verb (é/es ‘to be’ in this example) and having an Infinitival Subject Clause (Correr/correr ‘to run’) as its subject. In these biclausal structures, adverbs can modify either the finite copular verb or the infinitival verb (InfV, henceforth). The aspectual adverb(ial) is placed to the left of the InfV or to its right. With these sentences, it is possible to play with two distinct syntactic domains, or CPs, each one potentially having different heights for the raising of the infinitival V, on the one hand, and for the raising of the finite copular V, on the other. This also allows one to more clearly test differences in scope regarding the duplicating categories, since, as we will see, different lexicalisations – PP adverbials and AdvPs in -mente – can result in different readings, even when the adverbials occupy the same linear position (though not the same structural position, thus resulting in the different readings).

The sentences in ((23)‑(26)) below, featuring the AspFrequentative categories in both languages, illustrate this expedient. Now, for each sentence, there are two possible readings: (i) the adverbial modifies the infinitival verb, meaning that “It’s good [to run often]”; (ii) the adverbial modifies the copular verb, meaning that “[It’s often good] to run”. The grammaticality of the sentences is provided separately for each of these readings.

| (23) | AspFrequentative(II): | ||||

| a. | Correr | com frequência | é bom. |

(i) ✓It’s good [to run often]. (ii) *[It’s often good] to run. |

(BP) |

| To-run | often | is good | |||

| b. | Correr | con frecuencia | es bueno. |

(i) ✓It’s good [to run often]. (ii) *[It’s often good] to run. |

(CS) |

| To-run | often | is good | |||

| (24) | AspFrequentative(II): | ||||

| a. | Com frequência *(,) | correr | é bom. |

(i) *It’s good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It’s often good] to run (only if the adverb is left-dislocated). |

(BP) |

| Often | to-run | is good | |||

| b. | Con frecuencia *(,) | correr | es bueno. |

(i) *It's good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It's often good] to run (only if the adverb is left-dislocated). |

(CS) |

| Often | to-run | is good | |||

| (25) | AspFrequentative(I): | ||||

| a. | Correr | frequentemente | é bom. |

(i) ✓It’s good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It’s often good] to run (preferential reading). |

(BP) |

| To-run | often | is good | |||

| b. | Correr | frecuentemente | es bueno. |

(i) ?It’s good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It’s often good] to run. |

(CS) |

| To-run | often | is good | |||

| (26) | AspFrequentative(I): | ||||

| a. | Frequentemente | correr | é bom. |

(i) *It’s good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It’s often good] to run. |

(BP) |

| Often | to-run | is good | |||

| b. | Frecuentemente | correr | es bueno. |

(i) *It’s good [to run often]. (ii) ✓[It’s often good] to run. |

(CS) |

| Often | to-run | is good | |||

In (23), the low Asp(II) adverbials com frequência/con frecuencia can only modify the InfV correr, which occupies a higher position. They cannot take under their scope the copular V é/es, since the finite V must obligatorily raise to a position higher than AspFrequentative(II). This shows that com frequência/con frecuencia is indeed merged in a low position in the hierarchy and must be within the domain of the InfV in order to generate the sentences in (23).

The low Asp(II) adverbials can appear in the beginning of the sentence, as in (24), when they are left-dislocated – as indicated by the comma, which suggests that the left-dislocated adverbials are also prosodically set-off from the rest of the sentence. In this case, the only possible reading is (ii): the adverbial only modifies the copular sentence as a whole. The adverbial PP must then be externally merged in the Asp(II) position below the main V and subsequently raised to a left-peripheral-like position in the CP domain. It cannot modify the InfV, which also raises obligatorily above the AspFrequentative(II) position.

The AdvPs frequentemente and frecuentemente (‘often’) are tested in the sentences in (25), in which the adverb appears above the main copular V and can thus modify it (as already predicted – see Section 2.1). Here, there is some cross-linguistic variation considering the two languages under study, which was already expected taking into account the fact that in -mente adverbs are underspecified in BP – thus occupying either the (I) or the (II) position – but not in CS. That explains why (25a) can have both of the intended readings (even though the second one is preferred), while the reading in (i) is marginal for (25b).

Finally, the AdvP can be externally merged above the InfV – without the need for left-dislocation, unlike (24) –, as shown in (26). In these sentences, the only possible reading is (ii), whereby the adverb modifies the finite copular V – thus being merged within the Infinitival Subject Clause. This test was also applied to the other aspectual duplicating categories, and the results can be found in Table 5 in the Appendix.

