Mythology of the animal kingdom (including insects) manifests itself both by shapes of special fantastic creatures and by entering of common classes of animals into the mythical structure of the world as well as establishing their relationship with mankind. People are not the only ones with ideas about the natural world, i.e. representatives of the latter interpret people in a mythical manner and express their views accordingly. The present article focuses on one small and unfriendly creature called kurklys or kartas “the mole cricket” which would kill the man, if it only could: “The mole cricket […] is thinking nine thoughts and then bites the man. The bitten person must die and nothing can save him [her].” (Elisonas, 1932, p. 32) The mole cricket is even called an insect who thinks nine thoughts (in Lithuanian devyniamislis): “It is called the one thinking nine thoughts as it has that many thoughts and the ninth thought is the most dangerous one.” (LTR1 374d/1984‑52).

The present article based on the Lithuanian materials is intended to reveal the mythical nature of the mole cricket and its relationship with other classes of the animal kingdom as well as its role in the Lithuanian ethno-medicine. There is an unquestionable correlation between the mythical insect and a healing ritual based on symbolic analogies, where curing methods are chosen taking into account physiological aspects of the mole cricket perceived through mythological categories.

Since almost no data on the mole cricket has been published (a few folk beliefs can be found only in the publication of Jurgis Elisonas about the Lithuanian fauna in folklore, see Elisonas, 1932), the research is based on the data from the Lithuanian Folklore Archives and the field study recorded by the author.

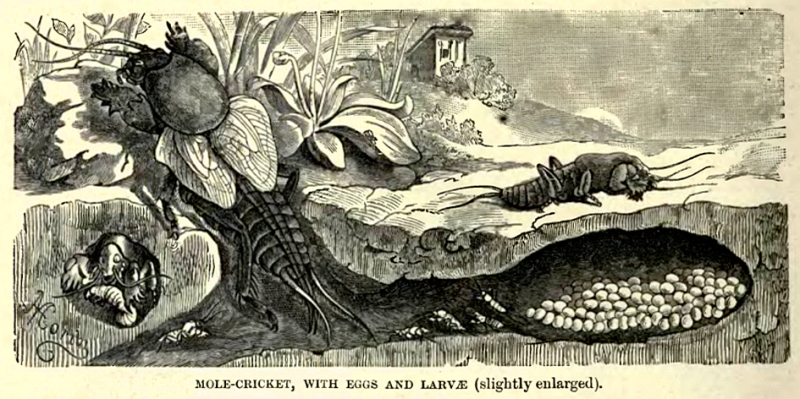

Figure 1. – Mole cricket.

Photo by Algirdas Vilkas, 2008.

Ethno-zoological definition

The one who thinks nine thoughts or the common mole cricket is an insect which lives underground, surfacing from its tunnels at night; it feeds on plants and often eats away roots of young vegetables, spoils potato tubers. This is the mole cricket definition provided by Wikipedia2:

One of the most impressive and unusual looking insects. […] The body is brown in colour and covered with fine velvety hairs, and the forelegs are greatly modified for digging. Only the adult stages are winged, and flight is said to be clumsy, directionless and only performed on rare occasions at night. […] This mole cricket occurs throughout Europe, except Norway and Finland, through to western Asia, North Africa and South Africa.

[…] Adults and nymphs can be found throughout the year in extensive tunnel systems that may reach a depth of over one metre. Mole crickets are omnivorous, feeding on a range of soil invertebrates and plant roots; often leaving neat circular holes through the roots of tuberous plants. Males occasionally produce a soft, but far‑carrying ‘chirring’ song from within a specially constructed chamber in the burrow system, which acts as an amplifier for the song, which is likely to be used for attracting females. The song is typically produced on warm mild evenings in early spring between dusk and dawn, and it is similar to the song of the nightjar Caprimulgus europeaeus. (“Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa”, 2008)

We may only add to this definition that it is a truly large insect as its body may be up to 55 mm length. An insect of such size and threatening appearance can be easily noticed and is very well known to people in rural areas of Lithuania or to town residents who enjoy gardening.

