Introduction

This article examines the translation of contemporary Chinese works in the humanities and social sciences into English between 1989 and 2019. It explores the intellectual, political, geopolitical, economic, and social factors shaping these translations and their circulation. As both a site of knowledge production and a sociopolitical entity, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, China) provides a compelling case for analysing the complex dynamics behind translation flows. The historical transformations of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have unfolded intensely in China, offering a privileged vantage point for observing how translations interact with shifting global power structures and knowledge hierarchies.

This article argues that analysing translation flows from a specific sociopolitical constituency over time offers a more complex understanding of evolving translation dynamics. It also underscores the persistent tension between national and transnational forces in the circulation of translations, despite recent trends in scholarship that de-emphasize the role of the nation-state dimension.

The analysis is based on a bibliographical dataset of 256 Chinese works in the humanities and social sciences1 translated into English between 1989 and 2019. The complete dataset can be consulted in Pavón-Belizón (2025), and it was compiled according to the following criteria: it includes book-length volumes2 originally written in Chinese and translated into English, authored by individuals who have been active in mainland China since at least 1980. The corpus covers translations published between 1989 and 2019 by English-language publishers based outside the People’s Republic of China. Data collection was conducted through bibliographic searches in a combination of complementary sources, following Poupaud et al. (2009), including UNESCO’s Index Translationum, the catalogues of the British Library and the U.S. Library of Congress, publishers’ catalogues, and online bookstores such as Amazon (UK and US) and Abebooks. Each entry was manually recorded with information on year of publication, author, title, translator, editor (where applicable), paratexts (including their authorship), publisher, series or collection (if relevant), and any funding institution involved. Bibliographic and translational data were obtained primarily from peritextual materials, such as the cover, credit page, acknowledgements, and prefaces or introductions. Titles were excluded from the dataset if it could not be confirmed that they were translations rather than originally written in English.

Compiling this dataset involved navigating significant complexity due to the dispersed nature of the sources and the multiplicity of variables required for each entry. The process demanded careful cross-referencing across various catalogues, publishers, and online platforms, as well as close attention to peritextual materials to verify translation status and gather contextual metadata. Additionally, the reliance on online sources may introduce geographical biases, as the visibility and availability of titles can vary significantly depending on regional publishing practices and digital accessibility. Despite these limitations, I believe the resulting dataset offers a valuable empirical foundation for analysing translation flows, revealing patterns and shifts that would remain obscured without such a systematic, albeit unavoidably limited, approach.

The analysis takes a sociohistorical approach as suggested by Sapiro et al. (2020, pp. 2–3), which combines attention to the contextualization of translations with the sociological aspects of translation and circulation processes, such as the implicated agencies and their interests, as well as the material conditions surrounding them. I will pay attention to the intellectual, political, economic, or social contexts that surrounded these publications, together with the references to such contexts that may appear, either inscribed in the translated text itself or in paratextual elements. When possible, personal communications with authors, editors and translators provide valuable insights into the intricacies of translation projects that may not be reflected in published paratexts, especially in the case of more recent translations. While not used extensively in this article, I refer to two such communications (with one editor/translator and one author) that provided pertinent details for specific aspects of the analysis.

This article also seeks to contribute to the growing connectivity between translation studies and global intellectual history. Moyn and Sartori (2013, pp. 14–15) highlighted the role of translation as a central mediating activity in the global flow of ideas and the importance of interconnected and multidirectional exchanges. These dynamics are particularly evident in the case of Chinese translations, as the analysis will show.

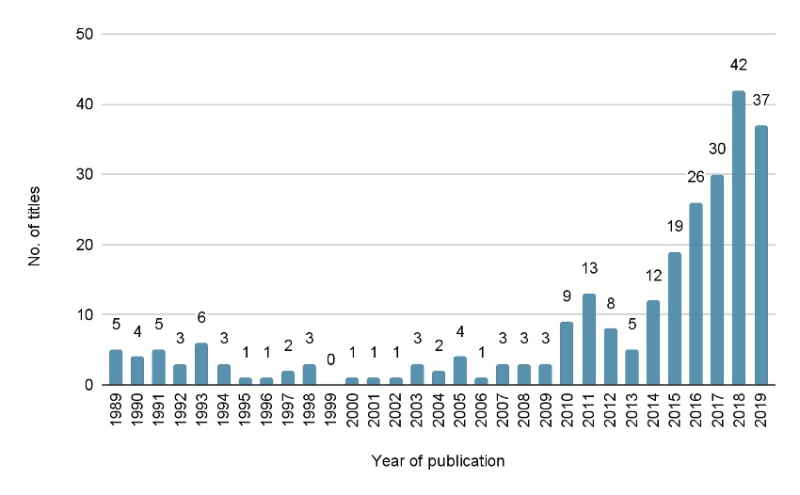

The compiled data (see Figure 1) illustrates certain translation trends. Between 1989 and 2009, only fifty-five titles have been identified (an average of 2.6 titles per year). This number increases markedly for the period ranging from 2010 to 2019, with 201 (an average of 20.1 per year). Notably, the data found for the last five years of the decade show 154 titles, averaging 30.8 titles annually.

Figure 1: Number of Chinese titles in the humanities and social sciences translated and published in English (1989–2019).