The structure discussed in this section – i.e.,“Infinitive Subject Clause” + SC – can help one discriminate between Asp(I) and Asp(II) adverbials, either by their position relative to the V(s) or by their scope. Based on the BP and CS data, it is plausible to ascertain that only Asp(I) adverbs in -mente can appear before the InfV, necessarily taking the SC under their scope (reading (ii)). Both Asp(I) adverbs and Asp(II) adverbials can occur between the InfV and the copular V. However, in this position, the Asp(I) adverb can only take the SC under its scope in CS; this is also the preferential setting in BP. The Asp(II) adverbial, on the other hand, can only modify the InfV in both languages when linearised before the finite copular verb.

2.5. The appearance of an adverb(ial) in interrogatives

Studies on the syntactic-semantic properties of high, “sentential” adverbs (mainly influenced by Bellert, 1977) have shown that some classes of adverbs cannot appear in interrogative sentences. This is particularly the case of modal adverbs, as shown by (27).

| (27) | *Has/Will John probably/certainly/evidently come? (Bellert, 1977: 344) |

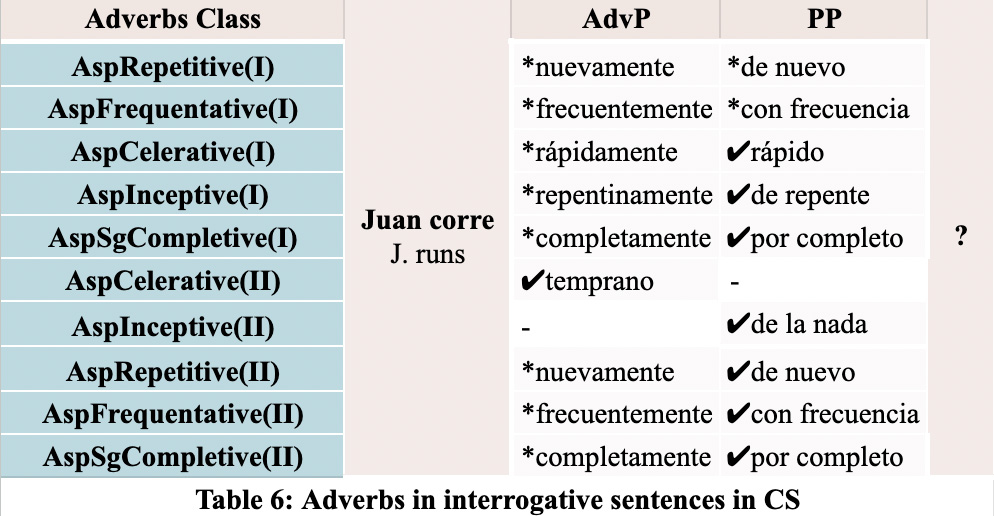

Cross-linguistically, this property seems to be language-dependent, insofar as the “watershed” in the hierarchy (in (6)) dividing it in two portions – a higher portion and a lower one – seems to be open to parametric variation (see Tescari Neto, 2025b). While in English high, sentence adverbs (mainly modal adverbs) cannot appear in interrogatives (27), AspFrequentative(I) adverbs can (which is the case of often in (28)). The same class of AspFrequentative(I) adverbs, on the other hand, seem to behave like high, sentence adverbs in CS with respect to this property (see (30b) below). Since this test is useful in the identification of higher adverbs, and, in BP, AdvPs ending in -mente are underspecified and can occupy both the high and low duplicating positions (see Section 2.2), the data and results from this section only apply to CS.

| (28) | Does John often come here? (Bellert, 1977: 341) |

CS patterns like English with respect to the ill-formedness of an interrogative sentence featuring a modal adverb (see (29), the CS correspondent of (27)).

| (29) | *Juan | probablemente/seguramente/evidentemente | va a venir? | (CS) |

| J. | probably/certainly/evidently | will come | ||

| “Will J. probably/certainly/evidently come?” | ||||

Nonetheless, CS behaves differently with respect to the appearance of an AspFrequentative(I) adverb in an interrogative sentence, insofar as this structure is also reported as ungrammatical (see (30b)). AspRepetitive(I) adverbs cannot appear in interrogative sentences in CS either (see (31b)), suggesting that the height where the hierarchy must be cut off – thus separating high/sentence adverbs from low adverbs – varies cross-linguistically.