The Lithuanian names for the mole cricket kurklys, parplys and turklys are associated with the sound it produces: on humid summer evenings, especially before the rain, mole crickets make a sound which is described by Lithuanian verbs kurkti, parpti, turkti (LkŽe) (something like chirring, purring or croaking). People easily recognize the voice of the mole cricket and can tell it from chirping of grasshoppers, crickets, crocking of frogs and similar sounds.

Due to the ability to poison people attributed to the mole cricket (although unconfirmed by modern biology) this insect in Lithuanian ethno-zoology is compared to the scorpion which though in fact does not occur in Lithuania, but people have been hearing about it from church sermons or readings of the Holy Writ since the fifteenth–sixteenth centuries. Although the scorpion in modern Lithuanian is called skorpionas, in the Lithuanian written texts of the sixteenth–nineteenth centuries, before the scientific zoological terminology was defined, the scorpion was sometimes referred by the Lithuanian names of the mole cricket, i.e. kurklys and parplys.

There are a few other animals closely associated with the mole cricket. Visually because of its well-developed forelimbs by which it shovels earth the mole cricket is compared with the crayfish (LTR 374d/1984‑52; LTR cd 191/7). As a contrast, the crayfish is sometimes called the mole cricket (LKŽe: kurklys). Latvians refer to the mole cricket simply as the crayfish: zemesvēzis “the crayfish of the earth” (Muelenbachs, 1932, p. 574; also cf. German, erdkrebs). A similar name is known to Slavs, cf. Russian zemlyanoi rak the “crayfish of the earth”, Ukrainian rak, rachok, rak zemlyanyi “the crayfish, little crayfish, the crayfish of the earth”, Bulgarian div rak, rachets “the crayfish” (Gura, 1997, p. 521).

Another significant association links the mole cricket to the mole: both animals dwell underground and dig tunnels. As we will see their association is based both on biological similarity and similar ethno-medical functions. The fact that the mole cricket is linked to the mole is also indicated by the former’s Latin name and its analogies in European languages: Lat. Gryllotalpa originated from gryllus “cricket” and talpa “mole”; cf. English “mole cricket”, German Maulwurfsgrille. The mole cricket is called the mole (krot) in Podlachia region of Poland (Gura, 1997, p. 521).

Figure 2. – The life cycle of the mole cricket.

Drawing by Richard Lydekker, 1879.

Nine thoughts: number and process

A distinguishing feature of the mole cricket in the world of insects is its lengthy and slow process of thinking, i.e. its nine thoughts, where the resolution of this process (a bite) may be lethal to the man: “They say that the mole cricket is thinking nine thoughts and at the tenth it already [bites]. It may be a deadly bite.” (LTR cd 188/02)

Malicious intention is one of the major cultural senses of the mole cricket, cf. the saying nežinia, kų tu cia mislini, kap kartas “Who knows what you are thinking about like the mole cricket” (LTR 7043/149) is said when a person is suspected of secretly scheming something. However, since the mole cricket is thinking nine times, it bites very rarely or does not bite at all (LTR 7043/149).

It is sometimes believed that nine thoughts are merely a period of time during which not the mole cricket, but a person manages to think through nine thoughts; if a person thinks ten thoughts in front of the mole cricket, he/she will be bitten by the mole cricket and will have to die (LTR cd 190/7).

Thoughts of the mole cricket are perceived as a certain repetition, rethinking of the same evil thought. While rethinking the mole cricket’s malice is growing and the ninth thought is considered the most dangerous (LTR 374d/1984‑52). Thinking nine times is a process enhancing the venomous power of the mole cricket, a certain “magical practice”. A similar technique of repetition is used by Lithuanian charmers for curing diseases: the text of a charm is repeated 3 or 9 times in the belief that the power of the charm grows dependent on the number of times it is repeated. It is believed that the more times the charm is said, the more it helps (Lietuvių užkalbėjimai, 2008, p. 428).

