Introduction

In this paper we investigate the function of spatial adverbs or preverbs (hence SAPs) as used in combination with toponyms in nonstandard varieties of Alpine Gallo-Romance, Upper German, Slovenian, Hungarian, Burgenland Croatian and Romani. These SAPs symbolize the route between reference point and destination in form of a trajectory, and are illustrated in the following examples:

| (1) | i | fahr | nach | Graz | auf-ia | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| 1sg | go.1sg.prs | to | Graz.top | up-thither | ||

| “I go to Graz.” (questionnaire) | ||||||

| a. Note that the thither-morpheme -i is contrasted with a hither-morpheme -a in Austro-Bavarian German. The former indicates movement towards a location distinct from the deictic center, whereas the latter encodes movement towards the deictic centre. For example, ein-i translates as ‘into a location distinct from the deictic center’ and ein-a as ‘into the location of the deictic center’ (see Gruber, 2014, for a detailed discussion). | ||||||

| (2) | i | à | na | jormana | fora | (i)n | Puster | (Badiot Ladin) |

| 1sg | have | indef.art | cousin | outside | in | Pusteria valley.top | ||

| “I have a cousin in Pusteria valley.” (Prandi, 2015: 119) | ||||||||

| (3) | smo | Kethej | [...] | ovo | nutri | (Burgenland Croatian) |

| be.1pl.prs | Neumarkt.top | [...] | there | inside | ||

| “We went there, to Neumarkt.” (Tornow, 2011: 107) | ||||||

| (4) | jek | hi | avral | Betsch-is-te | sohar-d-i | (Burgenland Romani) |

| One.indef | be.3sg.prs | outside | Vienna.top-obl-loc | married-pp.f | ||

| “One is married in Vienna.” (Wogg and Halwachs, 1998: 33) | ||||||

| (5) | dol-taa | Maribor | se | pelj-em |

(Dialectal Slovenian from north-eastern Slovenia) |

| down-thither | Maribor.top | refl | go-1sg.prs | ||

| “I’m going to Maribor.” (elicitation) | |||||

| a. This dialectal adverb combines the directional dol ‘down’ with a thither-morpheme ta and thus resembles the Austro-Bavarian German combined directionals. | |||||

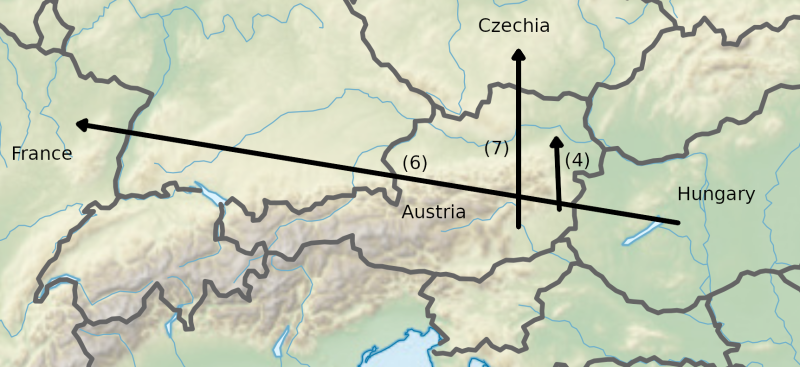

| (6) | ki-megy-ek | Angliá-ba | ki-megy-ek | Franciország-ba | (Hungarian) |

| outwards-go-1sg.prs | England.top-into | outwards-go-1sg.prs | France.top -into | ||

| “I’m going to England, I’m going to France.” (questionnaire) | |||||

| (7) | wi-ĕm | ĕmol | an | u | Béjmi | wri |

(Sinti Romani from Austria) |

| come-1sg.pf | once | to | def.art | Bohemia.top | outwards | ||

| “Once I went to Bohemia.” (Knobloch, 1950: 240) | |||||||

These SAPs are used when the remote place is explicitly named or when it can be deduced from the context. They are not used literally and there are regional differences in their application. They are neither analysable as synonyms for cardinal directions such as up for north nor as fixed expressions such as “Down Under” for Australia. A relation that is denoted with up may coincide with a northward direction or higher altitude but does not have to. Additionally, the hearer typically does not interpret one such SAP as offering directional or topographic content. Considering these conditions, the SAPs seem to convey redundant information. We suppose, however, that they are not redundant and thus we aim at answering the following research questions:

What exactly is the function of these SAPs and why are they used in this particular way in a range of typologically differing adjacent languages?

