Introduction

This study was inspired by the plenary lecture by Zoltan Kövecses at the AFLiCo 9 conference in Lyon 3 in May 2024, where he presented the project of cross-cultural analysis of the metaphors of anger. He provided evidence for the existence of a conspicuous universal core value that can be traced across all corpora. On the other hand, the thesaurus of anger suggests that its shades, which are realized in synonyms and adjacent categories, offer a wide range of nationally specific variations. One of the specifically Ukrainian concepts is fury (Ukr. лють).

As part of a hybrid war (Bond, 2005; Hoffman, 2007), emotional response is one of the expected outcomes of ideological influence through propaganda (Hovland et al., 1953; Gustafsson and Hall, 2021; Wolak and Sokhey, 2022; Jamieson, 2023; Lakoff, 2016, 2024; Shah, 2024). In addition, the ongoing war in Ukraine, with its incessant stresses and challenges, has a strong impact on the psyche. Ukrainian society has to cope with an avalanche of first-hand and media information about the aggressor’s atrocities, deaths, deprivation, and massive destruction. This triggers emotional reactions such as stress, anxiety and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Lushchak et al., 2024), which include anger alongside the other five stages of grief (Kübler-Ross, 1969). Anger is capable of redirecting the outcome of a political event and is at the center of modern political science and linguistics research (Howard and Kollanyi, 2016; Benkler Faris and Roberts, 2018). The central role of anger as a key player in politics served as an impetus for the design of the outrage model in the media. It draws on recent social case studies that assert the growth of social media-fueled outrage and its manipulative potential as a result (Brader, 2005; Berry and Sobieraj, 2014; Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen, 2000).

On the other hand, in modern war-torn Ukraine, observers tend to argue that instead of destructive dynamics in the collective psyche, anger transforms into a nation-building factor, albeit in a lightly biased form, as fury (лють). It seems to be no coincidence that this word has become a hashtag on social media. The Ukrainian war story already knows a Telegram chat ЛЮТЬ (t.me/angryangrier), a documentary book Fury (Стеблівський, 2023), a song Ukrainian Fury (Українська лють) as a cover version of an Italian song Bella Ciao (Соловій, 2022), The Police Big Band of Ukraine with their music reel Untamed Fury (Нескорена лють, 2023), a documentary film Mariupol. The Fury Lets Me Breathe (Маріуполь. Лють дозволяє мені дихати 2023), a series of photos and painting exhibitions, e.g. a photo exhibition in Dnipro in 2023 (Любов/Лють 2023), the United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury (ОШБ НПУ «Лють») and the group Kozak System with their song Fury (Kozak System, 2023) as the anthem of this military division; and finally, various weapons, including a land drone Furious («Лютий») or an armoured robot of two generations Fury 1.0 and 2.0 (Дистанційно керований… 2024), all these names going back to the concept of the (Ukrainian) fury. This is proof of the central role of this concept in the national construal of the world and the Ukrainian worldview as its foundation. An example of this is the following passage, which refers to the strategic success of the Ukrainian army in liberating its territories in autumn 2022:

Українське диво 2022-го року створено не руками генералів та політиків – це сотні тисяч кращих людей на світі в одному пориві прощались з життям і йшли на війну, щоб продати своє життя подорожче, і саме ця відчайдушна народна лють [Hereinafter the translation is mine. I underline.] розгромила кадрову російську армію (Хвиля Десни, 7 лютого, 2024).

The Ukrainian miracle of 2022 wasn’t crafted by generals or politicians, but by hundreds of thousands of the world's finest people. These brave individuals, all at once, bid farewell to their lives and took up arms, determined to make their sacrifices count. It was this fury, this collective resolve that overcame the ranks of the Russian army [hereinafter the translation is mine and I underline].

Moreover, fury is widely used in poetic contexts, which further enhances its metaphorical potential. It is repeatedly compared to love, for example in the poetry collection by Maryna Ponomarenko (Пономаренко, 2023). In Ukrainian, love and fury have the same first syllable. As stated in the fragment of the commentary on the exhibition “LOVE/FURY” by Ukrainian photo artist Olga Fedorova:

Тоді як лють допомагає тобі боротися — любов допомагає тобі жити й насолоджуватись життям. Проходити крізь усі битви і не втрачати себе, не занурюватись в свою лють занадто глибоко та не ставати бездушними, нездатними бачити красу довкола. Лють — то є меч, а любов — то броня. Але любов також може стати мечем — проти тих, хто не має любові, або ж просто боїться любити. В такому разі лють стає бронею. І мені здається, аби виграти всі свої війни — нам потрібні вони обидві. Меч та броня. Любов та лють. (Артсвіт 2024).

While fury gives you the strength to fight, love gives you the reason to live and savor life. To face all the battles without losing yourself, without being consumed by fury and turning soulless, blind to the beauty around you—that's the true challenge. Fury is the sword, and love is the armor. But love can also become a sword against those who lack it, or fear it. In such cases, fury becomes the armor. It seems to me that to win all our wars, we need both: the sword and the armor. Love and fury.

Since fury occurs in both visual and verbal forms, the study of this concept aims to investigate the semiotic and cognitive mechanisms of its implementation as a nation-building concept actualized in (1) multimodal (memetic) images and (2) a lexical unit лють in the corpus of Ukrainian language media during the period of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 to the present. The two main aims of the study are therefore the following: (1) to reveal the semiotic and cognitive nature of the multimodal concept fury in the Ukrainian media sphere, with the task of showing the concept fury as a semiotic and cognitive nation-building entity in its visual and verbal realization, and (2) to model the lexical concept fury as a semiotic and cognitive structure implemented in the Ukrainian lexical unit лють, with the research task of reconstructing its scope through a semiotic and conceptual analysis.

1. Corpora and methods

1.1. Corpora

As a multimodal concept, fury is presented in the corpus of about 30 images named ЛЮТЬ. They were randomly selected from the set generated by the Google Image search engine. These images include paintings named ЛЮТЬ by their authors, various mobilization posters of the United Ukrainian Police Brigade Fury, merchandising items with the same logo, and random images as cover pages for Ukrainian songs with the name Fury on Deezer, YouTube, etc. Significantly, the same image can be reproduced under a different name and in different contexts. On the other hand, each of the images represents a unique associative cognitive complex linking the concept of fury with other national concepts within the Ukrainian information sphere. This corpus of images is the subject of the first research task, which is to analyze the semiotic potential of the multimodal concept fury in the Ukrainian media context.

In addition, the lexical means of the Ukrainian language, i.e. the actual name of the concept fury (лють), is the focus of the second objective of the study. It is a dataset created by me using the AI application Sketch Engine (https://www.sketchengine.eu/). This dataset was selected on the basis of the Ukrainian Trends, a daily updated monitor corpus of Ukrainian media, which grows by about 1 million words per day. It contains news articles, Wikipedia and other sources updated via RSS feeds (news) and parsed regularly to avoid repetition of texts within a month. The Ukrainian Trends corpus spans from the beginning of Russia’s invasion in February 2022 to the present day. The dataset used in this study originally amounted to 5,560 units лють and its lemmas as basically nouns. In further analysis, I included the adjectives symbolizing Ukrainian resistance in the war, e.g. Angry Birds (“Люті Пташки”), a name for Ukrainian drones. At the same time, I had to analyze the concordances to avoid topics that appear in the Ukrainian media but are not directly related to the war in Ukraine (e.g. international events, beau monde scandals, weather reports, and sports). The result is 4,680 units used in connection with the current war in Ukraine, both in the country and abroad.

1.2. Methods

The study draws on a number of state-of-the-art and classical theories.