Sometimes assessment of the mole cricket’s virulence is based on broader categories of time and the mole cricket is assessed in terms of its age. It is believed that if the insect has lived a certain number of years, it is becoming dangerous. A mole cricket of seven years is becoming poisonous and if it bites at that time, the person does not get well (Elisonas, 1932, p. 32). The number of the years lived in the Lithuanian mythology is associated with certain mythical transformations; for instance, aitvaras (a type of a brownie which looks like a flying fiery snake and brings wealth to the man) can be hatched from an egg laid by a seven-year-old rooster (Greimas, 1990, p. 182).

In terms of number symbolism it should be noted that 7 and 9 in the Lithuanian culture often replace one another. In folklore they can be interchangeable in similar situations, e.g. referring to someone who is feeling very well it is said kaip devintame danguje “like in the ninth sky” or kaip septintame danguje “like in the seventh sky” (LKŽe: dangus). Still the number 7 in the Lithuanian culture came somewhat later through the literary tradition of Europe and replaced number 9 in quite many places. The number nine is typical in folklore texts and symbolically means a lot, abundance and even infinity.

The mole cricket which becomes poisonous at the age of seven may be compared with the snake which crawls out to the surface every seven years and is very powerful and its bite is lethal. Such snake cannot be charmed since according to one snake charmer it does not obey to “your curse” any longer (Balkutė, 2003, p. 195).

The bite of the mole cricket is almost equaled to the snake bite (LTR cd 190/7). It is said that when one sees a mole cricket, he/she must kill it; similar actions are taken against a snake, but beating of a snake has clear motives: it is believed that if you kill seven snakes, your sins will be forgiven (Elisonas, 1931, p. 109). If anyone sees a snake and does not kill it, the Sun does not shine on such person for nine days (Elisonas, 1931, p. 108). Although in the Lithuanian folklore there is no data that after you kill a mole cricket, your sins are forgiven, but analogies can be traced in the Slavic folklore, e.g. according to Lusatians nine sins are forgiven to a person who kills a mole cricket (Gura, 2004, p. 211).

Sometimes the mole cricket as any other creatures bearing toxic substances is considered venomous for a certain period, for instance, it is said that “a bite of the mole cricket is harmful to a person only before St John’s Day” (LKŽe: turklys). The same applies to the snake venom which is particularly dangerous in spring, i.e. the snake of March has the strongest venom (Elisonas, 1931, p. 112). It is particularly important that a snake should be caught by the first song of a cuckoo. They believe that a snake caught before the cuckoo song is a remedy for rabies (Elisonas, 1931, p. 124). Meanwhile the cuckoo song does not impair poison of the mole cricket and its curative power as the mole cricket of May is believed to be especially suitable in the folk medicine (LTR cd 189/7).

Clostridium tetani

After a discussion of the venomous nature of the mole cricket and the lethal danger it represents, it should be noted that poison of the mole cricket is a mythical rather than biological category. According to entomologists the mole cricket is an absolutely harmless insect unable of stinging (Mole cricket, 2005). Only if a mole cricket is squeezed, it may slightly graze the skin without any actual danger to the person.

Yet in an attempt to harmonize different views of ethno-zoology and scientific zoology we should not look for the answer in the mole cricket biology, but rather in the circumstances of its contacts with people. Naturalist Ilmārs Tīrmanis suggests that even though the mole cricket does not have venom, it may be a carrier of dangerous bacilli which through the microscopic wound made by the mole cricket may cause a tetanus infection (Tīrmanis, 2004). People usually find mole crickets in gardens or potato fields and they are brought into a surface when ploughing or digging. Crawling through its tunnels, touching the earth and feeding on invertebrates living underground, this insect may carry in its mouth the bacilli of tetanus Clostridium tetani. Those bacilli may be found in the soil fertilized by manure, i.e. gardens where people often notice mole crickets. Clostridium tetani bacilli produce highly toxic substances which on contact with the wound can cause tetanus.

Tetanus begins as a wound infection and manifests by a severe intoxication of the body and muscle convulsions. Before the era of vaccination it was nearly always terminal. Even nowadays four to six people on the average catch tetanus annually in Lithuania and globally 200–300 thousand people a year become victims of tetanus (Stabligė, 2005).