With that in mind, one can take advantage of these facts in CS to see whether they can discriminate between the two sources for duplicating adverbs: it is expected that only Asp(II) adverbs can appear in interrogative sentences, while their Asp(I) mates simply cannot. This is actually borne out by the data in (30) and (31): only Asp(II) adverbs (see (30a) and (31a)) are allowed in interrogative sentences; Asp(I) are forbidden in this sentential type (see (30b) and (31b)).7

| (30) | AspFrequentative: | |||

| a. | Juan | corre | con frecuencia? | (CS) |

| John | runs | often | ||

| “Does John run often?” | ||||

| b. | *Juan | corre | frecuentemente? | (CS) |

| John | runs | often | ||

| “Does John run often?” | ||||

| (31) | AspRepetitive: | |||

| a. | María | se vacunó | de nuevo? | (CS) |

| Mary | got vaccinated | again? | ||

| “Did Mary get vaccinated again?” | ||||

| b. | *María | se vacunó | nuevamente? | (CS) |

| Mary | got vaccinated | again? | ||

| “Did Mary get vaccinated again?” | ||||

From the sentences above – and others, displayed on Table 6 in the Appendix – it can be concluded, for CS only – since this language makes a clear distinction between adverbs filling the two scopal positions –, that this test helps one distinguish which scopal position is activated: the higher or the lower.

2.6. Adverb(ial) under the scope of a focusing-like adverb

Some of the tests applied by Haegeman (2012) and Souza de Paula (2022) to discriminate Central Adverbial Clauses (CACs) – modifying the VP – from Peripheral Adverbial Clauses (PACs) – modifying higher portions of the structure – can be extended to adverb(ial)s, in the spirit of Duplâtre and Modicom (2022). Similarly to Adverbial Clauses, adverbs and adverbials can either be VP-related (like CACs) or occupy higher positions.

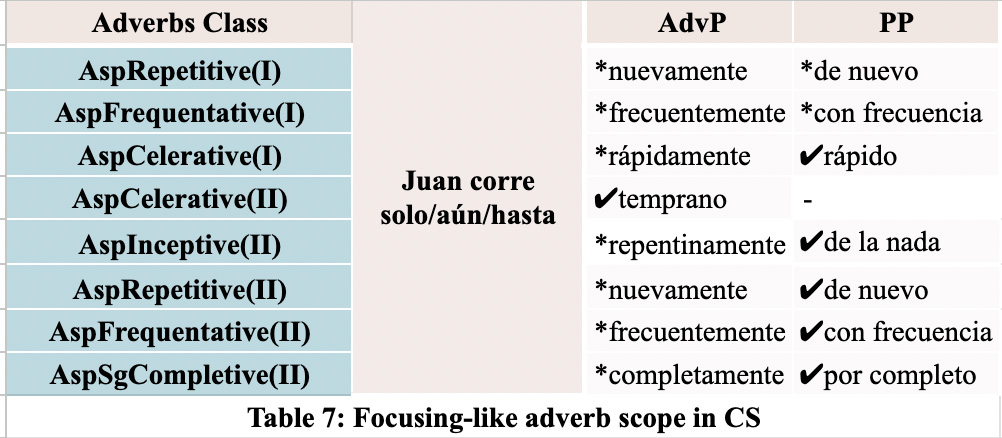

In this section we turn to Haegeman’s (2012) and Souza de Paula’s (2022) test featuring adverbs which may associate with the sentence focus (the so-called “focusing adverbs” – see, a.o., Quirk et al., 1976; Ilari, 1992; Ricca, 1999; Andorno, 2000; De Cesare, 2010; Ferrari et al., 2011; Tescari Neto, 2025b). The motivation for this is that focusing adverbs occupy IP-internal positions which are above all Asp(II) adverbs—and the AspSgCompetive(I) completamente “completely”—but below the positions occupied by Asp(I) adverbs (see Tescari Neto, 2017, 2025b). Only adverb(ial)s from categories lower than the focusing ones – thereby c-commanded by them – can fall under the scope of a focusing-like adverb. This test can therefore be adapted in order to discriminate lower, process modifying adverbial categories from higher, event modifying ones. See Figure 5 for the positions occupied by the classes of focusing adverbs directly associated with this test.

Since this test only helps one identify modifiers occupying lower positions, which are lexically underspecified in BP – adverbs in -mente being compatible with both Asp(I) and Asp(II) positions in this language (see Section 2.2) –, it is most useful for CS data, even though we have found that the PP form is preferred to AdvPs in -mente in BP.