This paper relies on research data from questionnaires exploring how and why to use SAPs in combination with toponyms, spontaneous utterances and qualitative interviews, online sources such as internet forums, consultations with linguists1, and secondary literature. First, we compiled a preliminary questionnaire that we tested and subsequently refined under consideration of the difficulties presented in the test run (e.g. lack of clarity of a question, or ambiguous reading by the consultants). The questionnaire was distributed for German (21 participants aged 17‑78), Hungarian (53 participants aged 18‑75), Slovenian (34 participants aged 18‑63), and Prekmurje Romani (9 participants aged 9‑42). The questionnaire inquired about age as well as current and previous places of residence, and comprised 8 ensuing questions. At the outset, the participants were presented with uncontextualized SAPs and asked whether they were familiar with them. Subsequently, they were asked to produce sentences with “going to” and toponyms in the way they use them. The final part comprised contrastive examples, one with and one without a SAP. The participants were asked to choose the more appropriate sample, with the option to write down the reason for their choice following each example. At the closing, the questionnaire offered the option to write down additional thoughts on the matter as well as contact information in case they were interested in a personal interview.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 1, we will discuss the function of SAPs in the spatial domain, and in Section 2, we will demonstrate that their functional range goes beyond spatial orientation. In Section 3, we will examine how such combinations of toponyms and SAPs emerge. Section 4 investigates this phenomenon from an areal linguistic perspective and shows that it is by far more widespread than assumed heretofore.

1. SAPs as indicators of cognitive maps

There are several works on the use of SAPs in combination with toponyms. For German, the most comprehensive description can be found in Stadelmann’s (1978) monograph on the phenomenon in western Upper German varieties. Other notable works for German are Huber (1968), Rowley (1980) and Reichel (2003). Fazakas (2007, 2015) has examined the usage of preverbs in Hungarian from the 15th century onward and offers insights into how and why certain spatial preverbs have been used in combination with toponyms. Further research investigating the phenomenon in Hungarian has been carried out, inter alia, by Mátai (1992) and Szilágyi (1996). To the best of our knowledge, for Slovenian, there are only a small number of works that briefly discuss SAPs in the context of this usage (Isačenko, 1939; Reindl, 2008; Šekli, 2008). More recently, Prandi (2015) has examined the phenomenon in Alpine Romance dialects in Italy and Switzerland, defining it as a ground-oriented deictic system representing cognitive maps shared by a local community. Prandi’s paper also provides an overview of earlier works related to Romance varieties. However, Stadelmann (1978) has already noted that the reference point is not an egocentric origo (Bühler, 1982 [1934]) but is shared by a local community, such as the population of a valley or a town.

The social dimension of these SAPs has only been addressed marginally, for instance in Huber (1968: 33‑35) who mentions the negative connotation of hinterhin “thither back” in south-western Upper German varieties (cf. English “backward”). An exception to this is Fazakas’ (2007) work in which she analyses the urban/rural connotation of the Hungarian adverb pair fel/le “up/down”. Another remarkable work on the social dimension is Grill (2012) who examines the use of the corresponding adverb pair opre/tele “up/down” with regard to better living conditions for Roma in Great Britain in Eastern Slovak Romani varieties2 where opre is used when going to England while tele is used for the opposite direction.

Stadelmann (1978: 124‑126) makes the interesting observation that the SAPs used with toponyms refer to an additional “third place” that remains obscure and is thus often unclear or even disputed among speakers. Thus, the local adverb avral “outside” in (4) not only refers back to the home village of the speaker in Burgenland through shared knowledge but also to a third place “outside” of which Vienna is located. This third place may coincide with the reference point such as in (4) where the village is imagined as located within a container, and Vienna as being situated outside of said container (see Figure 2). In (1), on the other hand, the SAP up seems to refer to the flow direction of the Raab river (see Figure 1 and Section 3), i.e., that “third place” is located between the reference point and the destination.