Considering the content and paratextual elements along with the intellectual, political, geopolitical, economic, and social contexts of translations during those years, I suggest three different phases characterized by specific dynamics:

Phase one (the early 1990s) is marked by the 1989 Tiananmen protests and their aftermath. This phase includes works by individuals associated with the movement, often labelled as “dissidents”. On the other hand, it also features works dealing with socioeconomic issues. These titles use “modernization theory” as a frame of reference, reflecting the resurgence of this paradigm in post-Cold War discourse, with its prescriptive stances on social and economic development in China.

Phase two (the early 2000s) includes several anthologies and essay collections by Chinese scholars and intellectuals. These translations coincide with China’s growing integration into the global economy. They seek to offer insights into China’s internal development and to bridge a perceived knowledge gap about China by introducing key thinkers and debates.

Phase three (the 2010s) is characterized by a sharp increase in both the volume and nature of translation. Unlike earlier periods dominated by target-context publishers, many recent translations are driven by Chinese initiatives, often with official financial support, reflecting China’s growing geopolitical role. Moreover, these initiatives no longer cater to the interests of the target context but align instead with China’s official agendas and strategic priorities.

The following sections will examine each of these three phases, analysing their specific contexts and the dynamics at play. It is important to emphasize that the identification of these phases is based on observable trends in the data I have gathered and the dynamics inferred from their paratextual materials. As previously noted, there are potential limitations stemming from uneven data availability. Consequently, this analysis should not be seen as a definitive or exhaustive characterization, as other important underlying logics and dynamics may exist within each phase that were not apparent in the paratextual sources. This limitation is particularly evident in the third phase, where my analysis is mostly focused on (geo)political and economic factors. The intensity and higher volume of publications (201) in that phase would require a more specific analysis to fully capture other existing dynamics.3 Finally, I must emphasize that, while these phases follow a chronological order, the discourse and dynamics of one phase are not entirely supplanted by the next. Rather, they accumulate and overlap.

Dissidents and modernization theory in the early 1990s

Translations published in the early 1990s reveal two main topics: political dissent, mostly in relation to the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, and economic development and reforms. To get an idea of the relevance of these two topics, among the thirty-three translations of humanities and social sciences from Chinese into English between 1989 and 1999, ten were related to the first topic and thirteen to the latter, making up more than two thirds of the publications during that decade.

The Tiananmen protests and its suppression caused an increased interest in China’s sociopolitical predicaments, prompting some commentators to observe that “[t]he struggle for democracy in China is in fashion” (Owen, 1990, p. 29). These events placed political repression at the centre of European and North American perceptions of China, reinforcing an enduring imaginary of “China as dystopia” (Lee, 2015) and leading publishers to a sustained preference for Chinese works marked by political controversy or censorship (Edwards, 2013, pp. 272–275). Vukovich (2012, p. 34) has noted how this interpretation tends to portray Chinese people as devoid of political and intellectual agency. This interpretation aligns with broader culturalist claims that suggest an inherent absence of rational and critical discourse in China, thereby calling into question the very existence of a post-Mao public sphere.4

Taken to centre stage of world events, China scholars in the US played an important role in the promotion and dissemination of these translations. As I will show, well-known names in the field of Chinese studies, such as Timothy Brook, Orville Schell, Jonathan D. Spence, Perry Link, or Merle Goldman, often appear as the authors of prologues, introductions or reviews in the press, as well as translators in some cases.

Translations in the very early 1990s gave prominence to “dissident” authors that had been related to the protests. One such author was Liu Binyan (1925–2005), a prominent journalist for People’s Daily, renowned for his investigative articles exposing corruption and injustice. A long-time member of the Communist Party of China (CPC), Liu was expelled twice, first in 1957 and again in 1987. That same year, he left China for the United States, where he later held academic positions at Harvard and Princeton. Liu’s writings had already been introduced to English-language audiences as early as 1983. In 1989, he published another collection of his writings linked to the recent events in China: “Tell the world”: What happened in China and why (Liu, 1989). The following year, another translation of his work was released, China’s crisis, China’s hope (Liu, 1990). The texts included in those collections were written in exile but originally in Chinese. The promotional blurb of the latter publication reflects the heightened tension between authoritarianism and democratization underscoring perceptions of China at that time:

The principal force in awakening the people and setting them on the road to struggle, Liu Binyan argues, has been the repeated mistakes of the Chinese Communist Party and the outrageous bureaucratic corruption it has allowed to flourish. Even as he describes the runaway inflation that inflicts unfathomable hardship on all but the elite party officials, the increasing isolation and hypocrisy of the Communist leadership, or the political persecution of intellectuals and the press, Liu’s message is one of hope. This book—written in one man’s eloquent voice—is testimony to his belief that the need for democratic reform has taken root among the Chinese people and that they will ultimately take steps to transform their nation. (Back cover of Liu, 1990)

An examination of the reviews of these works reveals the discursive frameworks within which they were received. A review of Liu’s latter book, published in Foreign Affairs, reflects a prevailing sense of optimism regarding China’s impending democratization, emphasizing that “[t]he authors predict that increasing social crises and popular opposition will enable the more moderate forces within the party to replace the hardliners in the government” (Zagoria, 1990). Similarly, Gregor Benton’s (1991) dual review of Liu’s aforementioned books in The China Quarterly begins by highlighting Liu’s background as a dissenting voice within the CPC before comparing his views on China’s democratic prospects with those of Fang Lizhi (1936-2012), another prominent intellectual who had recently gone into exile. While Benton tempers expectations of immediate democratization, the inevitability of such a political transformation remains a central assumption in his analysis:

For Fang Lizhi, the prospects for change in China are now grim: democracy will take at least 20 to 30 years to be achieved. Liu Binyan’s perspective on the other hand, is far more optimistic and short-term. And whereas Fang looks for change to the elite, Liu sees it brewing among the workers and peasants, whom he knows well from his long years of banishment to the villages; he predicts that a “genuine popular force” will emerge soon from China's discontents. (Benton, 1991, p. 853.)