In addition, the bite of the mole cricket may cause infections of another type or local inflammations. There is data evidencing that when a mole cricket bites a bare foot, a refractory blain appears (LKŽe: kartas).

Thus the mole cricket though biologically without venom, can cause a life-threatening infection. That might be the objective grounds for the myth that the mole cricket is thinking how to kill the man.

Imagining that a bite of the mole cricket is deadly is not a purely Lithuanian phenomenon, it is also found in the Slavic context. For instance, the Poles also believe that the mole cricket is venomous and a person dies from its bite: if you step on a mole cricket barefoot, your foot would wither; if urine of a mole cricket falls on your body, that place would begin to rot. It is also believed that one should not beat a mole cricket as the other mole crickets would have their revenge (Gura, 2004, p. 211).

Ethno-medical aspects

Some Lithuanian informants of the twenty-first century claim that there is no medicine for a bite of the mole cricket. However, one almost magic cure is known, namely gold. The author of the article in 2008 recorded this story about the use of a gold coin:

They say if you have been bitten, there is no remedy for you. Only gold. I remember that my mother used to have a small coin. One of the farm hands got bitten, [he] says: “I was pasturing a horse when I fell asleep and got bitten.” It swelled terribly. Everyone was saying that he had to be bitten by a mole cricket. They say: “See, if that is its bite, you will understand at once.” [They] were pushing [the coin] around and when it reached the bite spot, the little coin got stuck! He swelled even more, the coin became hardly visible. Then the swell of the arm subsided and the coin fell down. Nobody needed any medicine or a doctor. (LTR cd 187/02)

Doctors can say why gold decreases swell and infection in terms of medicine, but we should place this healing method into the general ethno-medical perspective the coherent principles of which are based on certain relations among elements of the world and animal communities. For instance, when healing erysipelas (a skin infection indicated by a bright scarlet spot, pain, swelling and fever), dark objects are used, i.e. black wool or blue paper is placed on the wound; it parallels to quenching fire (which causes erysipelas) by the earth (Vaitkevičienė, 2001, p. 41). Whereas in the case of the mole cricket we see a contrary phenomenon when healing is administered by gold which is one of the brightest mythical forms of fire (Vaitkevičienė, 2001, p. 53). The mole cricket is a chtonic insect which lives underground and even the nature of the bacteria it probably carries is earth-related as Clostridium tetani are found in the soil. Therefore, the opposite element, namely the fire, is chosen for healing this “earthly infection”. In fact, gold is used for healing of skin infections in other cultures as well, e.g. Albanians of Italy heal skin disease risibola, by gold, placing a golden coin on the skin (Pieroni, Quave, Nebel et Michael, 2002, p. 238).

However, in terms of ethno-medicine it is not only the healing of the mole cricket’s bite that is important, but the contribution of the insect to ethno-medicine. Despite a lethal danger presented by this insect and maybe because of that danger (as each venom is also a cure for some disease) the mole cricket has an exceptional significance. It is used in two ways: 1) as a folk medicine means, remedy for certain illnesses; and 2) as a mythical animal able to endow humans with extraordinary powers of healing.

The first case is not unusual since in the folk medicine and veterinary medicine various animals and their body parts can be used as medicine. Powder of a dried mole cricket or its alcohol tincture was considered suitable for internal use. For instance, the mole cricket tincture was taken to cure a disease of intestines called gumbas (Elisonas, 1932, p. 32). A dried and powdered insect was given for horses to drink in order to cure a horse disease of intestines called vansočius (LTR 374d/1984‑52; LTR cd 187/02).

The mole cricket as a medicine for internal use was known to Latvians as well. Alcohol-based tincture of the mole cricket was used to cure malaria (Latviešu tautas ticējumi, 1940, vol. 1, p. 375), epilepsy (Latviešu tautas ticējumi, 1940, vol. 2, p. 948), when baked into bread it was given to animals so that they can stay healthy (Latviešu tautas ticējumi, vol. 2, p. 1104). The mole cricket was fed to horses to maintain their health by Byelorussians and Russians: a black mole cricket would be fed to a black horse, a browner mole cricket would be fed to a bay horse and a pale yellow mole cricket would be administered to a light-bay horse (Gura, 2004, p. 211).