First, the context of the study itself entails that its main unit, the concept fury, is considered part of CDA within the framework of political discourse analysis (Fairclough, 1989, 1995, 2003, 2006; van Dijk, 1993, 1998, 2008, 2009; Wodak, 1989). In shaping the cumulative effect of political discourse, the role of emotions can hardly be overestimated (Wodak, 2015). As mentioned in the introduction, emotions such as anger have always been at the heart of CDA. Emotions as game changers in political discourse are considered ideologems (Jameson, 1982; Lylo, 2017; Pinich, 2019). Among the numerous definitions, I will depart from Fredric Jameson’s “amphibious formation, whose essential structural feature can be described as its ability to manifest […] as a pseudoidea – a conceptual or belief system, an abstract value…” (1982: 170). This definition is consistent with the nature of the concept of fury, which is (i) considered as a nation-building concept that (ii) has a multimodal (amphibious) realization. In this study, therefore, the concept is considered in various realizations as a multimodal and lexical concept.

One of the hypotheses of the study is the assumption that the concept fury is currently one of the nation-building concepts in the Ukrainian construal of the world. Arguably, the status of a nation-building concept has at least three prerequisites: 1) the concept should recur multimodally; 2) it should cognitively underpin a socially significant word or phrase in the media (hashtag), and 3) it should be related to other nation-building concepts of the construal.

With regard to the first requirement for a nation-building concept, the semiotic and cognitive theories are used in combination, as claimed by cognitive semiotics in relation to meaning-making (Forceville, 2006, 2013, 2016; Zlatev, 2012). In this study, the cognitive semiotic potential of the concept fury is realized both multimodally and lexically.

The second prerequisite for a nation-building concept is its semiotic and cognitive analysis as a lexical unit.

The multimodal representation of the concept fury is analyzed through the lens of semiotic theory informed by cognitive science, particularly its framework of mental operations, or construal (Croft and Cruse, 2004: 46). This study employs classical Peircean semiotics, which classifies signs based on the interpreter’s perception of the relationship between a sign and its referent. Recognizing that the sign is only partially identical with the reality it presents, Peirce introduced the concept of modality. “Modality refers to the reality status accorded to or claimed by a sign, message, text, or genre” (Chandler, 2017: 80). Simply put, the greater the resemblance between a sign and its referent, the higher its modality. Accordingly, Peirce identified three primary types of signs, arranged in increasing order of modality: symbols, indices, and icons.

An icon is defined as a sign that “stands for something merely because it resembles an icon” (Peirce, 1935: 362). Although this definition may appear vague, this feature of an icon accounts for a very high modality of this type of sign. In essence, an icon closely mirrors the object it represents. However, when dealing with abstract concept such as fury, creating a visual iconic representation presents significant challenges. This is because a direct ‘portrait’ of fury is nearly inconceivable, necessitating a clear distinction between a vehicle of fury (its representation) and fury itself.

In this study, the iconic signs of fury are analyzed in two modes. The first mode involves the representation of fury through culturally significant personalities who serve as carriers of fury. Their fury may be depicted either symbolically or metaphorically, resulting in semiotic hybrids termed symbolic iconicity. This hybrid combines the qualities of an icon (the carrier of fury) with those of a symbol (fury itself). Based on modality of the carrier, these representations are categorized as either:

- symbolic icons, where specific, culturally significant personality is directly portrayed or

- iconic symbols, where the carriers function as abstract symbols within a cultural context.

These distinctions will be elaborated upon in the analysis.

The second mode of iconic representation involves lexigraphic images, where the name of the concept is directly rendered as the word лють. In the verbal concordances, such icons appear as the explicit linguistic labels for the emotion of fury.

Following Peirce, an index is “a sign which refers to the object that it denotes by virtue of being really affected by that object” (1936: 248). Indices, unlike icons, do not closely cite but instead maintain a physical and/or incidental connection to it, resulting in medium modality. This connection closely aligns with metonymy, where a phenomenon is described by emphasizing specific facets or domains within a domain matrix (Croft and Cruse, 2004: 47). This mental operation has a psychological basis. Similar to anger (Kövecses, 2000: 168), fury is associated with various physical indicators – such as facial expressions or skin tone – that can function as indices. Numerous verbal concordances also contain such metonymic indices of fury.

Symbols, in contrast, exhibit the lowest modality, as their meaning is determined conventionally and heavily reliant on cultural traditions and contexts. Unlike icons, which resemble their referents, or indices, which maintain a direct connection to them, symbols depend on interpretive habits or societal conventions. Cognitively, symbols share significant similarities with metaphors and other comparative mental operations that involve mappings between at least two domains: the source and the target (Croft and Cruse, 2004: 55).

The cognitive analysis of the concept fury draws on several cognitive theories. The first concerns the lexical concept in the sense of Vyvyan Evans’ Theory of Lexical Concepts and Cognitive Models (LCCM). It states that a concept serves as the basis for its realization in lexical units, which in turn serve as triggers for the conceptual domains (a). The second cognitive theory is based on Zoltán Kövecses’ research on the concept anger (1986, 1995b, 2000, 2024). In this study, his cognitive modeling is first conducted as metaphorical mapping to determine the scope of the metaphor (Kövecses, 1995a, 2003). This mapping follows the classical procedure of modeling the interrelation of the elements between the target and source domains. In addition, operations of conceptual integration are also included, which are widely used in mapping visual metaphors in terms of the Theory of Extended Conceptual Metaphor and Metonymy (Kövecses, 2020, 2022). In this case, instead of two domains, the model comprises four mental spaces (see e.g. Fauconnier and Turner, 2003: 59), with the blended space serving the cognitive underpinning of the lexical unit. Second, the unit лють verbalizes a metonymy that implements fury as a physiological phenomenon within the same domain (Croft and Cruse, 2004: 216). The investigation of the lexical concept fury is thus a corpus-based analysis of the dataset. The annotation procedure is conditioned by the fact that the lexical unit can be used in the war-related context as a sign (an icon or a symbol) or as a cognitive construal of a metaphor or metonymy. Significantly, an index and a metonymy have similar characteristics. This explains the lack of semiotic annotation of the units as indices.

The explanation of the nature of the concept fury as a nation-building concept refers the study to the third classical cognitive theory. It states that there is a system of interconnected nationally significant concepts underpinned by values (Sharifian, 2017) as a national construal of the world (Taylor and MacLaury, 1995), a dynamic conceptual structure based on national values (Musolff, 2021). The third premise of a nation-building concept will allow reconstructing its references to other Ukrainian national concepts of the construal of the world. This will clarify its place in the conceptual hierarchy and its potential to maintain the sustainable cognitive basis for the secure information space of the country facing the challenges of war.

2. Semiotic and cognitive potential of the multimodal concept fury

Having emerged from the earliest days of the war, the notion of fury is ubiquitous in the Ukrainian informational space. It can clearly be traced back to the beginning of the military conflict in Donbas when tragic events elicited appropriate traumatic responses. However, the real boom in the use of fury occurred with Russia’s the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

2.1. Multimodal concept fury as an iconic sign

From a semiotic perspective, given its abstract nature, fury might not seem easily depicted as a form. However, some Ukrainian artists claim to have portrayed the essence of fury in their artworks. These include paintings titled Fury or works that feature elements which allegedly represent fury in iconic terms. Symbolic iconicity, described in 1.2, the first type of signs, symbolic icons, will be analyzed here. It means that the carriers of fury are culturally significant personalities, who demonstrate fury as their inherent feature.