Fang was an internationally renowned astrophysicist who emerged as a prominent social critic in the late 1980s, openly advocating for liberal political reforms. As a key intellectual figure in the movements leading up to the 1989 protests, Fang sought political asylum in the United States in 1989. In 1990, he published Bringing down the Great Wall: Writings on science, culture, and democracy in China in English. This volume, a collection of essays, interviews, and speeches written between 1979 and 1990, opens with an introduction by China scholar Orville Schell, who contextualized Fang’s scientific and intellectual trajectory while emphasizing his long-standing critique of authority dating back to the Hundred Flowers Movement in 1957. Additionally, in an introduction to one of the book’s sections, editor James H. Williams likens Fang to Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov and Czech playwright and politician Václav Havel (Fang, 1990, p. 88), situating him within the broader canon of counter-communist intellectuals of the era.

Reviews of the book similarly emphasized Fang’s dissident identity and his political confrontations with the Chinese state. For instance, historian Jonathan D. Spence (1991), writing in The New York Times, published an editorial pointedly titled “A man of unspeakable truths,” in which he introduces Fang as “one of China's best-known dissidents” and recalls Fang’s forced escape into the US embassy in Beijing after being accused by the Chinese Government of being one of the instigators of the 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen Square. In addition, Fang was also very vocal about his opposition to communism. In one of his most famous speeches in China, translated and included in this collection, he states:

[...] socialism is in trouble everywhere. Since the end of World War II, socialist countries have by and large not been successful. [...] And the socialist system in China over the last thirty-odd years has been exactly that, a failure. This is the reality we face. No one says it, or at least not outright, but in terms of its actual accomplishments, orthodox socialism from Marx and Lenin to Stalin and Mao Zedong has been a failure. (Fang, 1990, pp. 159–160)

Another publication in a similar vein is Yan Jiaqi and China's struggle for democracy, a collection of essays and interviews with Yan Jiaqi (b. 1942), a political scientist recognized in China for co-authoring, with his wife Gao Gao, a controversial history of the Cultural Revolution—an account that would later be translated and published in English (Yan & Gao, 1996). Having worked primarily within the CPC, Yan grew increasingly critical of the system and went into exile in 1989. While abroad, he became the first president of the newly established Front for a Democratic China. In the introduction to the book, the editors compare Yan to other dissident figures familiar to English-speaking audiences. At the same time, they expose the extent to which Chinese dissidents had become a publishing phenomenon and how they were related to specific topics of interest:

Yan Jiaqi is less well known to Westerners than are such dissident/opposition figures as Fang Lizhi, Liu Binyan, and Su Shaozhi. Partly this is because Fang, Liu, and Su were forced to become outsiders earlier than was Yan. Partly this is because the latter figures have had more of their work translated into English. Fang Lizhi’s blunt outspokenness captured the interest of foreign reporters and academics. The literary quality and poignancy of the works of Liu Binyan and Wang Ruoshui, another prominent dissident, which forced readers in China and the West alike to confront the nature of communist rule on several levels, attracted much attention. Even Su Shaozhi, whose role in the political system and the reform process most nearly resembles Yan Jiaqi’s, was much better known than Yan because of Su’s ambitious attempt to redefine Marxism (reformist Marxism with Chinese characteristics) in order to provide the basis for reform in China. (Yan, 1991, introduction by Bachman & Yang, pp. xiii–xiv)

Interpretations of the June 1989 protests were linked to the dominant social, political, and economic discourse of the time, namely the reappraisal of modernization theory or its evolved avatar, ‘globalization’. The crisis and dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s were seen as proof of the fragility of socialist alternatives and the inevitable triumph of the US-led liberal order, which seemed to position liberal democracy and free-market economy as the only viable models for social development. As Gilman (2007) observes, “during the first world economic boom of the late 1990s, there were many who discussed globalization breathlessly as the triumph of the market and democratization, with capitalism delivering all things to all people as efficiently as possible” (p. 260). These ideological shifts had a direct impact on the selection of Chinese works for translation and publication in the Anglophone world, embedding critiques of socialist governance and autocratic rule within both the content of the works and their reception.

For instance, Fang’s arguments aligned closely with these intellectual and political currents, offering an insider perspective that reinforced the core tenets of modernization theory—namely, that China’s progress depended on the adoption of Anglo-American political models. Fang articulated his vision for China’s development with clarity, advocating a hierarchical and evolutionary framework of cultural development:

I personally agree with the “complete Westernizers.” What their so-called “complete Westernization” means to me is complete openness, the removal of restrictions in every sphere. We need to acknowledge that when looked at in its entirety, our culture lags far behind that of the world’s most advanced societies, not in any one specific aspect but across the board. (Fang, 1990, p. 158)

Since the late 1970s, China had initiated a program of economic reforms that appeared to align with those prospects. After the temporary setback of the Tiananmen protests, the commitment to economic reform was reinforced in 1992 with Deng Xiaoping’s renowned “southern tour.” Lucien Pye (1990), a key observer of China’s political landscape at the time, argued that a “great transformation” was occurring globally, noting that “developments as economic growth, the spread of science and technology, the acceleration and spread of communications, and the establishment of educational systems would all contribute to political change” potentially more significantly than what was foreseen by modernization theory in the 1950s and 1960s (p. 7). Given the centrality of economic issues during this period, it is unsurprising that more than one-third (13 out of 33) of the Chinese works translated and published between 1989 and 1999 were focused on China’s economy.