The elaborated sentences consist of a structure containing a focusing-like adverb and an aspectual adverb or adverbial under its scope. Only categories lower than the focusing adverbs can be focalized, thus forming a constituent with them. Sentences (32) and (33) illustrate some of the tests featuring different categories of aspectual and focusing-like adverbs.

| (32) | AspFrequentative: | |||

| a. | Juan corre | solo | con frecuencia. | (CS) |

| John runs | only | often. | ||

| “John only runs often.” | ||||

| b. | *Juan corre | solo | frecuentemente. | (CS) |

| John runs | only | often. | ||

| “John only runs often.” | ||||

| (33) | AspInceptive: | |||

| a. | Juan corre | hasta | de la nada. | (CS) |

| John runs | even | out of nowhere. | ||

| “John even runs out of nowhere.” | ||||

| b. | *Juan corre | hasta | repentinamente. | (CS) |

| John runs | even | out of nowhere. | ||

| “John even runs out of nowhere.” | ||||

The tests have indicated that only adverb(ial)s c-commanded by “focusing” adverbs – i.e., those placed below the positions occupied by focusing adverbs – can be under the scope of these focalisers. All classes of Asp(II) adverbs are below focusing adverbs (see Figure 5), and can therefore be under their scope. Since Asp(I) adverbs are above focusing adverbs, they cannot fall under the scope of these focalisers. This is represented in Figure 5, in which the half moon is intended to show the categories which can fall under the scope of focusing adverbs, say, only the categories c-commanded by them. Asp(I) adverbs, being above focusing adverbs, cannot fall under their scope, the reason why (32b, 33b) are ungrammatical. For the data featuring the other Asp(I) and Asp(II) adverbs, see Table 7 in the Appendix. For details on the categories of focusing adverbs used here as diagnostics and their position relative to other classes of Cinque’s (1999) adverbs, see Tescari Neto (2025b).

Figure 5: The position of Asp(I) and Asp(II) adverbs relative to focusing adverbs

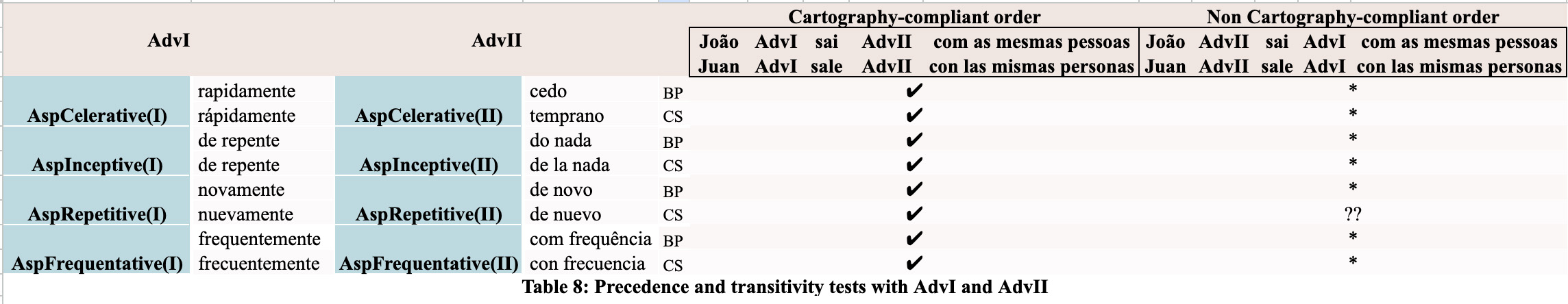

2.7. Precedence-and-transitivity tests

Syntactic Cartography counts on precedence-and-transitivity tests as one of its most important methodological tools in order to arrive at the hierarchies or f-seqs for clause structure and other distinct domains – e.g., the extended projection of the nominal phrase, that of adjectives, PPs, etc. Therefore, this type of test can also be used to discriminate between the two “ambiguous” positions, namely, the one associated with Asp(I) and the one associated with Asp(II). In this scenario, we can play with at least three distinct “contexts” to see if an adverb in a given sentence originates from the Asp(I) or the Asp(I) source:

| (i) | a high adverb co-occurring with an adverb-Asp(I) (in the two possible orders); |

| (ii) | an adverb-Asp(I) co-occurring with an adverb-Asp(II) (in the two possible orders); |

| (iii) | an adverb-Asp(II) co-occurring with an even lower adverb (in the two possible orders). |

Here, we will be focusing on the context indicated in (ii). Context (i) does not effectively help discriminate between the two scopal positions, as a high adverb precedes both an adverb-Asp(I) and an adverb-Asp(II). Moreover, context (ii) is enough to discriminate between the two scopal sources or positions, thus rendering context (iii) unnecessary.