The mole cricket is also used as an antidote for a snake bite (LKŽe: turklys); here a homeopathic principle is clear: one venom is used to cure another. A certain homeopathic correlation can be seen in the use of the mole cricket to cure epilepsy: convulsions are a typical symptom both in case of tetanus and epilepsy. Serbians used to heal epilepsy with the mole cricket as well: to that end a mole cricket would be killed on an immovable stone, then put into water and the water was given for a child to drink (Gura, 2004, p. 211).

A healing hand

In ethno-medicine the mole cricket is used both as internally and externally. A special magic procedure was practiced in Lithuania which required killing that insect by one’s bare hand in order to gain healing powers. The mole cricket had to be killed by the back of the hand, i.e. not by the palm (LTR cd 188/02). Sometimes special conditions for the ritual were needed: the mole cricket had to be killed by the right hand and at one blow (LTR 374d/1984‑52). Or, it was required to kill three times nine (three times nine, i.e. twenty seven) insects by the back of one’s hand (LTR 725/213).

Killing of a mole cricket by the back of the hand is similar to other magic healing rituals, for instance, when curing scarlet fever, the patient’s clothing was put into an old shoe, carried to the end of the village and then thrown away backwards (moving one’s arm back) [Lietuvių užkalbėjimai, p. 296]. When curing swollen joints, one needs to tie the sore spot by a string of a broom and then to put the broom into its place moving one’s arm backwards (Lietuvių užkalbėjimų šaltiniai, p. 1289). Doing something backwards or by the back of one’s hand means an outward action, away from oneself and is intended as helping to get rid of a disease or some other thing. For example, a yarn is thrown backwards so that one’s warts went away (Lietuvių užkalbėjimai, p. 403). When bringing in harvest from the fields, stones are thrown backwards to corners of a barn so that mice ate the stones and not the grain (Lietuvių užkalbėjimų šaltiniai, p. 1618). A similar significance is attributed to a piece of clothing worn wrong side out: it is said that if you wear your shirt wrong side out, witches will not trick you (LKŽe: išvirkščias). Thus, killing of a mole cricket by the back of one’s hand is a certain subduing of the insect and at the same time enhancing of the action by turning it into a magic procedure.

Various goals may be sought by killing the mole cricket. For instance, it is believed that the person slapping a mole cricket by the back of his/her hand, will not be harmed by its bite (LTR 610/92) or that the one who kills a mole cricket will never suffer from the pain in the arm (LTR cd 187/02).

However, the main aim of killing the mole cricket is to acquire a special healing power. The person who kills a mole cricket gains an ability to heal by the touch of his/her hands. It is usually believed that such hand can cure horses as it is enough to stroke a horse when it has a stomachache and the animal will be cured (LTR cd 191/7).

The mole cricket is not the only creature suitable for gaining special healing powers. The mole is used in a very similar manner. They say that when you catch a mole, you should place it on your palm and wait until it dies, then your hand will be a healing one (Elisonas, 1932, p. 196, 198). It is believed that if a mole’s blood trickles on someone’s hands, he/she will be able to heal any swollen person (Elisonas, 1932, p. 198).

Both in the case of the mole cricket and the mole the following moments are important: an animal must be killed by the hand for the latter to become ‘helping’, i.e. to gain certain healing powers.

Why are these animals chosen in particular?

The mole cricket and the mole have two common features: first, they both live in the ground and dig tunnels where they nest and breed. Second, one common detail of their appearance is important: both the mole and the mole cricket shovel tunnels by their forelimbs which are well developed and remind a human hand. The front paws of the mole have more similarity to human hands than any other creature’s limbs; the front tarsus of the mole cricket looks like small shovels but fingerlike protrusions may be discerned. The similarity between a human hand and forelimbs of those animals determine the belief that a mole and a mole cricket killed by the hand make that hand a healing one.