However, the suppression of the Tiananmen protests also fostered a degree of scepticism regarding the prospects of reform movements in authoritarian regimes. In response, Pye (1990) argued that “our understanding of the likely outcome of the various crises of authoritarianism calls for a breakthrough in theory building so that we can better understand the problems of the interrelationship of the universal world culture and the particularistic national cultures” (pp. 12–13). This critique of earlier modernization and democratization paradigms, along with a reassessment of the cultural factors at play, is evident in Goodman’s review of Yan Jiaqi’s aforementioned book. In this review, Goodman (1991) describes Yan as “[o]ne of the few Chinese voices who has been prepared to argue for a radically different politics based on openness and accountability throughout the 1980s” (p. 852). However, he cautions:

[...] this is still not to suggest that Yan has embraced western ideas of democracy. On the contrary, his interpretation of that concept owes perhaps more to a Chinese emphasis on social harmony and he appears to have little understanding of democracy as process, and particularly of conflict resolution. (Goodman, 1991, p. 852)

Another related area of inquiry during this period was the question of the influence of cultural factors on development, although these factors were understood in more nuanced and less essentialist terms than in previous decades. By the 1970s, a more empirical approach began to challenge the “national character” paradigm, which had previously been used in comparative social sciences to explain divergent development paths across different regions of the world. Scholars such as Almond (1994, pp. vii–viii) critiqued this paradigm for its propensity toward psychological reductionism. Despite these more nuanced approaches, the alleged role of cultural differences in shaping development paths in Asia, and specifically in China, continued to be reassessed by several scholars in the late 1980s and 1990s. Notably, scholars like Pye (1985) revisited Weber’s famous thesis on Confucianism, arguing that China’s Confucian traditions served as a productive force, facilitating distinct forms of modernization in East Asia—an idea that would later be conceptualized as “Confucian modernity.”

Closely linked to the focus on the cultural foundations of social development, an important translation of this time was From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society (1992), a classic of Chinese sociology by Fei Xiaotong (1910–2005). This work, originally written in 1947, continued to exert considerable influence within China’s sociological community. In their foreword, the editors and translators articulate their motivations for undertaking the translation, linking it to both their personal research interests and the broader intellectual debates in Chinese Studies at the time. They argue that the book

may be even better suited to today's climate of opinion than to the earlier one [when the book was originally published], because Fei addresses the structural foundations of social pluralism and cultural diversity. By describing the fundamental differences between Chinese and Western societies, Fei helps us to understand the distinctiveness of Chinese society and to look at Western modernity in a new way.

We decided to translate this book because we were engaged in a similar pursuit. We, too, were contrasting China and the West in order to understand the distinctiveness of Chinese society. (Hamilton & Wang, 1992a, p. vii)

Later in their introduction, the translators further emphasize that “Fei’s sociology of Chinese society runs directly counter to a Chinese Marxist interpretation of Chinese society. It offers a very different view of the society and recommends a very different course of action for facing China’s economic and social problems” (Hamilton & Wang, 1992b, p. 4). This statement directly engages with another key concept in comparative social and political sciences that was undergoing increased reappraisal at the time: the “Asiatic mode of production” (AMP), a concept famously discussed by Marx, and the related theory of “Oriental despotism,” which had been a central focus for Marxist scholars such as Wittfogel (1957). Earlier modernization theorists had viewed the AMP and “Oriental despotism” as structural features that could help explain contemporary authoritarian rule in Asia. However, by the 1970s, scholars began to question the utility of the AMP as an explanatory framework for understanding modern social, economic, and political developments in the region (Jones, 2001, pp. 168–169). As part of this reassessment, Timothy Brook’s 1990 publication, The Asiatic mode of production in China, emerged as a critical contribution to the debate. This volume, a collection of translated essays by Chinese scholars, was intended as an intervention in that debate:

[t]he Chinese voices in the debate on the AMP have largely gone unheard in the West, although some of the writings of their Soviet and European counterparts have been made available in English. Since China is one of the candidates for ‘Asiatic’ society, it behooves us to bring Chinese perspectives on the AMP into the debate. (Brook, 1990, p. 3)

The analysis of the English translations of Chinese works in the late 1980s and early 1990s shows that they were primarily shaped by the interests and discussions surrounding China within Anglophone contexts, with Modernization serving as the dominant metadiscourse. Despite the surge in interest regarding China’s society and history during this period, the number of works by contemporary Chinese scholars translated into English during the late 1980s and early 1990s remained limited in comparison to the volume of research on China produced by European and North American scholars, as noted by Brook in the previous quotation. This discrepancy likely reflects challenges such as limited access to source texts and underdeveloped socio-intellectual networks at the time between scholars in China and abroad. However, as I will examine in the next section, translation initiatives in subsequent years sought to address these limitations.