One prominent example of such an iconic portrayal is Mavka in Fury (Figure 1), an animated character from Mavka. The Forest Song (Мавка. Лісова пісня, 2022), based on one of the most famous works of Lesia Ukrainka, a classic of Ukrainian literature. The film is considered significant not only for its adaptation of a Ukrainian literary gem, but also for its strong, nationally specific Ukrainian focus. Mavka, a spirit and guardian goddess of the Forest that embodies natural beauty, love and courage. She frequently expresses strong emotions, one of which is her fury, a state depicted in Figure 1. It is not by accident that, in addition to its iconic form, the portrayal also uses metaphoric connections, linking Mavka’s fury to a forest fire. Her hair resembles sparkles and flames, while her eyes and aura radiate the white and red heat of fury. Another series of iconic images is found in the Ukrainian calendar Лють for 2024 (Figure 2), which features photo portraits of 12 Ukrainian military servicemen. According to its creators, the patriotic Fund 1991, the calendar is a continuation of a photo project aimed at reminding the world that the war has now lasted for 10 years. These symbolic icons represent the 12 months of invincibility and courage of 2024 (Календар ЛЮТЬ, 2023). Thus, the semiotic functions of these symbolic icons merge their iconic and symbolic qualities, and combined with metaphoric representation of fury, embody the concepts of invincibility and courage.

Figure 1 (left) and Figure 2 (right)

Figure 1: Iconic image (symbolic icon) of fury implemented as Mavka’s emotion (Film.UA Group).

Figure 2: Iconic image (symbolic icon) of fury as a Fund 1991 calendar of 2024 (created by Vitaly Yurasov).

Another type of iconic images of fury appears in nationally-themed merchandise aimed at youth, such as T-shirts and baseball caps (Figure 3). These feature lexigraphic elements that not only iconically depict the word лють but also evoke metaphoric associations through indexical references: bloody scratches resembling animal claws, the rough, slipshod font, and the use of red coloring.

Figure 3

Iconic image of fury as a lexigraphic element in the Ukrainian national merchandise (designed by Maxim Moshkovsky).

In summary, iconically, fury serves to represent key nation-building concepts such as natural beauty, love, courage, and invincibility. These concepts are expressed through of nationally significant figures, both real and fictional, as well as through lexigraphic images with indexical elements.

2.2. Multimodal concept fury as an indexical sign

The indexical nature of the fury is exemplified in the following memetic images titled Лють:

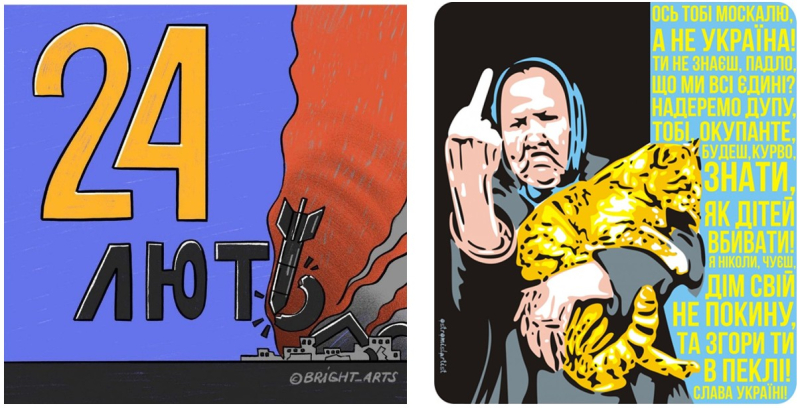

Figure 4 (left) and Figure 5 (right)

Figure 4: Indexical image of fury as a date of the fill-scale invasion (drawing by Yaroslava Yatsuba, known as @bright_arts on Instagram).

Figure 5: Indexical image of fury as a recapped meme ‘The Granny and her Cat’ (‘Baba i Kiт’), from a drawing by Serhii Bryliov (ostromislartist).

In Figure 4, the similarity in the orthography of the Ukrainian name for February, лютий (lit. furious) and the word лють serves as the derivative stem. The image splits reality, presenting a once-peaceful scene in Ukrainian yellow and blue on the left and red and black of war on the right. A bomb strikes the letter O in the name of the month, shattering the remaining letters and transforming it into лють. This visual metaphor represents the emotional response of Ukrainians, which will forever be linked to the onset of the full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. In Figure 5, a popular Ukrainian memetic character – a granny and her cat – indicates to the Ukrainian people confronting aggression. Her indexical gesture conveys both defiance and hatred towards the enemy. The accompanying rhyme directly addresses the aggressor:

Here what you’ll get, moskal [derogative slang for a Russian], but Ukraine. Don’t you know, mother f@cker, that we are all united? [This line underscores the theme of unity]. We will burn your ass, you occupant. You will know, kurwa, how to kill children. Never will I abandon my home, do you hear? [resilience and invincibility]. Burn in hell. Glory to Ukraine!

This meme not only communicates fury through the grandmother’s indexical gesture, but also through the symbolic use of yellow and blue coloring in the text.

Thus, indexically, fury represents Ukrainians’ emotional response to aggression, intertwined with concepts such as defiance, hatred towards the enemy, unity, resilience and invincibility.

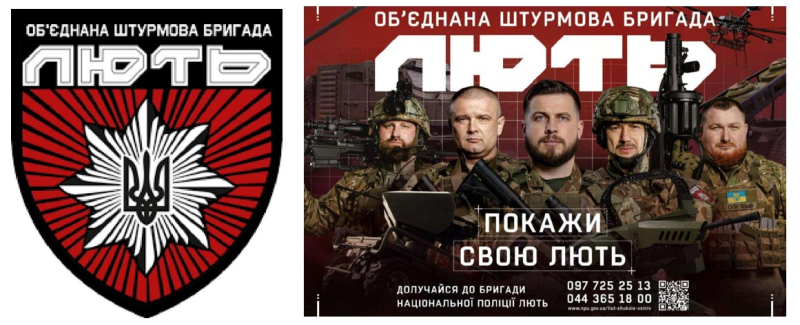

2.3. Multimodal concept fury as a symbolic sign

Symbolically, fury is most commonly represented in military insignia and in the mobilization poster of the United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury (Figures 6 and 7). The symbolism here combines with iconicity, as the representation of the human emotion fury is reinforced by the lexigraphic element, the word лють.

Figure 6 (left) and Figure 7 (right)

Figure 6: Symbolic image of fury as a military uniform chevron of the United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury.

Figure 7 (right): Symbolic image of fury as a mobilization poster of the United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury.

The poster in Figure 7 also features the logo Demonstrate your fury, anchoring the images as iconic elements that depict the brigade’s officers. These servicemen exemplify courage and invincibility, supporting core national values.

The second category of iconic hybrids associated with fury, termed iconic symbols, encompasses representations of Ukraine as a woman-warrior (Figures 8 and 9). Unlike symbolic icons, this category emphasizes the abstract, nationally significant nature of the fury carrier, depicted here as a woman. The low modality of such representations fosters a stable cultural association among insiders, linking Ukraine with a feminine identity. This association is further reinforced by the linguistic personification of Ukraine as female, derived from the grammatical feminine gender of the country’s name in the Ukrainian language. Additionally, one of Ukraine’s symbols of invincibility and guarding is Berehynia, the Guardian Goddess of home and family (http://ukrlit.org/slovnyk/).

Figure 8 (left) and Figure 9 (right)

Figure 8: Symbolic image (iconic symbol) of fury as a Ukrainian woman-warrior.

Figure 9: Symbolic image (iconic symbol) of fury as a Ukrainian woman-warrior (street art work of Kostantin Kachanovsky).