The power of hands is very significant in the Lithuanian ethno-medicine. For instance, in terms of the cured disease or the pain which is gone they say that “it was taken away as if by the hand”: kaip ranka nuėmė (LKŽe: ranka). An enchanter or a charmer is described as “having nine hands”: devynias rankas turi (LKŽe: ranka) which means that he/she is a highly-qualified healer. The number nine (or seven) are not random either, it occur in other areas of healing, e.g. in curing by medicinal plants. They say that St John’s wort cures nine or ninety-nine diseases; mullein (Verbascum) is called devynjėgė which means “having nine powers” (LKŽe). As for differences between the cat and the dog it is noticed that “a cat’s tongue has seven poisons and a dog’s tongue has seven cures” (LTR 52/2).

Since nine hands signify a special healing qualification, the magical killing of a mole cricket or a mole can be interpreted as gaining or taking over of mythical powers of their ‘hands’.

The mole cricket and good luck

The mythical role of the mole cricket is associated both with a context of ethno-medicine and a concept of success. According to one informant when a person sees a mole cricket, he/she should think of a wish before the mole cricket manages to think. Then the wish comes true provided the mole cricket is killed by the back of the hand (LTR cd 193/9). In another case there was a story about a woman who performed the following ritual for her flax to grow well and be suitable for weaving sashes: she saw a mole cricket and killed it by the back of her hand. Then she waited for the full moon, put on a white linen shirt and went to sow flax at night and was sowing flax-seed by the hand that killed the mole cricket (LTR 7043/89).

In both these cases the same magic procedure is applied as in gaining healing powers: the mole cricket must be killed by the back of one’s hand, etc. Yet in these cases we should talk about the hand which brings luck and not the healing hand. In Lithuanian a person who is successful is described as having a special hand which is called gera ranka “a good hand”, laiminga ranka “a lucky hand”, lengva ranka “an easy hand” (LKŽe: ranka). The one who has such hand has a gift of luck: whatever he/she sows, it germinates and grows, if he/she plants a tree, it takes root, if he/she puts a hen to brood, chickens hatch from all eggs (LKŽe: ranka), etc. And on the contrary, a saying sunki ranka “a heavy hand” is used referring to a person who fails at everything he/she does.

About a person who is successful in everything he/she does they say [jam] į ranką eina “[something—crop, animals, etc.] comes to [his/her] hand”. And when someone fails, he/she is described as [jam] išeina iš rankos “he or she loses [something] from [his] hand”, i.e. the person incurs losses (LKŽe: ranka). Obviously, a potential lot of wealth (animals, harvest, hay, etc.) is meant which is figuratively “attracted” to the person and his/her lucky hand (as if the person’s hands could attract success). The labor done by the lucky hand goes well, the plants touched by it flourish, fruit trees bear fruit, animals do not get sick, wounds heal, etc.

It should also be emphasized that success is not everlasting: it can be gained as well as lost. According to the Lithuanian Dictionary the hand may be impaired: the expression pagadinti ranką “to impair the hand” is very common in Lithuanian. It means that a person can lose his luck because it is “taken over” by someone else. Good luck can be returned back however; in this case people say: ranką pataisyti “to mend the hand”, LKŽe: ranka). Knowing that the luck may change, one naturally tries to attract it by all means possible. One of such methods of attracting luck to one’s hands is the magic operation with the mole cricket. When a mole cricket is killed by the back of one’s hand, its power to materialize its wishes is being transformed and passes on to the person who may implement his/her wishes despite their subject, be it healing, crop, animals, etc. This is how thinking of the mole cricket and the power of its thoughts which is enhanced by its impressive “hands” are being transformed into the power of human thoughts and wishes that come true. The latter power is in fact revealed by the magic efficiency of the healing hand or the lucky hand.

Figure 3. – “Hand” of the mole.

Photo by Nova [Agnieszka Kwiecień], 2005 (Wikimedia).

Figure 4. – “Hand” of the mole cricket.

Photo by Jiří Berkovec, 2005 (Wikimedia).