The main motivation for this test is that, according to many works in Syntactic Cartography, functional categories are rigidly ordered in the sentence.8

Let us thus apply the precedence expedient, considering the context in (ii) above. We are verifying the relative position of an adverb-Asp(I) with respect to an adverb-Asp(II) (in the two possible orders). Here, we will use the AspCelerative(I) rapidamente/rápidamente ‘quickly’ to co-occur with the AspCelerative(II) cedo/temprano ‘early’ in the two possible orders.9,10

| (34) | Asp(I) adverb (AspCelerative(I)) > Asp(II) adverb (AspCelerative(II)): | |||||

| a. | João | rapidamente | sai | cedo | com as mesmas pessoas. | (BP) |

| J. | quickly | goes-out | early | with the same people | ||

| b. | Juan | rápidamente | sale | temprano | con las mismas personas. | (CS) |

| J. | quickly | goes-out | early | with the same people | ||

| “J. quickly goes out with the same people early.” | ||||||

| (34’) | Asp(II) adverb (AspCelerative(II)) > Asp(I) adverb(AspCelerative(I)): | |||||

| a. | *João | cedo | sai | rapidamente | com as mesmas pessoas. | (BP) |

| J. | early | goes-out | quickly | with the same people | ||

| b. | *Juan | temprano | sale | rápidamente | con las mismas personas. | (CS) |

| J. | early | goes-out | quickly | with the same people | ||

| “Early J. goes out with the same people quickly.” | ||||||

Only the data in (34) gives rise to well-formed results, inasmuch as they represent the hierarchical order, i.e., the one licensed by the hierarchy in (6). We can take the precedence expedient as a way to discriminate between the two sources for the placement of duplicating adverbs, therefore concluding that their ambiguity is much more apparent than real, as they have access to two areas in the structure of the clause. For the data exploring the same test on the other Asp(I) and Asp(II) classes, see Table 8 in the Appendix.

In a nutshell, precedence-and-transitivity tests help one discriminate between the two sources for allegedly ambiguous adverbs. The high “duplicating” (Asp(I)) categories must precede the low duplicating ones (Asp(II)). No change in meaning is possible to “save” the grammaticality of the sentence if we take into account the PP as representative of the Asp(II) class.

3. A syntactic way to interpret the results

Throughout Section 2 we have seen that (i) the highest position can only be filled by adverbs ending in -mente in BP and in CS; (ii) the lowest adverbial position can be filled either by adverbs ending in -mente or (preferentially) by PPs in BP; only PPs are allowed in the lowest position in CS; (iii) when it comes to lower adverbs we do find an interesting cross-linguistic variation between the two languages; (iv) the tests presented are trustworthy tools to discriminate between the two scopal positions.

The main results are summarised in the following table.

Summary Table: Diagnostic tools: Summing up the main findings

| Test | BP | CS | Conclusion |

| 1. The relative position of the so-called “ambiguous” adverbs w.r.t. the main V | ✔ | ✔ | In both languages, Asp(II) adverbs are below the minimum height occupied by the finite V. |

| 2. The morphological nature of the ambiguous adverb | ✔ | ✔ |

Asp(I) adverbs: -mente (BP, CS); Asp(II) adverbs: -mente (BP); PPs (BP, CS). |

| 3. The recovery of an adverb by the elliptical VP | ✔ | Doesn’t apply | Recovery by the gap in VP ellipsis is possible only for Asp(II) adverbs and the AspSgCompletive(I) completamente ‘completely’ but not for Asp(I) adverbs. |

| 4. The placement of an adverbial in the structure “Infinitival Subject Clause + Small Clause” | ✔ | ✔ | Asp(I) adverbs take the SC under their scope; Asp(II) adverbs take the InfV under their scope. |

| 5. The appearance of an adverb(ial) in interrogative sentences | Doesn’t apply | ✔ | Only PPs (belonging to the lower categories) can appear in interrogatives. |

| 6. Adverb(ial) under the scope of a focusing-like adverb | Doesn’t apply | ✔ | Only PPs (from the lower categories) can fall under the scope of a focusing adverb |

| 7. Precedence-and-transitivity tests | ✔ | ✔ | In both languages, high adverbs precede Asp(I) adverbs; Asp(I) adverbs precede Asp(II) adverbs. |