Cartographies of China’s intellectual field in the 2000s

Beginning in the early 2000s, as China’s rising status in the global arena became increasingly evident, the scarcity of knowledge about this emerging power in Europe and North America became strikingly apparent. After decades of relative mainstream indifference, China’s rapid ascent as a global economic powerhouse appeared, to many, to have occurred unexpectedly. This shift prompted widespread interest, from policymakers to the general public, in understanding the trajectory that had led to China’s transformation. In this context, there was also a growing demand for knowledge about Chinese intellectual discourse, seen as essential for grasping the ideological foundations of the country’s rise and anticipating its future direction. In response, a range of institutions and actors began working to address this knowledge gap, particularly in the fields of social and political sciences, but also more broadly within the humanities.

Translation played a crucial role in making the works of Chinese scholars and intellectuals accessible to Anglophone audiences, and it did so in a very specific form: translation anthologies and collections. As Chan (2015, p. 47) observes, compilations of translated texts, arranged according to more or less concrete criteria, serve as an effective means when there is a need to introduce several authors in a short period of time to provide an informative picture in order to fill a knowledge void in the reception context. Similarly, Seruya et al. (2013) underscore the production of translation anthologies and collections as relevant practices in “the creation, development and circulation of national and international canons, and the process of canonization of texts, authors, genres, disciplines and sometimes even concepts” (p. 4).

As I mentioned in the previous section, Brook’s 1990 edited book on the AMP was an early example of this type of publication. Since the turn of the century, there has been an intermittent release of translated essay collections by Chinese intellectuals: Voicing concerns (Davies, 2001); One China, many paths (Wang, 2003), and Voices from the Chinese century (Cheek et al., 2019).

Unlike Brook’s single-topic volume, the anthologies edited by Davies and Wang were among the earliest attempts to provide a comprehensive overview of contemporary China’s intellectual landscape. Both collections function as “survey anthologies,” designed to serve as “representative repositories” of authors and trends (Seruya et al., 2013, p. 5). As translation initiatives, these anthologies adopt a distinctly documentary approach, presenting their contents as contextual information about internal debates among Chinese intellectuals about China’s own development. This approach is visible in the editors’ lengthy introductions, which help contextualize the essays.

Davies’ (2001) volume declares a linguistic and rhetorical focus, presenting the “differences between Chinese and Western modes of critical inquiry” (p. 2). Chinese intellectuals are characterized by seeking knowledge that offers solutions to specific problems in China, and by their positivistic usage of language, unlike Anglophone intellectuals’ “self-reflexive problematizing of language and thought” and their “existentialist or ontological tenor” (Davies, pp. 4, 7). The function of this collection as a documentary survey is also clear from the selection of essays translated, all of them dealing with problems related to China’s intellectual history, the conditions of Chinese intelligentsia and China’s modern history. This linguistic and rhetorical focus keeps the editor away from making overall demarcations of political or ideological trends. In a review of this collection, Karl (2003, p. 184) noted that this anthology was explicitly conceived in contrast to other contemporary anthologizing initiatives (i.e., Zhang, 2001, which I will address below), that Davies considered as forcibly aligning Chinese intellectual debates with the theoretical concerns of contemporary Western thought (Davies, 2001, p. 2).

The goal of Wang’s (2003) anthology was similarly “to give English-speaking readers a sense of how many original and forceful minds now find expression in China” (p. 40). While also panoramic, Wang’s anthology does however manifest a political underpinning and, although also addressing the conditions of intellectual life in China, her volume is most concerned with social, economic, and political issues. In this sense, it is important to note that this book was published by Verso, the imprint of The New Left Review (NLR), including essays that had previously appeared on the pages of the review. Notwithstanding these ideological premises, Wang’s book is not exclusively consecrated to kindred Chinese left-wing thinkers. In her introduction, she posits the then-recent “liberal vs. new left” divide as the range upon which intellectuals are positioned in her anthology with numerical balance—five for the new left, five for the liberals, and three non-aligned (Wang, 2003, p. 40).

The year 2001 saw the publication of another volume, Whither China?, edited by Xudong Zhang, then a Professor of Comparative Literature and East Asian studies at New York University. This book was a collection essays on recent Chinese intellectual politics that were, most of them, first published in English as a special issue of the journal Social Text in 1998. However, only three out of its eleven essays were translated from the Chinese (which is why this volume is not included in the database). Notwithstanding this, it is worthy of comment, first because it was contrasted to other contemporary anthologizing initiatives and, second, because it heralded a change in how the works of Chinese intellectuals were introduced to Anglophone readers: Zhang’s edited volume was conceived not as an overview of China’s intellectual landscape but as an intellectual intervention from China on a transnational political debate at the time. In his preface, Zhang (2001, p. viii) points to the increasing integration of China within global capitalism and the encounter of its intellectuals with concrete sociopolitical issues that were common in the globalizing market economies. His intention in the selection of authors and essays was therefore to contradict the assumed idea that the development of a market economy and globalization were not being debated nor encountering any notable opposition in China (Xudong Zhang, personal communication, July 11, 2016). This programmatic principle presides over the selection of the translated authors and essays included in the volume, all of them recognizable for their critiques of neoliberalism.

Zhang’s collection was revealing of a new situation in Chinese intellectual production that has grown increasingly evident: that Chinese intellectuals could no longer be regarded as isolated, but were increasingly enmeshed in transnational intellectual dynamics. This idea is especially prominent in the most recent anthology by Cheek et al. (2019). The outline of the volume is based on the already common tripartite division of China’s intellectual sphere between liberals, new leftists, and new Confucians. But unlike previous anthologies, the editors explain that the selection of texts to be translated is the product of surveys among Chinese scholars “to find out which texts they feel are important”, thus reflecting “our commitment to Chinese voices over our North American concerns of preferences” (Cheek et al., p. 2). Besides, the editors position Chinese intellectuals as seeking to understand China’s new role in the world, but also as active participants in global discussions, challenging the notion that their contributions are isolated from broader international debates on modernity, democracy, and development.