Both images highlight uniquely Ukrainian symbols, such as the national costume: a wreath symbolizing victory, beauty and honesty (Український вінок), an embroidered shirt (вишиванка), whose patterns and colors hold encrypted meanings, and a special necklace (гердан) resembling guelder rose berries (калина), a national symbol of Ukraine (Kotsur, Potapenko, Kuybida, 2002: 12). The guelder rose is also referenced in the song The Red Guelder Rose, the anthem of Ukrainian resistance. Additionally, the woman-warrior is depicted with modern military gear, standing for invincibility. These symbolic images, therefore, convey nation-building concepts like victory, beauty, honesty, resistance, guarding, cultural uniqueness, and invincibility.

Another set of symbolic images of fury is found in memetic representations specific to Ukrainian culture or universal symbols. In Figure 10, a hunter wields a pitchfork – historically a weapon of Ukrainian peasants during uprisings against Russian tyranny – against a bear, the totem of Russia. Ukrainian national symbols reinforce the message. Oseledets’ (оселедець), Kozak’s distinctive haircut, suggests Ukrainian Kozak spirit associated with their love of liberty (liberty), and the pitchfork’s shape mirroring the Trident (Тризуб), a symbol of Ukraine, suggests the concept of sovereignity. The yellow-and-blue background highlights the liberation struggle for the motherland. Thus, these symbols convey concepts such as Ukrainian Kozak spirit (liberty), motherland and sovereignity. In Figure 11, a military uniform chevron combines a symbol of death with Ukrainian heraldic colors and the Trident. This chevron is also associated with the informal Ukrainian slogan Glory to the nation, Death to the enemies! (Слава нації, смерть ворогам!). Therefore, these symbols represent concepts such as the Ukrainian Kozak spirit (liberty), motherland, sovereignty and death to the enemy.

Figure 10 (left) and Figure 11 (right)

Figure 10: Symbolic image of fury as a meme.

Figure 11: Symbolic image of fury as a Ukrainian military uniform chevron.

Finally, fury is symbolically represented in Ukrainian merchandise. For example, a warm scarf (Утеплена хустка…) features a symbolic pattern (Figure 12).

Figure 12

Symbolic image of fury as a specifically patterned warm scarf (from Ukrainian brand Nesamovýto).

Its pattern is expounded in the comment on the designer’s site the following way:

The “Fury” scarf is a silk talisman, featuring yellow buttercup flowers blooming against a deep green background. At the heart of the design lies the key word of the collection: Fury. Our Fury Grows. It cannot be stopped—but only it can halt, halt the enemy forever.

The buttercup has been chosen deliberately. This vibrant flower, though seemingly delicate, possesses a dual nature: on one hand, it offers remarkable healing properties, while on the other, it is toxic to animals. A flower that knows how to defend itself, despite its fragile appearance.

As the text demonstrates, its pattern is conditioned by a symbolism of the phytonym жовтець (Ukr. for buttercup). Significantly, in Russian, its name, лютик, shares the root with the Ukrainian лють, connecting it to the fury collection of merchandise. This design reflects the dual nature of the buttercup, symbolizing both fragility and invincibility, qualities attributed to the Ukrainian people.

As an interim conclusion, semiotically, the multimodal concept fury is expressed through all three basic types of signs: icon, index, and symbol also featuring their hybrids in terms of iconic symbolism. As an icon, fury is featured in portraits of nationally significant figures, both real and fictional as symbolic icons or iconic symbols, as well as in lexigraphic images. Indexically, fury is referenced visually or lexigraphically through historical events or prototypical figures, using specific gestures. Symbolically, fury is closely linked to Ukrainian heraldic signs. Conceptually, fury is associated with nation-building concepts such as natural beauty, love, fragile, victory, honesty, courage, invincibility, defiance, hatred/death to the enemy, unity, resilience, Ukrainian Kozak spirit (liberty), motherland, and sovereignty.

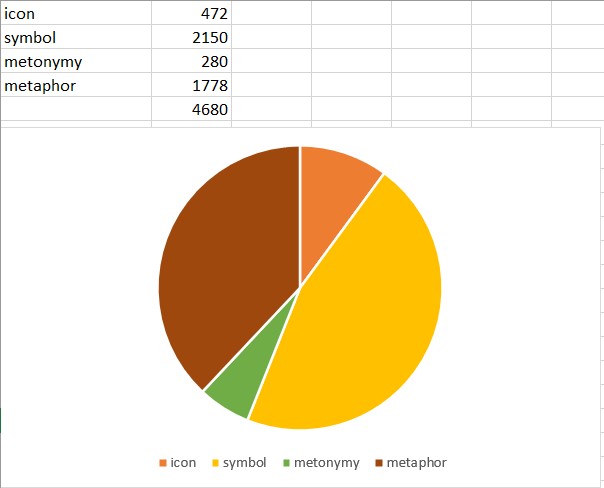

3. Semiotic and cognitive potential of the lexical concept fury

The dataset of the lexical unit лють was manually annotated to determine the semiotic significance of the concept FURY and to identify instances where the concept in construed as metaphor or metonymy. The annotation process aimed to classify the type of sign the unit represents (icon or symbol) and the mental operation it verbalizes (metaphor or metonymy). As previously mentioned, the cognitive similarity between index and metonymy explains why index was not included as an annotation tag. The concordance results revealed the following proportion of semantically vs. cognitively significant implementations of the Ukrainian concept лють (Figure 13):

Figure 13: The proportion of semiotically and cognitively significant implementations of the Ukrainian lexical concept fury

3.1. Lexical concept fury as an iconic sign

The concept fury is presented iconically when the lexical unit directly names the emotion, i.e., when it is explicitly referred to as лють. A typical example of this occurs in the following context:

| 24tv.ua | номерами в братській могилі в Мангуші. </s><s> Якщо є в 21 сторіччі більший воєнний злочин проти людства, то я не знаю, який. </s><s> | icon | Лють | . </s><s> Просто лють", – наголошував Петро Андрющенко. </s><s> Відповідальним за облогу та руйнування Маріуполя вважають |

| 24tv.ua | the numbers in the collective tomb are the numbers in the mass grave in Mangush. </s><s> If there is a greater war crime against humanity in the 21st century, I don't know what it is. </s><s> | icon | Fury | . </s><s> Just fury,’ Petro Andriushchenko emphasised. </s><s> The following are considered responsible for the siege and destruction of Mariupol |

This example shows that fury is explicitly mentioned as the emotional response of Ukrainians to the events in Mariupol during its siege by the Russian Army in the spring of 2022. Notably, the concept is expressed as an independent phrase, shaped as an elliptical sentence.

It is worth noting, however, that even in cases of direct reference to an emotional response, the lexical unit, when functioning as an iconic sign, may exhibit a tendency toward contextual metaphorization or symbolization. Consider the following example:

| gk-press.if.ua | пам’ять в крові кожного з нас, а окрім неї незламна Віра, Воля до життя, яке ми самі собі обираємо, та Свобода. </s><s> А ще | icon | Лють | за кожне загублене безневинне життя, зламані долі, жахливі звірства. </s><s> Ми показали усьому світу, ким насправді є |

| gk-press.if.ua | memory in the blood of each of us, and besides it, unbreakable Faith, the Will to live the life we choose for ourselves, and Freedom. </s><s> And also | icon | Fury | for every innocent life lost, fate broken, horrific atrocities. </s><s> We showed the whole world who they really are |

In this case, the direct use of the lexical unit is accompanied by the antonomasia of other concepts, such as faith, will and freedom, which imbues the term with symbolic significance. Referring to fury as something that exists “in the blood”, alongside historical memory, further demonstrates its metaphorical use.