Figure 1

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Figure 2

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Considering Levinson’s (2003) typology of spatial referential strategies, the SAPs in combination with toponyms are particular since they, by themselves, do not provide angular information – a prerequisite for Frames of Reference (hence FoR). FoRs encode where a goal (or entity) is located relative to a source reference by employing one of three perspectives: relative, intrinsic, or absolute. As toponyms are anchored in absolute space, one might assume that the speaker employs an absolute FoR in the present case, but typically, these SAPs encode a relative FoR between communities since their referential specificities differ from region to region and encode a speaker’s (or community’s) perspective. Comprehending what the SAPs as used in a respective community refer to is only possible for someone who has access to knowledge shared by that community. In this sense, within the community – or within certain groups of the community – speakers may interpret SAPs as having an absolute reading, since specific SAPs are used for fixed directions/regions. However, more often than not, the interpretation of the SAP’s reading is a matter of vigorous debate within communities (especially intergenerationally) as well as between communities (but see Section 3 for a general shift to an absolute FoR reading).

Whether or not speakers are aware of or have an opinion on what a certain SAP refers to (a certain valley form, movement towards the main town, etc.), they merely represent abstractions of the actual route. These abstractions reduce the path through terrain to trajectories that can be described with image schemas (see Lakoff and Johnson, 2003). Vertical orientation metaphors (up/down), for instance, may refer to the Alps; hence, in south-western Germany, up in many cases denotes a southward direction (see Stadelmann, 1978: 318). The containment metaphor of Vienna being outside in (4) is used similarly to the Hungarian ki “out”, often referring to places outside one’s own village, which is imagined as a closed entity (Fazakas, 2015: 52‑53).

As said before, the SAPs only provide angular information if the hearer is aware of how they are used in the speaker’s community. For instance, going up to Graz in (1) cannot be understood by somebody who does not know that Graz is imagined as up in eastern Styria. In such a case, the hearer cannot deduce the source and triangulation point within the FoR, as this depends on knowledge of SAP choices in that region. The same is true if no toponym is named or if it cannot be deduced from the context. Just telling somebody to go “down” has a myriad of meanings since it remains unclear what is meant by “down”. The SAPs, thus, cannot be used as pro-forms unless the toponyms they refer to have been mentioned earlier or are deducible from the context.

The SAPs also encode spatial deictic information. Applying a threefold distinction, the choice of an SAP determines whether the speaker considers the toponym as proximal, medial or distal to the origo. As with the trajectories discussed above, the deictic interpretation of an SAP is region and community specific, with a prominent example being umhin “(horizontally) across.” It can denote both proximal, medial and distal meanings, as seen in its usage in dialectal German in Oberviechtach, Bavaria. It is used for both close locations on roughly the same altitude, places separated from the reference point by an obstacle, and faraway locations such as the USA (see Wohlgemuth and Nachtmann, 1980: 221‑222). Out, on the other hand, has been described as conveying distality by one person from Western Styria (the foothills of the Alps west of Graz):

| (8) | Wien sagt ma “außi” weil es weit is; weil ma halt aus dem Zentralgebiet wo ma normal is weg fahrt. | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| “One says ‘out’ to Vienna because it’s far away; because one goes away from the central area where one usually is.” (questionnaire) | ||

This observation resembles the way out is used in the Burgenland Romani (4) and Hungarian (6) samples. However, in south-western German varieties out is also used for locations perceived as proximal or medial, namely for routes towards the flatland from the perspective of mountain villages (see Stadelmann, 1978: 342‑343).

Typically, the assignment of specific SAPs to particular toponyms is agreed upon within a community. Despite this general tendency, exceptions exist: even within families, different choices of SAPs with the same toponym and distinct FoR codings may coexist side by side. One of our interviewees, whose family resides at the foot of a mountain pass in the Austrian Alps (Pyhrn pass), has noted variations in her family’s selection of SAPs in conjunction with Vienna. She uses up (“Wien aufi”), while other family members either use across (“Wien ummi”) or down (“Wien owi”). Vienna lies roughly 700 meters lower than the reference point, which could explain the use of the SAP down. In contrast, the SAP across, among other things, may refer to terrain with obstacles. The family member employing across is reported to frequently travel to Vienna and to feel a familiarity with the city. Considering this, the choice of across can be understood as conveying perceived proximity. However, the interviewee herself noted that she interprets the SAPs as referring to cardinal directions (see also Section 3) rather than the surrounding topography or the topographical differences between the Alps and the position of Vienna in a basin to the east of the Alps. Thus, when she uses up, she refers to a position to the north of her family’s home. Nonetheless, Vienna lies significantly more to the east than to the north of the family’s home. Interestingly, she seems to be aware of this and gives an explanation for the family member’s choice of across:

| (9) | weil er genau weiß dass [Wien] auf der Landkarten mehr ummi als aufi is. | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| “because he knows exactly that on a map, [Vienna] is more across than up.” (interview) | ||