In fields such as public policy, governance, and international relations, China’s rise as a global power became an urgent topic of scholarly inquiry, particularly following the global financial crisis of 2008, after which China’s growing status on the world stage was widely recognized. During that period, China studies in the academia and publishing industry experienced a notable growth. For instance, China studies programs expanded across North American universities, often bolstered by funding from Chinese institutions as well as domestic support reflecting a somewhat cautious belief in the promise of China’s global integration and the growing academic interest in understanding China as a major international actor (Shambaugh, 2013).

In that context, a number of translation initiatives emerged during this period, focusing on issues related to policy and governance, geopolitics, diplomacy, and international relations. Notably, many of these translation projects were supported by institutions and think tanks dedicated to research and analysis in the areas of international politics, global governance, and policy development.

A prominent example of this trend is the John L. Thornton China Center, affiliated with the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. In 2009, this centre launched the Thornton Center Chinese Thinkers Series, which offered English translations of works by selected Chinese intellectuals. Four volumes of this series are listed in the dataset. The series was edited by Cheng Li, the Director of Research at the China Center, as well as a director at the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations. In one of its prefaces, the editor emphasized the need for such translations, arguing that “English-language studies of present-day China have not adequately informed a Western audience of the dynamism of the debates within China and the diversity of views concerning its own future” (Hu, 2011, introduction by Li, p. xvi). The interests underlying this translation and publishing initiative are clearly stated in the series’ presentation:

The John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings develops timely, independent analysis and policy recommendations to help U.S. and Chinese leaders address key long-standing challenges, both in terms of Sino-U.S. relations and China’s internal development. As part of this effort, the Thornton Center Chinese Thinkers Series aims to shed light on the ongoing scholarly and policy debates in China.

China’s momentous socioeconomic transformation has not taken place in an intellectual vacuum. Chinese scholars have actively engaged in fervent discussions about the country’s future trajectory and its ever-growing integration with the world. This series introduces some of the most influential recent works by prominent thinkers from the People’s Republic of China to English language readers. Each volume, translated from the original Chinese, contains writings by a leading scholar in a particular academic field (for example, political science, economics, law, or sociology). This series offers a much-needed intellectual forum promoting international dialogue on various issues that confront China and the world. (“Series’ Presentation” in Yu, 2009, p. ii).

This policy-oriented approach is salient in the choice of authors and texts to be included in the collection. All the selected authors are scholars working near official organs or at top-level institutions in mainland China (Peking University and Tsinghua University) in fields related to governance, public policy, and law, and in some cases had close contact as advisors to policymakers and even top-level officials. Moreover, they are all conversant with the ideas of the European and North American tradition of political thought, with most of them having spent considerable time at foreign academic institutions. The case of Yu Keping is probably the most eloquent example of the kind of authors and ideas sought after by the Thornton series. At the time of publication of his essays, Yu Keping kept a double profile as scholar and guest professor at several Chinese institutions, and official as the deputy director of the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau, an organ with ministerial rank and one of the main bodies of theoretical production for China’s officialdom (Yu, preface by Li, 2009, pp. xxii–xxiii). Similarly, referring to another translated author, Hu Angang, the series stresses his importance based on the “measurable impact” of his ideas upon Chinese decision-makers:

[N]o scholar in the PRC has been more visionary in forecasting China’s ascent to superpower status, more articulate in addressing the daunting demographic challenges that the country faces, or more prolific in proposing policy initiatives designed to advance an innovative and sustainable economic development strategy than Hu Angang. (Hu, 2011, foreword by Thornton, p. xvi)

As evidenced by the examples discussed above, translations since the turn of the twenty-first century have been defined by China’s rise to the forefront of global politics, prompting a realization among European and North American observers of the significant knowledge gap regarding this emerging global power. Translation initiatives during this period shared a common goal: to bridge this gap and offer deeper insights into the key figures—policymakers, intellectuals, and advisors—shaping China’s development trajectory. Anthologies, in particular, have been serving as an efficient means of providing an overview of China’s intellectual landscape since the early 2000s, paving the way for more specialized, single-authored translations in the coming years.

From “translated modernity” to “translating (Chinese) modernity” in the 2010s

For the last decade (2010-2019), the dataset shows a sharp increase in the number of translations. Besides this quantitative increase, there is an unprecedented shift with regard to the agencies behind these publishing initiatives: if in previous decades the translation of Chinese works in the humanities and social sciences was mostly driven by the intellectual, social and political dynamics and interests of the target contexts, in this decade there is a growing number of translations published by international English-language publishers, yet initiated and funded by agents from within China, including official organizations and academic institutions, and responding to source-context interests and agendas. Among the 201 published translations identified between 2010 and 2019, a total of eighty-three volumes (41.3 percent) acknowledge funding from different Chinese institutions. This wave of “outbound translation” (Chang, 2017) is part of a government-led “going-out strategy” (走出去策略) that aims at placing China’s cultural production on par with its economic might, a goal that is related to China’s increasing concern in recent years about soft power and cultural international projection (Edney et al., 2020; Yang & Ocón, 2023; Tian, 2024).