These examples underscore that semiotic units have a strong cognitive foundation, as the construal of meaning often reflects the overlap between symbols and metaphors (Forceville, 2013).

3.2. Lexical concept fury as a symbolic sign

The symbolic value of the lexical concept fury is evident when the unit is used to name specific physical entities, such as a military division, drone, or robot.

The name of The United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury accounts for the largest proportion of symbolic uses in the concordance, as the actions and personnel of this brigade frequently receive media attention, as seen in the following example:

| loga.gov.ua | до лав «Гвардії наступу». </s><s> Як організовано рекрутинг бійців окремої штурмової бригади Національної поліції « | symbol | Лють | » з числа жителів Луганщини побачили журналісти луганських медіа. </s><s> Вони відвідали Правобережний та Лівобережний |

| loga.gov.ua | to the ranks of the ‘Offensive Guard’. </s><s> Journalists from the Luhansk region saw how the recruitment of fighters of the separate assault brigade of the National Police ‘ | symbol | Fury | ’ from among the residents of Luhansk region is organized. </s><s> They visited the Right Bank and Left Bank |

In this instance, the unit Лють is used as the name of a military division, demonstrating its symbolic significance. Orthographically, it appears as a proper name in quotation marks.

The same orthographic treatment is observed in the naming of the patriotic hit song:

| tvoemisto.tv | », «Хто як не ти» й хіти воєнного часу «Українська лють», «Я твоя зброя» та інші. 24 листопада зустрічайте «Українську | symbol | лють | » Христини Соловій у Львові. </s><s> |

| tvoemisto.tv | ’, ‘Who else but you’ and wartime hits ‘Ukrainian Fury’, ‘I am your weapon’ and others. On 24 November, meet ‘Ukrainian | symbol | Fury | ’ by Khrystyna Soloviy in Lviv. </s><s |

This example refers to the wartime song Ukrainian Fury, a remastering of the Italian resistance song Bella Ciao.

The same concerns the names of arms, drones and robots, as in the following:

| rbc.ua | </s><s> Є броня та танковий кулемет. </s><s> В Україні розпочалися тести бойового робота " | symbol | Лють | " </s><s> Він може застосовуватися для штурму чи оборони позицій. </s> |

| rbc.ua | </s><s> It has armour and a tank machine gun. </s><s> In Ukraine, tests of the combat robot ‘ | symbol | Fury | ‘ </s><s> have begun </s><s> It can be used for assault or defense of positions. </s> |

Here again, the unit retains the same orthographic treatment as other symbolic uses of the concept fury.

Thus, semiotically, the Ukrainian lexical concept fury exhibits strong potential both as a symbol and an icon. As an icon, it is used in its direct meaning to name an appropriate emotion. As a symbol, it serves as the name of military divisions, weapons, and other significant entities. The indexical potential of this concept is revealed in its metonymic implementation.

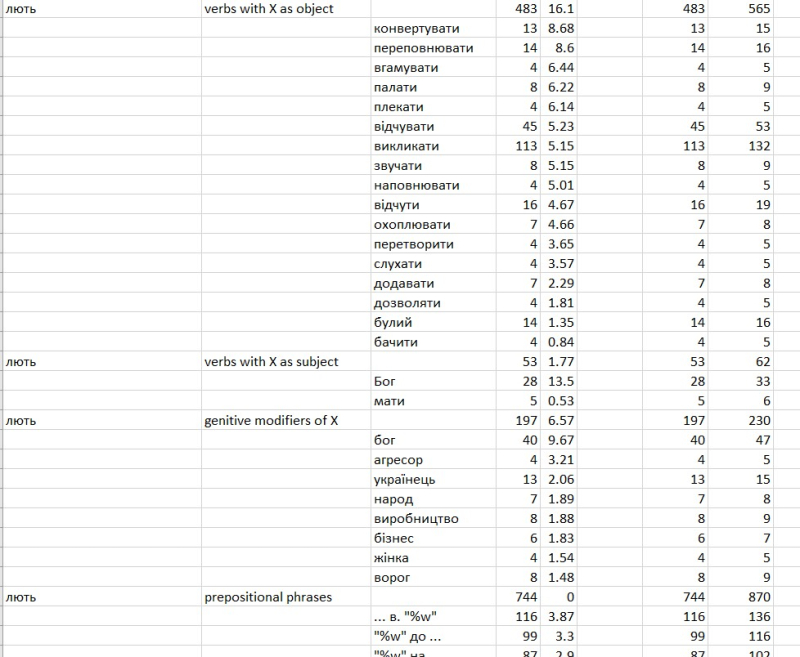

3.3. Ukrainian lexical concept fury as a metonymic construal

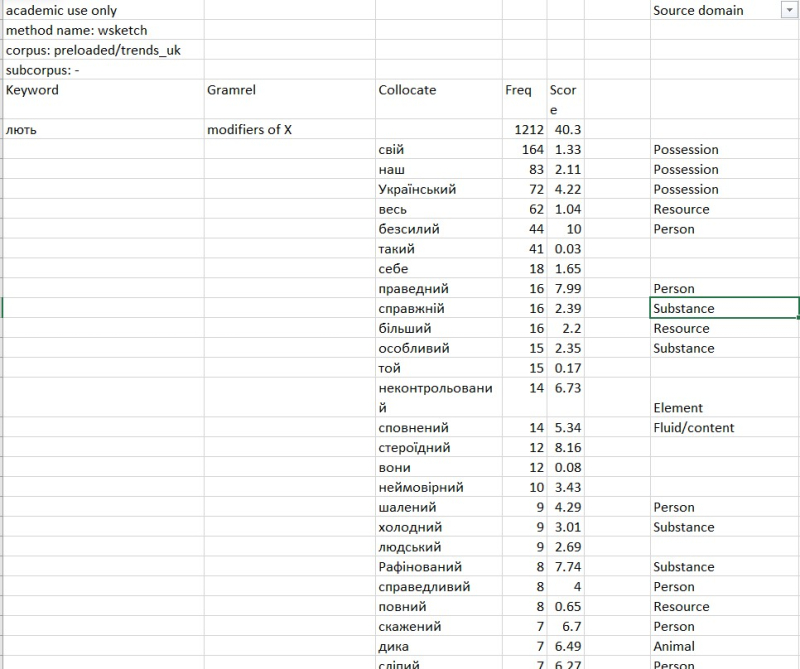

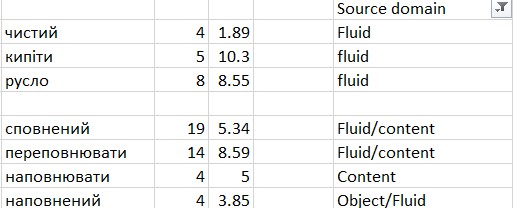

The Ukrainian lexical concept fury is implemented metonymically through various collocations, as revealed by the Word Sketch application in Sketch Engine. This tool allowed for the identification of typical collocations, which were then automatically categorized based on grammatical structure. A fragment of the resulting chart is shown in Figure 14:

Figure 14: A fragment of the Word Sketch Chart of the most frequent collocations of the Ukrainian lexical concept fury verbalized in the unit лють

Metonymically, the concept fury refers to observable signs of its presence in people.

First, fury is frequently mentioned as a booster or tool that enables certain actions or drives specific behavioral patterns. Verbally, this is often expressed in collocations using the preposition with (із/з). These collocations occur with relatively high frequency. For example:

| 10ukraine.com.ua | , почав відходити в оборону та намагатися вразити в контратаках. </s><s> Почалася вже рівна битва. </s><s> З енергією, швидкістю та | metonymy | люттю | , але без небезпечних моментів. </s><s> |

| 10ukraine.com.ua | , began to retreat to the defense and try to strike in counterattacks. </s><s> An equal battle has already begun. </With energy, speed and | metonymy | fury | , but without dangerous moments. </s><s></s><s>. |

In this instance, fury is described as an accompanying emotion that amplifies the enemy’s actions.