Tests 1, 2, 4, and 7 can be applied both to BP and CS and are reliable tools to discriminate between the two sources, namely, the set of Asp(I) positions, on the one hand, and the set of Asp(II) positions, on the other. Considering the two languages under scrutiny here, we have observed some cross-linguistic variation regarding the behaviour exhibited with respect to the construction or phenomenon behind each test. Hence, when it comes to the morphological nature of the candidates filling the Asp(I) and the Asp(II) positions, while Asp(I) adverbs are realised by an ending in -mente AdvP both in BP and in CS, there is variation regarding the realisation of Asp(II) adverbs: an ending in -mente form can only appear in BP, while PPs are possible in both languages, being the only alternative in CS – see the second line of the table.

Still regarding cross-linguistic variation, the fifth and the sixth tests only apply to CS, inasmuch as this language morphologically discriminates the two scopal positions, as just mentioned. Since these two tests – though syntactic in nature – depend on morphological distinctions to be valid, they are only useful for CS. Consequently, languages morphologically discriminating between these two scopal positions – thus, with specialised lexical items for each position – may also benefit from the tests with interrogative sentences and focusing-like adverbs. On the other hand, the third test is only useful for BP, since this language allows VP ellipsis. Recovery by the gap in coordinated structures giving rise to VP ellipsis is only possible for Asp(II) adverbs and AspSgCompletive(I) completamente ‘completely’, inasmuch as they are below the highest position the finite V can occupy in BP. Thus, the test helps one discriminate between the two scopal positions for “ambiguous” adverbs in BP – and other languages that feature VP ellipsis.

Finally, we have seen that the suggested tests are trustworthy tools to discriminate between Asp(I) and Asp(II) adverbial categories. Besides that – and now sticking our guns to the theoretical framework adopted –, since there is a direct map from Narrow Syntax to the conceptual-intentional interface, the position where allegedly ambiguous adverbs enter the structure is highly structurally constrained. This amounts to saying that ambiguous duplicating aspectual adverbs are only apparently ambiguous. Therefore, there is no such ambiguity on structural grounds.

In guise of conclusions

We saw in Section 2 seven distinct configurations which may be taken as diagnostic criteria to discriminate between Asp(I) and Asp(II) adverbs. The idea behind those seven criteria is: the Asp(I) – Asp(II) distinction is a reflection of the hierarchical structure where different classes of adverbs are rigidly ordered. Therefore, every syntactic process sensitive to this hierarchy may be taken into account as a potential means to distinguish these two sets of syntactic positions.

The seven tests seen proved to be useful diagnostic tools. Although languages may opt for using the same lexical items in the two Asp(I)/Asp(II) scopal positions – and this is the case of ending in -mente adverbs in BP, which can have access to both of these sources (see Sections 2.1 and 2.2) –, languages may also specialise for the two scopal positions. This is the case for CS: adverbs ending in -mente can only occupy the higher Asp(I) positions, while the equivalent PPs only have access to the lower, Asp(II) positions. This interesting cross-linguistic variation is reflected in the set of tests explored here.

Interestingly enough, though in BP PPs can only enter the lower, Asp(II) positions, it is possible to take advantage of the tests just seen to identify in which of the two sources a given ending in -mente adverb is merged/enters the derivation. Thus, besides helping us argue that the ambiguity of these alleged ambiguous, duplicating adverbs is only epiphenomenal – as there is indeed no ambiguity on syntactic grounds –, these seven tests are reliable tools to help one identify which syntactic position (the one associated with the event, hence the Asp(I) position, or the one associated with the process, hence, the Asp(II) one) is the one being occupied by the (allegedly) “ambiguous” adverb in a given sentence.

Furthermore, since each of these tests have specific syntactic motivations – most of them sensitive to language-internal properties –, as shown throughout dedicated subsections in Section 2, they are good tools to approach microparametric properties of the languages under study, an important issue within the agenda of the Principles and Parameters Theory.

Finally, given that, under each “Asp(I)” and “Asp(II)” set there is a series of different semantic aspectual categories, rigidly ordered within a f(unctional)-sequence (the hierarchy shown in (6)), the conclusions reached in this paper favour layered representations of the clause as is the norm in approaches turning to fine-grained configurations, such as Syntactic Cartography. Though the paper was drawn on this approach, the tests presented in Section 2 can be used by different theoretical frameworks turning to layered representations reflecting the Asp(I) – Asp(II) distinction.