2. SAPs as pragmatic device

Different from the early debate in cognitive linguistics on linguistic vs. environmental primacy in spatial encoding, more recent approaches (e.g. Bohnemeyer et al., 2014; Dasen and Mishra, 2010) propose an intermediate stance: Even if spatial thought is not utterly determined (and determinable) by the respective surrounding environment, the environment does play a partial role (see Palmer et al., 2017: 458). The fact that the SAPs make both geographic and social references supports the intermediate stance. They are not rooted in geography alone, but refer to the sociogeographic situation of a community. This rootedness in both the social and geographic spheres is well illustrated in the explanation of why the term owi “down” is used, as uttered by the same person as in (8):

| (10) | Von St. Stefan fahren die Leut nach Stainz “owi”, da wo’s zu die Tschuschn geht; und es geht bergab. | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| “From St. Stefan the people go ‘down’ to Stainz, there where the way leads to the Tschuschn [derogatory term for the inhabitants of former Yugoslavia]; and it goes downhill.” (questionnaire) | ||

The use of the derogatory term “Tschuschn” for the neighbouring Slovenes implies a distinctly negative social reference conveyed by the SAP down, even extending to locations in that direction within Austria. The use of down is then further explained by a geographic argument, namely, the observation that the route between the two places literally leads downwards. An interesting point in comparison with (10) is the observation of the use of up, conveying a positive social reference in Hungarian:

| (11) | Nyugati országokra másképp tekintünk, pedig nem feltétlenül északra, “felfelé” van, hanem “balra”, mégis felmegyünk, valahogy felnézünk, nem földrajzilag viszonyítunk. Annyiszor hallottam Bécsre, Párizsra. Aztán akadnak számomra kicsit szándékosnak tűnő kifejezések, amelyek kicsit alárendeltséget mutatnak, mondjuk Romániával kapcsolatban. Míg sokan Sopronból felmennek Bécsbe, Budapestre, Velencébe, Bukarestbe nem. | (Hungarian) |

| “We look at Western countries in a different way, although they are not really in the north, ‘upwards’, but ‘to the left’, we still go up, somehow we look up, we do not orient ourselves geographically. I’ve so often heard that for Vienna, Paris. Then there are expressions that in my opinion sound a bit deliberate, that show a bit subordination, for instance in combination with Romania. From Sopron many people go up to Vienna, Budapest, Venice, but not to Bucharest.” (questionnaire) | ||

This demonstrates that the geographic and social references are not exclusive but complementary. The SAPs can serve as abstractions encompassing a multitude of references within space. In other words, these SAPs represent linguistic manifestations of the perceived environment. Their accomplishment is not so much the cognitive mapping of remote places but perspectivization (see e.g. Geeraerts, 2006) based on one’s home region. This means that they act as pragmatic devices allowing a speaker to signal the hearer to interpret an utterance from a certain sociogeographic perspective. Based on that, the SAPs enable speakers to locate themselves in space by their relation to remote places, as is illustrated through the following sample:

| (12) | Auf Graz owi. Auf Liazen owi, auf Schladming aufi, auf Aussee eini. Und auf Salzburg außi. Hiatz wissts, wo i dahoam bin. | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| “Downwards to Graz. Downwards to Liezen, upwards to Schladming, inwards to Aussee. And outwards to Salzburg. Now you know where I’m at home.” (internet post)a | ||

| a. From an internet survey on SAPs carried out by a private radio station, https://www.facebook.com/antennestmk/photos/a.10150742113181779/10158879833451779/?type=3 (22 November, 2023.) | ||