It is important to note that while the multimodal concept fury typically characterizes the emotional state of Ukrainians, which is the focus of this research, the lexical concept can apply to both sides of the conflict.

It is evident in the following prominent group of collocations that involves descriptions of how fury manifests physiologically.

The most frequent representation of лють is its association with an extreme mental state, such as insanity ascribed to the enemy:

| unian.ua | </s><s> "Не тямив себе від | metonymy | люті | ": розкрито деталі останньої відомої зустрічі Пригожина з Путіним </s><s> Перед аудієнцією ватажок "Вагнера" перебував у |

| unian.ua | </s><s> ‘I was beside myself with | metonymy | fury | ’: details of Prigozhin's last known meeting with Putin revealed </s><s> Before the audience, the Wagner leader was in |

In this example, the head of the Wagner Russian Division, Yevgeny Prigozhin, is portrayed as being in a state of insanity induced by fury.

| glavcom.ua | розтоптали міф про «другу армію світу» і принизили «непереможну росію»…</s><s> Ворог це бачить, казиться від безсилої | metonymy | люті | , кидає сотні тисяч свого «гарматного м’яса» на українські бастіони… і добряче отримує по своїх, кривих і дірявих, |

| glavcom.ua | trampled on the myth of the ‘second army of the world’ and humiliated the ‘invincible Russia’…</s><s> The enemy sees this, goes crazy with impotent | metonymy | fury | , throws hundreds of thousands of its ‘cannon fodder’ at Ukrainian bastions… and gets a good hit on its own, crooked and leaky, |

Other psychological signs of fury include trembling and body shaking, as seen in the following example:

| espreso.tv | реагуватиме по-своєму. </s><s> Викидатиме кортизол, адреналін і все, що воно там викидає, щоби нас починало трусити від | metonymy | люті | . </s |

| espreso.tv | will react in its own way. </s><s> It will release cortisol, adrenaline, and whatever else it releases to make us shake with | metonymy | fury | . </s |

Another physiological response, teeth grinding, is exemplified as follows:

| tverezo.info | передача допомоги та ще й не на фронті – це от “не цікава історія та не його масштаб”. </s><s> Знаєте, в мене аж зуби зарипіли від | metonymy | люті | ! </s><s> Не цікава історія?! </s><s> Допомога курсантам військового вишу не його формат?! </s><s> Ці юнаки та дівчата у 2024 році прийшли |

| tverezo.info | The transfer of aid, and not even at the frontline, is ‘not an interesting story and not his format’. </‘You know, my teeth were grinding from the | metonymy | fury | !’ <s><s> Not an interesting story?! </s><s> Helping cadets of a military university is not his format?! |

A further physical reaction, fists clenching, is shown in this example:

| volynpost.com | <s> «Загинули люди, палають мирні багатоповерхівки. </s><s> Знову стискаються від | metonymy | люті | та ненависті кулаки. </s> |

| volynpost.com | <s> ‘People died, peaceful high-rise buildings are burning. </s><s> Fists are clenching again from | metonymy | fury | and hatred. </s> |

Additionally, crying out loud, as a social response to fury, is demonstrated in this context:

| gazeta-misto.te.ua | та істота, для якої є тільки одне визначення – нелюдь! </s><s> Мабуть більшість українців, здригаючись від жаху та волаючи від | metonymy | люті | від того, що творять нелюді з росії, жалкують про те, що з молоком матері ввібрали в себе людяність. </s><s> Що, навіть воюючи з |

| gazeta-misto.te.ua | The creature for which there is only one definition - non-human!"</s><s> Perhaps most Ukrainians, shuddering in horror and screaming with | metaphor | fury | at what the non-humans from Russia are doing, regret that they absorbed humanity with their mother's milk. </s><s> That, even when fighting against |

Finally, lacking words to fully express emotions stirred by fury is conveyed in this example:

| gazeta.ua | України. </s><s> Телефоную їм, щоб ішли з нами. </s><s> Погодився один. </s><s> Решта сказала, що нацизм треба подолати. </s><s> Не мав слів від | metonymy | люті | . </s> |

| gazeta.ua | Ukraine. </s><s> I call them to come with us. </One of them agreed. </The others said that Nazism must be overcome. </s><s> I was at a loss for words from | metonymy | fury | . </s> |

In summary, the metonymic expressions of the Ukrainian lexical concept fury in war-related media are rooted in a single conceptual domain. When verbalized through the lexical unit лють, it represents a booster or tool, an extreme mental state like insanity, and various physiological responses, physiological ways of its evidencing, such as body shaking, teeth grinding, and fists clenching. It also manifests in social reactions like crying out loud and lacking words.

3.4. Ukrainian lexical concept fury as a metaphoric construal

The metaphorical construal of the concept fury in the Ukrainian context reveals a wide range of source domains, many of which are commonly associated with figurative expressions of anger (Kövecses, 1986, 1995b, 2000). However, the specific proportion and contextual usage of the Ukrainian lexical unit лють in war-related discourse requires distinct consideration.

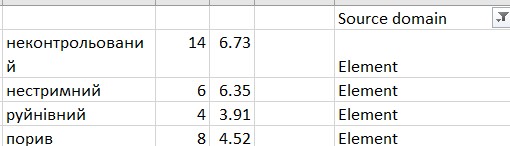

Through manual annotation of collocations that metaphorically verbalize fury, a typology of source domains was identified. The collocations were sorted according to the source domain they verbalize, resulting in the following chart (a fragment is shown in Figure 15):

Figure 15: A fragment of the Word Sketch Chart annotated according to the source domain of the metaphor of fury verbalized by the Ukrainian unit лють

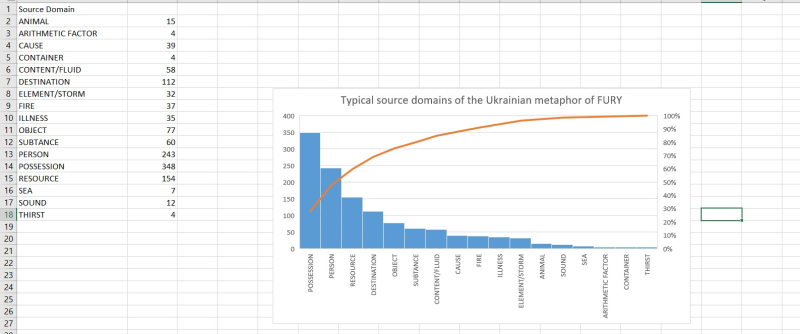

A quantitative comparison of these source domains is displayed in Figure 16:

Figure 16: Most frequently verbalized source domains of the Ukrainian metaphor of fury

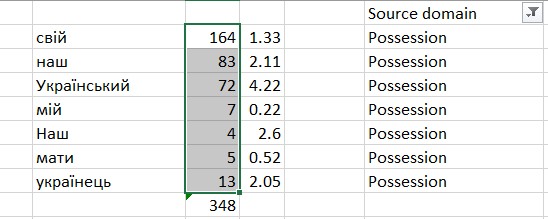

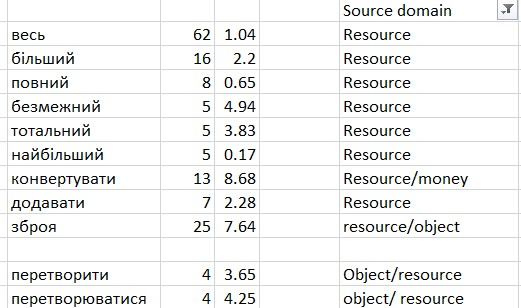

The most frequent source domain for fury is possession, which is realized in the following collocations (see Figure 17):

Figure 17: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain possession of the metaphor of fury

As an example from the dataset, the source domain possession is implemented as follows:

| espreso.tv | додає: "Приїжджаючи на фронт, я щоразу нагадую собі, для чого це все, заради чого наша боротьба і де коріння нашої | metaphor | люті | , яка дає нам сил битися і перемагати". </s> |

| espreso.tv | adds: ‘Coming to the front, I remind myself every time what it's all about, what our struggle is for, and where the roots of our | metaphor | fury | are, which gives us the strength to fight and win.’ </s> |

This example illustrates how the metaphor with possession as the source domain is combined with another metaphor derived from the plant domain. Such combinations are not uncommon.