The Chinese government has been very vocal about the importance it attaches to the global dissemination of its cultural products, including China’s production in the humanities and social sciences, as part of a “comprehensive national power” (综合国力) (Zhang, 2010). In March 2004, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China published a document titled “Suggestions with regard to the further burgeoning development of Philosophy and Social Sciences” pointing to the development of these disciplines and the international dissemination of its fruits as a matter of national strategic interest (Zhongguo Gongchandang Zhongyang Weiyuanhui, 2004). In that direction, outbound translation began to appear explicitly as a key part of the overall strategy. A 2011 document issued by the CPC’s Central Committee emphasized the necessity of organizing the translation of academic and cultural products into foreign languages (Zhongguo Gongchandang Zhongyang Weiyuanhui, 2011, section 7).

The idea that the strength of a nation’s cultural (including academic) production is an important part of the nation’s overall strength has been upheld by successive leaderships under Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. For instance, in October 2023, a National Conference on Propaganda, Ideology and Culture called for the enhancement of the country’s cultural soft power and the influence of Chinese culture (Xinhua News Agency, 2023). Subsequently, organizations such as the Translators Association of China have set out to enhance “national translation capabilities” as a response to Xi’s call to “tell the story of Chinese modernization well” (讲好中国式现代化的故事), that is, to promote the country’s own official narrative about its social development through translation (Du, 2024).

This endeavour has materialized through different programs aimed at promoting and funding the translation and publication of works by Chinese intellectuals and scholars abroad. As Sapiro (2008) observes, “as the international market of translation becomes free and global, some state representatives begin to act as literary agents promoting national authors to be translated by publishers in the target country” (p. 163). This is particularly crucial for academic works, which belong to the “restricted pole of production”—a category in which translation costs are high while commercial returns remain relatively low (Sapiro, 2019). These translation initiatives underscore the increasing ability of actors within China to actively shape translation agendas abroad and advance their strategic interests in global intellectual and cultural exchanges. This growing influence is facilitated by China's expanding financial resources and strengthened international position, which have made foreign publishers and other cultural institutions more receptive to collaboration with Chinese organizations. Among the institutional funding programs acknowledged in published translations, we find national programs such as the Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences and the China Book International (supported by the General Administration of Press and Publication and the Information Office of the State Council), China Classics International Program, as well as programs by academic institutions such as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Innovation Translation Fund, Fudan University Press, the Confucius Institute at Stanford University, the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Shanghai Translation Grant and Tsinghua University’s Humanities Publication Fund. Finally, some funding initiatives are led by publishing houses such as the Shanghai Century Literature Publishing Company and Shanghai Culture Development Foundation.

The Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences (the official English rendition of 国家社会科学基金, hereafter CFHSS) is currently the main funding program for academic activities. The CFHSS supports translations through its Chinese Academic Translation Program (中华学术外译项目), established in 2010 to fund the translation of academic works by Chinese scholars into foreign languages. Though the program is open to funding translations toward different languages, English is the most common target language (Tan, 2022, pp. 338–339). The direct political and ideological priorities of the program are clear in the main areas for funding translation defined in its call for applications 2024-2025, in which the program states as its main topics for funding those related to the promotion of the Chinese state’s official ideology and its modernization model:

Topics should focus on the latest research and interpretation of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, which helps the international community understand the sinicization and modernization of Marxism; research on the important achievements and historical changes in contemporary China’s economic construction, political construction, rule of law construction, cultural construction, social construction, ecological civilization construction, etc. (National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences, 2024)

Other topics listed later point to works on China’s traditional civilization and its moral concepts, as well as the translation of Chinese-developed theories and academic paradigms, which is a key part of China’s push for a discursive self-reliance and the construction of a knowledge system of its own, independent of prevailing Euro-American paradigms.

The outlook of China’s recent outbound translation initiatives offers a sharp contrast from what we have observed in the 1990s, when the post-Cold War reappraisal of modernization theory had the conviction that China would move closer to European and North American forms of social organization. As noted by Mahoney (2014),

[u]ntil the early 2000s, Chinese academic discourse was being driven substantially by its attempts to assimilate and debate Western liberal and leftist positions, and struggling to do so under the Party’s gaze. [...] Today there is a growing belief that such alternatives are perhaps more distant, if not difficult to find. After 1999, 9/11, Iraq, the global Financial Crisis and the US’s pivot towards China, Western—particularly American—liberalism no longer enjoys the same cachet it once had, even among Chinese liberals. (p. 61)

Chinese scholars are increasingly engaged in formulating their own analytical categories and in developing models that are positioned as parallel to, rather than subordinate to, those of European and North American academia. For Chinese officialdom, this trend provides an opportunity to assert intellectual legitimacy for alternative approaches to governance, and there is a concerted effort to disseminate these perspectives internationally. In a certain way, if in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries we could speak of a “translated modernity” (Liu, 1995) in which Chinese intellectuals introduced different elements of European modernity into their context, now we could speak of Chinese intellectuals’ efforts in “translating (Chinese) modernity”, in the sense that there are attempts at building alternative self-reliant forms of knowledge and to exhibit and disseminate them abroad.

Besides, the surge of outbound translation and the political/nationalistic underpinnings of some of its initiatives have also influenced the very understanding of translation as a practice and as an academic discipline in China. As Xu (2024) notes, there is “an overt concern to take on the task of translating the nation to the world, an explicit aspiration to ‘tell China’s stories well’ both as an objective of practice and as concern of theory” that overemphasizes the usual adherence to notions of “textual self-containment and uniqueness of cultural expression” in Chinese translation thought (p. 125).