Furthermore, data from our questionnaires indicate that – at least in Austro-Bavarian German – the SAPs also denote aspectual telicity (see Moser, 2014: 115‑116) and return path (Wilkins, 2006: 41). As a speaker of Austro-Bavarian German from Graz pointed out, the directional in a phrase like noch Wian außifoahrn “to go out to Vienna” also implies returning to the home region at some point in the future, i.e. the motion event is timely limited and ends at the reference point. The notion of return is well illustrated in (13). The question was whether or not to use the SAP außi “outwards” when going to Germany and returning the same day:

| (13) | außi-> dann muß [sic] wieder “eini” kommen | (Austro-Bavarian German) |

| “outwards-> then one must come ‘inwards’ again” (questionnaire) | ||

This finding resembles the semantics of the SAPs in Hungarian where they are used to denote perfective aspect (see Forgács, 2004; Knittel, 2015). While a sentence like Mentem Budapestre is understood as “I was on the way to Budapest”, the same sentence with the preverb fel “up”, Felmentem Budapestre, means “I went to Budapest [and I am there now, or I was there and I am back home again].”

3. The life cycle of a SAP

Each relation expressed by a SAP, for instance Maribor being “down” from the perspective of the village in north-eastern Slovenia in (5), has a certain origin. Somebody must have perceived it that way and this perspective must have spread among the community. Thus, the emergence of a new relation expressed by a certain SAP is based on personal experience or, as one of our interviewees put it, on gefühlte Richtungen “felt directions”. An illustrative example for the emergence of a new relation expressed by a SAP based on perception is the utterance of a three-year-old boy about the route to his childminder.3 The boy’s home is located on a hill range between a village and Graz where his childminder lives. While walking through the village with his parents, he remarked that his childminder lived up there (pointing to his home) and that from home there is another road leading to the childminder. Coming from the direction of his home, the childminder lives down the hill, prompting him to explicitly state that there is an additional road since up only refers to one part of the way. At this first stage of experience, using a certain SAP is individual and may become part of community knowledge if accepted, at least partly. As Stadelmann (1978) shows, in most cases, there is general agreement in a community which SAP to use with certain toponyms, while in others, several SAPs are used side by side. Once in frequent use, the use of a certain SAP enters the second stage, tradition. As mentioned above, the reasons for the assignment of a specific SAP to a specific direction can become obscure for a community over time. Our elicitations and questionnaire data on why a certain SAP is used yielded answers like “that’s just how we say it”. At this stage, the SAPs might have already been handed down over generations and may point to old routes not used any longer (e.g., due to new roads, see Reichel, 2003: 24). They evolve into shared knowledge that is independent from personal experience. The third stage is the transfer of established SAPs onto new locations, which we term analogy. Obviously, not every place in the world is assigned an SAP in the perceived environment of a certain community. But as soon as a place gains significance in discourse, it may enter the system by being assigned the same SAP as that of a place close to it, or more precisely of a place experienced as close to it. Thus, analogy leads to the emergence of regions that are referred to by a single SAP (see also Stadelmann, 1978: 317; Tyroller, 1980: 70).

Huber (1968) equates the use of SAPs with a down-to-earth attitude and their absence with rootlessness. Later works are less essentialist and explain the decline with greater mobility and the growing influence of the respective standard languages. Cognitive linguistic research shows that there are differences in the use of spatial language within language communities. These depend on culturally and socially induced factors interacting with environmental features. For instance, Danziger (1999) shows that Mopan (Mayan) fieldworkers employ cardinal directions more often than those working in the house or village. Along these lines, Shapero (2017) shows that in a Peruvian community, those who had worked as herders in the surrounding Andes exhibit more geocentric referential strategies than those who had not. Palmer et al. (2017) illustrate that spatial expressions in Dhivehi and Marshallese seem to have a stronger tendency to be connected to the topography of the land if speakers commonly move through and interact with the environment; urban centered speakers show a weaker tendency to use spatial expressions in that way. Our data show a similar situation: People living in urban centers repeatedly reported to be aware of the usage of SAPs by other speakers, but that they themselves were not using them. The reason not to use them can, however, be based on deliberate choice too. One interviewee described using them as “rural” and “dialectal”, something she has striven to distance herself from ever since moving to an urban area. She pointed out repeatedly not to use them, not to be able to “relate” to them and also not to know which SAP might be used with which location as she had never “learned” them. Ultimately, however, she recalled quite vividly which SAPs inhabitants of her birthplace used.