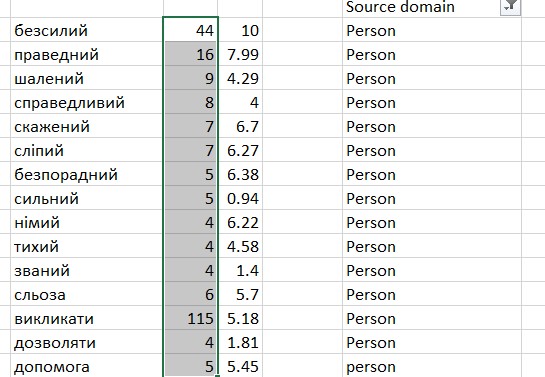

The second most frequent source domain is person, implemented in Ukrainian collocations like these (see Figure 18):

Figure 18: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain person of the metaphor of fury

For instance, it is lexically realized as follows:

| volynnews.com | <s> «кремль і російська банда! </s><s> Своїми обстрілами ви викликаєте в нас тільки | metaphor | лють | і презирство! </s><s> Не страх, не бажання про щось домовлятися. </s><s> Ви пробуджуєте в нас бажання нищити вас, терористів, де б ви не |

| volynnews.com | <s> ‘The Kremlin and the Russian gang! </s><s> With your shelling, you evoke in us only | metaphor | fury | and contempt! </s><s> Not fear, not a desire to negotiate. </You awaken in us the desire to destroy you, terrorists, wherever you are |

In this example, fury is metaphorically depicted as an animate creature that can be summoned or invoked.

The third most common source domain is resource, implemented in collocations such as these (see Figure 19):

Figure 19 : The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain resource of the metaphor of fury

A corpus example of this metaphor is:

| lviv-online.com | бомбосховищем у підвалі свого будинку в Харкові, художниця почала писати ці поезії. </s><s> В них Оля Федорова вклала усю свою | metaphor | лють | , увесь свій гнів до росіян, які кожного дня нищили рідне місто, країну – і продовжують це робити й зараз. </s><s> «На той час у |

| lviv-online.com | In a bomb shelter in the basement of her house in Kharkiv, the artist began to write these poems. </s><s> In them, Olya Fedorova put all her | metaphor | fury | , all her anger towards the Russians who were destroying her hometown and country every day - and continue to do so today. </s><s> ‘At that time, in |

Here, fury is framed as a resource that can be contributed, invested, or applied, akin to an asset or fund. One notable usage of this metaphor in the Ukrainian media is the slogan for a crowdfunding campaign supporting the Ukrainian army: Convert your fury into donations! The same metaphor is embedded in the hymn of the United Ukrainian Police Assault Brigade Fury (Kozak System…2023), reinforcing fury as a nation-building concept.

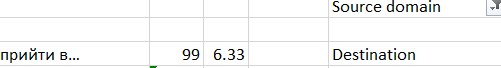

Another frequent source domain is destination, verbalized in collocations like these (see Figure 20):

Figure 20: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain destination of the metaphor of fury

In the corpus, it is verbalized the following way:

| 057.ua | співчуття у зв'язку з атакою ХАМАС. </s><s> Показова реакція на заяви путіна німецького лідера Олафа Шольца: "Я приходжу в | metaphor | лють | , коли чую, як російський президент направо і наліво роздає попередження про те, що жертвами військової конфронтації |

| 057.ua | condolences in connection with the Hamas attack. </s><s> German leader Olaf Scholz's reaction to Putin’s statements is illustrative: ‘I get into | metaphor | fury | , when I hear the Russian president issuing warnings right and left that the victims of the military confrontation |

In this example, fury is metaphorically presented as a final emotional state or endpoint that someone reaches.

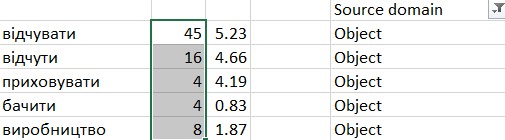

The next frequent source domain is object, implemented in collocations like these (see Figure 21):

Figure 21: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain object of the metaphor of fury

In this context, fury is conceptualized as a physical object that can be touched, felt, hidden, seen, or produced, as shown in the following example:

| vsim.ua | засоби та озброєння, там я здобув такий колосальний воєнний та життєвий досвід, відчув таку силу в собі й таку | metaphor | лють | проти ворога, що їх вистачить на все моє подальше життя, допоки жодного з тих нелюдів не залишиться на землі, - |

| vsim.ua | and weapons, there I gained such colossal military and life experience, felt such strength in myself and such | metaphor | fury | against the enemy that will last me for the rest of my life, until not a single one of those inhumans is left on earth, - |

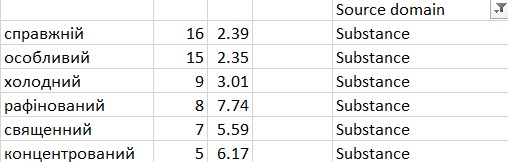

The substance source domain follows in frequency, represented in collocations such as these (see Figure 22):

Figure 22: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain substance of the metaphor of fury

This metaphor depicts fury as possessing various qualities, such as being authentic, special, cold, refined, sacred, and concentrated.

As an example:

| 7dniv.rv.ua | бійці із позивними «Воха», «Радіан» та «Ліон» захищають кордони нашої держави та демонструють справжню українську | metaphor | лють | у боротьбі з ворогом. </s><s> Крім того, один із них – «Ліон», евакуюючи загиблого бійця під час бойового виходу, отримав |

| 7dniv.rv.ua | The soldiers with the call signs ‘Vokha’, ‘Radian’ and ‘Lyon’ are defending the borders of our country and demonstrating true Ukrainian | metaphor | fury | in the fight against the enemy. </s><s> In addition, one of them, ‘Lyon’, while evacuating a fallen soldier during a combat mission, suffered |

Notably, fury is associated with an authentic emotional response inherent to Ukrainians, underscoring its significance in the national construal of the world.

The next source domain is contents or fluid, represented in collocations such as these (see Figure 23):

Figure 23: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain content/fluid of the metaphor of fury

Here, fury is depicted as a fluid that can fill, flood, overwhelm, or boil over. It can also be described as pure, having an estuary, or being capable of overflowing.