Despite increasing resources, these initiatives have met with some problems and limitations. A fundamental one is the risk that these initiatives end up catering to the interests of the source context, rather than seeking to engage the intellectual and scholarly fields in the reception contexts. Chang (2017) noted that the going-out strategy may be an instrument to “enhance the auto-image of (official) Chinese culture rather than to improve the position of Chinese culture in the polysystem of the world” (pp. 599–600). In his analysis of similar outbound translation initiatives emanating from the Arab world, Jamoussi (2015) warned that

projects that integrate all agents within the export circuit [source context] are doomed to failure. The recipient culture matrix cannot accommodate projects that are carried out externally and only export projects which establish solid links with import [target context] agents have a chance to succeed (p. 183).

Another problem regarding the reception of these translated works is their frequent placement within the framework of China-focused collections rather than within their respective homologous disciplinary fields. Among the 201 titles registered in our dataset between 2010 and 2019, 152 titles (75.6 percent) were included in China-themed series. This tendency is even more salient among translations sponsored by Chinese initiatives, where, among the eighty-three titles that received Chinese institutional funding, seventy-six (91.6 percent) were published within such collections. This pattern suggests a persistent classification of Chinese scholarship under the umbrella of area studies rather than integrating these works into their corresponding academic disciplines. In some cases, this may occur even when their content is not inherently China-specific. For instance, Wang Min’an’s monograph Lun jiayong dianqi (论家用电器, On electric household appliances), a work originally conceived as a theoretical discussion without geographic specificity, was ultimately published in English translation under the title Domestic spaces in Post-Mao China: On electric household appliances, effectively repositioning the work within a Chinese Studies framework (Wang Min’an, personal communication, September 14, 2016). Thus, while the increase in outbound translation has had a clear quantitative impact on translation flows, it remains to be seen whether this shift will lead to qualitative changes in the disciplinary reception of Chinese scholarship in the humanities and social sciences in English.

Finally, Chinese scholars have also noted limitations in the publication, distribution, and availability of these works abroad. In 2019, Ma Yumei noted that, among the 356 translation projects approved between 2010 and 2015, only fifty-eight were ultimately published. Moreover, they were often issued by Chinese publishers without international distribution (Ma, 2019, pp. 66–67). To address these limitations, in more recent years, Chinese publishers and institutions have entered into collaboration agreements with foreign publishing outlets such as Springer, Routledge, Brill, and Cambridge University Press. These agreements cover translation costs and other expenses (Zhang, 2014). However, the unfolding of such agreements has raised concerns with regard to censorship. For instance, the journal Frontiers of Literary Studies in China, published by Brill in partnership with China Higher Education Press, was found to have edited or rejected content on political grounds, ultimately leading Brill to terminate the partnership (Redden, 2019).

As previously shown, while the translation of Chinese humanities and social sciences into English after 1989 was largely shaped by the dynamics of the reception context, the expansion of China’s outbound translation initiatives since the 2010s has reversed that outset. This shift appears to challenge Toury’s (1995, p. 29) well-known assertion that translations are fundamentally facts of the target culture. In the analysis of the last decade of our dataset, Chinese institutions in the source context have appeared as the primary drivers of translation efforts, boasting their own interests and political agendas.

The Chinese case is also eloquent about how transnational dynamics coexist in tension with dynamics that insist in the reinforcement of national frameworks (Jong, 2023). In the first two phases, it was observable how the translation of Chinese humanities and social sciences into English responded to transnational dynamics, such as the intellectual or political discussions developing in the target context in the midst of geopolitical transformations. Then, the third phase has shown how Chinese state and national concerns are able to shape translation dynamics. Despite predictions of its declining influence, the nation-state remains a resilient entity in the twenty-first century. So, we conclude with Baer (2020, p. 466), that, rather than completely discarding the nation from translation dynamics, a self-critical perspective is necessary for translation to serve as a means of interrogating the nation-state rather than uncritically reinforcing the exclusions it causes.

Conclusions

This article has presented a diachronic analysis of translations of Chinese humanities and social sciences into English between 1989 and 2019 with attention to the social, political, and intellectual context in which translations were undertaken and published, alongside the different agencies involved. As observed, this kind of analysis provides a deeper understanding of how knowledge is produced, legitimized, and disseminated across boundaries. By examining translation dynamics aggregated in three different phases of works, this article has shown the diverse and changing nature of intellectual, political, geopolitical, economic, and social dynamics involved in translation. As noted earlier, while the identified phases reflect trends observed in the data and paratextual materials, limitations in data availability mean that other underlying logics and dynamics may be at play, requiring more a more targeted and in-depth analysis.

This analysis is intended to contribute to the positioning of translation within global intellectual history by highlighting the role of translation in the transnational movement of ideas and in the creation of interconnections between different intellectual contexts. It has also highlighted the importance of mediating agencies such as publishers, academic institutions, and governmental initiatives, as well as individual translators, in shaping the transnational flow of ideas. These aspects are especially salient in this study case: as the analysis showed, the translation of Chinese works is multidirectional in the sense that different processes of translation can be related to dynamics at work in various locations which often break away from well-defined binary ideas of source and target contexts. More precisely, the common idea that translation is a fact of the target context appears as problematic in this case, as many translations into English respond to source-context initiatives. The observations from this case call for a multilayered, interconnected, and multidirectional understanding of translation as an active and reciprocal process, shaped by local and transnational forces, and further emphasizes the need to reconsider the role that translation has played and can continue to play in shaping the global intellectual landscape.