There also seems to be an ongoing change of what SAPs refer to, or how they are decoded, respectively. While some keep using and understand them as encoding a relative FoR based on within-community knowledge, others interpret them as references to cardinal directions. This may lead to a shift towards an absolute or geocentric FoR reading (see also Bohnemeyer et al., 2022) that is no longer dependent on community knowledge. In other words, younger generations tend to interpret up/down as cross-community proxies for north/west and across for east and west (cf. the discussion of one interviewee’s interpretation in Section 1). A discussion between two German speakers from south-eastern Styria in their thirties triggered by the question about which SAP to use when going to Hungary illustratively shows this ongoing transformation: One person said to use Ungarn ummi “across to Hungary” since it lies to the east. He then stated that he identified north with aufi “up” and south with owi “down” while using ummi “across” for east and west. This has been opposed by another person insisting that one goes owi “down” to Hungary, based on the Raab river rising from the eastern fringes of the Alps and flowing eastwards to Hungary. Another example shows, however, that SAPs may only be reinterpreted partially: A woman from western Hungary, around 80 years old, reported to orient herself according to cardinal directions when using SAPs in combination with toponyms. Consequently, for her Croatia was down and Slovakia was up. Upon the question about the position of Austria (west) and Romania (east) she stated, however, that they were outside, employing the relative FoR containment metaphor.

4. SAPs as an areal feature

SAPs used in the particular way described here are found in southern Central Europe in varieties from all major European language families (Finno-Ugric, Germanic, Romance, and Slavic) and an Indo-Aryan language (the Romani varieties spoken in the area). We did not, however, find traces of them in surrounding Czech, Slovak, Romanian as well as other Romance varieties in northern Italy. This includes Friulian, a Romance language spoken in a region adjacent to Austria and Slovenia. On the Slovenian side of the border, however, the existence of SAPs with toponyms in the local Slovenian variety is confirmed by Šekli’s (2008) research. Our data show, in line with the existing literature, that in German, Romance and Slovenian varieties the use of SAPs is gradually decreasing the further away a variety is from the Alps.

Studies in which SAPs are characterized as an areal phenomenon are available for Romance-German (Huber, 1968; Stadelmann, 1978; Rowley, 1980, Gaeta and Seiler, 2021; Bernini, 2021) and Slovenian-German (Isačenko, 1939; Reindl, 2008). These works focus on small bilingual regions in the Alps and describe using SAPs with toponyms as language convergence caused by the Alpine topography. To the best of our knowledge, there is no source on using SAPs with toponyms as areal phenomenon that includes Burgenland Croatian, Hungarian and Romani.

SAPs are not the only linguistic feature that has been discussed as areal phenomenon in Central Europe. Newerkla (2004) gives a comprehensive overview of theorizing a Central European or Danube sprachbund. Kiefer (2010) proposes a linguistic area that is characterized by the use of prefixes and/or preverbs providing verbs with aktionsarten. That area comprises the Slavic languages, Hungarian, German, Yiddish and Romani varieties spoken in the respective regions. Recently, Gaeta and Seiler (2021) have suggested an Alpine sprachbund based on structural similarities, including SAPs used with toponyms.

Local multilingual communities in the Alps indeed share the same ecology and, as we have noted before, the Alps appear to be the core region of using SAPs with toponyms, at least for German, Romance and Slovenian varieties. Stadelmann’s (1978) comprehensive analysis shows that in the flatland the references to topography apply to larger areas than in the mountains. Fazakas (2007, 2015) shows, in line with Stadelmann’s observation, that in Hungarian references to settlements and rivers are more common with regard to SAPs than those to altitude. However, Berthele (2006: 215) reminds us that an equation of a mountainous home region and the use of SAPs with toponyms does not take into account the existence of this phenomenon in southern German varieties outside the Alps and the fact that the frequent use of SAPs in German is not bound to topics involving the own topographic environment. As we have elaborated in Section 2, a purely topographic analysis fails to capture the functional range of SAPs. Similarly, assuming one type of salient topography to be the source for their emergence fails to explain why SAPs used with toponyms are found in topographically highly diverse regions of southern Central Europe, especially when considering Hungarian which is primarily spoken in the Carpathian basin, a region that forms a stark contrast to the Alps.

Another approach is to consider directional language contact, i.e., to presuppose that using SAPs with toponyms emerged among a certain, perhaps bilingual, community and later spread to adjacent languages. Since no SAP is borrowed directly in any of the languages, the spread of using SAPs in this particular way would in such a scenario be a form of pattern replication (Matras, 2020), a creative process in which speakers rebuild a linguistic structure from a source language with its closest match in the target language. Another possibility is that one or more languages of the region have caused the others to undergo metatypic restructuring of the semantics of SAPs as it has happened on North Maluku Island where local Malay speakers use Malay directionals to express the ground-based orientation system used by the local indigenous population (Bowden, 2005).