An example from the concordance is as follows:

| iz.com.ua | життя, сповнений мрій і планів. </s><s> Але ворог забирає кращих синів України. </s><s> Стискається серце, болить душа, переповнює | metaphor | лють | . </s> |

| iz.com.ua | a life full of dreams and plans. </s><s> But the enemy takes away the best sons of Ukraine. </s><s> My heart is tight, my soul hurts, I am overwhelmed with | metaphor | fury | . </s> |

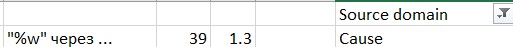

The cause domain is another source, implemented in collocations shown in the screenshot (see Figure 24):

Figure 24: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain cause of the metaphor of fury

In the concordance, it is featured in the following manner:

| dw.com | . І їм не вдалося. Вони на цьому інформаційному полі програли, і саме тому Путін фактично впав у цю істерію і просто від | metaphor | люті | , від бажання помститися і розпочав фактично цю війну. </s> |

| dw.com | . And they failed. They lost in this information field, and that's why Putin actually fell into this hysteria and simply out of | metaphor |

rage/ fury |

, out of a desire for revenge, he actually started this war. </s> |

This phrase is often translated as the collocation “out of rage”, though Ukrainian sources frequently translate лють as fury (for instance, as the name of a weapon) (Ukraine deploys…2024).

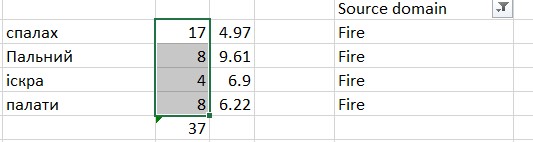

The next source domain, fire, is represented in collocations such as these (see Figure 25):

Figure 25: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain fire of the metaphor of fury

In this domain, fury is depicted as something that flashes, sparks, fuels, or burns.

In the concordance, this is verbalized as:

| korrespondent.net | цілеспрямовано били критично важливою для нормального життя інфраструктури. </s><s> Йдеться про одиничний спалах | metaphor | люті | через провали на фронті, чи нову тактику ворога? </s><s> Удари від безсилля </s> |

| korrespondent.net | targeted infrastructure critical to normal life. </s><s> Is this a single outbreak of | metaphor | fury | over the failures at the front, or a new tactic of the enemy? </s><s> |

In contrast to the English translation, where fury is described as an “outbreak”, in Ukrainian, it is portrayed as a “flash”.

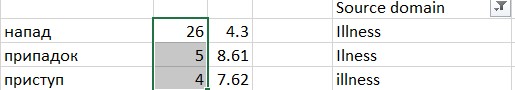

Another source domain, illness, is expressed in collocations like these (see Figure 26):

Figure 26: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain illness of the metaphor of fury

These collocations liken fury to an ailment, with symptoms like fits or bouts of emotional intensity.

The concordance provides the following example:

| wz.lviv.ua | немислиме з погляду колишніх уявлень про ядерне стримування – правлячі кола групи країн у нападі розпачливої | metaphor | люті | розв’язали повномасштабну війну на кордонах ядерної наддержави. </s><s> Страх ядерної ескалації слід відновлювати. </s> |

| wz.lviv.ua | unimaginable from the point of view of previous conceptions of nuclear deterrence - the ruling circles of a group of countries, in a fit of desperate | metaphor | fury | , unleashed a full-scale war on the borders of a nuclear superpower. </s><s> The fear of nuclear escalation needs to be restored. </s> |

Finally, the source domain element/storm is represented in collocations such as these (see Figure 27):

Figure 27: The list of Ukrainian collocations that verbalize the source domain element/storm of the metaphor of fury

Here, fury is described as an uncontrollable force, manifested in blasts, and portrayed as something uncontrollable and destructive.

In the concordance, this is illustrated as:

| korrespondent.net | місце". </s><s> "Раніше він дотримувався стриманості з підлеглими, тоді як зараз його вирізняють напади неконтрольованої | metaphor | люті | ", – наводить видання зміст переданого |

| korrespondent.net | place’. </s><s> ‘He used to be restrained with his subordinates, while now he is distinguished by bouts of uncontrollable | metaphor | fury | ,’ the publication quotes the content of the referred |

In this example, the storm source domain is combined with the previously discussed illness source domain.

Other less frequent source domains include animal (verbalized with words like дикий, плекати); sound (звучати, слухати), sea (хвиля), arithmetic factor (помножений на…); container (наповнювати); and thirst (вгамувати).

Occasionally, fury is mapped metaphorically as a weapon, as seen in this example:

| 24tv.ua | " та вирішили налагодити їхнє виробництво на території нашої держави. </s><s> Ось вони, 152 мм нашої, української | metaphor | люті | . </s><s> Вже незабаром по всій лінії фронту. </s><s> Ловіть привіти, окупанти! </s><s> Привітів буде багато, – написали в пресслужбі |

| 24tv.ua | ‘ and decided to establish their production in our country. </s><s> Here they are, 152 mm of our Ukrainian | metaphor | fury | . </s><s> Soon they will be all over the front line. </s><s> Catch greetings, occupiers! </s><s> There will be many greetings,’ the press service wrote |

This metaphor can be modeled as a blend involving the generic space of war, with two input spaces – fury and artillery shells (caliber) – blending into the expression 152 mm of Ukrainian fury.

Thus, in Ukrainian media, fury is metaphorically construed as possession, person, resource, destination, object, subtance, content/fluid, cause, fire, illness, element/storm, animal, sound, sea, arithmetic factor, container, and thirst. Occasionally, it is also conceptualized as a weapon through conceptual integration or blending. It is important to note that the collocational data only partially reveal the full metaphoric potential of the concept fury. More precise results may be obtained through manual annotation, which is a direction for future research.

Conclusions

The article focused on the semiotic and cognitive potential of the concept fury realized in the Ukrainian language media in visual and verbal modes.

The implementation of the concept fury as a visual image revealed its references with such nation-building concepts as natural beauty, love, fragility, victory, honesty courage, invincibility, guarding, defiance, hatred/death to the enemy, unity, resilience, Ukrainian Kozak spirit (liberty), motherland, and sovereignity. This confirms its status as another nation-building concept in Ukrainian national construal of the world.

The multimodal concept fury from a semiotic prospective, is represented through all three fundamental types of signs: icon, index, and symbol. Since fury is an abstract concept, the distinction between the carrier of fury and fury itself allowed considering hybrid types of signs in terms of symbolic iconicity. As an icon, fury appears in portraits of both fictional and real figures of national importance, as well as in lexigraphic depictions. In its indexical form, fury is visually or lexigraphically linked to the historical land-marks of full-scale aggression or to notable figures, often through their characteristic gestures. Symbolically, fury is strongly associated with Ukrainian folklore and heraldic symbols.

In the capacity of a lexical concept verbalized in the Ukrainian unit лють, fury shows significant semiotic potential as both a symbol and an icon. As an icon, it is employed in its literal sense to denote a specific emotion. As a symbol, it is used to name military units and weapons. The concept’s indexical potential reveals itself through its metonymic use.

Cognitively, the lexical concept is implemented as metonymy and metaphor. Metonymically, fury is presented as booster or tool, a specific mental state, insanity, or physiological ways of its revealing, such as body shaking, teeth grinding, and fists clenching. It may also be presented as a specific social response, such as crying out loud, and lacking words. Metaphorically, fury is mapped as possession, person, resource, destination, object, subtance, content/fluid, cause, fire, illness, element/storm, animal, sound, sea, arithmetic factor, container, thirst, and occasionally, as weapon.

The concept’s multimodality, its verbalization by a hash tagged word лють that is one of socially significant words in Ukrainian media and its coreference with other national concepts underpin its status of a nation-building concept.

The limitations of the study include a scarce range of visual data, the Sketch Engine range of concordance that varies from month to month, and the metaphoric potential of the lexical concept fury that is still to be explored. The latter factor opens further perspectives for the research of this concept.