Regarding time, Huber (1968) was able to trace SAPs used with toponyms back to the Old High German period and Fazakas (2007, 2015) found them in Hungarian sources from the 15th century onward. Prandi (2015) even hypothesizes that they are the source for particle verbs in Romance varieties in northern Italy. This is, in turn, opposed by Bernini (2021: 64) who submits that the SAPs have a higher prevalence in German-Romance bilingual areas. If we assumed the Alps to be the origin of this phenomenon, it would imply that remote Alpine German varieties spoken by relatively few people have substantially impacted the surrounding densely populated regions. However, Bernini (2021: 42) shows that the opposite is the case. It rather seems to us, that using SAPs with toponyms has been best preserved in the Alps.

Due to the lack of sufficient historical data from the languages discussed, the theories on the emergence and spread of this way of using SAPs in southern Central Europe must remain speculative. The phenomenon clearly shows areal distribution affecting some varieties of the languages involved while being absent in others (see Aikhenvald and Dixon, 2001), with Hungarian being the language in which they are most prevalent.

Finally, one intriguing feature of this phenomenon is that it occurs independently from the typological composition of the languages involved. This is also true for German and Hungarian where the spatial adverbs syntactically behave as preverbs. But since they can be used without a verb as well, they are, in fact, independent adverbs. In all of the varieties examined, a toponym is accompanied by a SAP. The toponym can only be omitted when both speaker and hearer know the place referenced and when they can deduce it from the context during a conversation. This similarity among languages with substantial typological differences (Finno-Ugric, Germanic, Indo-Aryan, Romance, and Slavic) leads us to the conclusion that the functional dimension of these SAPs has a higher impact than the topography surrounding the speakers. Stadelmann (1978) has shown that topography helps to understand why a certain SAP is used for a specific relation. Topography, however, does not shed light on the question why such constructions are used at all, i.e. why people in mountainous regions such as in the Swiss Alps use them in the same way as people living in plains such as in the Carpathian basin.

Conclusion

Using SAPs with toponyms might seem outmoded nowadays given that most of us are equipped with a portable navigation system. But using them goes beyond spatial orientation, as they, first of all, facilitate a form of sociogeographic perspectivization that is accessible to those who share knowledge of a certain region and/or the social situation of a certain community. People use them to share with others their perspective from a common reference point. The SAPs always say more about oneself than about the remote destination that a certain SAP has been assigned to. This allows people to position themselves and their utterances within sociogeographic space based on the spatial and social reality they find themselves in. When used with motion verbs, the SAPs are a means to denote timely closed actions that begin in one’s home region and also end there.

We have discussed in Section 4 that purely geography-based explanations for the spread of this phenomenon are problematic. Auer (2021: 150) suggests that in connection with the study of deixis and discursive structuring in language contact situations the question to ask is “which pragmatic needs of the speaker are so pressing that the relevant structures of one language are copied into the language that undergoes contact-induced change?” The SAPs are capable of structuring discourse in a way that allows speaker and hearer to share their personal spatial experience by drawing on SAPs. Their reference to a shared sociogeographic reality renders them difficult to translate, as translating rather than replicating them would substantially increase the cognitive load (Matras, 2007) for a multilingual individual. We therefore conclude that it is not the landscape but their functional range that drives speakers to use SAPs in this way cross-linguistically. Their concrete morphosyntactic integration as either independent adverbs or preverbs does not interfere with their extralinguistic reference and thus offer a practical means of anchoring oneself and that what is said within a world view shared by one’s community. Using a seafaring metaphor, the SAPs are anchors in sociogeographic space and thus a way to experience the world together from a certain place in the world, regardless of how far away one is from that place.

Abbreviations

1PL: 1st person plural

1SG: 1st person singular

3SG: 3rd person singular

ART: article

DAT: dative

DEF: definite

F: feminine

FoR: frame of reference

INDEF: indefinite

LOC: locative case

OBL: oblique case

PF: perfect

PP: past participle

PRS: present

REFL: reflexive

SAP: spatial adverb or preverb

TOP: toponym